Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

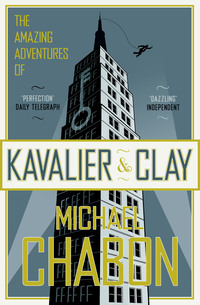

Kitabı oku: «The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay», sayfa 11

“Stop wasting your life,” were the stranger’s last words. “You have the key.”

Max spent the next ten years in a fruitless search for the lock that the golden key would open. He consulted with the master locksmiths and ironmongers of the world. He buried himself in the lore of jailbreaks and fakirs, of sailor’s knots and Arapaho bondage rituals. He scrutinized the works of Joseph Bramah, the greatest locksmith who ever lived. He sought out the advice of the rope-slipping spiritualists who pioneered the escape-artist trade and even studied, for a time, with Houdini himself. In the process, Max Mayflower became a master of self-liberation, but the search was a costly one. He ran through his father’s fortune and, in the end, still had no idea how to use the gift that the stranger had given him. Still he pressed on, sustained without realizing it by the mystic powers of the key. At last, however, his poverty compelled him to seek work. He went into show business, breaking locks for money, and Misterioso was born.

It was while traveling through Canada in a two-bit sideshow that he had first met Professor Alois Berg. The professor lived, at the time, in a cage lined with offal, chained to the bars, in rags, gnawing on bones. He was pustulous and stank. He snarled at the paying public, children in particular, and on the side of his cage, in big red letters, was painted the come-on SEE THE OGRE! Like everyone else in the show, Max avoided the Ogre, despising him as the lowest of the freaks, until one fateful night when his insomnia was eased by an unexpected strain of Mendelssohn that came wafting across the soft Manitoba summer night. Max went in search of the source of the music and was led, to his astonishment, to the miserable iron wagon at the back of the fairgrounds. In the moonlight he read three short words: SEE THE OGRE! It was then that Max, who had never before in all this time considered the matter, realized that all men, no matter what their estate, were in possession of shining immortal souls. He determined then and there to purchase the Ogre’s freedom from the owner of the sideshow, and did so with the sole valuable possession he retained.

“The key,” Tom says. “The golden key.”

Max Mayflower nods. “I struck the irons from his leg myself.”

“Thank you,” the Ogre says now, in the room under the stage of the Palace, his cheeks wet with tears.

“You’ve repaid your debt many times, old friend,” Max Mayflower tells him, patting the great horny hand. Then he resumes his story. “As I pulled the iron cuff from his poor, inflamed ankle, a man stepped out of the shadows. Between the wagons,” he says, his breath growing short now. “He was dressed in a white suit, and at first I thought it must be him. The same fellow. Even though I knew. That he was where. I’m about to go myself.”

The man explained to Max that he had, at last and without meaning to, found the lock that could be opened by the little key of gold. He explained a number of things. He said that both he and the man who had saved Max from the kidnappers belonged to an ancient and secret society of men known as the League of the Golden Key. Such men roamed the world acting, always anonymously, to procure the freedom of others, whether physical or metaphysical, emotional or economic. In this work they were tirelessly checked by agents of the Iron Chain, whose goals were opposite and sinister. It was operatives of the Iron Chain who had kidnapped Max years before.

“And tonight,” Tom says.

“Yes, my boy. And tonight it was them again. They have grown strong. Their old dream of ruling an entire nation has come to pass.”

“Germany.”

Max nods weakly and closes his eyes. The others gather close now, somber, heads bowed, to hear the rest of the tale.

The man, Max says, gave him a second golden key, and then, before returning to the shadows, charged him and the Ogre to carry on the work of liberation.

“And so we have done, have we not?” Max says.

Big Al nods, and, looking around at the sorrowing faces of the company, Tom realizes that each of them is here because he was liberated by Misterioso the Great. Omar was once the slave of a sultan in Africa; Miss Plum Blossom had toiled for years in the teeming dark sweatshops of Macao.

“What about me?” he says, almost to himself. But the old man opens his eyes.

“We found you in an orphanage in Central Europe. That was a cruel place. I only regret that at the time I could save so few of you.” He coughs, and his spittle is flecked with blood. “I’m sorry,” he says. “I meant to tell you all this. On your twenty-first birthday. But now. I charge you as I was charged. Don’t waste your life. Don’t allow your body’s weakness to be a weakness of your spirit. Repay your debt of freedom. You have the key.”

These are the Master’s last words. Omar closes his eyes. Tom buries his face in his hands and weeps for a while, and when he looks up again he sees them all looking at him.

He calls Big Al, Omar, and Miss Blossom to gather around him, then raises the key high in the air and swears a sacred oath to devote himself to secretly fighting the evil forces of the Iron Chain, in Germany or wherever they raise their ugly heads, and to working for the liberation of all who toil in chains—as the Escapist. The sound of their raised voices carries up through the complicated antique ductwork of the grand old theater, rising and echoing through the pipes until it emerges through a grate in the sidewalk, where it can be heard clearly by a couple of young men who are walking past, their collars raised against the cold October night, dreaming their elaborate dream, wishing their wish, teasing their golem into life.

9

THEY HAD BEEN WALKING for hours, in and out of the streetlights, through intermittent rainfall, heedless, smoking and talking until their throats were sore. At last they seemed to run out of things to say and turned wordlessly for home, carrying the idea between them, walking along the trembling hem of reality that separated New York City from Empire City. It was late; they were hungry and tired and had smoked their last cigarette.

“What?” Sammy said. “What are you thinking?”

“I wish he was real,” said Joe, suddenly ashamed of himself. Here he was, free in a way that his family could only dream of, and what was he doing with his freedom? Walking around talking and making up a lot of nonsense about someone who could liberate no one and nothing but smudgy black marks on a piece of cheap paper. What was the point of it? Of what use was walking and talking and smoking cigarettes?

“I bet,” Sammy said. He put his hand on Joe’s shoulder. “Joe, I bet you do.”

They were at the corner of Sixth Avenue and Thirty-fourth Street, in a boisterous cloud of light and people, and Sammy said to hold on a minute. Joe stood there, hands in his pockets, helplessly ordering his thoughts with shameful felicity into the rows and columns of little boxes with which he planned to round out the first adventure of the Escapist: Tom Mayflower donning his late master’s midnight-blue mask and costume, his chest hastily emblazoned by the skilled needle of Miss Plum Blossom with a snappy gold-key emblem. Tom tracking the Nazi spy back to his lair. A full page of rousing fisticuffs, then, after bullet-dodging, head-knocking, and collapsing beams, an explosion: the nest of Iron Chain vipers wiped out. And the last panel: the company gathered at the grave of Misterioso, Tom leaning again on the crutch that will provide him with his disguise. And the ghostly face of the old man beaming down at them from the heavens.

“I got cigarettes.” Sammy pulled several handfuls of cigarette packages from a brown paper bag. “I got gum.” He held up several packs of Black Jack. “Do you like gum?”

Joe smiled. “I feel I must learn to.”

“Yeah, you’re in America now. We chew a lot of gum here.”

“What are those?” Joe pointed to the newspaper he saw tucked under Sammy’s arm.

Sammy looked serious.

“I just want to say something,” he said. “And that is, we are going to kill with this. I mean, that’s a good thing, kill. I can’t explain how I know. It’s just—it’s like a feeling I’ve had all my life, but I don’t know, when you showed up … I just knew.…” He shrugged and looked away. “Never mind. All I’m trying to say is, we are going to sell a million copies of this thing and make a pile of money, and you are going to be able to take that pile of money and pay what you need to pay to get your mother and father and brother and grandfather out of there and over here, where they will be safe. I—that’s a promise. I’m sure of it, Joe.”

Joe felt his heart swell with the longing to believe his cousin. He wiped at his eyes with the scratchy sleeve of the tweed jacket his mother had bought for him at the English Shop on the Graben.

“All right,” he said.

“And in that sense, see, he really will be real. The Escapist. He will be doing what we’re saying he can do.”

“All right,” Joe said. “Ja ja, I believe you.” It made him impatient to be consoled, as if words of comfort lent greater credence to his fears. “We will kill.”

“That’s what I’m saying.”

“What are those papers?”

Sammy winked and handed over a copy each of the issues for Friday, October 27, 1939, of the New Yorker Staats-Zeitung und Herold and of a Czech-language daily called New Yorske Listy.

“I thought maybe you’d find something in these,” he said.

“Thank you,” Joe said, moved, regretting the way he had snapped at Sam. “And, well, thank you for what you just said.”

“That’s nothing,” said Sammy. “Wait till you hear my idea for the cover.”

10

THE ACTUAL CURRENT OCCUPANTS of Palooka Studios, Jerry Glovsky, Marty Gold, and Davy O’Dowd, came home around ten, with half a roast chicken, a bottle of red wine, a bottle of seltzer, a carton of Pall Malls, and Frank Pantaleone. They walked in the front door boisterously quibbling, one of them imitating a muted trumpet; then they fell silent. They fell so quickly and completely silent, in fact, that one would have said they had been expecting intruders. Still, they were surprised to find, when they came upstairs, that Palooka Studios had been transformed, in a matter of hours, into the creative nerve center of Empire Comics. Jerry smacked Julie on the ear three times.

“What are you doing? Who said you could come in here? What is this shit?” He pushed Julie’s head to one side and picked up the piece of board on which Julie had been penciling page two of the adventure he and Sammy had cooked up for Julie’s own proud creation, a chilling tale of that Stalker of the Dark Places, that Foe of Evilness himself,

“The Black Hat,” said Jerry.

“I don’t remember saying you could use my table. Or my ink.” Marty Gold came over and snatched away the bottle of India ink into which Joe was about to dip his brush, then dragged his entire spattered taboret out of their reach, scattering a number of pens and pencils onto the rug, and completely discomposing himself. Marty was easily discomposed. He was dark, pudgy, sweated a lot, and was, Sammy had always thought, kind of a priss. But he could fake Caniff better than anyone, especially the way he handled blacks, throwing in slashes, patches, entire continents of black, far more freely than Sammy would ever have dared, and always signing his work with an extra-big letter O in Gold. “Or my brushes, for that matter.”

He snatched at the brush in Joe’s hand. A pea of ink fell onto the page Joe was inking, spoiling ten minutes’ work on the fearsome devices arrayed backstage at the Empire Palace Theatre. Joe looked at Marty. He smiled. He drew the brush back out of Marty’s reach, then presented it to him with a flourish. At the same time, he passed his other hand slowly across the hand that was holding the brush. The brush disappeared. Joe brandished his empty palms, looking surprised.

“How did you get in here?” Jerry said.

“Your girlfriend let us in,” Sammy said. “Rosa.”

“Rosa? Aw, she’s not my girlfriend.” It was stated not defensively but as a matter of fact. Jerry had been sixteen when Sammy first met him, and had already been dating three girls at a time. Such bounty was then still something of a novelty for him, and he had talked about them incessantly. Rosalyn, Dorothy, and Yetta: Sammy could still remember their names. The novelty had long since worn off; three was a dry spell now for Jerry. He was tall, with vulpine good looks, and wore his kinky, brilliantined hair combed into romantic swirls. He cultivated a reputation, without a great deal of encouragement from his friends, for having a fine sense of humor, to which he attributed, unconvincingly in Sammy’s view, his incontestable success with women. He had a “bigfoot” comedy drawing style swiped, in about equal portions, from Segar and McManus, and Sammy wasn’t entirely sure how well he’d do with straight adventure.

“If she’s not your girlfriend,” said Julie, “then why was she in your bed naked?”

“Shut up, Julie,” Sammy said.

“You saw her in my bed naked?”

“Alas, no,” said Sammy.

“I was just kidding,” said Julie.

Joe said, “Do I smell chicken?”

“These are not bad,” said Davy O’Dowd. He had close-cropped red hair and tiny green eyes, and was built like a jockey. He was from Hell’s Kitchen, and had lost part of an ear in a fight when he was twelve; that was about all Sammy knew about him. The sight of the pink nubbin of his left ear always made Sammy a little sick, but Davy was proud of it. Lifting the sheet of tracing paper that covered each page, he stood perusing the five pages of “The Legend of the Golden Key” that Sammy and Joe had already completed. As he looked each page over, he passed it to Frank Pantaleone, who grunted. Davy said, “It’s like a Superman-type thing.”

“It’s better than Superman.” Sammy got down off his stool and went over to help them admire his work.

“Who inked this?” said Frank, tall, stooped, from Bensonhurst, sad-jowled, and already, though not yet twenty-two, losing his hair. In spite of, or perhaps in concert with, his hangdog appearance, he was a gifted draftsman who had won a citywide art prize in his senior year at Music and Art and had taken classes at Pratt. There were good teachers at Pratt, professional painters and illustrators, serious craftsmen; Frank thought about art, and of himself as an artist, the way Joe did. From time to time he got a job as a set painter on Broadway; his father was a big man in the stagehands’ union. He had worked up an adventure strip of his own, The Travels of Marco Polo, a Sunday-only panel on which he lavished rich, Fosterian detail, and King Features was said to be interested. “Was it you?” he asked Joe. “This is good work. You did the pencils, too, didn’t you? Klayman couldn’t do this.”

“I laid it out,” Sammy said. “Joe didn’t even know what a comic book was until this morning.” Sammy pretended to be insulted, but he was so proud of Joe that, at this word of praise from Frank Pantaleone, he felt a little giddy.

“Joe Kavalier,” said Joe, offering Frank his hand.

“My cousin. He just got in from Japan.”

“Yeah? Well what did he do with my brush? That’s a one-dollar red sable Windsor and Newton,” said Marty. “Milton Caniff gave me that brush.”

“So you have always claimed,” said Frank. He studied the remaining pages, chewing on his puffy lower lip, his eyes cold and lively with more than mere professional interest. You could see he was thinking that, given a chance, he could do better. Sammy couldn’t believe his luck. Yesterday his dream of publishing comic books had been merely that: a dream even less credible than the usual run of his imaginings. Today he had a pair of costumed heroes and a staff that might soon include a talent like Frank Pantaleone. “This is really not bad at all, Klayman.”

“The Black … Hat,” Jerry said again. He shook his head. “What is he, crime-fighter by night, haberdasher by day?”

“He’s a wealthy playboy,” said Joe gravely.

“Go draw your bunny,” Julie said. “I’m getting paid seven-fifty a page. Isn’t that right, Sam?”

“Absolutely.”

“Seven-fifty!” Marty said. With mock servility, he scooted the taboret back toward Sammy and Joe and replaced the bottle of ink at Joe’s elbow. “Please, Joe-san, use my ink.”

“Who’s paying that kind of money?” Jerry wanted to know. “Not Donenfeld. He wouldn’t hire you.”

“Donenfeld is going to be begging me to work for him,” said Sammy, uncertain who Donenfeld was. He went on to explain the marvelous opportunity that awaited them all if only they chose to seize it. “Now, let’s see.” Sammy adopted his most serious expression, licked the point of a pencil, and scratched some quick calculations on a scrap of paper. “Plus the Black Hat and the Escapist, I need—thirty-six, forty-eight—three more twelve-page stories. That’ll make sixty pages, plus the inside covers, plus the way I understand it we have to have two pages of just plain words.” So that their products might qualify as magazines, and therefore be mailed second-class, comic book publishers made sure to toss in the minimum two pages of pure text required by postal law—usually in the form of a featherweight short story, written in sawdust prose. “Sixty-four. But, okay, here’s the thing. Every character has to wear a mask. That’s the gimmick. This comic book is going to be called Masked Man. That means no Chinamen, no private eyes, no two-fisted old sea dogs.”

“All masks,” said Marty. “Good gimmick.”

“Empire, huh?” said Frank. “Frankly—”

“Frankly—frankly—frankly—frankly—frankly,” they all chimed in. Frank said “frankly” a lot. They liked to call his attention to it.

“—I’m a little surprised,” he continued, unruffled. “I’m surprised Jack Ashkenazy is paying seven-fifty a page. Are you sure that’s what he said?”

“Sure, I’m sure. Plus, oh, yeah, how could I forget. We’re putting Adolf Hitler on the cover. That’s the other gimmick. And Joe here,” he said, nodding at his cousin but looking at Frank, “is going to draw that one all by himself.”

“I?” said Joe. “You want me to draw Hitler on the cover of the magazine?”

“Getting punched in the jaw, Joe.” Sammy threw a big, slow punch at Marty Gold, stopping an inch shy of his chin. “Wham!”

“Let me see this,” said Jerry. He took a page from Frank and lifted the tracing-paper flap. “He looks just like Superman.”

“He does not.”

“Hitler. Your villain is going to be Adolf Hitler.” Jerry looked at Sammy, eyebrows lifted high, his amazement not entirely respectful.

“Just on the cover.”

“No way are they going to go for that.”

“Not Jack Ashkenazy,” Frank agreed.

“What’s so bad about Hitler?” said Davy. “Just kidding.”

“Maybe you ought to call it Racy Dictator,” said Marty.

“They’ll go for it! Get out of here,” Sammy cried, kicking them out of their own studio. “Give me those.” Sammy grabbed the pages away from Jerry, clutched them to his chest, and climbed back onto his stool. “Fine, listen, all of you, do me a favor, all right? You don’t want to be in on this, good, then stay out of it. It’s all the same to me.” He made a disdainful survey of the Rathole: John Garfield, living high in a big silk suit, taking a look around the cold-water flat where his goody-goody boyhood friend has ended up. “You probably already have more work than you can handle.”

Jerry turned to Marty. “He’s employing sarcasm.”

“I noticed that.”

“I’m not sure I could take being bossed around by this wiseass. I’ve been having problems with this wiseass for years.”

“I can see how you might.”

“If Tokyo Joe, here, will ink me,” said Frank Pantaleone, “I’m in.” Joe nodded his assent. “Then I’m in. Fra—To tell you the truth, I’ve been having a few ideas in this direction, anyway.”

“Will you lend one to me?” said Davy. Frank shrugged. “Then I’m in, too.”

“All right, all right,” said Jerry at last, waving his hands in surrender. “You already took over the whole damned Pit anyway.” He started back down the stairs. “I’ll make us some coffee.” He turned back and pointed a finger at Joe. “But stay away from my food. That’s my chicken.”

“And they can’t sleep here, either,” said Marty Gold.

“And you have to tell us how’s come if you’re from Japan, you could be Sammy’s cousin and look like such a Jew,” Davy O’Dowd said.

“We’re in Japan,” Sammy said. “We’re everywhere.”

“Jujitsu,” Joe reminded him.

“Good point,” said Davy O’Dowd.

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.