Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

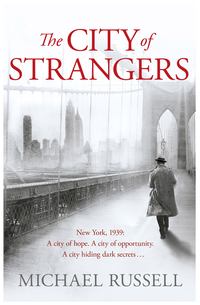

Kitabı oku: «The City of Strangers»

MICHAEL RUSSELL

The City of Strangers

For

Anya, Seren, Finn, Coinneach and Marta

And the Silver Meteor

To the Pennsylvania Station

Send but a song oversea for us,

Heart of their hearts who are free,

Heart of their singer to be for us

More than our singing can be.

‘To Walt Whitman in America’

Algernon Charles Swinburne

RPACN FEBSA HOGYH VTNOY IKSAO RYHOI VAUAR OAOIR OKWGQ MWAYA IERIL IETTM NNSTN ATAUA OIETH ARGTR YLHRA NASRI FOOAA AIALL TINYN LMENV NOOYG EEHOS OAOET GECTN: List of spies noted. Am forwarding it to Intelligence Director for his information. Are you able to carry out annihilation of all spies?

From Decoding the IRA

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

Part One: Uptown

1. Pallas Strand

2. Fulton Market

3. Kilranelagh

4. Corbawn Lane

5. Inns Quay

6. West Thirty-Sixth Street

7. The Yankee Clipper

8. Fifty-Second Street

9. Centre Street

10. Pennsylvania Six-Five-Thousand

11. Fifth Avenue

12. The Hampshire House

Part Two: Upstate

13. Locust Valley

14. Central Park

15. Flushing Meadows

16. A Hundred and Twenty-Fifth Street

17. The Waldorf-Astoria

18. Route Eleven

19. Mexico Bay

20. The Empire State

21. A Hundred and Sixteenth Street

22. Saint Patrick’s Cathedral

Part Three: Upstroke

23. Dún Laoghaire

24. Béarra

25. The Four Courts

26. Henrietta Street

27. Reilig Chill Rannaireach

28. Royal Oak

War and the Rumour of War

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Also by Michael Russell

Copyright

About the Publisher

PART ONE

Uptown

Mrs Leticia Harris, aged 53, who resided at 14 Herbert Place, Dublin, disappeared some time after 6 a.m. on Sunday, 8 th March. The following morning her car was discovered at premises in Corbawn Lane, leading from Shankill to the sea. There were numerous bloodstains inside the car, and the police later in the day found a bloodstained hatchet in a shed adjoining her house, and also bloodstains on the flower borders in the garden. The police theory is that Mrs Harris was murdered in her own home and the body taken away in her car. Mrs Harris is the wife of Dr Cecil Wingfield Harris, 81 Pembroke Road, Dublin.

The Irish Times

1. Pallas Strand

West Cork, November 1922

The storm did not come suddenly. All day the wind from the Atlantic had blown hard and cold and fast against Pallas Strand. The grey sky sped past overhead, heavy, thick, turbulent. The noise was unceasing, humming and roaring, loud and soft, and loud and soft again, but always there, along with the beat of the sea crashing endlessly against the white curve of sand. The farm lay back from the strand, behind a scattering of tufted dunes and a row of wasted trees, bent and twisted from long years of bowing and creaking before the wind, yet somehow always strong enough to stand. Indoors and out the blast of the wind battering the farmyard and the buildings had been constant, but still the rain hadn’t come.

The boy was in the yard, leaning into the wind to stand, scattering leftovers from a bucket to the ruffled and bad-tempered hens. He was seven; it had been his birthday only a week ago. He shouted and laughed as the puppy that had been his birthday present danced around him, darting and leaping, behind, in front, through his legs, trying to snatch the bacon rinds before the hens could get them. His father was in the barn, milking the three black cows. His mother was in the kitchen, peeling potatoes. He didn’t hear the two vehicles driving along the track from the main road. The wind was blowing the sound away from him. It was only as the dog turned sharply from the scraps and started to bark that he saw them.

He knew them well enough. The long, sleek Crossley Tourer came first, with its top open even in the wind, and its battered leather seats. He loved the Tourer and its white-walled tyres, despite the men inside it. The other one was different; a Rolls Royce armoured car with its squat turret on the back and its .303 Vickers machine gun sticking out through the letter-box sights. As the dog zigzagged angrily round the wheels of the Crossley, snapping and snarling, it stopped; three uniformed men got out. The boy knew them too. It wasn’t the first time they had driven into the farmyard at Pallas Strand.

There was a young lieutenant and two great-coated Free State soldiers. The lieutenant smiled; the boy didn’t smile back. No one got out of the armoured car; its turret moved in a slow, grating arc as the machine gun scanned the yard. The puppy kept up a furious yapping, now round the feet of the intruders, but a kick sent him flying across the muddy yard. The boy turned to find his father standing behind him. There was another man too, his uncle. Where his father was calm and steady, he could see the fear in the other man’s eyes. And his mother was there now, in the doorway of the house, wiping her hands dry with her apron. The lieutenant stepped towards the boy’s father.

‘You’ve heard what happened on the Kenmare road?’

‘I heard something.’

‘So where were you yesterday?’

‘I was here. Where else would I be?’

‘You were seen in Kenmare the day before, with Ted Sullivan.’

‘Who says?’

‘I do.’

The boy’s father shrugged.

‘There’s a Garda sergeant dead at Derrylough. A mine,’ said the officer.

The boy’s father shrugged again.

‘Someone said something about it.’

‘There was no mine on Tuesday. The road was clear.’

‘I wouldn’t know, Lieutenant. That’ll be your business.’

‘But Ted Sullivan would know, I’d say.’

‘That’ll be his business then. You’d need to ask him so.’

‘Maybe you’d know where he is then?’

‘Well, he wouldn’t always be easy to find.’

‘Unless you were an IRA man.’

‘There’d be a lot of IRA men in West Cork. You’d know yourself. And it’s not so long ago you fellers would have called yourselves IRA men.’

The boy’s father smiled. It was a mixture of amusement and contempt. It was a familiar conversation, empty, circular, quietly insolent; all the lieutenant’s questions would go unanswered. But he knew that. He turned to one of the soldiers and nodded. The man walked forward and slammed the butt of his rifle into the farmer’s stomach. As he collapsed to the ground the boy stepped between his father and the soldier, saying nothing, but glaring hatred and defiance. The soldier laughed. The boy’s mother ran forward across the yard, but her husband was already struggling to his feet. He looked at her sharply and shook his head. She stopped immediately. The boy turned to his father. The noise of the wind rose and blasted. The man smiled, despite his pain, and put his hand on his son’s head, ruffling his hair. The lieutenant put a cigarette in his mouth. He hunched over his hands for several seconds, trying to get his lighter to catch it. After a moment he straightened up, drawing on the smoke.

‘Let’s see what you’ve got to say at the barracks.’

The soldier who had knocked the boy’s father down took his arm and dragged him towards the Crossley Tourer. The other soldier covered him with his rifle. The turret of the armoured car creaked slowly as the machine gun swept round the farmyard once more. The boy watched as his father was pushed into the back seat of the car. Neither his mother nor his uncle moved. They had seen it before; it was always the same; the same questions and no answers. He would come back, beaten and bruised, but he would come back. The soldiers got into the car. Then the Crossley Tourer and the armoured car swept round in a circle in the farmyard, through the mud and the dung, and drove up the track towards the road to Castleberehaven, the dog chasing behind, still barking and snapping.

The woman walked forward. She took her son’s hand and smiled reassuringly. It would be all right. These were the things they lived with, that they had always lived with. Even at seven years old he was meant to understand that. The soldiers who had taken his father away were traitors; men who had sold the fight for Irish freedom for a half-arsed treaty with England that was barely freedom at all. Traitors were to be treated with contempt, not fear. Then his mother turned to his uncle, his face white, his fists clenched tight at his side. The fear was gone; now his face was full of anger.

The boy had once asked his mother why his father seemed to have no fear and his uncle, sometimes, had to hide his shaking hands. ‘A man can only give what he has,’ she told him. ‘If he gives it all, no one can ask more than that.’ She was very calm now. None of it was new to them. Three years ago it had been the English Black and Tans; now the men in uniform were Irish, but the same sort of shite. Rage was to be nurtured, as it had been for centuries. There would always be a time to use it.

‘You take the bike and go up to Horan’s. They’ll get a message to Brigadier Sullivan. He’d better know. And we’ll finish milking the cows.’

The boy’s uncle nodded and walked quickly away. The woman and the boy went into the barn. For a moment, as his mother put her arm round him and squeezed, the boy smiled again. He did know it would be all right.

They waited all that evening, wife and brother and son. The rain had finally come just before dark, beating in from the sea, and the wind began to drop. As night fell a more welcome car pulled into the farmyard. The IRA brigadier said the man was where they expected him to be, in the police barracks in Castleberehaven, on the other side of the peninsula. The Crossley Tourer had been seen driving in through the gates around four o’clock. The IRA had someone inside the barracks; when the man was released they’d have the information immediately. He would be collected and brought home. The Free Staters had pulled in a number of volunteers that afternoon; it was the usual game; most of the men were already home. They only had to wait.

When the boy went up to bed there was no sense of anxiety in the house. The rain was falling outside, but the storm was quiet. Lying in his bedroom under the eaves, listening to the rain rattling comfortably on the roof, he drifted off to sleep thinking of the days when he would hold a rifle in his hand and fight the fight his family fought now. But when he woke abruptly in the early hours of the morning, he knew something was wrong. The rain still fell, but the house wasn’t at its ease any more. He could hear voices downstairs; his mother’s, his uncle’s, and others, a woman, several men. He could make out no words, but the voices no longer echoed the assured tones of the brigadier. There was anxiety; he knew what that was. The voices grew louder and then someone said something to quieten them; but the quiet wasn’t really quiet; it was a series of harsh, adult whispers that only intensified the anxiety.

He got out of bed and crept across the room. He knew where each floorboard creaked; he stepped slowly and carefully. At the door he turned the knob and opened it just a crack. The lamps were still burning downstairs. He didn’t know the time, but he knew these were the early hours of the morning. The voices were still unclear. The broken words and overlapping phrases that came up the stairs wouldn’t fit together. ‘Five fucking hours ago – they drove him out, he was in the car – it was ten o’clock – no, the ones at Ardgroom were from Kenmare – Gerry Curran didn’t even pick up a gun – they pulled him out of bed – they already knew where the explosives was buried – so where is he?’

The voices stopped. People were moving downstairs. The door into the farmyard opened. The boy tiptoed to the window. He pulled back the curtain and looked down. Two men were walking across the farmyard. They carried rifles. His uncle followed, a few steps behind; he stopped and turned back to the house. His mother was there now, standing in the rain. His uncle stepped back. He put his arm round her and pulled her to him. It was the same gesture of reassurance the boy had received from his mother as they walked to the barn to milk the cows, but everything about the way his mother stood now, unmoving, unaware of the rain falling on her, said that she wasn’t reassured.

His uncle picked up the bicycle that lay on the ground by the door. He got on it and rode away. Ahead of him the two other men were on bicycles too, their rifles slung over their backs, their hats pulled down on their heads. The three of them rode out of the farmyard and within seconds the rain and the darkness had swallowed them. The light from the open door shone on his mother as she watched them go. The boy looked down from the bedroom window. It seemed a long time before she turned away from the darkness, back into the house. The door shut. She did not come upstairs.

He let the curtain fall back across the window. He stood in the dark room. He could hear no sound from the kitchen below, but somehow he knew that his mother was standing, just as he was, and that she was crying, just as he was. He could feel the tears now. He understood nothing, except that there were reasons for tears, and reasons to be afraid. He walked to his bed and knelt. He crossed himself and clasped his hands together, closing his eyes tightly. ‘Holy Mary, be a mother to me. May the Blessed Virgin Mary, St Joseph, and all the saints in heaven pray for us to the Lord, that we may be preserved this night from sin and evil. Good Angel, that God has appointed my guardian, watch over my Daddy and protect him from harm.’

The rain stopped very suddenly, just before dawn. The sun had been up for over an hour when the boy woke. He wasn’t in his bed. He was sprawled across it where he had finally fallen asleep in the middle of the prayers he had repeated over and over again. He got up and walked to the window to pull back the curtains.

The sun was low in the sky but the morning was clear and bright already. Outside he could hear the familiar sounds of the cows in the barn, waiting to be fed and milked. The cockerel called across the farmyard, loud and urgent. But the only other noise was the shrill sound of gulls, flocking overhead. It was a moment before the anxiety of the previous night pushed the morning aside, and he remembered.

He ran to the door and downstairs. There was no one in the kitchen. The door to the farmyard was open. The door to the sitting room was open too, but there was no one there. He ran back upstairs and burst into his mother and father’s bedroom. It was empty; the bed had not been slept in. He knocked on the door to his uncle’s room across the landing, then opened it; it was empty too and the bed was unused. He raced down the stairs again. He put his raincoat on over his pyjamas and pulled on his boots.

The farmyard was empty. He stood outside and looked around him. It was as if everyone he loved had simply disappeared; for a moment it was bewildering rather than frightening. But he knew the emptiness around him meant that the darkness of the night had not been swept away by the dawn. He looked at the sky. The noise of the gulls was very loud now. A great crowd of them rose and fell on currents of air over the sea beyond the dunes, tightly bunched, angry somehow.

He ran towards the sound, through the farmyard, past the haystacks, on to the track through the dune field, up on to the tussocky dunes. He stopped, looking out at Pallas Strand and the sea, and the crowd of people, away at the far end of the beach, where the gulls were flocking and diving and screeching overhead.

He ran towards the crowd; twenty-five, thirty people in a loose group. Some stood silently, looking towards the sea, away from something. Some stood with their heads bowed in prayer. Some were simply staring down at the sand. No one seemed to see him coming. As he reached the crowd and pushed through the onlookers, still none of them seemed to notice him.

His father’s head and shoulders rose out of the sand of Pallas Strand.

He had been buried up to his chest; his hands were by his side, somewhere beneath the sand. His head was facing out towards the sea. And where his eyes had been there were two pits of black and red pus.

The boy stared, not able to understand what he was looking at. It wasn’t real; it wasn’t a real thing at all. The first thing that came into his head was the face of the vampire he had seen at the cinema in Castleberehaven, when he had crept in at the back with Danny Mullins during Nosferatu a month ago; they had watched in open-mouthed awe, for all of five minutes, before they were yanked out by the ears. But he knew what he was looking at, of course he knew. And then it was gone. His uncle’s coat dropped over the head and covered it, and suddenly, as if a still photograph had sprung to life, everyone saw him.

His mother turned and came towards him. He didn’t see her; he was still staring down at the sand and the coat that covered his father’s head. She pulled him to her, standing between him and his father’s body, folding him in her arms before she pulled him away. He didn’t resist as she led him back towards the farm.

He didn’t even try to look back.

No one would let him look at his father’s face again. On the day of the removal, when the coffin rested all day in the farm’s best room and friends and neighbours walked from all around to drink tea and shake his hand, his mother’s hand, his uncle’s hand, the coffin would be shut. But in reality he would always see it; the black tears of blood on the wet cheeks. And as he walked silently along the strand with his mother now, the gulls were still screaming and baying for the feast they had been driven away from.

His father had died a hero. But life had to continue; there was a farm. Yet down the years of growing up in the farm behind Pallas Strand, he saw his father’s face whenever he heard the sound of hungry gulls. And though he had been told a thousand times that his father was already dead when the Free State soldiers buried him there, as a reprisal for the dead Free State sergeant at Derrylough, and as a brutal warning, he would still wake at night in terror, from dreams in which he couldn’t move his body, his legs, his arms, and he felt himself gazing helplessly at the waves moving towards him across Pallas Strand, where no one could hear his screams over the wind roaring in the darkness.

Grief would be softened as the years went by, but not rage. It was a secret strength. Rage had to be nurtured; there was a time to use it.

2. Fulton Market

New York, March 1939

In the Fulton Fish Market, below the Brooklyn Bridge on the Manhattan side of the East River, an Irishman was sitting at a coffee stall. He was a little over forty; tall, fair, with a little bit more weight than was entirely good for him. It was eleven o’clock in the evening and the place was gearing up for the night, as it did every night, its busiest time. It was as cold inside as it was outside. Lights shone fiercely over the stalls stretched out in every direction, but wind from the East River blew in through the open doors, and the crushed ice that was everywhere made it even colder. Fish was still arriving, in boxes and baskets, carried by porters and piled high on the forklift trucks that raced along the market aisles, blasting horns.

The air reeked of blood and the sea; the floor swam with melting ice and fish guts; the occasional live eel squirmed between the stalls, struggling for the doors and the smell of the East River beyond. The price of fish was shouted out with competing, overlapping cries that echoed endlessly round the building. The prices were called in English, but the profanities that accompanied them were in all the languages of New York: English, German, Yiddish, Italian, Greek, Chinese, Spanish, Polish, Russian, Armenian; like the varieties of fish, no one could count them all.

Captain John Cavendish, of the Irish army, Óglaigh na hÉireann, had been in New York for the last two months as an advisor on security during the construction of the Irish Pavilion at the World’s Fair, across the river in Long Island’s Flushing Meadows. He had also spent some of his time talking to the American army about weapons and training and munitions, and was compiling a report on all this to take back to Ireland. As far as both the ambassador in Washington and the consul general in New York were concerned, his previous role as an officer in Military Intelligence, G2, had nothing whatsoever to do with his presence in America. The fact that he was in New York at all, where the current IRA bombing campaign against Britain, now in full if ineffective swing, had been largely planned and financed, was no more than a coincidence.

It was a coincidence too that he was in New York while the IRA’s chief of staff was in America, selling not only the new war against the old enemy, but the idea that the bigger war that had to come, sooner or later, between Britain and Germany, would bring the IRA back to a position of power in Ireland itself. It would be a war that would chase England out of the corner of Ireland it still held on to; it would put an end to the toadying Free State that had found the temerity, under the leadership of the Republican turncoat Éamon de Valera, to almost call itself a ‘republic’; and it would reunite the island of Ireland.

Captain Cavendish perched on a stool at the coffee stall counter. He wore a dark grey lounge suit, a blue shirt, a silver tie, a navy blue overcoat and a pale grey fedora. He should have looked out of place among the porters and stallholders in Fulton Market, but nobody took any notice. The man he was chatting amiably to at the counter ought to have looked equally out of place, in a black cashmere overcoat and a black homburg, a half-smoked cigar clamped between his teeth. But men in overcoats and hats were no strangers to the market in the middle of the night; it was run by the Mob, after all, and the men in overcoats took a cut on every box of fish that came in and went out.

The man John Cavendish was talking to carried a .38 under his jacket, and he was important enough that the man in the brown homburg who had come into the market with him, and was now helping himself to boiled shrimps from the next stall, carried a .45 to make sure his boss had no need to use his .38. The man in the black homburg raised his hat to the captain and walked away, followed by his protection. He had a word for every stallholder he passed; the replies all contained the word ‘mister’.

John Cavendish looked at his watch; the man he was meeting was late. He had a good idea why and he didn’t much like it. But he had no choice but to wait. The army officer held out his empty coffee cup for a refill. And he liked the market. It was an old building that offered relief from the streets of towers and skyscrapers that stretched through Manhattan. It was a manageable place. It reminded him of the South City Markets in Dublin; it had the same red brick, the same arched windows, the same broken gabled lights in the roof, the same vaulting interior and battered, shabby, workaday appearance. Living in the future, as he had been told he was many times since arriving in New York, he liked to touch the past.

The man he was waiting for had docked at Pier 17 on the Hudson River two hours earlier. There were piers by Fulton Market too, but there were no grand Atlantic liners there, only the fishing boats from Long Island and New England, and the ferries to Brooklyn. Donal Redmond’s ship was the French Line’s SS Normandie; he was a steward. He would have picked up the message he was delivering, as he always did, when the boat stopped at Cobh on its way from Le Havre to New York. And before the delivery was made at the other end he would give it to John Cavendish to copy.

‘You’re late.’

‘I’m here, what else do you want?’

‘You’d be better off out of the White Horse every time you dock.’

‘If I didn’t have a few in there, they’d think something was up.’

‘You’ve had more than a few.’

‘I’ve been on that boat six fucking days. What do you care?’

‘I don’t,’ said Cavendish, getting up off the stool. ‘Have you got it?’

Donal Redmond nodded. He followed the army officer through the maze of stalls, out to the back of the market, where the boxes of fish were loading and unloading. Trucks and cars, horses and carts, barrows and forklifts were everywhere. Money was changing hands outside as it was in, and arguments were still going on about prices that had started at the stalls and carried on out to the street; hands were spat on and shaken; illegible dockets and receipts were scrawled out and dropped into the slush of ice and blood and litter.

John Cavendish sat with the steward in the front of his red and white Crossley. In all the noise and the constant movement of vehicles a man scribbling something down in the front of a car looked like any other wholesaler or restaurateur totting up his bill.

The two letters, on thin copy-paper flimsies, had been rolled up tightly into straws and buried in a tin of Jacob’s shortbread biscuits. On each of the two pages were several paragraphs of typed capital letters; the letters grouped in neat columns, each five letters wide, with a space between each group. Cavendish copied both pages, laying the letters out exactly as in the typed originals. He rolled up the pages as tightly as they had emerged from the tin, then twisted the top and bottom of each one. The other man pushed them back under the biscuits, pressed the lid down tightly, and turned to stuff the tin into the duffel bag that was now on the back seat of the captain’s car.

‘Do you want a lift over to Queens?’

‘OK. Suits me.’

John Cavendish took five ten dollar bills from his wallet and handed them over. The steward put them in his pocket and grinned. It was done.

‘Merci, mon brave. Quelque chose à boire?’

Cavendish reached under the dashboard and pulled out a silver and leather hip flask. As he started the engine he handed it to Donal Redmond. He drove from Front Street on to Fulton Street, past City Hall and up on to the Brooklyn Bridge, over the East River to Long Island. He drove through Brooklyn into Queens. Redmond said nothing now; their business was over. Two blocks from the call house in Woodside, at the corner of 58th Street and 37th Avenue, where the ciphers would be delivered, the army officer stopped the car. The steward got out, hauled his duffel bag from the back seat and walked away.

As he disappeared from sight Cavendish reached for the hip flask and drank the remaining whiskey; as he put his hands back on the steering wheel he realised they were shaking. He pulled out into the road. A horn blasted angrily. The Irishman smiled to himself and tutted, ‘Cavendish, Cavendish!’ He drove on. He’d said he’d meet her an hour ago. He was heading for La Guardia now, for the Triborough Bridge, and then Harlem.

It was one o’clock in the morning in Small’s Paradise on 7th Avenue and 135th. It was hot, however cold it was outside. The downtown whites with the appetite for it had left the restaurants and bars of Lower Manhattan to join the black crowds in Harlem now, where the music was always louder but more importantly always better, much better, and you could dance with a woman in ways that would have got you thrown out of the Rainbow Room for even thinking about. The mix of black and white customers was a natural thing in Small’s; it was natural enough that nobody thought very much about it; Ed Small was black after all. There were white-owned, Jim Crow Harlem clubs, like the Cotton Club, where only the waiters and the musicians were black. But there were black clubs and black clubs of course; Small’s Paradise was just about as black as Manhattan’s more adventurous white downtowners and midtowners could comfortably cope with.

John Cavendish was happy enough to be there for the music, which he had grown to love during his months in New York. He’d heard a lot of it now and he never tired of hearing more. It was like nothing he’d known, and whatever he’d heard before, on records or the radio, was only the palest reflection of what it felt like to be in a room with it. He was easy there; he would have been happy just to listen.

The Irish woman he was with, Kate O’Donnell, was maybe thirty, tall, with blue eyes that had the habit of always looking slightly puzzled. Her hair was cut just above her shoulders, blonde enough not to need bleaching, and with enough curl not to need perming; sometimes she even brushed it, but not so often that it looked brushed. She was dressed well, but if you’d asked her what she had on, she would have had to check. She wasn’t easy sitting there. There was an edge of anxiety about her. She needed one of the trumpeters in the band with her when she talked to John Cavendish tonight.

If the captain was going to help her, she wanted him to help her now. She had started to feel he was putting it on the long finger. They needed to talk harder again; the captain, her, the trumpeter; they needed to move.