Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

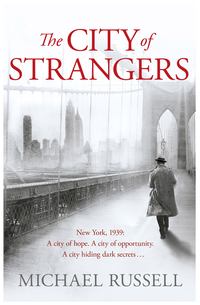

Kitabı oku: «The City of Strangers», sayfa 2

But talking to the trumpeter wasn’t the only reason they were there at Small’s Paradise. It was safe, safer than anywhere else. Harlem was the right side of Central Park, that’s to say the wrong side; it was nobody’s territory, at least nobody she knew, nobody who mattered.

The black trumpeter was playing now, standing up for a short, final solo as the band came to the end of ‘Caravan’. Cavendish knew it; he’d been at Small’s once before when Duke Ellington was playing. He liked swing; it was the sound he heard everywhere in New York. But the man at the piano, with the immaculately slicked hair and the faintest pencil-line moustache, went further than swing. What he played wasn’t just music, it was the city itself; it was as delicate and ephemeral as it was hard and sharp and solid. The piano was the night air in Central Park one moment and a subway train the next. As the trumpeter sat down to a scattering of applause, the piano and the brushed cymbals took over. Cavendish took an envelope from his pocket and pushed it across the table to Kate. The music was louder again now as the band played the last, almost harmonious chord, and the whole club focused on Ellington and his musicians, clapping and shouting.

‘That’s the passport I promised,’ said Cavendish. ‘Two. If she needs to travel under another name, there’s not much point you travelling under yours. It’s unlikely she’ll want it going into Canada, but with what’s going on at the moment you don’t need a problem.’

Kate picked up her handbag and put the envelope in it.

‘My problem right now is she’s still there, locked up in that place.’

The set had finished now, and the fading applause followed Ellington and his band off the stage. Another musician made his way to the piano and started to play, more quietly. Dancers drifted off the floor; the volume of conversation grew; trays of food and drink were coming at greater speed.

Jimmy Palmer, the trumpeter, pushed his way through the milling customers and waiters and cigarette girls, and sat down at the table with Kate O’Donnell and John Cavendish without saying a word. He lit a cigarette.

‘So where are we, Kate?’ he asked.

‘John’s at the Canadian border. I haven’t got her off Long Island.’

She smiled as she said it, but it wasn’t a joke.

‘You really think he’s going to come after her?’ said Cavendish.

‘We’ve been having this conversation for a month, John.’ Kate was tired repeating herself. ‘You’ve talked about helping us, and then you’ve talked about helping us, then you’ve talked about it a bit more. He won’t let her just go. How many times do I have to say it? She wouldn’t be there in the first place if he was happy to let her go. If you’re not going to do it –’

Jimmy Palmer just drew on his cigarette and watched.

‘I need to be sure how careful we need to be, once we get her out of New York,’ the army officer continued. ‘The answer’s still very. So you get her away from Locust Valley and I’ll make sure you cross into Canada. I’m not trying to find a way out of it.’ He took out a cigarette himself now; he caught the eye of a waiter and gestured for another round of drinks. ‘I’ve said I’ll use my car. There’s not going to be anybody around to make a connection between you and an Irishman taking a little trip upstate –’

‘I can get a car.’ It was Jimmy who spoke now. ‘I can do the trip.’

Kate smiled, reaching out her hand fondly to take his. He spoke with determination. It mattered to him in the same way it mattered to her. It was different for Cavendish; of course it was. He was there for what he could get. But he was the one they needed. He had the false passports.

‘I know, Jimmy. But there’s too many connections already. He knows you too. Anybody he sends after Niamh is going to know you. And people are going to notice a black man driving two white women around upstate.’

‘Poor old Jim Crow, eh?’

He gave a wry smile. It didn’t make the truth any easier. Harlem was his place; he was somebody here. Outside Harlem he wasn’t anybody at all.

‘I guess I know you’re right.’

He shrugged; you couldn’t argue much with how things were.

Kate turned back to Cavendish.

‘I have talked to her. I’ve told her what she has to do. It’s not easy. Once she’s out of there it’ll be different. Once she can breathe. Half the time she’s so doped up she doesn’t know what I’m saying. I don’t know who’s listening either. I am sure she can do it. It’s just getting her to walk out –’

‘That bit’s down to you,’ said the Irishman quietly. ‘When we’re out of New York it should be fine.’ He picked up his drink. ‘But I still need what I need from her. I need her in a state where she can think clearly.’

She nodded. He held her gaze for a moment. Maybe there was a part of him that was doing this because he had started to care now, about Kate and about her sister. But that wasn’t why he was there. And Kate knew it.

‘Niamh does know that. She has got the information.’

There was silence. Kate picked up her drink. She was tense again. Jimmy Palmer looked at them both. Whatever they were talking about didn’t include him.

‘Does know what?’ he said, his eyes on Kate. ‘What’s this about?’

‘It doesn’t matter, Jimmy.’

She was awkward rather than dismissive, but it came across as dismissive anyway. Cavendish wouldn’t want her to talk about any of that.

‘It matters to me. And it sounds like it’s going to matter to Niamh.’

The trumpeter turned to Captain Cavendish again. He didn’t know him. He didn’t know why he was involved, why he was giving out passports and booking liner tickets. He didn’t like the fact that he was taking things over, in ways that weren’t explained, ways that seemed to be about something a lot more than helping Kate O’Donnell and her sister because he was a nice guy. He had only met the captain three times; he didn’t always feel like a nice guy. He watched people too much. ‘So this’ll be some li’l thing the nigger don’t need concern hisself with, that right Massa John?’

‘Come on, Jimmy. It’s nothing of the kind,’ said Cavendish.

‘Maybe this nigger should know about it, Kate,’ snapped Jimmy.

‘He’s not helping us for love,’ said Kate, shaking her head. ‘You must have worked that out. He wants something out of it. You know what Niamh was doing on the boats. You know she wasn’t just any old courier either. Why should the captain do anything for nothing? Why should anybody? He’s a soldier, an Irish soldier. You know what I’m talking about too.’

John Cavendish wasn’t comfortable with what Kate was saying, but he didn’t stop her saying it. He looked across at Jimmy Palmer and nodded.

Jimmy didn’t like it but he could work it out, enough anyway.

‘We can’t do this on our own,’ said Kate. It was all she could offer.

The trumpeter stubbed out his cigarette. The waiter arrived with the fresh drinks and passed them round. Palmer downed his bourbon in one.

‘If there’s a deal, then you do your part, Mr Cavendish. She can’t stay there. And days, not weeks. Kate’s seen her. She can’t take much more.’

‘I’m ready to go.’ John Cavendish looked from Jimmy to Kate.

Jimmy was looking at Kate now too.

She nodded.

Ellington’s band was straggling back on stage.

‘I got the taxi,’ said the horn player, getting up. ‘Just give me the day.’

Kate nodded again. She picked up her drink.

Cavendish raised his and smiled.

Jimmy reached out his hand. John Cavendish shook it.

Kate smiled at them both. It wasn’t much of a smile. She looked tired.

The trumpeter walked back to the stage.

‘Do you want a lift, Kate?’ She shook her head.

‘No, I’ll get a cab.’

‘Sure?’

‘It’s better we’re not seen together outside work.’

She was right.

Suddenly Duke Ellington’s hands hit the piano hard. The drummer crashed the cymbal and top hat. Jimmy Palmer’s horn was loud and liquid.

Outside it was cold. Kate O’Donnell slipped away, with no more than a last smile, a stronger smile now, and hailed a cab. John Cavendish watched her go for a moment, conscious that he had been delaying things. He didn’t know what the consequences would be, that was all. There was no obvious connection to make between a woman escaping from a sanatorium on Long Island, where she was virtually a prisoner, and the IRA’s courier system and its ciphered messages to and from America. But if the IRA was as careful as it ought to be, someone could decide changes were in order anyway, and that might mean his interceptions drying up. He pushed away all that and walked towards 7th Avenue to get his car. It was time to act; a file full of ciphers nobody could read was no use to anybody. He needed Niamh Carroll now.

The night was bright and noisy all around him; car horns, laughter, singing, angry voices, somewhere a saxophone, the rattle of the trains from the el. It was still Ellington’s music, all of it.

At the corner with 7th Avenue there were a few people standing in front of a small black man, not old but with strikingly white hair, who stood on a box speaking. In front of him there was a placard: The Ethiopian Pacific Movement – the Struggle between the New Order and the Old. People drifted by. Some paused, then walked on quickly. The night swept round the white-haired man. John Cavendish did stop, listening to his words. He had seen the man before.

‘You think there’s going to be change while those sonovabitch Jews run things? Even the white man’s starting to listen now. Even the white man’s got someone telling him what’s righteous. You heard of Adolf Hitler? Now, he’s a man got those sonovabitch Jews on the run. When he’s kicked their butts, well, the white man can have Europe, that’s all Hitler wants. He wants us to have our place and whitey to have his. Black place, white place. That’s the world we want. So Herr Hitler is fighting our battle for us. He’s fighting against white democracy, because white democracy is the biggest shit lie the Devil ever put on the earth. And you know what Herr Hitler’s going to do? He’s going to take Africa from the British and give it to the black man. That’s coming brothers, believe me! And we got other friends too, not just Mr Hitler. We got the Japanese now. They want to kick the white man’s ass out of the Pacific, like Hitler will in Africa. They’ll kick it so hard you won’t see a white man or a fucking sonovabitch Jew for dust!’

The words puzzled Cavendish now as they had puzzled him before, but the light of truth shone in the black man’s eyes. He was looking at Cavendish, with a slight smile, only now registering his only listener. The captain smiled back amiably, pulled his hat on tighter, and walked off.

*

When Donal Redmond left John Cavendish’s car in Queens he had walked two blocks to Lennon’s Bar, the call house where the messages he brought from Ireland were dropped. He walked in through the bar, nodding to the barman and the two or three customers who were there, and headed straight for the back room. He knew the place; he knew the routine. And there’d be a couple of drinks afterwards. He opened the door into Paddy Lennon’s office.

The old man was sitting at his desk, a green shade over his eyes, totting up figures. The room was tiny, lined with ledgers and files, the desk piled with skewered bills and receipts. Paddy raised his eyes and pushed up the shade.

‘You’re late.’

‘Why the fuck’s everyone always telling me I’m late?’

‘Maybe it’s got something to do with the time.’

‘Is there a clock on this?’

Paddy Lennon simply smiled, but it was an odd sort of smile.

The steward put down his duffel bag and got out the Jacob’s tin.

The bar owner took it and put it in a drawer in the desk.

‘You should stay off the booze till a job’s done, Donal.’

‘I don’t take orders from you. I deliver and you collect. That’s it. I get my orders in Dublin. The job is done and that’s that. The way it always is.’

‘The way it always is,’ said Paddy, pulling down his eye shade.

As Donal Redmond walked back to the bar there were two men standing in his way. One of them was a uniformed NYPD officer. The other man wore a grey raincoat and still had his hat on. He was a policeman too, a detective. He didn’t need a uniform for the ship’s steward to know it.

‘Mr Redmond?’ It was the detective who spoke.

‘That’s right.’

‘I’d like a look at your passport and your papers.’

‘What for?’

‘Some sort of mix up, that’s all.’

‘What sort of mix up? I’m straight off my ship.’

The detective ought to have sounded apologetic; he didn’t.

‘We can give you a lift down to the precinct house. The sergeant just wants to look over the details. You can be on your way then. Will we go?’

There was something odd about the way they were looking at him. It wasn’t unpleasant. It wasn’t anything. But it was the same way Paddy Lennon had been looking at him in the back room. Donal Redmond knew he didn’t want to go with them. The detective opened his coat to pull out a packet of cigarettes. As he did Redmond saw the shoulder holster and the gun that sat in it. The detective didn’t take a cigarette from the packet. He was making a point. And the point was made.

As the three men left the bar, conversation among the customers resumed, as if they had never been there.

*

It was two days later that John Cavendish, sitting in the coffee bar across from the Irish Pavilion at the World’s Fair, reading The New York Times, saw an item at the bottom of page seven. A man’s body had been pulled out of the Hudson River. He had been identified from papers in his pocket as Donal Redmond, an Irishman who had only just arrived in New York; he had worked on the French Line boat, the Normandie, as a steward. It was believed that he had fallen into the Hudson from the ship, docked at Pier 17, when drunk.

It seemed that the captain’s source had dried up now anyway. There would be no more IRA ciphers. He had to hope that they had enough to find out what was going on, and he had to hope that Kate O’Donnell’s sister Niamh could give him what he needed most of all, the key to break the code, because no one was getting anywhere with deciphering the stuff in Dublin. He had hoped to get a bit more out of Donal Redmond though. He was disappointed; but probably not as disappointed as Donal had been himself.

3. Kilranelagh

West Wicklow

Garda Sergeant Stefan Gillespie was walking slowly down the stairs in the stone farmhouse below Kilranelagh. He was tired. The first ewes were lambing; he had been out in the haggard field behind the hay barn with his father till five in the morning, and now it was only eight. The smell of new life and morning frost was still in his nostrils; the clothes he’d lain down in were spattered with blood and urine, stiff with the grease from the ewes’ fleeces. Four twins, two singles, and only one born dead, strangled by its umbilical cord before he could get his hand in to turn it. There was a frail, dark triplet the ewe would have no milk for, to be reared for a time by the kitchen stove.

He had only been half asleep as the telephone started to ring. If his father was in bed and his mother was in the kitchen, it might ring till he answered it. It sat on a shelf by the front door, still looking very new, its black Bakelite shining; it had been there for almost a year now and it was polished more than it was used. It rang rarely enough that when it did Helena Gillespie would emerge from the kitchen and look at it for a few seconds, with an air of mild trepidation that she had not yet quite shaken off, before picking it up and speaking into it, slowly, carefully and loudly. She was coming out of the kitchen now, drying her hands on a tea towel. She smiled as Stefan arrived at the phone at the same time she did, and turned to go back to the breakfast she was cooking.

Tom Gillespie, Stefan’s nine-year-old son had got up from the breakfast table and was peering out. ‘Who is it, Oma?’ His grandmother shrugged. ‘It’ll be for your father. It always is.’ And it was. Superintendent Riordan was calling from the Garda barracks in Baltinglass.

‘You’re to go up to Dublin, Sergeant. They want you at headquarters as soon as you can get there. There’s no point coming in here. You’ll need to shift if you’re going to catch the train.’ Riordan was oddly formal. He would normally have called his station sergeant by his name, but since the message he had just received came from the Commissioner, this was a standing-up sort of phone call. There was also a hint of irritation in his voice; he didn’t like passing on a message from the Garda Commissioner to one of his officers when no one had had the courtesy to explain anything at all to him.

‘What’s all this about?’ asked Stefan.

‘If you don’t know, I’m sure I don’t.’

‘Well, I haven’t got the faintest idea, sir.’ Stefan smiled; he heard the irritation now; the ‘sir’ might help. He looked down at the clothes he was in. No one expected him in at the station today. ‘I’d better put a clean shirt on.’

‘The Commissioner wants you at eleven, so don’t piss about.’

The phone went down at the other end before Sergeant Gillespie could ask any more questions. Stefan walked into the kitchen, puzzled. Tom was eating his bacon and egg slowly, peering across the plate at the book he was reading, The Adventures of Tom Sawyer. Once he had grasped that the call was what most calls were at Kilranelagh, for his father, just another message, summons, query, instruction from the Garda station, he had lost interest. Helena was about to put another plate of bacon and egg on the table. Stefan reached out and picked up some bacon with his fingers and popped it in his mouth. That would have to do for breakfast.

Her lips tightened as she looked at his clothes.

‘Jesus, could you not have taken those off when you came in?’

He winked at Tom; Tom laughed.

‘Do you like making work for me, Stefan?’

‘You know I do, Ma!’

She turned back to the stove with a puff of irritation and a smile.

He leant across her and took another piece of bacon.

‘Have we got no plates now?’

‘Sorry, I haven’t got time.’

‘Why not?’

‘I’ve to be in Dublin. I’ll only just get the train.’

‘Why?’

‘I don’t know. They want to see me at Garda HQ. They didn’t tell Gerry Riordan what it was about. I could see the expression on his face coming down the phone line at me!’ He laughed again, grabbing an apple from the bowl on the sideboard. He looked down at the lamb, sleeping in a cardboard box by the stove. ‘And don’t forget her, will you Tom?’

‘I won’t,’ his son nodded, still reading, not looking up.

He ran upstairs a lot faster than he’d come down. He wasn’t tired now. In a place where not much happened, anything happening was an event.

In the farmyard David Gillespie was driving a cow and a calf into the loose box next to the barn. Stefan took the bicycle that was leaning against the wall by the front door and cycled out round his father and the cow and calf; the cow stopped, bellowing darkly, and nudging her wobbling calf away.

‘I don’t know what time I’ll be back, Pa. I’ve to go to Dublin.’

His father nodded and tapped the cow’s backside.

‘Your Ma said.’

‘Ned Broy wants to see me. And pronto, apparently!’

‘What have you done?’ said David with a wry smile.

‘He’ll be worried about the sheep stealing again, I’d say, Pa.’ He rode out of the farmyard, down to the road.

His father watched him for a while, remembering the years that had passed since his son was last called to Garda Headquarters. At the end of all that Stefan had left his job as a detective in Dublin, and had come back to Baltinglass to work as a uniformed sergeant in the small West Wicklow town. It had been his own choice, driven as much as anything else by the responsibility he felt to his own son. Tom was only five then, living with his grandparents on the farm, seeing his father once a week, sometimes less. The four years that had passed since then had been happy ones for the most part, but in a family where emotions were sometimes as deeply hidden as they were deeply felt, David Gillespie knew that what his son gave to that happiness came at a price.

It wasn’t a price Stefan begrudged, but it was still a price. His life had been on hold. There were things that weren’t easy; there were corners where the comfortable contentment the Garda sergeant showed his Wicklow neighbours was less than comfortable. He lived in a place he loved, with the people he loved. It was what he had felt he had to do; it was not all he was.

For Stefan’s mother it was simple enough; all that was missing was a woman, not to take the place of her son’s now six-years-dead wife, Maeve, but to fill the empty places.

David Gillespie knew it went further than that. A long time ago he had put his own life on hold, for very different reasons, and he had come back to the farm above Baltinglass to give himself the space to breathe. He had breathed the air that came down from the mountains very deeply, and like his son he loved it, but it was a narrower life than he had wanted, with all its gifts. David had found a way to calm what was restless and dissatisfied in himself; perhaps he had nowhere else to go. But he recognised the same restlessness in his son; he recognised that it went deeper too.

He looked round the farmyard for a moment, then up at the hills that surrounded it, Keadeen, Kilranelagh, Baltinglass Hill. It was a great deal, but it would not be enough, not the way it had been for him, even if Stefan had persuaded himself it could be. David Gillespie shrugged, and turned back to the suspicious cow and her calf, driving them into the loose box.

Inevitably some of the same thoughts came into Stefan’s head as he cycled through Baltinglass’s Main Street and along Mill Street to the station, but it was easier to think about the present than the past. As he sat on the train following the River Slaney north towards Naas and Dublin, he looked out of the window and thought how little what he’d been doing in recent weeks could interest the brass in the Phoenix Park. He smiled. Sheep stealing really was about as serious as it got.

There was the new Dance Hall Act, of course, which required all dances to be licensed in light of the moral dangers the Church felt were inherent in dancing. A spate of unpopular raids was taking Stefan into the courthouse in Baltinglass on a weekly basis now. Yesterday he’d been giving evidence against the Secretary of the Dunlavin Bicycling Association and the Rathvilly Association Football Club. Admittedly the Dance Hall Act was causing considerable anger among the unmarried guards in Baltinglass who, when they weren’t raiding the dances, were dancing at them.

Then there was the pen of in-lamb ewes he was pursuing, that had disappeared from Paddy Kelly’s farm on Spynans Hill in February. Christy Hannity had bought them from Paddy at a farm sale and swore blind the old man had put them back on to the mountain while he was in the pub. It wasn’t the first time Paddy Kelly had played this trick and got away with it. All he had to say now was that mountain sheep had their own ways and Christy was too drunk to remember what he’d done with them.

And there were two days wasted on James MacDonald who had assaulted the Water Bailiff, Cathal Patterson, after refusing to give up a salmon found in his possession by the Slaney. He claimed the salmon was a trout, which he had since eaten. As for the Water Bailiff’s nose, didn’t he break it himself, tripping over a dead cat as he was walking out of Sheridan’s Bar?

It was hard to push the past out of the way altogether as Stefan walked from Kingsbridge Station through the Phoenix Park to the long, low stone building that was part eighteenth-century army barracks and part Irish country house. Nothing very much had happened in the last four years; most of what had, had happened to his son. He had no problem with that; it was why he had left CID, why he had left Dublin, why he went home. But the thought of how easily and how completely he had left behind the job he had always wanted, since the day he joined the Gardaí, had never struck him as starkly before as it did in the few moments he spent waiting outside Ned Broy’s office.

It hadn’t only been about Tom of course. He had also left because it suited everybody, the Garda Commissioner included. He had been involved in investigating two murders that in the end nobody wanted investigated too publicly. There had been justice of a kind, finally, but it had been a rough justice that the Irish state didn’t want to know about.

For a time it had been easiest for Detective Sergeant Gillespie to become plain Sergeant Gillespie in a country police station. No one had really meant him to stay there so long. He hadn’t intended that himself. It just happened, because that was what was best for Tom. Now, as Stefan sat in Ned Broy’s office again, he could feel an awkwardness in the Garda Commissioner. Sergeant Gillespie’s submerging in a backwater had not been what he had intended either.

Whatever was urgent, the Commissioner’s opening words weren’t.

‘So, how’s West Wicklow?’

‘Quiet enough, sir.’

‘You’re keeping Gerry Riordan in check, I hope.’

‘Well, mostly he does what he’s told.’

The Commissioner smiled. There was a moment’s silence.

‘You’ve been there a long time.’

‘Four years doesn’t seem so long. Time goes fast enough.’

‘Bollocks, you’re not old enough to say that yet.’

Stefan laughed. They were only words, but the Commissioner was looking at him quizzically now, remembering what had happened before.

‘Your father’s well? And your lad?’

The Commissioner had a good memory at least.

‘We’re all grand.’

‘And you’re happy down the country?’

‘Happy enough, sir.’ Stefan was aware that the polite remarks, whatever was about to follow, meant nothing to Broy, but it was the first time anyone had asked him such a direct question about his job, and by extension his life. The answer he gave was the answer any Irishman would give to such a question; an answer that could mean anything from despair to exultation, and everything in between. He was aware that he was avoiding a direct answer, not for the Garda Commissioner’s sake, but for his own.

‘A woman is missing.’

Broy suddenly stood up and moved slowly towards the window that looked out on to the Phoenix Park. The trees were still bare. Spring wasn’t far away now, but it still felt like winter.

‘There is every reason to believe she’s dead, and that she was killed.’ He turned back from the window. ‘The fact that she’s missing is the only thing that’s been in the newspapers so far. We can keep it like that for a little longer. And it’s helpful that we do, for various reasons. She is a Mrs Leticia Harris, with a house in Herbert Place.’

‘I think I did read something about it, sir.’

‘The evidence from the house, along with Mrs Harris’s car,’ continued the Commissioner, ‘indicates that she was the object of a very brutal attack in her home. Her car, however, was found in the grounds of a house close to Shankill, by the sea in Corbawn Lane. It’s clear she had been in the car, or her body had. At the moment we believe she was killed at the house in Herbert Place, or at least that she was dead by the time she reached Corbawn Lane, where the body was probably taken from the car and thrown into the sea. What the tides have done with her is anybody’s guess at this point.’

It was odd, but Stefan could feel his heart racing slightly. It was an unfamiliar feeling. It was excitement. It was four years since he had worked as a detective, but the instincts that had made him good at his job were still there. He felt as if a light had just been switched on inside his head.

‘Mrs Harris has a son. Owen. He’s twenty-one years old. I don’t think we know enough about him to understand what kind of man he is, but we know his relationship with his mother was very difficult, in all sorts of ways. Some of those ways had to do with money. Mrs Harris has lived apart from her husband for a considerable time, over ten years in fact. He’s a doctor, of some note, with a practice in Pembroke Road. From what Doctor Harris has told detectives, I think you’d describe the relationship between mother and son as highly strung, which is a polite way of saying they were a bloody peculiar pair. Superintendent Gregory at Dublin Castle is in charge, but it’s a big operation, involving detectives from several stations, as well as Special Branch. The short version is that we believe Owen Harris murdered his mother and dumped her in the sea.’

‘And where is he now?’ asked Stefan. The Commissioner’s tone of voice told him that wherever he was he certainly wasn’t in Garda custody.

‘New York.’

‘That was quick work.’

‘He left from Cobh two days after his mother disappeared.’

‘So is he in custody? In New York?’

‘No, but we know where he is.’

The Commissioner sat back down again, his lips pursed. It was more to do with irritation than anything else. Stefan could already sense this case was about more than a suspected murderer. Broy opened a file on his desk.

‘Mr Harris is at the Markwell Hotel, which is somewhere near Times Square – 220 West 49th Street to be exact. It’s felt there’s no need for his arrest or extradition.’

Stefan was aware this was a slightly odd way of putting it, as if it wasn’t entirely the Commissioner’s decision.

‘He’s agreed to come back to Ireland voluntarily to be interviewed, as soon as possible, as soon as practical. That’s why you’re here, Sergeant.’

This may have been the most interesting conversation Stefan Gillespie had had in a police station since he went to Baltinglass as station sergeant, but so far its purpose was as clear as mud. He looked at Broy blankly.

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.