Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

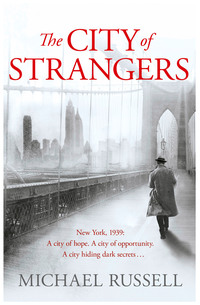

Kitabı oku: «The City of Strangers», sayfa 6

Terry Gregory drained the whiskey in his glass and stood up.

‘It’s an ill wind, eh Sergeant?’

He walked out to the lobby and into the street.

In the room Valerie was sitting up, reading. She laughed as Stefan came in.

‘What was all that about?’

‘The man I’ve got to bring back from New York has disappeared.’

‘So aren’t you going?’

‘They’ll find him. Well, that’s what the superintendent said.’

He shrugged. She said no more. As he sat down on the bed she stretched out her hand to touch his back. He sat there for a moment, not moving, feeling her fingers. He was aware how much he liked her. That was the thought in his head that made him smile. It wasn’t love between them, it never had been, but it wasn’t nothing, for either of them. He turned round and reached across the bed, stroking her hair. As he kissed her she pulled him slowly down on to her. Neither of them needed to speak now to know that this would be the last time they would make love.

6. West Thirty-Sixth Street

New York

Longie Zwillman stood at the counter in the window of Lindy’s diner on Broadway, between 49th and 50th. He kept his hat on and his overcoat done up, though it was warm enough in Lindy’s. He was thirty-five; he didn’t look older but somehow people felt he was older. There was age behind his eyes, and behind the half smile that was almost always on his lips there was nothing that suggested he found very much to laugh at. He was drinking the cup of coffee and eating the cheesecake Clara Lindermann had brought him personally.

It was busy in Lindy’s, but there was space at the window where Zwillman stood looking out, seemingly at nothing in particular. The two big men in homburgs who stood behind him would have made sure there was space, because Longie didn’t like people too close to him; even in a New York diner he expected the courtesy of space. But they didn’t have to make room for him. There was something about the way Longie held himself, and the way he looked at people when they came near him, that ensured he rarely had to ask for anything. He was a courteous man though; he seemed to inspire courtesy in others. Broadway wasn’t his territory; neither was Manhattan. He had come over from New Jersey. But he was respected here as he was respected everywhere. The work he had today crossed no lines. It wasn’t business. It was pest control, and he had an interest in that.

Outside the window, across the sidewalk, a truck stopped. It was a fish truck, one of the hundreds that pulled in and out of Fulton Market every night. The driver looked through the window at the man in the overcoat, eating the last forkful of Lindy’s cheesecake. Zwillman nodded. The truck drove on.

Longie finished his coffee and walked out on to Broadway, followed by the two big men. He sauntered down towards Times Square. He went almost unnoticed in the afternoon crowds bustling up and down around him, but not entirely. Several people recognised him and nodded respectfully. He nodded in return. Several times men walked up to him and spoke, in low tones of respect, asking after his health and the health of his family. They waited for him to stretch out his hand before they attempted to shake his. Two NYPD officers were among those who stopped and received an invitation to shake that hand.

In all the unseeing and indifferent noise of Broadway, Longie Zwillman walked like a secret island of calm and courtesy, or so it seemed. He knew who every one of the people who greeted him was, even out of his own fiefdom; and they were grateful for it. To know him and to be known by him was something. To lose those small favours was something else; after all respect and fear weren’t very different.

There was the beginning of darkness in the grey March sky over Times Square, and the lights all along Broadway were beginning to push the trash and the seedy corners out of sight. Crowds jammed around the 42nd Street subway as the people heading home from work met the people coming out to the theatres and movies, restaurants and clubs, or to do what most people did on Broadway, to be there and to walk about.

Pushing up from the subway, through the hundreds of New Yorkers streaming down, was a group of men, a dozen or so, all beered up for the evening in advance. They were rowdy already, laughing loudly and looking around with a kind of purpose and anticipation they seemed to find funny and exciting all at the same time; they were their own entertainment. But there was an aggression in their laughter that was more than just a bunch of guys with too much beer inside them. Several of them carried bundles of newspapers; one carried a furled flag; another carried billboards. Two of the men wore distinctive silver-grey shirts with a large L on the left side, in scarlet, close to the heart; the uniform of the Silver Legion of America. When they stopped on the corner of Broadway and 43rd they were quieter, gathering around the flags.

The newspapers were handed out, the billboards propped against a store front, the flags unfurled. The flag was the red L on silver; L for the Legion, L for Loyalty, L for Liberation. The placards bore scrawled headlines from the newspapers the men were selling: Social Justice, Liberation, National American. ‘Buy Christian Say No to Jew York!’ ‘Keep Us out of England’s War!’ ‘The Protocols of Zion and the End of America!’ ‘Roosevelt Public Enemy Number One!’ They moved along Broadway in twos and threes, hawking their papers, and shouting the headlines.

They were all New Yorkers, with names like other New Yorkers; mostly they were German and Irish names. But they weren’t only there to sell; they were looking for the enemies of America in the streets of their city; anyone they thought might be a Jew.

Dan Walker was already bored calling the headlines of the papers he never read anyway. He wanted another beer. Van Nosdall was a lot keener, thrusting out blue mimeographed slips as he moved through the crowds. ‘There’s only room for one “ism” in America, Americanism!’ ‘Democracy, Jewocracy!’ ‘Hey, Yid, no one wants you here! We’re coming for you!’ As he screamed ‘Coming for you!’ at an elderly couple, heading to the theatre, he formed his fingers into a pistol and laughed. ‘Pow!’ Dan Walker yawned.

‘Let’s get a beer for Christ’s sake!’

Then he stopped and smiled.

‘See the piece of shit there –’

He was looking at a boy of sixteen or seventeen, with a thin face and large, dark eyes. Anyone would have said he was Jewish. You could always tell a Jew of course, but this one was Jewish Jewish. He was staring at the two men with real anger in his face, and he wasn’t moving; he wasn’t trying to run the way he was supposed to. Dan Walker walked forward, with new enthusiasm for the slogans he had been leaving to Van Nosdall till now. He walked up to the youth, who was standing his ground, quietly unyielding.

‘Read Social Justice and learn how to solve the Jewish question.’

The Jewish youth nodded, unexpectedly.

‘OK, I’ll take one.’

It was an odd response; he should have already been running.

Dan Walker looked round at Van Nosdall.

Nosdall shrugged. He handed over a copy of Social Justice, and the youth handed him some change. As he opened the paper the youth glanced at the contents, with a look of deep seriousness. He turned a page.

‘I’ve been reading Father Coughlin’s articles about the Protocols of the Elders of Zion. It’s certainly some piece of work, some piece of work.’

He folded the newspaper up and put it in his pocket.

‘I’ve never seen shit like it. So this is what I’m going to do – I’m going to take it home and wipe my arse with every last, lying, fucking page.’

With that he ran, out into Broadway, through the traffic.

Dan Walker and Van Nosdall were already running after him. The bundle of papers was dropped. Dan put his fingers in his mouth and whistled shrilly. This was what they were all waiting for, this was real politics. And while a couple of men remained behind to pick up the newspapers the whole gang that had emerged from the subway only ten minutes earlier was racing through the blasting horns in pursuit of the young Jew. They had one now. And as long as they kept him in sight, they would run till they caught him.

He was in west 44th Street now, heading towards the Shubert Theatre. The street was quiet after Broadway and 7th Avenue; the theatres weren’t open yet. He looked round. They weren’t far behind. The other men had almost caught up with the two he had spoken to already. There were at least a dozen of them. He turned right abruptly, into the alley that ran between the Shubert Theatre and the Broadhurst. The gates were open. He stopped for a moment, catching his breath, and walked between the two theatres for a moment.

It was dark here now, and it was a dead end. At the top of the alleyway Dan Walker and Van Nosdall were standing, watching him. The youth turned round, and stood looking up at them. The other men were there now. They grouped together, extracting a variety of batons and coshes and knuckle dusters from their coats, grinning and joshing one another. They produced a wailing wolf-like howl, all together, and started to walk down the alley towards the Jew.

He seemed remarkably, unaccountably unafraid.

Quite suddenly a door out from the back of the Broadhurst Theatre opened. The youth gave a wave to the advancing party and walked into the theatre. The door closed. The men ran forward. It was a fire exit; it was heavy, blank; it had no lock or handle on the outside. Two of the newspaper sellers hammered on the door.

At first only one man turned round and looked back up the alley. A truck had just stopped there and in the light from 44th Street he could see a gang of men getting out of the back. Some of the others were looking round now; then they all were.

The whole street end of the alleyway was blocked by a small crowd; there were a lot of men there, twenty-five, thirty. They carried baseball bats and pickaxe handles. There was complete silence for some seconds. No one was hammering on the Broadhurst fire door now; no one was laughing. The men from the fish truck filled the alleyway. They moved in a line towards the men from the Silver Legion and the Christian Front, looking for healthy political debate.

On West 44th Street Longie Zwillman’s Pontiac passed the fish truck. The driver, closing the back doors, touched his cap as the car approached.

The Pontiac carried on into Broadway.

*

There wasn’t much that was old in New York. Keens Chophouse on West 36th Street was as old as most places that were still standing. It had been there long enough that clay pipes still hung from the ceiling where long-dead customers had kept them. It smelled of old wood in a city where that smell was barely known. John Cavendish sat upstairs on the raised platform in front of the small-paned windows that gave on to 36th Street.

It was still early and there were few customers, but those there were, were kept well away from the table the Irish army officer was sitting at. It was Longie Zwillman’s table. Cavendish waited. He had been there for half an hour. It wasn’t a problem. Half an hour to sit and do nothing was welcome; half an hour to sit and think of something other than what he was doing. He thought of his wife and his children in Rathmines. It would be another two months before he went home. It was hard. He didn’t often let himself think about how hard it was. Whatever New York was, there were moments when it really wasn’t much at all, if you only stopped long enough to take a breath.

They talked for half an hour about nothing in particular: how old their children were; what was the most impressive thing at the World’s Fair; the news from Europe. They were almost strangers but for reasons neither of them was entirely sure about they trusted one another. Each had information the other wanted, or at least had some chance of getting it. As the main course arrived Longie Zwillman took out an envelope. Inside were several small photographs. He fanned them out on the table like playing cards. There was a brownstone building, cars, half a dozen men going into the building or coming out. Some faces were very clear, some indistinct.

‘This is the German bookstore on 116th Street. There’s a lot of stuff distributed there, not just American Nazi Party pamphlets and Bund papers, but pretty much any pro-German, Roosevelt’s-a-commie, anti-Semitic, democracy-will-eat-your-kids crap you can think of. Silver Legion, Christian Front, Social Justice, National American. You’ve seen all that already.’

‘Some of it.’

‘You’ve seen some, you’ve seen the lot. They got a meeting hall upstairs. Same people, same crap. Some of my boys keep an eye on it, to see who’s making all the noise. I got some friends who like me to do that. So it’s a favour. Also it’s where they get together to maybe go out and beat some Jews up, or just some people they don’t like, who mainly happen to be Jews. But that’s not compulsory, Jewish I mean. There’s a lot of people they don’t like. As an American I don’t regard that as entirely reasonable behaviour.’

Longie Zwillman shrugged. Captain Cavendish looked at the photos.

‘Anyone you know?’

The intelligence officer picked up four of the photographs.

‘James Stewart,’ he said, laying one of them down again. ‘I know him. He’s a Clan na Gael man in the Bronx. I wouldn’t have said he was that important, but he is close to Dominic Carroll. He raises a lot of money that goes to the IRA. He has a cousin who’s an anti-Roosevelt congressman –’

‘He’s a Christian Front man now as well,’ said Zwillman. ‘He’s not out in the street, but he’s been at some meetings where they put together a bunch of street fighters, mostly German and Irish. He says a lot of them are ex-IRA.’

‘I wouldn’t take too much notice of that. Give me a dollar for every Irishman in New York who was in the IRA and I could buy up Manhattan.’

John Cavendish put down another card.

‘Joseph McWilliams. I’ve seen him at a few Irish-American bashes. He’s big on anti-British campaigns of one sort or another, that’s all I know. But I wouldn’t have said he’s anybody big in Irish-American politics now.’

‘He’s big on the German side.’ Zwillman spoke again. ‘He speaks at a lot of Bund meetings, about Germany and Ireland – together against the British and the Jews. I guess you know how that goes. Maybe he’s a useful go-between. He speaks good German too. This meeting was no rally for the masses, though. This was small; a dozen people, Irish and German. He’s a somebody somewhere.’

Cavendish nodded; it was good information. He put down the next photo.

‘This one’s a man called Aaron Phelan. Clan na Gael organiser from Queens, and an NYPD captain. He’s also as pally as you can get with Dominic Carroll. And you know who he is now – Clan na Gael president.’

‘And the IRA’s man in New York.’

‘That’s him. If Phelan’s there, Carroll is involved in it too.’

‘So who’s left?’

The G2 man put down the last of the four photographs.

‘An old friend,’ he smiled. ‘I knew he was in New York. It’s interesting to see he’s not just giving speeches at Hibernian Club dinners.’

‘Who is he?’

‘He’s the IRA chief of staff, Seán Russell.’

‘So what are they all talking about, the German Bund and the IRA?’

John Cavendish shook his head.

Zwillman picked up the photographs.

‘I’ve got some friends who’ll want a look at these too.’

Cavendish knew enough not to ask who Zwillman’s friends were.

‘What about these women?’ said the American.

It sounded like a change of subject, but it wasn’t.

‘It’s going ahead. It’ll be the night after Patrick’s Day.’

‘And will you get the information?’

‘She says the sister’s got it. She knows the key to the ciphers. She knows how they work. If I can get both of them across to Canada –’

‘So when does she deliver?’

‘When they’re on their way.’

‘I want to know what this is about,’ said Longie Zwillman. ‘So do you. I got someone inside the Bund. A good man. They trust him. But he doesn’t know nothing about this meeting with the IRA. Nobody does. That’s not how it is. They’re smart as hell when it comes to dressing up in brown shirts and Sieg-Heiling it all over New York, but their organisation stinks. It’s like a sieve. And you don’t seem to think the IRA’s far behind them –’

‘Some of the time,’ replied Captain Cavendish. ‘It depends –’

‘This has got a smell. That’s where it started. You smelt it and I smelt it. But that’s all we have, a shitty smell. They got it well hid. That means it’s got to be worth hiding. You need to open up those ciphers, Captain. This woman has to deliver the goods. If you can’t get it out of her somebody else is going to have to. No maybe. So how about you keep me posted, John?’

The half smile that was always on Zwillman’s lips was still there. His expression hadn’t changed at all. But John Cavendish was conscious that he was dealing with a man who was used to getting what he wanted and didn’t care what happened along the way. The American wasn’t a man to play games with. He had made a mistake telling him about Kate and Niamh at all. It had been necessary to give information to get information back.

It had never crossed his mind that he risked losing control. But the waters were getting deeper. Now he heard the quiet threat in Longie Zwillman’s voice.

7. The Yankee Clipper

Foynes, Co Limerick

It’s the sheer size of it I couldn’t believe. It’s higher than a house. It’s like a liner, sitting in the water, but it’s the wings and the engines that are so big when you climb up under them to get in. One minute you’re on the water, bumping a bit – bumping quite a lot in fact, and then you’re in the air. We were only over Ireland a few minutes, hardly at all, and then we were over the Atlantic. You look down and the sea just goes on and on forever.

The postcard Stefan Gillespie was writing to Tom was growing in length, and his writing was getting smaller and smaller to fit. He had bought the picture of the Boeing 314 Yankee Clipper at the terminal, but Tom wanted it to be written on the plane and sent from America with an American stamp. The card wouldn’t reach Baltinglass till he was back there himself, but it was crucial that it came in the post as far as his son was concerned; that had an authenticity that the picture alone couldn’t have.

Finishing the card Stefan gazed down at the Atlantic again, as he had been gazing on and off for an hour. At 20,000 feet the sky was clear; there was nothing below except the sea, grey and choppy and unchanging, mile after mile after mile, and the long journey was only beginning. But as Stefan gazed down, that unchanging swell had its own fascination. The flying boat felt smaller now, far smaller than it had tied up beside the pontoon on the Shannon.

The cabin of the Yankee Clipper was divided up into small seating areas, with bulkheads closing them off from one another. The seats were leather, still with the smell of newness about them. The floors were thickly carpeted. Halfway along the length of the main cabin there was a small dining room; two stewards, naval-officer navy now exchanged for gleaming white jackets, were setting the tables for the first sitting of dinner, with crisp linen and silverware. Another steward, passing Stefan’s seat with a bottle of champagne, stopped and topped up the glass at his elbow.

The journey that was all about bringing a man home to hang perhaps had become no less strange in all the self-conscious elegance of the Yankee Clipper. But it was still hard not to smile grimly at the prospect of the return, a pair of handcuffs linking him and his prisoner across the plush leather, and both of them with a glass of champagne in each free hand. Whatever crap Superintendent Gregory had given him the night before at the Four Courts Hotel, he had taken one piece of advice; on the way to Kingsbridge Station he had walked round to the Bridewell Garda station, behind the Four Courts, to get a pair of handcuffs.

The flying boat was by no means full. Most of the passengers were already on the plane when it touched down from Southampton, English and American; only three others had got on with him at Foynes. The service had been in operation for barely a month and many of the passengers were wealthy people flying for the experience rather than because they needed to get to America fast.

The smell of money filled the cabin of the flying boat as distinctively as the smell of new leather and the steaks sizzling in the galley at the back of the fuselage. Several passengers had eyed him curiously as they smiled and said hello, not because they knew who he was, but because they didn’t. There was an atmosphere on board the plane, amidst all the tasteful elegance; if you were on the flight you ought to be important enough to be recognisable; you did have some obligation to be somebody.

Across the aisle from Stefan, in the compartment just in front of the galley, a man in his late fifties or early sixties had been immersed in a pile of newspapers, English and Irish, between scribbling notes in a notebook. He had said hello to Stefan, and remarked on the weather, which was pretty good for the crossing to Newfoundland it seemed, and then he’d got on with what he was doing.

He was a thin man, with a thick sweep of grey, almost silver hair; he had the kind of intense, thoughtful face that always has a frown between the eyebrows, even when it’s smiling. From time to time he whistled tunelessly to himself, not loudly, but loudly enough for it to slightly grate on Stefan. The Yankee Clipper was surprisingly quiet, despite the insistent buzz of the four great engines hanging from the wings above them, endlessly turning the propellers. Then all of a sudden the man folded his pile of newspapers together and reached over to put them on the empty seat opposite him. He closed his notebook, put away his pen, and picked up his champagne. He turned towards Stefan Gillespie with a smile.

‘Sláinte!’

‘Sláinte mhaith,’ replied Stefan.

‘First time?’ asked the man.

‘The very first.’

‘Quite something,’ the man continued, glancing out at the sky.

Stefan nodded.

The man got up and walked across the aisle, stretching out his hand.

‘Dominic Carroll.’

They shook hands.

‘Stefan Gillespie.’

The stranger sat down in the seat opposite him. There was nothing particularly unusual about the way he delivered his name, but Stefan got the impression that he expected it to mean something. As he continued to smile at Stefan it was as if he was waiting for recognition of some kind to dawn. It didn’t, and Dominic Carroll’s smile became a grin for a moment, as if he was aware of his own ego, and could find the room to laugh at it sometimes.

‘Where are you from, Mr Gillespie?’

‘West Wicklow, Baltinglass.’

‘I don’t know it. I could place it probably. I’m just about from County Tyrone, Carrickfergus. We emigrated when I was four, so you see it is just about. I’m a New Yorker, heading home. And where you headed yourself?’

‘New York too.’

‘Business?’

‘Of a sort.’

‘And what sort of business are you in?’

Stefan hesitated. He had had no instructions to keep what he was doing a secret, at least as far as it simply concerned who he was. The details were a different matter. But the fact that he was a policeman didn’t tell anybody anything significant; in fact it provided good reasons, without his appearing rude, for him to keep his business to himself.

‘I’m a guard, a policeman.’

The effect of this on Dominic Carroll was unexpected. He looked puzzled, and if not quite angry, irritated. He didn’t like it at all. Then his expression changed and he smiled, pushing away whatever had been there.

‘I know what a guard is, Mr Gillespie. I’m not a stranger to Ireland.’

He spoke easily, wiping out any traces of the feelings that he hadn’t been able to hide seconds earlier. But he was no longer as relaxed as he had been, and as the conversation continued Stefan couldn’t help feeling he was being watched and weighed up. It was hard to work out what was going on. It wasn’t much now, and if he hadn’t registered those first, unfathomable reactions from the American, he probably wouldn’t have noticed at all. Carroll was suspicious; for some reason he was uneasy that Stefan was a guard.

However, time passed and bit by bit the suspicion seemed to fade. Dominic Carroll was a good talker, and like a lot of good talkers he was used to being listened to. Once it was clear that Stefan Gillespie had nothing to say about his business, other than he was doing a job for the Gardaí and would be meeting some NYPD officers, he left the subject alone, except to announce that he knew almost every senior police officer in New York. As Stefan hadn’t got the faintest idea who he’d be talking to, or what would be happening once he arrived in Manhattan, the string of names, all of them Irish, had little effect. The NYPD was soon forgotten but New York was not.

The man who had been born in Carrickfergus was proud of the city he now lived in. He had no doubt whatsoever that it was the greatest city on the face of the earth and that if there was anywhere that represented the future, the future of everything, it was New York, his city. It was no accident that the greatest World’s Fair the world had ever seen had just opened its gates in New York’s Flushing Meadows. Dominic Carroll had played some part in putting that together. The World’s Fair was the world of tomorrow in a box, tied up with red-white-and-blue, star-spangled ribbon and more magical than the stars in the heavens at night.

‘When you fly west, Mr Gillespie, you’re flying into the future. But it’s not just America’s future. One day we’ll bring that future back to Ireland!’

It was hard not to share his enthusiasm. He seemed to have a lot of business interests, so many that it was a struggle to follow them as he fired out details of his early career, his failures and successes, his various bankruptcies and disasters, in building and finance and property speculation. At one point it seemed he had been responsible for building most of the skyscrapers of New York over the past thirty years personally. He caught the amusement in Stefan Gillespie’s eyes, and laughed himself, enjoying his own pomposity and yet happy enough to puncture it.

‘It’s my city. It belongs to me. Every New Yorker feels like that.’

Over dinner the talk turned to families. Here Dominic Carroll seemed more reticent. He had sons, grown-up sons, but no grandchildren yet. He didn’t say much about his sons, for a man of such far-ranging enthusiasms, but it was enough to tell Stefan that the American wasn’t as close to them as he wished. Somewhere in there was a failure he didn’t want to talk about.

He let Stefan talk more now, and clearly he could listen too when he wanted to, or when the topic of conversation wasn’t so easy. Details of Stefan’s life on the farm at Kilranelagh absorbed him and amused him, but it was when he told him about Maeve that something changed. Stefan retold the story of his wife’s death, six years ago, in the matter-of-fact way he always did. It was simply part of who he was. The American listened intently, then reached out his hands and clasped Stefan’s across the table. By now Stefan had had a bit to drink himself; his acquaintance was ahead of him. Carroll shook his head sadly, knowingly. He had found a bond between them. He was a sentimental man; sometimes sentiments shared were a kind of friendship for him.

‘My wife died when my eldest was thirteen. It wasn’t so unexpected. She’d been ill a long time, and however much money you’ve got, when they can’t do anything, it’s no use to you. You keep thinking you’ll find a doctor who knows the cure, if only you look enough and pay enough. But you can’t pay your way out of God’s decisions. You can’t pray your way out either.’

As he said the last words he crossed himself.

They walked back to their seats from the dining room with glasses of brandy, quieter than they’d come. Stefan had no desire to continue talking about the past; it was enough to say it. But the American wouldn’t let it go.

‘You’ve never remarried?’ he asked as they sat down.

‘No.’

‘You’re still a young man.’

‘I’m not avoiding it. It’s just something that hasn’t happened.’

‘You should count your blessings,’ said the American. It was an abrupt change of tone. Where his words had shown sympathy, consideration, shared understanding, there was a surprising edge now, something almost bitter. He looked away, staring at the window. It was dark outside now; all he was staring at was the black hole that was the night sky. ‘You should be careful. It was the biggest mistake of my life. If you want sex, you can buy it. You can buy as much as you want. But if you think you can replace the one love you ever had, if you think you can even come close, forget it.’

Stefan didn’t reply. The new tone of voice had unsettled him. It contained an appeal to an intimacy he didn’t want and didn’t feel he liked very much. Whatever the man was talking about it was his and his alone.

For a moment the American said nothing either. He seemed to realise that he had taken a direction he shouldn’t have done and had revealed more of himself than he was comfortable with. He looked up and smiled again. ‘That’s the trouble with a journey like this. Nothing to do but drink and they chuck it at you like there’s no tomorrow.’

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.