Sayfa sayısı 990 sayfa

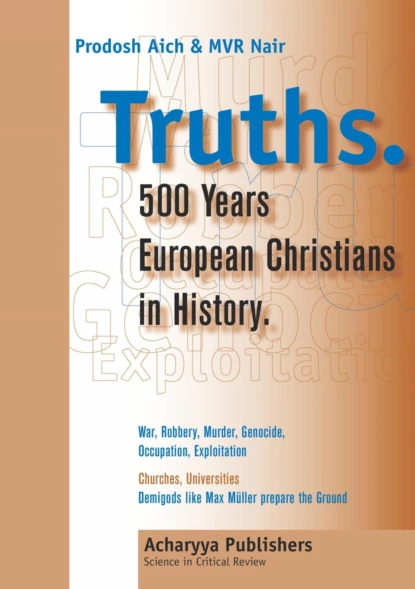

Kitap hakkında

We are what we know. We know what is handed down. Our daily life is organised by «historical narrations». Universally. To judge over the validity of «historical narrations» and of history, we must know all about those narrators of history. Today, and during the last two centuries, all narrators of history are educated in institutions created by European Christians. They narrate history incoherently though the history all over is coherent and interdependent.

The libraries are flooded by incoherent deliberations and with books that are copied and pasted from other books.

This is more so since the rise of the Ottoman Empire, since the blockade of the land route and beginning of search for a sea route to India, and all that has followed thereafter until our days. Why do they narrate incoherently though historical developments are coherent and interdependent by its nature? Why do they copy and paste and duplicate?

To judge over the validity of «historical narrations» in their books, the authors of this book search and investigate into the acquired qualifications and «careers» of all main narrators of this history. The search is based on primary documents. The result of this search is thrilling, mysterious and stunning. We are fed by books that are based on secondary sources. These books are mere propaganda, which should be stored in «bad libraries».

The result of this search has banged on the Pandora's Box and it is open now.