Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

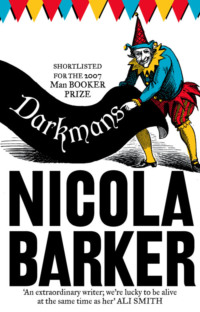

Kitabı oku: «Darkmans», sayfa 5

FOUR

An entry-phone engineer was taking what Kane could only (in all detachment and impartiality) call ‘an obscene amount of interest’ in Kelly’s thigh area. She was collapsed on Kane’s front step, both her legs stretched out stiffly in front of her, drinking from a flask of coffee and eating a Mars Bar (pulling back her lips as she bit down on it, almost in horror – like a donkey taking a Polo Mint from a suspicious-seeming stranger). He was crouched over her and gently massaging her upper knee as Kane drew closer.

Kane was not happy. His rage had two, distinct constituents. The first: simply that she was there (he was tired. He had dumped her. She was a pest). The second, that she was flirting. And this other man (his rival; a young man, looked Italian) had his filthy hands pretty much everywhere.

Kelly didn’t notice Kane until he was almost upon them. When she did, she let out a small squawk and dropped the chocolate bar on to her lap (as though Kane was the caustic battle-axe in charge of her slimming club). The Italian glanced up (blankly, momentarily) then returned his full attention to her thigh (it was an appealing thigh. Even Kane knew that).

‘How cosy…’ Kane murmured, affably (brandishing his finely wrought shield of charm before him).

‘Oh Fuck.’ Kelly seemed mortified, almost frightened. ‘This ain’t…it’s just…I fell off the wall and I…’

Kane was so unimpressed by the calibre of her excuse that he didn’t even bother to let her finish it. ‘Fell off the wall? How awful for you.’ He smiled, falsely.

She grimaced. ‘I was waitin’ on Beede. I had a special package for him. The gate was locked…’

Kane seemed quite riveted by this story. ‘The gate was locked, you say? That gate?’ He pointed behind him, towards the open gate. ‘How strange…And you were waiting for Beede? The Beede? Daniel Beede?’ ‘It fuckin’ was,’ she almost squealed, ‘I swear…’

‘Hmmn. A special package…’ Kane mused.

Kelly looked down, then around her, in a sudden panic. ‘Oh shit. Where is the fuckin’ thing?’

Kane rolled his eyes. Kelly didn’t even notice. She was still looking around for the brown envelope, visibly alarmed by its absence. ‘I had a package. Some black girl gave it me. Cross my heart…’

Kane reached out his foot and gently poked the crouching Italian with it. ‘Excuse me,’ he said sweetly. ‘May I interrupt you for a moment…?’

The Italian turned, sharply (still crouching) and raised the flat of his hand. ‘No,’ he said (in his threadbare English), ‘get loss.’

He wasn’t Italian. He had a heavy accent (mid-European, maybe an Arab, maybe Romanian). He was crazy-looking, like a sallow Frankie Dettori on some kind of growth hormone. Kane carefully reconsidered booting him for a second time. He was smallish, and thin, but the veins stood out on his fists like worm-casts.

Kelly struggled to get up.

‘Oh bollocks,’ she was muttering, ‘I lost Beede’s package. I’m in so much fuckin’ shit…’

‘What the hell are you doing?!’ the Romanian bellowed (and in his indigenous tongue, so it was just a stream of crazy babble to the both of them), then, ‘You,’ he continued, more haltingly (giving Kelly a firm glare), ‘jus’ stay! Okay?’

Kelly fell down again, shocked.

‘Wow.’ Kane took a small step back, as if the Romanian was a complex work of modernist art, best appreciated at a distance of several paces. ‘This guy’s a real gem, Kell. How on earth’d you hook up with him?’

‘I already told you,’ Kelly snapped, ‘I was waitin’ on Beede…’

‘Enough.’ Kane raised his hand in a gesture of weary compliance. ‘I give in. Do what you like. I’m knackered. My head’s totally mashed. Just shift out of my way, will you?’

He touched his fingers to his pounding temples.

The Romanian did not move. Kane tapped him on the shoulder. ‘I said just shift…’

The Romanian sprang around. ‘What are you?’ he demanded. ‘Some kind of imbecile?’ Then, ‘You! Go!’ he insisted, flapping Kane away as if he were some kind of vile bluebottle.

‘Go where?’ Kane tapped his index finger against his own chest. ‘This is where I live, you moron. This is my home.’

Kelly attempted to struggle up again.

The Romanian turned – ‘Idiot girl!’ – and firmly pushed her back down.

‘Ow!’ she expostulated, plaintively, as her bony arse made contact with the stone step.

At the sight of the Romanian manhandling Kelly, Kane completely lost it. He grabbed him by the shoulders – as if to spin him around again – but the Romanian was already moving smoothly of his own volition, and as he turned, his right fist turned with him. He punched Kane in the chest with it, then followed through with a hard left to his gut. They were powerful punches.

Kane doubled over with an embarrassing squeak. He saw the Romanian starting to lift his knee, then hesitating, as if re-considering delivering him a swift kick to the groin area (although it was still very obvious – even to him – that if the Romanian had seriously wanted to finish him off, he probably already would’ve. Those were amazing punches for a man of his stature – he was 5' 5" at a push).

Kane remained down for a few seconds (catching his breath, consolidating, thinking this all over), before his watering eyes finally settled on the steaming coffee Thermos (Ye Gods! A gift!), and, quick as a flash, he’d grabbed it, straightened up, and thrown the contents into the Romanian’s face.

The Romanian screamed. Kelly screamed (she was splattered, and the Romanian staggered sideways, accidentally knocking into her). Kane dropped the Thermos and heard the glass break inside of it (he took an active – almost adolescent – pleasure in the sound of its fracturing).

The Thermos had been open for some minutes and the coffee wasn’t exactly boiling, but it was hot enough. The Romanian was scalded, yet seemed far more concerned by the damage to his clothing. He was hopping mad.

‘This is my work shirt!’ he yelled, pulling the still-steaming fabric away from his hairy chest, gesticulating wildly. ‘You have ruined me!’

Kane suddenly started laughing. It was a hoarse laugh (he was winded). He pointed, weakly, at the ruined shirt (it was hardly the most glamorous-looking garment he’d ever laid eyes upon). The Romanian, meanwhile, had noticed his damaged Thermos. He snatched it up from the paving, almost howling.

‘My Thermos!’ he wailed (his pronunciation of the brand-name was – even to Kane’s ears – rather endearing). ‘What have you done?’

At this point a second man arrived; another entry-phone engineer, potentially the Romanian’s senior. He had Kelly’s two lurchers with him.

‘What’s going on?’ he asked the Romanian. The Romanian didn’t answer. Instead he took the Thermos – his knuckles white with fury – and threw it, violently, against the nearest windowpane. The window – it was a large, double-glazed one – chipped but did not shatter.

Even so, the second entry-phone man was visibly alarmed by this display. ‘Gaffar,’ he gasped, ‘are you off your fuckin’ head?!’

Gaffar stood his ground, his arms at his sides, breathing heavily (like the Invisible Hulk, transforming), his fists clenching and unclenching (‘the glass hasn’t shattered, dammit’ – his eyes were screaming – ‘so now I might be obliged to hospitalise somebody’). ‘That’s not even my window,’ Kane said, still chuckling, still limply pointing, like everything was a joke to him.

The second engineer glanced down at Kelly. ‘You all right there, love?’

Kelly nodded. Her eyes were closed now. She was resting her head against the door. Her face was very pale. One of the lurchers nuzzled her open hand. At its tender ministrations she emitted a gentle groan.

In the midst of all his hilarity, it finally dawned on Kane that she might not actually be bullshitting him about the fall. Had she fallen? He peered down at her, properly. He blinked (it was almost as though he hadn’t seen her there before –

Kelly?).

His mirth evaporated. A shattered piece of shin-bone was poking out – like a discarded lolly stick – through the tight, smooth flesh just underneath her knee. The lower half of her leg was purpling and swollen to almost twice its normal proportions. Her trainer was off (lying on the ground nearby, next to her slightly mangled-looking Nokia). If her foot was a balloon, then it’d been pumped too full of air (looked like some kind of zeppelin sent up to advertise a discount shoe-store; or one of those themed lilos which kids loved to bob around upon, in the hotel pool, on holiday).

It was gruesome. As a boy Kane suddenly remembered shoving a piece of driftwood into the heart of a beached-up, blue-white jelly-fish (to see if it was alive, to see how it would react). That was her leg – what it reminded him of –

Christ –

What a cruel child I was

He glanced over at the Romanian. The Romanian was standing exactly as before (arms down, fists clenched, breathing, breathing). His cheeks were wet – were shiny – with remnants of the coffee. In the distance Kane picked out the insistent bray of an ambulance –

Hee-haw!

Hee-haw!

Oh shit.

If the Romanian had punched him again – right there, right then: square in the face – he would’ve considered it an act of the most extreme beneficence.

His full name was Gaffar Celik and he wasn’t Romanian. He was a Kurd. He had just turned twenty-four. He was born in a poor town called Silopi, in Turkey, on the Iraqi border. His father had died – when Gaffar was only three – working as a Village Guard in a private army under the control of a Kurdish feudal lord. His mother had then taken them eastward (Gaffar, and his younger brother), first to Marlin (to stay with her widowed father), then on (when he passed) to be with her sister, in the beautiful mountainous village of Hasankeyf.

Hasankeyf was a kind of tabernacle to Kurdish culture (40 miles from Batman, straddling the Tigris River), and the sister was married to a man whose paternal line had found gainful employment for over twelve generations guiding tourists around the ancient sights there (the legendary caves, the remains of the old bridge, the magnificent obelisk, the beautiful, stone archway).

But few people visited them any more. The Turkish government had plans to flood the town as part of the Llisu Dam project, and so, gradually, one by one, the tour operators had wiped them from the cultural map (the south east had always been a difficult area). The decision – they insisted – was in no way political (to systematically flood all significant Kurdish landmarks? But what, they asked gently, was remotely contentious in that?).

Sometimes Gaffar felt like they were already submerged (there just wasn’t actually any water, yet), that they had been abandoned, betrayed, cut off. But he was not bitter (had no time for bitterness). He merely felt a dreamy nostalgia (for a non-existent future), coupled with a tender, almost poignant, regret.

Occasionally – and with scant warning – things could turn nasty. Battalions of Turkish soldiers would suddenly descend upon them, en masse, and burn down people’s homes (frighten them, move them on, accuse them of insurrection, of supporting the PKK and the Kurdish Revolution). Gaffar’s family were just one among many (the working estimation stood at 70,000) to be methodically oppressed (and displaced) in this way. Eventually it all got too much and they fled north, to Diyarbakir: Town of the Black Walls, where – for a short while, at least – they felt a little more secure.

Gaffar’s mother was a devout woman (especially since his father’s passing. You might almost think – Gaffar sometimes thought – that she was ‘making up’ for something). She was a follower of the Alexi Sect (Alexi was Mohammed’s brother-in-law; they were Shi’i, and persecuted – for radicalism – by the Sunni majority). Gaffar gave every appearance of conforming to this belief system. He had an actual, a palpable genius for pretending. Pretence was an essential part of his inheritance, of his pathology. He was proud of his duplicity (he didn’t have much, but at least he had this; he owned it. It was his).

There was a secret, you see, about his father – something shameful and unspeakable – which, even when he was alive, they only talked about in whispers. And now that he was gone, it was either never mentioned or hotly denied. But it was still true, nonetheless.

His father had been a Dawasin, one of the Yezidis; the oldest and most singular of all the Kurdish tribes; a reclusive, secretive, clannish people who worshiped Malik Taus, the Peacock Angel. They believed that they were the last remaining direct descendants of Adam’s line, that their race (and their race alone) was unbesmirched by the sins of Eve. They were pure (this was part of their patrimony), but they were not ‘of the Book’ (at least, not formally), and so, even amongst Kurds, they were both feared and despised.

Gaffar’s father had been born in Sinjar, on the Syrian/Iraqi border (it was the Kurdish lot to be born on the edge of things, the perimeter; to be squeezed into the outer reaches; at worst to be persecuted, at best loathed and ignored). In 1975 the Dawasin in that area had been forcibly evicted from their land and placed into collectives.

Times were hard. He had drifted to Baghdad, searching for work. He’d left a wife and a daughter behind him, staying away – out of desperation (or so he claimed) – for many months in conjunction. In Yezidi culture absence was a crime of excommunicable proportions. And there was no coming back from it. So after a while, he didn’t even try. His soul was lost from that point onward.

As if to underline this fact, categorically, he journeyed north, to Irbil, and became a denizen of the legendary Sheikhallah Bazaar, where he hired himself out as muscle in the trade of drugs, fake passports and illegal arms. He moved to Turkey on the back of his successes, changed his name (stole ‘Celik’ from a local mayor), converted to Islam and married Gaffar’s mother.

He’d wanted (he claimed) to leave his former life behind. He even said he’d seen Jonah (Yunus) in a vision, where the whale was not a sea creature, but an enormous tent (a living thing, somehow, with ribs and teeth and organs), and it was crammed – full-to-bursting – with people he’d known in the past (his old friends, his enemies, his compatriots), and they were all slowly suffocating. But his own chest was full of air (like he was the whale, or the lungs, or something), and Jonah, on observing this fact, reached out his hand to him, and they walked clear – clear of the tent, of the bazaar – into a world beyond, into a promised land.

An epiphany.

Or this was the mythology. The truth was much simpler. Things didn’t actually change all that much in Turkey (I mean the Kurds were persecuted everywhere, weren’t they?). The fabric of his life remained virtually identical. He’d simply crossed over (or turned inside out, like a polythene bag). He was on the other side, now, but the leap he’d made wasn’t gargantuan (like Jonah’s whale), and it wasn’t so much moral (or spiritual) as geographical.

He remained a soldier (but now paid by the state). The Guard were universally loathed. They were cruel and merciless. Some were just desperate, others, crass opportunists. Gaffar’s father was ruthless, but not actively sadistic. He dispatched his duties efficiently. He took the occasional back-hander. He still thought like a traitor. And when he died (suddenly, on a landmine) his reputation was a distinguished one. He’d been fearless and brave and single-minded. He’d conformed. He’d fitted in. He was remembered by his compadres as an honourable man.

Gaffar sometimes wondered where his soul had gone (I mean which of the deities he’d served was the more forgiving, the more powerful?). It was a telling thought: but weren’t all true nomads at their happiest in limbo?

Was God actually aware of that fact?

As he grew older it became increasingly apparent that Gaffar had fighting in his genes (in his bones, which he broke, then re-set, then broke again). It wasn’t that he was angry (quite the opposite). His strength was rooted in his curious implacability.

From the tender age of twelve he fought for money. He was a gambler. He could win or take a beating – he didn’t care which, particularly – so long as he was paid for it. He loved his family but he despised their life of grinding penury. He wasn’t political (and in Diyarbakir it was difficult not to be) and he did not actively support the PKK (let’s face it: when Ocalan was arrested, things actually got better: schools were opened, they could speak in their own tongue again…Ocalan was certainly a hero, but he was also a spitfire; didn’t really care where his stray bullets landed, just so long as he satisfied his overall agenda. He was single-minded – heroes often were – and matched the Turkish armed forces, blow for blow, in his ceaseless promulgation of violence and terror).

Politics were all well and good, Gaffar reasoned – ideals and such – but money was the language of progress. Money actually got you out of there; into the colourful world which flickered on the screens of the cable tvs in local cafes. Into freedom. Into Eden.

Gaffar was a bare-knuckle boxer, all over the region (developed quite a reputation, as he grew older, although eventually, inevitably, this began to work against him). The trick was in his stature. He was small, looked wiry. But underneath he was impregnable. His will was the iron rod in his spine which kept him standing (or told him the precise moment at which to fall). His will was indomitable. He was the God of his own insides.

But the whole world (alas) didn’t start and end upon his skin’s smooth surfaces. There was an outside (he could smell it, he could taste it. Sometimes it kicked or bit or bruised him). Outside all was chaos. And this chaotic outside – if it really wanted to – could suck you in.

There was no point resisting.

He got caught up (the hook went straight through his cheek) aged fourteen, fifteen, in the opposing currents of politics and corruption (dragged back and forth, aimlessly, between them). He hadn’t tried, it’d simply happened; he’d attracted attention, had become almost a talisman.

He hung around in the backwash for a while (rejected by family, embraced by the local mafia, imprisoned for a year), then finally – out of sheer desperation – he struck a deal (it was the gambler in him). He risked everything (made promises to God, crossed his fingers, held his breath, you name it). And it worked.

Six long hours in customs and he was spat out, with due ceremony, into the United Kingdom (thirty neat little bags of heroin killing time inside his colon).

King-dom?

They had a queen, they spoke English, they ate beefburgers and drank beer.

London. North London. Wood Green (no woods, not much greenery, but who cared? He was here. This was his big chance. His break for freedom…).

Hmmn

It’d looked better on the telly. And there was dubbing, too, in Turkey (or subtitles; hell, he wasn’t fussy).

When people spoke it sounded utterly foreign. He couldn’t react. He couldn’t respond. He was rendered dumb. It terrified him.

Language (not just violence, or poverty) was now his determinator. The people he needed to get away from were the only people he could communicate with (everybody important spoke Kurdish here).

It was a different world – he could certainly vouch for that – but it was still run by the same rules (the sky the same colour, the ground just as hard, his belly just as hungry, the same battles for territory). So he chugged on. Became a Bombacilar – a henchman for a gang in the Green Lanes area. Shelved his dreams of a boxing career. Supported Turkey in the football. Developed a taste for American lager.

Until everything crumbled – 22 January 2003. A vicious gang-fight on Green Lanes. A massacre. The accidental death of an innocent bystander. An armed swoop on a Haringey cafe. A police officer attacked with a kebab skewer. Illegal gambling. Nine arrests. Operation codename NARITA. Commanding officer Steve James and a friendly – a very friendly – interpreter. (Oh that friendly interpreter! The dire threats she’d made! And the bewildering promises!)

Her name was Marta. She was sixty-three years old, half-Cypriot and a widow, with a mixed degree in psychology and philosophy from Trent University –

Marta

She’d reached out her hand to him, and Gaffar had taken hold of it (it was a soft hand, smelled of hazelnut nougat and –

Mmmm

– Indian rose-water).

Marta, it soon transpired, was to be Gaffar’s Jonah (although the whale was not a tent this time, but the claustrophobic courtroom in which he’d calmly turned state’s evidence).

Gaffar – like his father before him – had niftily slipped the border. And on the other side?

Ash-ford?

What a clumsy word

So this was where his journey ended. This was where he’d sunk his anchor. This was his port, his haven, his harbour. This was where he disembarked: a crummy job, an old shirt, his faithful Thermos (a leaving present from a favourite aunt). Two weeks rent paid up in advance…

This –

Ah yes

– was his Brand New Start.

But only so long as he did Absolutely Nothing Wrong, Mate – D’ya hear?

Someone had to take custody of the two dogs, so Kane (having first glanced around him for any other likely candidates – bugger. Not a one) reluctantly agreed to shoulder the responsibility.

Once the ambulance had pulled off, he ushered them both inside. The big one was a little snappy, but they trotted into the narrow corridor gamely enough, turning at the foot of the stairs (leading up into Kane’s first-floor section of the flat) and gazing over at him, expectantly, as if awaiting further instructions.

Kane tried to move past them and the larger one growled –

Oh, really?

He tried again. This time it snarled, and the smaller one –

The little shit

– backed him up.

Right

Kane considered his options –

The pound?

Pest control?

The butcher?

Ten seconds later, there was a knock at the door. He answered, still musing. It was Gaffar. He was holding a large, brown envelope (which he’d discovered over by the wall) and a small, silver trainer. ‘This her,’ he said, proffering the trainer politely, like a down-at-heel Buttons in Cinderella.

‘Pardon?’

Kane really was quite exhausted.

‘These two items belong to your skinny whore,’ Gaffar reiterated.

‘Oh…yeah,’ Kane said, recognising Kelly’s distinctive footwear, and then (much to his horror) the brown envelope she’d mentioned previously. ‘Shit. This must be for Beede. Thanks…’

He took the two objects, tucked them under his arm, and was about to close the door (a symphony of growling promptly resuming behind him) when his conscience briefly pricked him and he paused. ‘So d’you get a roasting?’ he asked abruptly. ‘From your boss?’ ‘Eh?’

Kane mimed the throwing of the Thermos and then pointed to the chipped window.

‘Ahhh,’ Gaffar just shrugged, resignedly.

‘The chop?’

Kane made a chopping gesture.

No response.

He thought for a moment. ‘The axe?’

He made a dramatic slicing motion across his neck.

Gaffar’s eyebrows rose for a second, then he nodded. ‘Yeah, I’m screwed, but so what? I’m beyond caring, man. He thinks I’m a live-wire, huh? A troublemaker? Well he can stick his stupid opinions up his own arse. The bottom line is, I’ve had enough. I’m through. And that’s my decision. I’m master of my own destiny, see? I don’t care what he tells the damn authorities. He treats me like a slave, yeah? He pays like a…a cunt…yeah? I told him I could earn a better living out on the streets. I did that in Diyarbakir for an entire year. Lived like an animal, off my wits.’ Gaffar tapped the side of his head, meaningfully. ‘He’s a fool. An imbecile. I could devour his brains in one sitting and still feel ravenous.’ He paused for a moment, breathing heavily. ‘You’re right,’ he continued, vaingloriously, ‘I should slaughter his entire family. Steal his money. Steal his car. Get the hell out of here…’

As he spoke, Gaffar made a series of rather fetching little stabbing motions with an imaginary blade. On the final one, he symbolically disembowelled a toddler, then snatched some keys, which the toddler (rather mysteriously) appeared to be clutching.

Kane was scowling now, struggling to keep up with him. Gaffar observed his confusion (let it ride for a few seconds), and then, ‘I’m just joking,’ he exploded, with a loud cackle, slapping Kane jovially on the shoulder, ‘you big, fat, ugly American twat.’

He continued to grin at Kane. Kane smiled brightly back. ‘Correct me if I’m wrong,’ he said, ‘but I believe “American twat”,’ he drew a neat pair of speech marks in the air, ‘is actually part of an international vocabulary – a universal language – which we all share.’

Gaffar mused this over for a second, apparently unmoved. ‘Wow-wee,’ he finally murmured, dryly.

Kane sniggered (the man had balls, there was no getting round it).

‘You’re funny,’ he said eventually, ‘and you can take care of yourself. I respect that. Come on in. I’ll dig you out a spare shirt. We can smoke some ganja. Some weed, huh? Then I must get some fucking zeds or I’ll expire.’

‘Okay.’

Kane pulled the door wider. Gaffar slipped smoothly past him to a muted vibrato of snarling.

‘Just watch out for the…’ Kane glanced over his shoulder, worriedly. ‘Uh…’

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.