Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

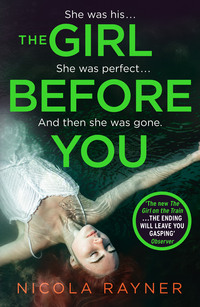

Kitabı oku: «The Girl Before You», sayfa 2

Naomi

It hasn’t happened for years. I’m in the Co-op staring at the fish, deciding between mackerel and cod, and the woman next to me in the cold section begins to fidget, interrupting my train of thought. She keeps glancing towards me as if she recognises me.

‘We’ve met before,’ she says at last.

She has a Geordie accent, is small and birdlike, with a nest of wiry hair and steel-rimmed glasses perched on the end of her nose.

‘I don’t think so,’ I say politely. I reach for the mackerel, put it in my basket and begin to walk away.

That is it for a moment. And then she remembers where she’s seen me.

‘I was there,’ she calls after me. ‘In St Anthony’s. The whole town … the whole town was looking for her.’

I turn back. I should have known from her accent.

‘One of my friends found the dress. Red, wasn’t it?’

I stand very still. ‘Green,’ I say.

‘I always thought it was red.’

‘No,’ I say. ‘That was her shoes.’

‘I worked that night at the ball.’ She takes a step towards me. ‘She kept coming to refill her glass. I felt dreadful when I heard she’d gone swimming afterwards. She never should, in that state.’

Everyone with even the slightest connection to Ruth’s death loves to tell their story. She takes another step. Her hair is in a dreadful state close up: coarse and dry. Her teeth are yellowing. Her breath smells faintly of fish. Such small things, matters of hygiene, make my stomach turn at the moment.

She says: ‘I’m so sorry. That’s all I wanted to say: I’m sorry. It must have been terrible.’

‘It was,’ I say.

‘I have a feeling,’ she continues in a low voice, ‘that in some way she’ll be back in your life before the year is out.’

‘Thank you.’ My voice sounds flat and strange. ‘But she’s gone.’

‘Well, maybe it’s just her spirit living on in you.’ She looks down at my belly, though I’m not showing yet. I’m only eight weeks in.

‘What do you mean?’

‘Like I said,’ she nods, ‘I have feelings about these things.’ She looks pleased with herself. ‘It’s a boy,’ she adds. ‘I know you and your partner would prefer a girl, but it’s a boy.’

I look at the door.

‘It’s not over,’ she says.

‘It’ll never be over,’ I hear myself reply. ‘She was my sister.’ The hiss of the first syllable, the rap of the second. Not a soft, gentle word, really, in the way it’s not a soft, gentle thing – which you would think it might be, if you didn’t have a sister. Before, in my other life, it was a noun I had used and heard thousands of times. ‘Is Ruth Walker your sister?’ ‘Your sister is in trouble again.’ ‘You must be clever, like your sister.’ Words, questions, phrases that made me irritated or proud but can never be used lightly or unthinkingly now. I’ve got to get out of here.

Walking away I’m careful not to look around, but I can feel her eyes on my back. My breath is trapped in my chest: a tense little pocket of air. I can’t always see panic approaching before it’s there, breathing down my neck. I place my basket on the floor as carefully as I can, and walk swiftly through the whirring cold section of the store and out through the sliding doors. As I glance back, I think she’s still there, standing like Lot’s wife, watching me go.

The frosty air hits my face like a slap, but it staves off the panic. I grasp a bike railing for a second to steady myself and tell myself firmly: Naomi, calm the fuck down. I cling on as the dizziness subsides. The cars slosh past on South Ealing Road, their headlights piercing the drizzle. The moment passes. I pull my hood up, tuck my chin into my chest and pace home. It’s not far, but the fresh air clears my head. And I think of Ruth.

She was fearless. I can never silence the small voice in me that reminds me something can go wrong – a flash, a premonition of an accident before it happens. My mother is the same – she would watch Ruth on her pony through splayed fingers and only I, standing next to her, would hear the sharp intake of breath as the animal approached a jump, see the quick smile on her face when they landed safely on the other side.

But Ruth loved jumping: the euphoria of leaving the ground, the purpose of it, the way the pony’s muscles would tense before taking off then stretch out as it soared. The knack was to lean forwards, not to try to contain it but to move with it, embrace the leap. I think she got that kind of thrill-seeking from our father; my mother and I have a different kind of courage.

She left her shoes behind. I gave them to her, her Dorothy slippers, red and sparkling. She was wearing them for luck that night. She placed them on the beach so neatly – which was rare for Ruth – with her handbag next to them. The police told us that often happens when people go missing.

A stinging wind picks up and, as I turn into our road, it really begins to pour. I run the last stretch, slapping my feet against the wet concrete. I think of the tiny being inside me and wonder if he or she can feel the impact as we run.

Carla has started cooking as I get home. The sweet, woody smell of cumin seeds fills the kitchen. It needs a good clean, I notice as I come in, but there’ll be time enough for that once I’m off work. I bury my face between Carla’s shoulder blades and she curls an arm behind her to hug me.

‘Did you get those bits?’

‘No. Sorry.’ I reach for Carla’s glass of red wine on the counter, breathe in its oaky fumes. ‘Something happened.’ I hesitate. ‘A self-styled psychic. One of those. She wanted to talk about Ruth.’

‘It’s been ages since you’ve had that sort of thing.’ Carla frowns as she stirs the popping seeds. ‘Did she know her?’

I take a small sip of wine. ‘No, not really. She was from St Anthony’s.’ I put the glass down, and try not to think of Ruth’s dress lying sodden and torn on the beach. ‘She could tell I was pregnant. We’re having a boy, apparently.’ I try to smile.

Carla looks down at my belly, puts a possessive hand over it. ‘That is weird. You really can’t tell yet.’

You would think, what with Carla being a therapist, that she would be familiar with the more esoteric aspects of human nature, but the fact is she’s the most down-to-earth person I know. We met in a group therapy session she was leading. It was instantaneous.

At the end of the first session, I waited to talk to her. She was shuffling our questionnaires into a blue folder. I hadn’t planned what I would say and, as I approached her, she didn’t look up at me at first, just said: ‘I think you ought to join another group.’

‘Really? I like your group,’ I said petulantly.

‘I think you know why.’

She looked up at me then. And she was right, I did. It was frightening falling for someone like that, after the last time.

‘I don’t know what to do about it,’ I whispered.

She laughed at me: ‘Well, after you’ve quit my group, we’ll go for a drink and take it from there.’

And, really, it was remarkably straightforward. I joined another group and we dated the British way, at the pub. I went back to her flat one afternoon, a few weeks after that first meeting, and never left.

That night, the dream returns. The one I always have. We are running through St Anthony’s, up one of the roads that winds from the sea. Ruth is calling: ‘Come on, slowcoach. Last one there’s a rotten egg.’ But she is always ahead of me, pushing further on until, eventually, she moves almost out of sight. I see a flash of her red shoes, her red hair disappearing around the corner. I hear her feet ringing out on the pavement just in front of me. And then I realise I can’t hear them any more. It is silent. And I start to shout: ‘Ruth? Ruth?’ There is just the sound of my own voice returning to me.

The panic begins then. And even though it is a dream, I can tell I have felt that particular sensation before. Because there’s more I need to ask her. There’s so much more to say.

The way I’m moving is less like running now, more like drifting, floating above the ground like a helium balloon. And as I turn the final corner, right at the top of town, I come across her red shoes on the pavement. They have been left there placed parallel, as if on purpose, as if they were a sign.

I wake gasping for air. The jolt of my waking stirs Carla. She murmurs something in her sleep, curves her body in a question mark around mine. It takes my eyes a few moments to adjust to the shadowed room. I lie in the dark, listening to Carla’s steady breathing, left with the sensation of the dream: that Ruth was just here; that she has only just gone. And, as always, at times like this – in the cold hours of night when I’ve woken with a jolt – the same old questions come flooding back. It’s as if they have been waiting for me.

What was on her mind as she got into the water? And did she think of me as she fought for her life? How it might feel to carry on living in the world without her? But there’s always one question that’s louder than the others, more insistent: was my sister in the water on her own? Or was there someone with her? Someone who placed her shoes and bag on the ground so neatly. Someone who wanted her gone.

Alice

Alice puts the last of the previous evening’s plates in the dishwasher. After a broken night, she finally drifted to sleep at dawn, missing George as he scrambled out of bed to get to a morning radio interview. He hasn’t really paused since his career change in the way she hoped he might. He’s on his phone the whole time, only half there in the evenings or the weekends, always in another place while he’s in the room with her.

She’s not much better. Often, the pair of them will sit together at the kitchen table at their laptops or side by side on the sofa tapping away on their own devices, which reminds her: she needs to email her newest client – the wife of one of George’s former colleagues. Alice frowns: George hadn’t been happy that she’d agreed to take on the case – a high-profile divorce between the Tory MP and his wife, a couple in their sixties who are separating after almost four decades of marriage. But she’s always got on well with the other woman, who, with her iron-straight bob and an unfussy, businesslike way of dressing, reminds Alice a little of herself.

As she fetches a cloth and wipes down the kitchen table, she notices that the uneasy feeling from yesterday has persisted. The episode on the train has a dreamlike quality as she reflects back. She thinks again of Ruth shouting in George’s face. Was that the party where they’d first got together? He’s always quite foggy about it – all the booze, no doubt – but Alice had thought she could recall it pretty clearly. And yet she hadn’t remembered the girl before – perhaps that had been a different party …

She’d wanted to impress George that night, for him to notice her. She’d dressed with him in mind. By that stage, of course, Christie had already snared Teddy – Alice smiles at the choice of the word ‘snared’ – but it’s one Christie, with her eye on Teddy’s castle in Scotland, might have used herself. Back then, the third-year boys had seemed like prizes to the freshers. She smirks at the thought now. Of course, George’s family has never had the sort of money that Teddy’s did – but certain doors would always be open to the Bells. George’s grandfather and his father were barristers. Perhaps that was why he’d ended up marrying a lawyer himself. They’re a family who make things happen – even his mother serves on the parish council in the Oxfordshire village where they live, where she held sway in her usual terrifying manner, no doubt. No wonder George became a politician.

His parents had backed him all the way, down to helping him to find a cottage when he was MP for Witney. The papers had mocked him as a mummy’s boy, but George hadn’t been bothered – ‘Everyone accepts help from their family,’ he’d say to her in private. There had even been a photo or two of his mother picking fluff off his collar in public, straightening his tie, that sort of thing, but George shook it off in the way a less charismatic man might not.

It’s not that George is cool – more that he genuinely doesn’t give two hoots about what people say. He could laugh off almost everything. Alice has the opposite problem, she thinks as she switches the kettle on: she cares too much about almost everything – her work, her clients, what people think. She’s learned over the years to care less, or hide it better, but the old worries that somehow she’s faked her way to success, that people might see through her, needle away at her. Her parents, both teachers, are very different from George’s. Her father, as the head of the Warwickshire state school she’d gone to, had an inner confidence, but he is a quiet person, self-contained. Alice catches him sometimes watching George as if trying to figure him out, while her mother, even after all these years, is jumpy around George’s family. She knocks things over, laughs too shrilly. Although she hates that she’s embarrassed by such things, Alice notices herself working extra-hard to smooth everything over when they’re all together – trying to overexplain or soften George’s quips, or to encourage her parents to relax more. Needless to say, George never sees any of this silent work going on, she thinks, with a flicker of anger.

The whistle of the kettle breaks this line of thought. Alice makes a cup of tea and takes it to the kitchen table. She opens her laptop and checks her email. There’s one from Elizabeth Gregory, the politician’s wife, saying how pleased she is that Alice is representing her. Her husband is having an affair with a young researcher on his team. The pair of them shared an eye-roll at that at their last meeting. ‘It’s not just the cliché of it,’ her client had confided. She’d closed her eyes – ‘It makes me sad for something I’ve lost, too. Something the pair of us have lost that he’s trying to get back without me.’

It was her sense of fairness that had drawn Alice to divorce law, that the quiet work of women should be recognised. Even in her own parents’ marriage there were inequalities. Her father could forge ahead with his career because her mother had looked after Alice and her sister. Often, her father had been home in time for bedtime stories, it’s true, but then that was the fun part of childcare – not the endless rounds of washing clothes, preparing meals, packing gym kits, remembering which child had which hobby on which days, driving around the countryside, and keeping their timetables and friendships and teachers in her head.

‘What makes me mad when I think of it now,’ Elizabeth had said, pausing to blow on her cup of coffee, ‘is the way he used to talk about me. If someone asked me a question about the children, he’d say, ‘Oh, I don’t deal with any of that. Ask my wife.’ The way he said it promoted me to the most important person in his life, but also made me, somehow, not important at all. How could I be absolutely crucial and yet as irrelevant to him as hired help? It’s hard to explain.’

She hadn’t had to: Alice had seen it enough in other marriages; though, in truth, it had always been different in her own. In his favour, George never demands too much of her in the way of housework or ironing. Their cleaner, Mrs T, looks after all that. Alice organises the Ocado deliveries, remembers birthdays, writes thank-you notes. What does George do? ‘I bring the fun,’ he would say. Not to mention their house in Notting Hill, which his parents had helped with. Distasteful as it is to think about it, there are advantages to being married to George, there’s no doubt about it.

Alice tries to remember more about the party where she’d seen Ruth, but not much more comes to her. She closes her eyes and tries again, recalls, on a separate occasion, walking into the college bar with her hand in George’s, and seeing Ruth and a friend of hers, Kat, exchange a glance, not a happy one, at the sight of them. They said a few words to each other and got up to go. As they passed George and Alice, Ruth looked as if she was about to say something, but Kat tugged at her sleeve: ‘Don’t.’

‘Do you know those girls?’ Alice had asked after they’d gone.

‘What girls?’ George asked, but then he’d seen Dan and bellowed a greeting at him. And that was that.

He and Dan were inseparable. They’d come up to St Anthony’s from Eton together with Teddy and a couple of others – a gang with a point to prove, perhaps, having not made it into Oxbridge. Alice had always been quite envious of the way George had started with a ready-made group. But of all his friends, Dan had been George’s closest. They made a funny pair – Dan was tall, slim and silent, George stout and loquacious. Dan’s looks would draw the girls to them but George’s charm would make them stay.

Alice had always liked George the most. A little shy herself, she’d found it hard to know what to say to Dan and he never gave much back. Whenever George popped to the bar and left them alone, Alice would find herself tongue-tied, unsure how to interact with Dan on her own. The thing was, she thinks now, it seemed that a part of him enjoyed how uneasy she was, as if it were a game.

When George came back from the bar, he’d say, ‘How are you chaps getting along?’

And once, Dan had said, ‘Oh, we’re getting along famously.’ It was a little piece of nastiness that only Alice could appreciate.

Another time, they’d gone out dancing and Alice, after a tipple too many, started mucking around with a pole, swinging around it sexily and giggling at George as she did.

George had grinned and blown her a kiss, but he’d been distracted by the time she returned to the table.

‘Great dancing,’ Dan had said in a tone that implied he meant quite the opposite. ‘Really sexy.’

Once or twice, when George was in one of his tender moods, in bed perhaps or after a few glasses of wine, Alice might ask: ‘Does Dan like me?’

And George would look completely puzzled and say: ‘Of course, you silly thing. Why would you ask a question like that?’

But it didn’t matter what he said, because Alice always knew, deep down, that Dan didn’t – that he’d never thought Alice was good enough for George. Maybe it was that she’d gone to a state school, or that her family didn’t have as much money as George’s; maybe it was that she didn’t have George’s natural wit, or the confidence of the people who’d grown up in the same social circles as the Etonians. Maybe, she thought on some days, it was because Dan had been in love with George.

She blinks at the laptop screen. No, that was ridiculous. Dan had liked girls. Of course, he had.

But there had been such a strong connection between them, as if they shared some kind of secret. Maybe even a secret related to Ruth Walker – to why she might have hated George enough to shout at him, to leave a room when he entered. Alice sighs. She’s not going to be able to concentrate on anything else unless she does some digging. She picks up her laptop and heads to George’s study.

Kat

October 1999

Dressed in black, Kat smudges her lipstick on her third cigarette. The rush of nicotine makes her feel light-headed, insubstantial. She had been so full of hope for university – had had a rather precise idea about the kind of life she was going to lead. That was why she had picked this wild town on the edge of Britain over a civilised place like London. She had packed a couple of bottles of champagne, nicked from her father’s wine cellar, and cigarettes and the Collected Works of Dorothy Parker – but she had been greeted at the gates by the freshers’ rep, a pale, gangly boy with wispy hair that stuck out in different directions. Not fanciable at all.

She could tell he wasn’t used to girls like Kat – not used to girls full stop – and it hadn’t taken much to make him blush into his tea, make his excuses and scuttle off back to his dusty textbooks. Kat had never been one for making an effort with people she couldn’t see the point of. It was something she had inherited from her father. Not a nice trait, she realised, but then her father wasn’t a very nice man.

But if she liked someone, it was another matter entirely, as if a light bulb had been switched on. It had been like that the other night in what passed for this town’s only nightclub. She’d met him a few drinks in, so she couldn’t remember exactly how things had started. There she had been, waiting by the bar, and he seemed to have appeared beside her. Messy hair, dark eyes, low voice. Soothing to be around, a measured way of speaking and holding himself. And she had felt a kind of certainty, a kind of excitement.

And admittedly, she’d had five, or maybe six, vodka cranberries at that stage, so the certainty could have just been an epiphany created by booze and a handsome face. But then she had woken up the next day early and surprisingly clear-headed, sure that something important had begun, and a couple of days later the feeling had barely shifted.

No one she’d asked knew who he was. It didn’t help that she couldn’t remember his name. He was a second year – she recalled that much – and he played the guitar in a band and could quote Dorothy Parker.

And now, at this party, there he is again and Kat, who is never nervous, is experiencing a fluttering feeling in her limbs. Strange how liking someone can distil into a single detail: the smell of his cologne, the feeling of his arm under your hand, the sound of his laugh. With this guy it’s his voice – low and calming – she can catch the cadence of it from where she is standing. He’s talking to a small bloke next to him, with a keen, ratty face. Kat looks at him steadily, waiting for him to glance at her in return so she can smile, or look away, and let it all begin.

But he doesn’t look at her, because he’s looking at someone else.

Kat has seen the girl before at other freshers’ events. She is wearing a long white dress – a bold choice for a redhead and a touch virginal for Kat’s tastes. There’s something knowingly Pre-Raphaelite about the combination. It calls to mind paintings of tragic heroines, tresses weighed heavy with water and flowers. Still, she has a lively, likeable face, but then, thinks Kat, putting out her cigarette and straightening her dress, before making her way to the messy-haired guy, so does she.

‘Hello again,’ she says.

‘Kat, isn’t it?’ he smiles. ‘This is Jerry.’ He jerks a thumb at the boy he’s standing next to.

‘Richard’s in love,’ says Jerry.

Richard. That was it. Kat tries to smile again and looks over at the redhead.

‘Shut up, Jerry.’ Richard stops looking at the girl and turns to Kat.

‘You can’t take your eyes off her.’ Jerry’s mouth twitches. ‘You know what they say about redheads?’

Kat doesn’t believe for a second that this boy knows anything about redheads – or girls, for that matter. The three of them watch as the girl lights her cigarette in a knowing way and makes her way to the drinks table.

‘Go and talk to her,’ Kat says quickly to Richard.

She doesn’t want him to – of course, she doesn’t want him to – but she will never be one of those women. A memory of her mother hovering around her father pops into her head – who holds onto a man’s sleeve, who begs him to stay.

Richard bites his lip. ‘Maybe later,’ he says quietly. ‘How are you?’

‘When you like someone, you should just try,’ says Kat, ignoring the question, aware of the irony. ‘Just say hello.’

He smiles. ‘Perhaps you’re right.’ He touches her arm to excuse himself. ‘Wish me luck.’

Kat watches Richard as he picks his way across the room. At one point, stuck behind a tight cluster of maths students who won’t make way for him, he glances back at Kat with what looks like a question in his eyes. She smiles brightly and gives him a thumbs-up. As he reaches the drinks table, the redhead is standing with her back to him, which is awkward – so difficult to approach someone like that: do you tap them on the back? Start a conversation with their shoulders? But Kat will never know how that conversation might have started, because there’s a sudden movement in the cluster around the drinks table, a gasp and, as if in slow motion, a glass of red wine slices through the air towards the girl’s white dress. There’s a shriek and the guy who has spilt the drink is moving towards her, all apologies and hands, trying to dab at the jagged stain with his handkerchief.

‘Oldest trick in the book,’ Jerry breathes next to her, looking towards the student with the handkerchief: a sturdy-looking chap with aquiline features and an air of unshakable confidence.

‘What?’

‘George Bell,’ says Jerry. As if that explained something in itself. ‘He’ll be saying, “Let’s get you out of those wet clothes.” Something like that.’

‘Right.’ Kat makes out the back of Richard’s head in the shifting crowd.

‘Classic George.’ Jerry smirks. ‘He’ll always pick the most beautiful girl in the room and do that sort of thing.’

Kat blinks, pushes a strand of hair behind her ear.

What is Richard doing in all this kerfuffle, as George passes the redhead a cloth, as he pours her another drink, as he lifts his hand, briefly, to wipe away a few drops, real or imagined, from the girl’s hair? There he is. Kat catches a glimpse of Richard’s face, pale and grimacing, as he turns back towards them.

‘What happened there?’ she asks.

‘George happened,’ he says in a low voice so Jerry won’t be able to hear. He looks into his drink.

Kat can catch the odd word of George’s plummy voice across the room. ‘Who’s he?’

‘He is’—Richard pauses for a moment as if to find the correct phrase—‘an unspeakable cunt.’

Kat, usually unshockable, blinks at the word. ‘Why?’ she wants to say.

She looks at the girl again, who glances over at them. She narrows her eyes slightly as if in recognition of something. Kat smiles tightly and wonders if Richard has noticed.

The moment passes. The girl seems to be getting ready to go somewhere with George. She picks up her bag and turns her face towards him to say something as they leave. Kat can’t hear what she says, but George laughs heartily and presses a casual hand into the small of her back.

Then, Kat would think later, if things had gone otherwise that night, that moment, everything might have been different. But, instead, she takes another sip of warm white wine and sees, from the corner of her eye, George’s group sashay out of the party, the outline of a white dress as they move away.

And though it should be a relief, though things should brighten, shift, now her rival has gone, that is not the case. She just can’t win Richard’s attention back, nor recapture the magic of the other night and all her usual tricks – a way of telling an anecdote, her hand on his arm, a certain sideways smile – fail to pique a reaction. Or maybe it’s her. It seems to Kat there’s a heaviness to everything she does tonight – the stories aren’t coming out right. The rhythm of how she tells them is wrong. Or the intonation. She can’t tell. But Richard and Jerry’s smiles are polite more than anything. Jerry’s glance darts around the room, while Richard keeps looking at the door. And even Kat’s thoughts drift to the girl in the white dress, the way she walked across the room like a dancer, the way she had caught Kat’s eye before she left.

Some girls had things easy, but Kat had always had to try. To be entertaining: that was the most important thing; that was something she’d learned from Dorothy Parker. And if nights like this made you feel sad and defeated, then you went to bed and woke up the next day and, generally, in Kat’s experience, the darkness would have shifted.

Eventually, Richard finishes his drink and slips away saying something about the library.

When it’s just the two of them, Jerry perks up. He moves closer to her when she speaks. His polite smiles become forced laughter. Occasionally he touches her, on the shoulder, her waist, as if testing something.

‘Where did Richard go again?’ Kat asks, anticipating another touch, stepping away, leaving his hand hanging for a moment in the space between them.

Jerry rolls his eyes. ‘I wouldn’t bother with Richard, if I were you,’ he says. ‘When he likes someone, that’s it.’

Kat looks down at the art deco cigarette case in her hand, her remaining cigarettes lined up like soldiers. It was a present from her father for her eighteenth birthday last year, but she suspects his latest wife, his third now, only seven years older than Kat, might have had something to do with it. Should she bother with another cigarette or not? The feeling of light-headedness is back.

‘That’s it,’ says Jerry again. ‘Richard won’t be swayed from his course.’

The engraving inside, though, that must have been her father: ‘Faute De Mieux’ by Dorothy Parker. He was a huge fan, too – sometimes it was the only thing that Kat could be really sure they shared.

‘It’s funny,’ she says, snapping the case shut. ‘I’m just the same.’

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.