Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

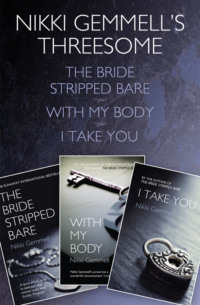

Kitabı oku: «Nikki Gemmell’s Threesome: The Bride Stripped Bare, With the Body, I Take You», sayfa 4

Lesson 23

the importance of needlework and knitting

You have a book given to you by your grandfather that’s a delicious catalogue of unseemly thoughts:

That a wife should take another man if her husband is disappointing in the sack.

That a woman’s badness is better than a man’s goodness.

That women are more valiant than men.

That Adam was more sinful than Eve.

It was written anonymously, in 1603. It’s scarcely bigger than the palm of your hand. The paper is made of rag, not wood pulp, and the pages crackle with brittleness as they’re turned. You love that sound, it’s like the first lickings of a flame taking hold. The book is tided A Treatise proveinge by sundrie reasons a Woemans worth and its words were contained once by two little locks that at some point have been snapped off. It smells of confinement and secret things.

You imagine a chaste and good wife writing secretly, gleefully, late at night and in the long hours of the afternoon. A beautiful, decorative border of red and black ink hems each page. It’s a fascinating, disobedient labour of love. You wear cotton gloves to open it. You’ll never sell it.

It’s been in the family for generations. A rumour persists that the author’s skeleton was found in some cupboard under a staircase, that she’d been locked into it after her husband discovered her book. Your father told you stories of her scrabbling at a door and crying out and of her despairing nail marks gouged into the wood, but you suspect the reality is much more prosaic: that your great-grandfather acquired the book at auction, as a curiosity, and it may even have been written by a man, as an enigmatic joke.

Cole calls it The Heirloom, or alternatively, The Scary Book. He teases that he’ll toss it in the bin if you’re naughty, or lock you in the cupboard and never let you out. You love all this banter between you; he makes you laugh so much. You never see any irony in it. He calls the bits and pieces of your father’s furniture dotted about the flat The Ruins. And you, affectionately, The Old Boot. It never fails to get a rise out of you; Cole loves seeing that.

Lesson 24

the chief causes of the weak health of women are silence, stillness and stays; therefore learn to sing and dance, and never wear tight stays

The hanging sky. The air smelling of the sea. You don’t even need an umbrella as you lie on a sunlounger next to the pool. The breeze blowing in from the desert plays havoc with your Herald Tribune and you give up and watch the people around you, you’re more interested in the women’s bodies than the men’s, all women are, Theo has said and she’s right. You remember exactly her body when she was sixteen, the short waist and long legs and moles on her chest, and yet you can hardly remember the men you’ve slept with, any of them. The names or the bodies, only the faces, just, and the shape, vaguely, of penises, whether they were long, or too thick—God, you dreaded that, the grate of it.

The attendant presents you with a gin and tonic on a silver tray and you look around, startled. The man from the lobby smiles his beautiful boy smile from a distant sunlounger and you lower your head and do nothing more, don’t drink, don’t look, you’re confused and you know that Theo’d be cross at this, a missed opportunity.

Theo. Such a pirate of a woman, with a different energy to her. She’s thirsty and needs to drink, it’s in the way she walks and listens and leans and talks. She’s a woman who overlives, she has so much life in her, it shines under her skin. Does that mean you underlive? Your heart dips with panic as if a cloud has skimmed across it.

You look across to the man on the sunlounger now reading his Tribune and tilt back your head and close your eyes. You’re living your days at the moment how a sheep grazes, meandering, not engaged with anything much. And yet, and yet, you’d never wish for Theo’s kind of existence. She’s so free, so answerable to no one that she’s lost.

The sky deepens, bathers pack up their suntan lotion and one by one leave, the baked breeze stiffens and umbrellas are snapped down for fear they’ll cartwheel away. You slip into the pool. The water’s ruffled like corrugated iron. You’re the only one in it and you slide through the coolness and strike out for the first time in years, feel unused muscles creaking into working order and think of your mother and her strong, confident hands and the ribbons of water when you were seven. You’ve no family consistently around you now, your friends have become your closest relations: Cole, of course, and Theo, your sister of sorts, although at times there’s the intensity of lovers between you.

It’s her birthday today, you must call.

You smile as you pull your body through the water and at the end of the pool look up to great plumes of ochre dust blown in from the desert; it’s as if the dusk is being hurried centre stage. The attendants move with crisp deliberation now, clearing towels and cushions from chairs. Most people have gone. Palm trees toss their branches like the manes of recalcitrant ponies, twigs and leaves blow into the pool and you climb out of the water at the first fat splats. You smell the earth opening up as if it’s breathing, feel the thundery day sparking you alive and you lift your chin to it and inhale deep and gather up, reluctantly, your sun gear. You pass the man from the lobby, still reading valiantly. He looks up at you.

You don’t look at him. You walk inside, to your husband, a fluttery anticipation within you.

Lesson 25

lending is, as a rule, the greatest unkindness we can be guilty of, unless we can give

The elderly man who looks after the roses lets you into the room, bowing and smiling his gentle smile. He’s presented you, gallantly, with a single stem and you’ve accepted it graciously; it’s a game played with some seriousness. The petals are deep red, almost black, and you plunge your nose into their oddness: it’s a wild plump garden scent from your childhood, not the tight manufactured whiff from the buds you buy at the supermarket. You enter the room soundlessly, you’ll surprise Cole, he’ll throw you on the bed and make you laugh and kiss you in his special way and you’ll melt, succumb, even though you’re still menstruating. Sexy sex, hmm, grubby, spontaneous, impolite kind of sex, you haven’t done that for years and all of a sudden it seems necessary. The room’s dim from the darkening sky and you can taste the thunder outside and lift your chin to it. Cole’s on the phone. You’re cross, he shouldn’t be doing any work during this trip, he promised.

I can’t wait to get out of here, it’s driving me crazy, the heat, and he says this in his special voice, your voice, but there’s a playfulness, a lightness, it’s a tone you haven’t heard for so long. All she wants to do is run off to the markets and have rides in those fucking carts, I can’t stand it, I get so bored, I just want to relax. He pauses. Diz, Diz, no, you can’t. He chuckles. Yeah, me too. I’ll see you soon, thank God.

Lesson 26

air ventilation oxygen

You’re very still. You walk past Cole without looking at him. You walk through the french doors, to the veranda, and sit, very carefully, on the wicker chair.

Your thudding heart, your thudding heart.

You sit for a very long time, soundlessly, into the rich silence after the storm. At the end of it the sun feebles out and nothing has cooled down, nothing, it is as hot as it ever was.

II

My soul waiteth on thou more than they that watch for the morning,

I say more than they that watch for the morning.

Psalm 130

Lesson 27

there ought to be no cesspool attached to the dwelling

The Monday after the return from Marrakech. A cafe in Soho, alone. An old London chophouse selling beans on toast and Tetley’s tea in stainless-steel pots, the menu padded and plastic covered. Reading the paper but not.

Like you are skinned.

I can’t explain it, he has said, reddening, every time. When you’ve asked him again and again. You’re overreacting, he has said. She’s a friend, our friend, we’d just have a drink now and then. And then he stops.

As if what he wants to say can never be said, as if it will never be prised out. But you will not let up.

Just a friend. Uh huh.

You sit back at his words, you fold your arms. At his explanations that are scattered bits of bone, that are never enough.

You haunt the cafe in Soho. Want to crawl away from the world, curl up; want to shrink from the summery lightness in the air, the flirty pink on the girls in the streets.

Within this God-tossed time he’s never stopped telling you he loves you but you’ve no desire to listen any more. For the relationship has been doused in a cold shower and you are chilled to the bone with the shock.

Just a friend. Uh huh.

You will not let up.

Now it’s a week since you’ve known; now two. Everything is changed and nothing is changed, you’re reading the paper but not. You prefer this cafe in Soho over the American coffee chains that seem of late to be everywhere, despite Cole’s certain horror at the choice. Before, you’d let his likes and dislikes shape the movement of your day, even when he wasn’t with you. But you’re disobedient often now, in little ways. For realisation of the affair has snapped upon you as fast as a rabbit trap, and you are exiled from your marriage and home and life.

The elderly man behind the till senses something of all this; he smiles warmly in greeting, now, and hands you your cup of tea without waiting to be asked.

We’d. just. have, a drink, now. and. then. All right?

I don’t believe you. I’m sorry, I can’t.

It’s the truth, I am so sick of telling you that.

I don’t believe you. I can’t.

Your hands hover, frozen, by your head. Your fingers are clawed, your knuckles are bone-white. You have turned into someone else. You do not recognise the voice.

Day after day you shelter in this cafe in London’s red light district. It’s a small indication of something that’s burst within you. You’re not sure why you’ve picked this place, you never go to cafes or restaurants by yourself, it’s too exposing. All you know is that the two people closest to you have gone from your heart, it’s flinched shut. And it’s only as you spread your newspaper and pour the milk into your tea that you feel the tin foil ball, tight within you, unfurling. No one would guess just by looking at you, the quiet, suburban housewife, that recently in a hotel room in Marrakech your entire future had been crushed by a single blow from a rifle butt.

And all that’s left is rawness, too deep for tears.

She’s a friend, just a friend, it’s all he can ever say and in this Soho cafe, the third week of your purgatory, your teacup is slammed down. So hard, the saucer cracks.

Lesson 28

disease is the punishment of outraged nature

A month after your return from Marrakech. A stagnation sludges up. You’re not bored or angry but stopped; nothing engages, nothing interests, you’re at a loss over what to do next, with the next hour and with all the days of your life. Sleep is the short-term solution. London’s good for that. Its light is milky, filtered, unlike the light from your childhood that stole through the shutters in bold blocks in the morning, nudging you awake and pushing you out. The sky in London is like the water-bowed ceiling of an old house and you doze whole mornings away now and on waking there’s a panicky sickness in your gut. Then you walk the streets, seeing but not seeing, husked.

Selfridges lures you inside, its sleek promise. You haven’t been here for so long, you used to trawl it with Theo, she’d always have you trying on things you didn’t want. You browse the accessories counters. Buy six rings. Space them out on your fingers, blurring your marital status; your engagement and weddings rings are swamped and you smile as you stretch out your hand.

But then it’s back, his voice. It always comes back. The tone of it as he spoke to her on the phone. It’s not so much the thought of them physically together, it’s the intimacy in his voice. It wasn’t until you overheard it in the hotel room that you realised how long it’d been since you had heard it. And you missed it, violently so.

Your voice.

Your teeth are clenched as you walk to the tube and with effort you soften your jaw and rub at your brow, at a new wrinkle between your eyes. At the end of each night you knead it, your fingertips dipped in the chilly whiteness of Vitamin E cream. Beyond you, the flat ticks. The rooms are dark except for the bedroom. Cole’s away a lot now, working late; that’s his excuse. There’s no light in the hallway to welcome him home. At the end of each night, seated at the dressing table, your fingertips prop your forehead like scaffolding. For it’s the long, long nights that defeat you.

When you are blown out like a candle.

Lesson 29

friends are too scarce to be got rid of on any terms if they be real friends

The buzzer, too loud, blares into your morning. You groan: you’re still in bed. The intercom’s broken, you’ll have to go down three flights of stairs and open the front door to find out who it is; in your old bathrobe, without your face.

Theo. Red lips and red shirt, the colour of blood. On her way to work.

You close the door. This is ridiculous, she says, come on, we need to talk. You lean your hands on the door with your arms outstretched. Can’t we just talk, she pleads. Her knocks become thumps, they vibrate through your palms. You straighten, walk up the stairs, do not look back; your fingers, trembling, at your mouth.

Theo’s betrayal is magnificent, astounding, incomprehensible. It’s her actions you can’t understand, not Cole’s. You always assumed she was the one person you’d have your whole life, not, perhaps, your mother or your husband. She’s a woman, she knows the rules. Men do not. You’re not interested in an excuse, nothing can put it right, for anything she says will be overwhelmed by the violence of the loyalty ruptured and your howling, pummelled heart.

You can’t bear to think of them together. You have no idea how Theo is with a man. How she operates, if she turns into someone else; if she changes her manner and voice. It’s a side of your girlfriends you’ve never intruded upon. All you know is that your husband is trapped in her hungry gravitational pull: his voice told you that.

As you were once. Theo was sloppy with your relationship—never turned up to dinner parties with a bottle of wine, never sent thank you cards, cancelled nights out at the last minute, was often late – but she was always forgiven for she made your hours luminous with the gift of her presence; as soon as you saw her all the irritation would be lost.

Now, she tries to contact you again and again but the phone’s hung up no matter how quickly she rams in talk, her e-mails are deleted unopened, her letters ripped. You’re good at cutting people off, it’s always been a skill, a small one but effective; making things neat, moving on. Theo will hate being ignored. It’s what she fears most. You feel a strange sense of power, the extreme passivity makes you strong; it’s how you can protest, it gives you a voice. Like, sometimes, with sex.

Lesson 30

old medicines should not be kept, as they are seldom wanted again and soon spoil

Cole needs you for a party. It’s hosted by a gallery owner with a painting that needs cleaning, a Venetian landscape by a pupil of Canaletto. Cole’s hungry for it; he suspects there’s something from the master hidden underneath. You don’t want to go. Don’t want to give him anything yet.

Please, Cole says.

I hate that kind of thing. You know that.

Simon likes you. I need this job.

You know the wife Cole wants for this. He’s told you before you’re good arm candy: everyone likes you, thinks you’re sweet, lovely, wants to chat with you, but it means the supreme achievement is that everyone is admiring of Cole, for he’s showing off a possession, like a car or a gold watch or a suit, and you’re flavouring people’s impressions that he’s a success. You’d loved it when he told you this: to be so prized. You’ve always brought out the best in each other in social situations. At parties your sentences lap over each other as you tell your old anecdotes, at dinners with friends your meals are absently shared, during your own dinner parties it’s a smooth double act of cooking and serving and clearing up. You’re both good at playing the married couple, you prop each other up.

Please, Cole says now.

All right. All right.

Your hand rests at your throat. You always give in, have done it your whole life; where does it come from, this stubborn need to be liked?

A mews house, not far from your flat. Simon is tall in the centre of the crowded room. He judges his success by his proximity to famous people, he name-drops a lot, he can’t be by himself. He likes you because you read show business gossip and respond, wide-eyed, to his talk. He’s in a relationship, fractiously, with a pop star from Dublin who had a good haircut and a summer Number One whose title you can never recall. She’s not at the party. There are no famous people at the party. Simon will be keenly disappointed. You look at all the guests darting eyes over shoulders, mid-conversation, checking out everyone else, it is as if the sole reason everyone is here is to see someone famous.

You want out.

You’re alone in a corner on a black leather couch that creaks like a saddle. There’s a lava lamp beside you. It’s no longer working. You’ve never been voracious about partying. You’re too good at blushing, and awkward silences, and saying something jarring and wrong. You’re not very accomplished with big groups, have always been more comfortable with one on one, the small magic you can work is always dissipated in a crowd. You look at the guests. Hate the thought of being single again, of meeting every man with intent. You redden in front of anyone you’re attracted to and have never grown out of it, your body often lets you down. You imagine Theo here with an admiration that hurts: see her sparkling in the centre of the room and poking her head into circles of talk and floating from group to group.

You’re wearing a black satin dress that has antique kimono panels through its bodice and you usually love this dress but tonight it’s wrong, you’re overdressed. You have to get back to your flat. You can’t walk home by yourself: there are two crack houses on your street and just last week a woman was stabbed. You need Cole. He’s in good form, he’s working the room; you wish he’d hurry up. You hate the feeling of entrapment you can get at parties, hate being reliant upon someone else for your means of escape. You’re stuck, in a black satin dress that tonight is too much.

Cole’s with Simon. Neither likes the other much but they keep in touch for they never know when the contact may be useful. They’re not talking about the Canaletto, anything but that: it’s not Cole’s way to be so blunt. There’s a lull in the talk and you stand and tell them, politely, you’re going home. You walk to the door. A hand is splayed across your lower back. There’s steel in it. It propels you to a balcony knotted with people and you shy away but the hand is still firm round your back.

I have to go home, you say, very low, very old.

I just need an address. Five minutes. OK?

You time it, then pull him out.

Cole and you have both won tonight but Cole has won more. He always wins the most.