Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

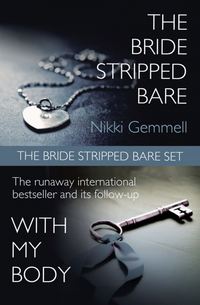

Kitabı oku: «The Bride Stripped Bare Set: The Bride Stripped Bare / With My Body», sayfa 2

Lesson 10

garments worn next to the skin are those which require frequent washing

Men you have slept with. What you remember the most:

The one who loved women.

The one who never took off his socks.

The one whose hands were so big they seemed to be in three places at once.

The one whose touch hummed, who seemed to know exactly what he was doing and stood out because of that. He seemed only to derive pleasure from the experience if you were, whereas none of the others seemed too fussed. He asked what your fantasies were but you didn’t have the courage to speak out. Back then, you’d never have the courage for that.

The one who sent you a polaroid of his very big cock.* But size means little to you, you don’t know why they go on about it. You much prefer a comfortable fit than a penis that’s too big; you don’t want to feel you’re being split apart.

The one who’d say take me as he came and groaned like he was doing a big shit.

The one who tickled you behind your knees and licked you on the face, who forced you to swallow his cum and rubbed it through your hair; who was aroused by all the things you didn’t like.

The one who said yes, when you asked him to marry you, half joking, half not, on a February the twenty-ninth. You’re embarrassed you had to ask Cole McCain. You wish he’d never mention it, but he does, in a teasing way, a lot.

*You’re more than happy to write the word cock; saying it aloud, however, is another matter. It even feels a little odd to say vagina but you’re not sure what else to use. You hate pussy, you don’t know any woman who says it, and as for cunt, you always think it’s used by men who don’t like women very much. You want some words that women have colonised for themselves; maybe they exist but you haven’t heard them yet. You can’t say down there for the rest of your life.

Lesson 11

a sacred and delicate reticence should always enwrap the pure and modest woman

Early morning.

A bird flaps into the room and you wake, panicked at the flittering above your head and run to the bathroom and slam the door, begging Cole to do something, quick. The bird’s swiftly gone. It hasn’t crashed wildly into mirrors or windows. You couldn’t bear that—you witnessed it once as a child, the droppings out of fright, the too-bright blood, the crazed thump, the shrill eye.

But now there’s just quiet hovering in the room. You step into it from the bathroom and kiss Cole on the tip of his nose. He envelopes you in his arms with a great calm of ownership and laughs: he likes you vulnerable. And to teach you, to introduce you to new things. You didn’t look closely at a penis until you were married, didn’t know what a circumcised one looked like. You wonder, now, how you could’ve had the partners you’ve had and never really looked. You always wanted the lights off quick because you never liked your body enough, and dived under the sheets, and felt it was rude to study a man’s anatomy too intently: you favoured eye contact and touch. Cole forced you to look, right at the start, he taught you to get close. He likes to direct your life, to guide it.

You let him think he is.

Lesson 12

it is our greatest happiness to be unselfish

Cole fell asleep inside you once. He laughs at the memory, finds it erotic and silly and comforting. The morning after, to soothe your indignation, he’d said that falling asleep inside a woman was a sign of true love.

What? Shaking your head as if rattling out a fly.

It means that the man’s truly comfortable with the woman, so comfortable that he can fall asleep in the process of making love to her. I could never do that to anyone else. Think yourself honoured, Lovely.

Hmm, you’d replied.

You love Cole in a way you haven’t loved before. Calmly. It glows like a candle rather than glitters. You love him even when he falls asleep in the process of making love to you. You’d never loved calmly before, in your twenties. That was the time of greedy love, full of exhilaration and terror, and when you said I love you you always felt stripped; there was no sense, ever, of love as a rescue. Sometimes, now, you wonder what happened to the intensity of your youth, when everything seemed so vivid and desperate and bright. Sometimes you imagine a varnisher’s hand whipping over the quietness of your life now and flooding it with brightness, combusting it, in a way, with light.

But Cole. When he enfolds you in his arm you feel his love running as quiet and strong and deep as an underground river right through you. He stills your agitation in the way a visit to Choral Evensong does, or a long swim after work. The bond between you seems so clear-headed: the marriage is not perfect, by any means, but you’re old enough now to know you cannot demand perfection from the gift of love. It’s a lot more than most people have. Like Theo.

Your dear, restless, vivid-hearted friend. Sometimes you feel a sharp envy at the sensuality of her home, all candles and wood and stone, her fluid working hours, weekly massages, Kelly bags. But you remind yourself that she isn’t happy and probably never will be and it’s a comfort, that. For no matter how much Theo achieves and acquires and out-dazzles everyone else, she never seems content. She’s taught you that people who shine more lavishly than everyone else seem to be penalised by discontent, as if they’re being punished for craving a brighter life. I’ve been knocked down so many times I can’t remember the number plates, she said once.

Many people are afraid of Theo but you’ve never been, perhaps that’s why you’re so close. All the noise of her personality is a mask and when it slips off, on the rare occasion, the vulnerability riddled through her is always a shock.

Lesson 13

it cannot be rational enjoyment to go where you would not like to have your truest and best friend go with you

Hold my hand, Cole says as he steers you through the twilight crush of Marrakech. Neither of you knows the pedestrian etiquette of this city; the cars are coming in all directions, the dusky streets teem like rush hour in New York but everything’s faster, cheekier, more reckless; exhilarating, you think. Mopeds and tourist coaches and donkeys and carts stop and start and weave and cut each other off without, it seems, any rules and the scrum of people funnels you into the great sprawling square at the city’s heart, Djemma El Fna, and you lift your head to the low ochre-coloured buildings around you and break from Cole’s grasp and swirl, gulping the sights, for you feel as if all of life’s in this place. There are snake-charmers with arms draped by writhing snake necklaces, wizened storytellers ringed by attentive men, water sellers with belts of brass cups like ropes of ammunition, veiled women offering fortunes, jewellery, hennaed hands. It’s a movie set of the glorious, the bizarre, the deeply kitsch.

Diz would love all this, you laugh.

Thank God you didn’t bring her.

You’d almost invited her on the spot when she said she was so low. You wanted her to join you just for a couple of days, as a treat: it’s her birthday in three days, June the first. But you knew you’d have to check with Cole first and he wouldn’t stand for it, of course.

She’s weird, he says of her.

You say that about all my friends.

She’s weirder than the rest.

You can’t argue with that. Theo takes the train to Paris just for a haircut. Has a tattoo of a gardenia below her pubic line. Can’t poach an egg. Never watches television. Gets her favourite flowers delivered to herself every Monday and Friday: iceberg roses, November lilies, exquisite gardenia knots. Is married to a man called Tomas, twenty-four years her senior, whom she’s rarely made love to. She has a condition.

What, you’d asked, when she first told you.

Vaginismus. It sounds vile, doesn’t it? Like something you’d pick up in Amsterdam. It means that when anyone tries to fuck me the muscles around my vagina go into spasms. It’s excruciatingly painful.

Theo, darling Theo, of all people. You wrapped her in a hug, your face crumpled, you began to cry.

Hey, it’s OK, she laughed, it’s OK. It’s actually been rather fun.

And she leant back and smiled her trademark grin, one side up, one side down. Took out her little silver case. Lit a cigarette. Said that she’d decided to investigate the whole situation, a woman’s pleasure, and it was so deliriously consuming that it eventually slipped into being a job. Said that most women never climaxed from vaginal penetration: all the fun was in the clit. You’d blushed back then, at hearing the bluntness of that word, there were some things you couldn’t help.

I can’t tell you how many clients get absolutely no pleasure whatsoever out of bog-standard penetration, she said, punctuating her words with savage little taps that made the cutlery jump. We just don’t know how to please ourselves enough. We’ll never learn. We’re still too intent on the man’s pleasure at the expense of our own.

You weren’t entirely comfortable with this talk, it was a little close to the bone. You wanted to know more of her condition, for it was a strange relief to hear that your arrestingly sensual friend also had stumbling blocks over sex: so, Theo was human, too.

Did you get some help, for the vagi, vagis—

Mm, I did. It involved a horrible thing called a dilator.

Did it work?

Well, yes, but when I finally had the sex I’d been waiting for it was such a let-down. It’s so dull compared with everything else. Why didn’t anyone tell me this?

Theo’s wonderful laugh curdled from deep in her belly but there was no joy in her eyes. Her marriage to Tomas was so odd, you couldn’t figure it out. He had other relationships with men as well as women and she had relationships with women as well as men, that was their life. And yet they stayed together. I don’t have any passion in my life, for anything. Not for her husband, whom she says she’s too clever to love. Nor for London, the city of fractious energy you both fled to as teenagers from the same boarding school, almost twenty years ago. Nor for her job, for she says she’s been doing it so long that the stories are now all the same, there aren’t many new plots in people’s lives and she’s found, lately, she’s switching off.

You suspect you attract extreme people like her because you’re so stable, as is Cole. She described the two of you once as eerily content and for some this means unforgivably beige but for others you’re an anchor, always there if needed, even on Sunday evenings, and birthdays, and Christmas Day.

Theo and you have shared your lives since the age of thirteen; swapping Arabian stud magazines for the pictures of the horses, camping overnight for tickets to Duran Duran, devouring books in tandem, from Little House on the Prairie to The Thorn Birds and Story of 0. Having your first cigarette together and the last shower you’ve ever shared with a girl. Standing to the left of each other at wedding altars, knowing you’ll be godmothers to each other’s children.

You met in the same class at a minor boarding school in Hampshire, a place where mediocrity was encouraged. You were not meant to be clever, since being clever did not make you a good wife. If you excelled at anything it was seen as a mild perversion but Theo was stunningly oblivious to that. Not many people liked her at first. She came to the class in the middle of term. She’d developed earlier than the other girls and had foreign parents, New Zealanders, who’d made their money only recently, and not nearly enough. But through force of personality she turned her fortune round and was made a prefect, as were you.

Don’t get too excited, she told you, practically everyone’s been made one. They’ve only done it because they forgot to educate us—it’s something to put on our CVs.

She was expelled for writing to the Pope, explaining to him why the rhythm method of contraception, for a lot of girls, just didn’t work. (She’d learnt this lesson from her older sister, who’d had an abortion in secret.) Her mistake was to sign the letter with the name of a blond classmate who was going to be a model when she grew up and was promised a car, by her father, if she stopped biting her nails. And was extremely accomplished at looking down on you both. The scandal made Theo a heroine-in-exile but she always remained supremely faithful to you, the lady-in-waiting who’d fallen in love with her first.

Here, in Marrakech, you just wish your friend were as happy as you for you want others to be joyous, to bring them joy, you get such a deep satisfaction from that. You’d love to have Theo here, to cheer her up; it’d be someone to see the sights with while Cole was off by himself. You’re always doing small kindnesses; your grandmother told you never to suppress a kind thought and you always try not to. You snap a shot of a snake man in the square and he rushes towards you, hustling for coins and waving his snakes and you squeal away from him, pulling Cole with you. You must tell her.

Lesson 14

be respectable girls, all of you

Dinner’s dared in the square on rough wooden benches at a smoky stall. Cole and you pick at the couscous but ignore the gnarled-looking meat on kebabs and gritty salad, and have your photo taken as proof of your courage. Cole’s tetchy and irritable and wants to get back to the too-quiet hotel but you feel like you’re at the centre of a vast meeting place of African tribes from the south and Arabs from the north and Berber villagers from the mountains and you hold your head high and drink in the smells and heat and smoke. All these wondrous people! You look across at your husband and stroke his arm, his thin, sensual wrist, and there’s a stirring of desire: you want him, really want him, in that way, in this crowded place. You do nothing but hold your lips to his skin in the clearing behind his ear and breathe in. It’s usually enough, some small gesture like this, just to touch him, to inhale him, to remind you of what you’ve got.

But here, now, something dormant within you is stretching awake, is arching its back. You think of the hotel room and the expanse of the bed. For just a fleeting moment you imagine yourself naked with your legs wide and several anonymous, assessing men and their hands running over you. You imagine being filmed, being bought.

You smile at Cole.

What are you thinking, he asks.

Nothing, you murmur.

Lesson 15

there are few wives who do not heartily desire a child

As you laze on your deckchairs a heavily pregnant woman strides to the swimming pool like a galleon in full sail, robust and proud and complete. You’ll be trying for a baby soon, once the first year of marriage is done.

Let’s just enjoy ourselves for a while, Cole has said.

But thank goodness a pregnancy is secure in the plans. Man, house, child: such happiness is obscene in one person, isn’t it? There’s such an audacity in the joy you now feel. How could anyone bear you? You glance across at Cole: he looked too young for so long, not fully formed, but now, in his late thirties, when a lot of his peers are losing hair and gaining weight, it’s all starting to work. He’d been in a state of arrested adolescence but now he’s filled out and he’s handsome, at last. He has the potential to age into magnificence and you’re only just seeing it.

Shouldn’t it be wearing off, this fullness in your heart fit to burst? When’s it meant to wilt? You throw down your Vogue and place your body on Cole’s, belly to belly, and breathe in his skin like a mother does with a child. Will that scent ever sour for you? You can’t imagine how. He pushes you off, mock grumpy, and slaps you on the bum. You shriek and settle again on your lounger. A young waiter walks by. You narrow your eyes like a cat and laze your arms over your head and tell Cole that if you’re not treated properly it’s the waiter you’ll be marrying next.

Yeah, and all he’ll have to do to get rid of you is say I divorce thee three times. I wish it were that easy for me.

You laugh; you’re filled up with joy, it’s all bubbling out. The pregnant woman steps out of the pool. People have begun asking when Cole and you are going to start a family and your husband always replies that he’ll have a child when he considers himself grown-up, and God knows when that will be. You tell them soon.

All women must want children eventually, you’re sure, that furious need is deep in their bones, you don’t quite believe any woman who says she doesn’t. The urge has begun to harangue you as your thirties march on, it’s an animal instinct grown bold. Your heart will now tighten whenever you see the imprint of a friend in her child’s face. It’s something that’s in danger of overtaking your life, the want.

Lesson 16

all nature is lovely and worthy of our reverent study

On a day trip to the Atlas Mountains you hold your head out the car window, to the sky, the scent of eucalyptus on the baked breeze. Cole reads the Herald Tribune and dozes and snaps awake.

He works extremely hard as a picture restorer, specialising in paintings from the fifteenth to the nineteenth centuries. He now travels the globe, preparing condition reports for paintings to be sold and working on site, for since September eleventh the insurance premiums have skyrocketed and it’s often cheaper to fly the restorer to the job. Cole’s days are long but the rewards are great—you no longer have to work. Indolence is something you’ve always wanted to try and this is your second month of doing nothing. Cole encouraged you to quit your job as a lecturer in journalism at City University; he’d bulldozed your trepidation with his enthusiasm. Redundancies were on offer and the sum cleared the mortgage for you both. None of your colleagues wanted you to go; you were a stabilising presence in a temperamental faculty, you kept your head down, worked hard. But you’d been worn thin by years of teaching, the relentless routine of work eat sleep and little else, it had become like a net dragging you down. Theo said you’d been so noble, so selfless as a teacher that it was bound to take its toll. You didn’t tell her it felt cowardly that you’d never actually left university and entered the real world; you just teased that she was a teacher also and every bit as noble as yourself.

God no, I do my job purely for me and no one else. It’s utterly selfish what I get from it.

And what, my dear, is that?

This secret thrill, she grinned, as my clients tell me all their deepest, darkest thoughts.

Your job had stopped being gratifying in any way and you delight in the strange feeling of satisfaction from doing this new wifely life well. You weren’t expecting your days to be swallowed by so many mundanities but you’re oddly enjoying, for the moment, cooking fiddly Sunday meals on week nights and painting the kitchen and sorting through clothes. The days gallop by even though you know that boredom and a loss of esteem could one day yap at your heels. But not now, not yet.

You have little left in the way of savings but Cole pays you an allowance of eight hundred pounds a month. It’s meant a subtle change: he now has a licence to expect darned socks and home-made puddings, to comment a touch too often on your rounded stomach or occasional spots. But his small cruelties are a small price to pay for the luxury of resting. He’s giving you something you’ve never had before: a chance to recuperate and to work out what you want to do with the rest of your life. You’ve been so tight and controlled for so long, always on time and everything just so. During the first month of unemployment you gulped sleep and suspect it’s years of exhaustion catching up on you, all the trying to please, the never being able to say no. Anyway, Cole’s teasing is done in a silly, childlike way and you never mind very much.

On this day trip to the Atlas Mountains he’s here under protest, he wants to go back. He hates activity and the outdoors of any sort, he pretends to be so fusty and curmudgeonly, at such a young age, but you find it adorable, he makes you laugh so much. And there’s an intriguing flip side to his crustiness, the little boy who watches Star Trek and buys Coco Pops. You love the kid in the T-shirt under the Italian suits; you’re the only one, you suspect, who knows anything of it.

On the narrow dirt road the car winds and slows and you want to jump out and whip off your shoes and feel the ochre as soft as talcum powder claiming your feet. You know deep in your bones this type of land, for you visited places not dissimilar, with your mother, when you were young. The Sahara is just over the mountains, the desert of smoking sand and tall skies.

It’s a desert the colour of wheat, says Muli, the driver and guide.

How lovely, and you clap your heavily hennaed hands. The sight of them entrances you. You must take us, Muli, you say.

Cole glances across.

Next time.

You smile and lick your husband under the ear, like a puppy, he’s so funny, it’s all a game, and you’re filled like a glass with love for him, to the brim.