Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

Kitabı oku: «Wrecker»

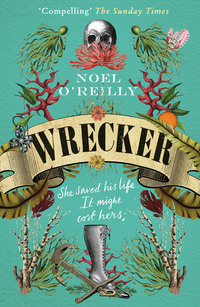

NOEL O’REILLY was a student on the New Writing South Advanced writing course. He has worked as a journalist and editor at the international business media company RBI, and is now a freelance writer. This is his first novel. He lives in Brighton with his wife and children.

Copyright

An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers Ltd.

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by HQ in 2018

Copyright © Noel O’Reilly 2018

Noel O’Reilly asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Ebook Edition © July 2018 ISBN: 9780008274535

‘God moves in a mysterious way

His wonders to perform;

He plants his footsteps in the sea,

And rides upon the storm.’

William Cowper, Hymn (1773)

‘Myreugh orth an vorvoren, hanter pysk ha hanter den.

Y vos Dew ha den, yn-lan dhe’n keth uta-na crygyans ren.’

‘Look at the mermaid, half fish and half human. That

He is God and man, to that same fact let us entirely give credence.’

Louis T. Stanley, Journey Through Cornwall (1958)

To Sally

PENWITH, CORNWALL

TEN YEARS AFTER THE FRENCH WARS OR THEREABOUTS

Contents

Cover

About the Author

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Contents

I: BUDDING TIME

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

II: WHITSUNTIDE

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

III: HARVEST TIDE

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Acknowledgements

About the Publisher

I

BUDDING TIME

1

I got to the beach too late to find anything of real worth. The gale had moved inland, leaving an icy breeze in its wake, and there was a sea stench as if the ocean bed and all its secrets had been torn out overnight and dumped on the strand. All about me the dead from shipwrecks past muttered and moaned in the tongues of their own lands. Having shaken themselves free of their unblessed graves, they shuffled about in search of some lost thing. Look upon them too long, and they’d fade into the mist that sailed across the strand.

A dead wreck it was, all hands drowned. Sounds of hacking and wrenching floated over to me on the gusts, as my neighbours took the ship apart, plank by plank. All that was left was the bare ribs of the hull, stuck between Jack and Jill, two rocks that stood like monsters’ teeth at the western end of the cove. The ship’s bottom was torn out and her timbers lay in piles. Alongside, casks and boxes waited, and ponies and carts laden with plunder filed from the ship up the steep track to the headland. It wasn’t the first time I’d seen a ship picked clean in a single tide.

I rubbed the grit of sleep from my eyes and tied back my hair, casting my gaze all about me to make sure I was alone. On the sand a few passengers lay among the dead, but my neighbours had already stripped the corpses for the most part. Among the bodies lay cabin furniture and fittings, lengths of pipe, a binnacle and other nautical instruments of some use unknown to me. Jellyfish lay all over, like plates of glass with the grey sky trembling inside them. Queerest of all were the hundreds of oranges scattered among the corpses as if they’d rained down from the heavens. They were all the more vivid in a world grey and tired as an old garment with the colour washed out. I took my kerchief from my shoulders and scooped as many as I could carry into it.

A few yards away I saw a human hand lying palm down on the sand. Thinking it might crawl towards me and grab my ankle, I hurried off. Nearby was a severed foot still in its shoe and such other gobbets of human flesh as could hardly be named. Dogs’ barks pierced the air off to the east where hounds were mauling a corpse. My best hope was to move out towards the ebbing tide, where I might find a body freshly washed ashore. As luck would have it, down where the sand was still wet and glistening I found a fine-looking man stretched out. I wove a path towards him, willing myself to touch every corpse I passed for luck. The gentleman wore a dark suit, so sombre he must have had an inkling he was on the way to his funeral when he dressed himself. A well-built fellow he was. If you stood him up he’d be head and shoulders above any man in the village, apart from the giant, Pentecost. I wondered how long he’d struggled in the cold water.

It grew lighter by the minute. Pale lichen showed on the rocks, pink crystal glinted in the seams of the cliffs and the rising sun lit the dead man’s face. His dark hair lay across his cheek, covered in a slick pale rime. There was a gash down one cheek and a shadow of stubble on his chin. There was no smell off him yet, fresh out of the sea as he was. I crossed myself to show contrition before digging into his sodden trouser pockets, searching his wrists and inside his jacket, but I found only a pocket book, the pages stuck together, which I threw aside, and a watch on a silver chain which was full of sea water. Time had stopped and God had turned his back on the world.

When I was done with the man, I rose to my feet and moved through the mist, almost stepping upon a child’s body that lay like a sixpenny doll on the sand. The little thing’s face was turned away, which was a mercy. I went further down towards where the tide was washing out, but was stopped in my tracks by the sight of two pretty boots poking out from under the hem of a woman’s skirt. Though the boots were soaked, I saw they were of the softest tan leather, laced before, with the tops reaching only just above the ankle. It was a fashion new to me. On one toe hung a little rose cut out of leather, but its twin was missing on the other boot. The woman’s feet were daintier than mine, but I would gladly have put up with a bit of pinching around the toes for the chance to be seen in a pair of boots such as those.

I got down on my knees and set about working the boots off the lady’s feet. The first came away easy enough but the other was the devil’s own work. I tugged at the laces, but they were tightly knotted and wet, and in any case my blood was turning to ice and my fingers, usually so strong, were losing their grip. Almost crying with vexation, I pulled with all my might, but the dead woman’s ankle was swollen with water and the boot wouldn’t shift. If only I’d come out with a knife. By now my fingers were so numb I could barely move them, but I gave that boot one last tug and off it flew, so sudden that I hit myself in the mouth with it, and fell backwards onto my ass. For a moment I sat there, winded, my mouth stinging from the blow.

When I got my breath back I put the boots in my kerchief and knotted it. Wasting no time, I got to work searching the rest of the woman’s body. Her frock had been stripped from her and her shift clung to her limbs, cambric silk by the feel of it but rent beyond repair. There was nothing else on her of any value.

A tooth was dangling from the lady’s bottom lip on a pink thread of flesh, so I pulled it out, a charm I might use to cure my Mamm’s windpipe of the chronic. Although it shamed me to look for long at the faces of the dead, I couldn’t help but gaze at this woman. Her dainty upturned nose, black as if charred, stood out against her face that was all the paler for being encrusted with salt. Her eyes were black seams with just the whites showing between them. White sand covered her hair like a hoar frost, and there was a streak of gleaming red on a lock that fell over her ear. Looking closer, I gasped with horror to find her ear lobe had been chewed off. It was the same on the other side, the jagged edges still wet with fresh blood. For a long moment, I shut my eyes, breathing deeply to keep down the hot bile rising in my throat.

As I put the tooth in my apron pocket, I heard a noise, a low moan, more beast than human. Did the woman yet breathe? Had I jolted her back to life by drawing the tooth out of her jaw? Her eyes and mouth seemed to move, but they might have only trembled in the wind. Bubbles rose between her lips, and then – that sound again, part moan and part belch, her bosom rising and falling, and at the last only the hiss of air between her lips. Her soul was fleeing her body, and the thought gave me such a fright I screamed, which set the gulls shrieking overhead letting the whole world know what I was about. I would have fled, but right then I heard footsteps, and a crone in black widow’s weeds loomed out of the fog, planting her crook in the sand at each step, her back-basket a hump on her shoulder and her shawl fluttering behind her. It was Marget Maddern, known to all in the cove as Aunt Madgie. She was the very last person I wanted to see at that moment. The old woman drew up by me and leant on her crook, panting as she looked me up and down, her creased brow crowned by a white mob cap.

‘Was that you screaming just now, Mary Blight?’

I nodded. ‘I had a fearful shock – seeing what some devil have done to this poor lady’s ears.’

Aunt Madgie leant over the woman and looked her up and down, before fixing her gaze on the ragged frills of crimson where the earlobes had been chewed off. She turned and peered at me through narrowed eyes. ‘I hadn’t thought you so faint-hearted,’ she said. ‘I see that for all your tender feelings, you were still able to fill your kerchief.’ She leant closer towards me, looking into my face. ‘What happened to your mouth?’

‘My mouth?’

‘It’s bleeding.’

I put a hand to my lips and saw blood on my fingertips. ‘I bumped into something in the mist and cut my mouth, that’s all,’ I said.

She gazed at the woman’s ears again. ‘Do you swear this is not your doing, Mary Blight?’

‘I do.’ She gave me such a damning stare, I had to look away. I could outstare anyone but her.

‘And yet I found you crouched over the body, and with blood on your lips?’

‘Oh wisht! I confess that I did take the woman’s boots off, and in so doing hit my face with them. I didn’t tell you at first, for I was all of a tremble when I saw you. But it’s the truth, as God’s my witness. Some other devil got here before me and did the rest.’

She gave me a still keener look. ‘And she was dead when you came upon her?’

‘I swear to God.’

‘Take care with these oaths, lest they prove false. Perhaps you thought that while there was still life in the woman, you had no natural rights to take those boots. Maybe you helped her soul on its way?’

‘Never! I am no murderer.’

‘I’d be more inclined to take your word for it, were you less renowned for stripping clothes and jewels off dead women.’

‘I’m not alone in that.’

‘Aye, ’tis true, but we must not cross the bounds of decency, or the cove will be infested with Preventive Men.’ A crow swooped low over our heads and croaked to harry us away from the corpse. ‘It doesn’t belong to you to go sneaking about like this after the hard work is done, Mary Blight. I know your ways, looking for pickings from the last few bodies that drift ashore. And all for vanity. When will you learn that it’s One and All in this cove and always has been? What else have you found this morning? Sovereigns? Spanish dollars? Let me see.’

‘Only some oranges.’ I swayed the heavy kerchief in front of her. ‘And I found this on a man a little way off. A watch that be full of water.’ Fumbling in my apron pocket, I brought the watch out and handed it to her.

‘Maybe we can get it fixed in Penzance,’ she said. ‘Whoever owned this won’t need to tell the time where they’re gone.’

At last, she slowly turned and hobbled away. But before she was gone more than a few yards, she stopped and spoke, her back still turned to me. ‘I’ll have my eye on you, Mary Blight. Take heed.’

With Aunt Madgie gone, I got up and threw my kerchief over my shoulder. The mist had cleared to show a mass of broken clouds flung across the heavens from the east to the west, glowing with the sun’s red fire. But the pale round moon still tarried in the sky, knowing the work of the night was not yet over.

A wreck is a queer purging, when compass reckonings go awry and Nature shakes the world out of order and time out of joint. My first harvest had been in my fifth or sixth year and since then perhaps a hundred ships had broken their backs upon the western rocks. Every time I was left with an unease for days to come. That morning after Aunt Madgie had come upon me on the beach, I could find no peace. My nerves were frayed as it was, having seen the drowned woman’s soul bubble up out of her throat. And then to find myself called to account by the old lady and made to suffer her dark looks! I couldn’t rid my mind of the fear she might accuse me of stealing the noblewoman’s earrings. To put my mind at rest, I went down to the harbour to find out how things stood.

On the slipway a fine chestnut horse with mud-spattered saddle bags was tethered to a post outside a warehouse. Its flanks foamed with sweat and its head hung low as if it had been ridden hard. The beast snorted and scraped a hoof on the stone slabs as I passed. All that was left of the wreckage was a broken old cabinet propped against a barn wall, and a couple of hogsheads with staved-in sides and spoilt cargo. No doubt, the rest was hidden away, safe from the eyes of the Preventive Man, on farms on the moor or down in tunnels, or sunk out at sea waiting to be recovered.

A huddle of men was gathered by the wall of the quayside. I was about to pass when they moved aside to let two fellows through. They were carrying something heavy in a sack, one at each end, and I knew by the way the load sagged between them that it was a body. The sight of it fixed me to the spot. Not one of the men in the group gave me more than a glance, which calmed my nerves a little. The two men bearing the carcass took it to a low black shed on the slipway, where the bodies were kept before they were taken up to the graveyard.

A tall fellow stood in the midst of the men, a foreigner in a long brown cloth coat. It must have been his horse I’d seen. I knew his face from other wrecks. He was an outlier in Penzance for the wrecked ship’s insurer, a loss adjuster. His trousers were streaked with mud, and his shoes covered in sand. A group of men from the village answered his questions while he looked down his nose at them and noted things in a black pocket book. The men shuffled further along the harbour wall and I moved along with them, keeping out of the way. For the briefest moment before the men hid them from view, I saw two bodies laid out on the cold, rough stone, a woman in a tattered and grubby shift and a child of perhaps four or five years old. I crossed my arms and held myself tight to stop myself from shaking.

The loss adjuster looked around at the men in his lofty way, an eyebrow raised, and spoke. ‘So, you’d have me believe that not a single one of you was anywhere near the wreck last night?’ he said. ‘That a five-hundred-ton vessel like The Constant Service could be plundered of every last scrap of its cargo and its timbers broken up while all of you slept, unknowing, in your beds.’ The men shook their heads and tugged at their beards. None would meet his eye. ‘My client Lord S— owned the greater portion of the cargo, but this loss will be as nothing compared to this outrage,’ he said, looking down at where the bodies lay, and scratching out some more notes in his black book. ‘Mark my words, this is not the end of the matter.’ I wanted to slope away, but feared it would seem like I had something to hide.

‘It is the very woman I’m looking for, without a doubt,’ the loss adjuster said. ‘Her face is well known in Society, that is to say the civilised world far beyond this shore. This is a foul crime, and His Lordship will not sleep easy until justice is seen to be done.’ His head jerked to let the men know they should remove the body. Two big fellows stooped to lift the woman up and lay her on a sheet of sacking. It was then I saw her face, and the frills of dried, blackened blood where her earlobes had been chewed off, her jewels pilfered. The child lying alongside her was surely her own. It was lucky I stood by a barn and could lean against the wall, for my legs were going from under me. But the men took no notice, just moved along the wall to look at another victim of the wreck.

My mind raced, thinking of the loss adjuster’s words about a great lord wanting justice, and seeing in my mind’s eye the pretty boots I’d left drying on the hearth in our cottage. I looked away as the two men passed me with their burden slung between them. All that was left of the woman was a wet patch on the stone where she’d lain.

I fled that place and turned up the lane towards home, but after a few paces I felt a feeling like a shadow passing over me, so I stopped and looked about. I found myself at the end of Back Street, the very place Aunt Madgie lived. And there she was, the old devil, as I knew in my bones she would be, standing between the two posts that stood before her ancient house, clad in her black dress as always, one gnarled hand clutching her crook and the other holding an ancient china chamber pot. When our eyes met, she shook her head slowly, before emptying the pot in the lane, making sure to throw it towards where I was standing. As she turned back to the house, she gave me an evil look before doddering inside.

2

The following evening a feast was held to give thanks to Providence. I’d been stricken with sudden qualms all through the day and was sure Aunt Madgie was ill-wishing me, but still I meant to go to the feast. I wanted to see if there was any hint that the old dame had been about among my neighbours spreading lies concerning what she’d seen. If so, it was better to know and be able to fend off the slander.

I got ready for the feast in Mamm’s old room that she hadn’t used since she went wrong in her lungs, preferring to sleep in her armchair by the fire. My younger sister, Tegen, was sat in the straight-backed chair in a royal sulk, watching me. I brushed my red hair, turning this way and that to see myself in the oval looking glass that hung over the rickety linen chest. The glass was cracked and covered in blotches that no amount of rubbing could remove. The mirror was engraved and had once been fine. In my mind’s eye I pictured it standing in a rich woman’s chamber, but when I’d found it on the strand there was a crack running from one side to the other. Now I looked at myself in the glass, cut in two where the surface was split.

A frock and petticoat were hung on rusty nails against the damp wall to let the creases fall out. The garments looked gaudy against the faded lime wash. I dropped a white shift over my head, before putting on a petticoat and a scarlet dress. Of a sudden I remembered the scarlet chemisette I kept in the closet to stop it fading. It was of the same vividness as the dress, and only a little frayed and moth-eaten. The cloth was chill against my skin, and I shuddered, remembering how I’d come by it.

‘Well now, don’t you look a picture in all your finery,’ said Tegen, with a sour pout.

‘I’ll send one of the children up with meat and drink for you and Mamm later,’ I said, pinning a white winter lily in my hair, which I was wearing loose. The bloom gave off such a perfume it made a body near swoon. ‘You’re better off at home, Teg. You’ll only get teased.’

‘I don’t mind a bit of teasing,’ she said, which I knew wasn’t true. ‘But I’d as soon stay at home. The revels is all wrong in my eyes, celebrating when so many poor souls perished. A young child among them.’

‘Well now, someone’s pissed upon a nettle!’ I said, as I went downstairs. Tegen followed me and watched, arms folded, as I went to the hearth to fetch my new boots. They were almost dry and the leather only slightly stained with salt water. I sat down to lace them, then stood up to see how they looked on my feet.

‘It’ll be like dancing on that poor woman’s grave,’ said Tegen.

I pretended to take no notice, and rushed out the door. It was almost dark. My boot heels clacked on the wooden doors of the fish cellars in our little courtyard, which stank on account of Aunty Merryn’s leaky old cat. I slipped through the narrow alleyway, and headed down the steep lane to the harbour. The further I went, the more those boots pinched my toes.

The quay was lit by a row of lanterns that smoked from the fish oil that burnt inside them. Even the savoury pig on the spit had a fishy smell, having been fattened on fish offal. Every bit of the pig would get eaten, all but the squeal. Planks had been laid out across barrels to make a long table. My neighbours had become dear old friends for once, and it was one of those rare times when men and women come together as though it were the most natural thing in the world. The bettermost from the finer cottages on Fore Street sat preening themselves in a little row at the far end of the table. I saw, with a fearful start, that Aunt Madgie was among them. But none gave me a reproving look, so I took my place at the other end between Cissie Olds and the Widow Chegwidden. The first sip of rum burnt my gullet, but soon my blood slowed and a soothing feeling came over me. Cissie piled my plate with fried swine offal chopped up with onion. But I had no stomach for meat, and the sight of stargazy pie made me queasy, with the pilchards poking their noses through the pastry. It seemed that no word of my misdeeds had reached Cissie Olds or the others who sat around me. I downed one rum and then another and before long lost all count. The world swam about me, and I grew reckless.

The children had grown boisterous and little lads kept sneaking over to the table for a nip of rum when their parents’ backs were turned. It was time for their big sisters and brothers to take them to bed. Soon after there was banging at the far end of the table and a hush came over the company. Aunt Madgie stood up to raise the toast ‘One and all’ and everyone but me roared in hearty accord. ‘Now, neighbours, if you’ll excuse me, I shall take to my bed,’ she said, and they all cheered. The old dame knew the dancing would start soon and didn’t want to witness any improper goings-on. Once she’d gone, a weight lifted from me.

Ephraim Lavin, the blind fiddler, was called on to scrape out a few jigs and hornpipes. His son, the little scarper, sat alongside him, thumping out a rhythm on a tub. The dancing began soberly enough. The men took their places in the left file and the women in the right and the shouter numbered us into couples. I had to start with Lean Jack Bodilley, but I took it in good part. When the tune was counted in, Jack took my hand and raised it and we got through the steps without tripping one another up. At each verse we changed partners, and soon my turn with Johnenry Roscorla came about. I remembered the days when Johnenry and me had walked out together and I had a sudden, fierce longing to have him back. I knew he felt the same about me because when we came face to face he was rooted to the spot, gazing into my eyes. He swayed before me and the harbour swayed along with him. He was the most handsome man on earth in the fairy light of the lanterns. I gave him a look to make his knees buckle. Then the other dancers bashed into us and we reeled in a circle with the rest, elbows locking and the men sending their partners spinning into the next man. We women held up our skirts so as not to trip on them as we stamped up and down the line, while the older folk and the lame clapped their hands to urge us on from the benches. It hardly seemed to matter what would happen tomorrow with the smears of light wheeling round my head and Johnenry’s face forever looming up at me and growing more handsome as the night wore on. The men grew rough and hurled us about, some taking liberties, grabbing our waists or clutching at our behinds.

Time passed too quickly. The music petered out and the left-overs of the feast lay spoiling, fit only for flies. Men lay with their heads on the table, snoring amongst the upturned rum pots. Others were laid out on the quay. My feet were sore and my toes crushed after stomping about in those ill-fitting boots. Johnenry and I fell against a harbour post and I was glad of something to prop me up. But the post soon seemed to leave its moorings and began swaying about too. Loveday Skewes stood against another post further along with a face like a whipped dog. She had a habit of nibbling at her fingernails, and she was doing it that moment. Somewhere in my muzzy head I remembered that Johnenry was courting Loveday, and had been a long while since. I shut my eyes to think clearer, but it made my head spin even more. Down along the quay, one or two scolding wives were trying to drag their husbands home, but most people had already taken to their beds. I saw the lily from my hair lying on the stone slabs of the quay, crushed underfoot. I didn’t want to go to my bed. I didn’t want the night to be over and to wake up the next day with that dark and fretful feeling that haunted me, and a pounding headache to boot.

The bettermost women were gathered on the quay. Millie Hicks piped up in her pious wheedling voice. ‘It’s time for we ladies to bestir ourselves, I seem. It don’t belong to women to be abroad at such an hour.’ I always thought of her as a tall bird, a heron perhaps, with her long, thin neck and pointed beak poking forever into places where it had no business.

Millie linked arms with Grace Skewes, Loveday’s mother and the topmost woman in the village, unless you counted Aunt Madgie. ‘It don’t belong to women to drink strong liquor, neither,’ said Grace. Her little group of followers clucked in agreement, as they picked up their baskets, ready for the off. ‘One cup alone do fairly maze a body,’ said Grace, and I thought her eyes swept over me as she said it. It was all because she was sore about Johnenry preferring me to her Loveday.

Nancy Spargo, a big plain woman from the tinners’ cottages on Uplong Row, wandered over from the table where she’d been larking about with some of her mates. ‘Well, it might belong to the bettermost to take to they beds but I be thirsty as a gull and plan on staying out a while longer,’ she said. She bent forward, her breasts almost spilling out of her bodice, screwed up her face and passed wind like a trumpet major. ‘Begging your pardon, ladies, I been fartin’ like a steer all night,’ she said, in a mock lady-like way. ‘Better out nor in, eh?’ She grinned, showing the gaps between her teeth.

I staggered up the steps to the quay. Seeing how linking arms was all the fashion that night, I went over to Nancy and went arm in arm with her. ‘We work as hard as the men, so why shouldn’t we enjoy ourselves along with they?’ I said, stumbling. I would have fallen if Nancy hadn’t held me up.

‘I be only thinking of what is seemly,’ said Millie Hicks, rubbing her long neck the way she did when she was about to bad-mouth a neighbour. ‘Others may look to their own reputations. Come along, Zenobia.’ She pulled her daughter away with her. The girl was her match in piety.

Loveday came over from where she’d been sulking by a harbour post. She was being mollified by her friend, Betsy Stoddern, who had stuck by Loveday and fought all her battles for her since they were little. ‘Some of we still care what folks think of we,’ Loveday muttered, glancing at me.

I wasn’t going to let this pass. I let go of Nancy and walked towards her. ‘What’s she saying of? Say it to my face if you got something to say, Loveday,’ I said. But someone had taken a grip of my arm and was leading me away. I tried to fight them off, but then I saw it was Johnenry, so I went along with him. He had a cup of brandy in his hand. He pulled me down from the slipway and led me out onto the beach.

‘Look, you’ve given me the hiccups,’ I said, slapping him. He pulled me deeper into the night. ‘Wait! Let me take off these boots. They’re fair killing me.’ Johnenry took the boots out of my hand and slipped his arm around my waist. I wondered if anybody was spying on us from the dark windows in Fore Street.

‘You’re all hot and greasy, let go o’ me,’ I said.

‘I worked up a power of sweat jigging with you, that’s why.’

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.