Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

Kitabı oku: «Spike: An Intimate Memoir»

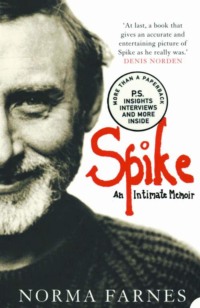

Spike

An intimate memoir

Norma Farnes

For Spike

for changing my life

and

for Jack

for making it better

Table of Contents

Cover Page

Title Page

Foreword by Eric Sykes

Foreword by Spike Milligan

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-one

Chapter Twenty-two

Chapter Twenty-three

Index

P.S.

About the author

Q & A

LIFE at a glance

Top Ten Favourite Raeds

Life Drawing

About the book

A Critical Eye

Read on

If You Loved This, You Might Like …

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Praise

Copyright

About the Publisher

Foreword by Eric Sykes

Many people have written varied descriptions of the life and times of Spike Milligan but nobody is more qualified to give us an accurate version than Norma Farnes, his manager, mentor and troubleshooter for thirty or more years. Spike had three wives who knew the outside view, but Norma knew what went on inside the lad. When the spotlight was on him and the applause prolonged Norma would be in the shadows happy for the lad, but in the many instances of trouble she would be foursquare in front of him deflecting the flak and the bullets, pouring oil over troubled waters until the next time.

Because of the shocking state of my eyesight I am unable to read the book so all I can say is, it feels right. I can assure everyone who reads the book that it is a truthful version of the man himself, although knowing Norma as I do, it has been written with sympathy and a warm heart and heaven help anyone who speaks badly of Spike. Norma is still protective of him and her memory will always remind her of the good times.

But being a Yorkshire girl straight, stubborn and honest this is not a book about the virtues or the vices of Spike but a true version of the man she looked after for years, protecting, encouraging and on occasions gently chastizing. She and Spike made a good team and, sticking my neck out, I believe without the steadying influence of Norma, Spike may well have gone before his time.

September 2003

Foreword by Spike Milligan

I first met Norma Farnes at the same time she was meeting me. I did not know then that it would be a relationship which would last what appears to me to be 300 years, during which I aged prematurely due to the terrible inroads she was making into my private life – like lending me money when I was skint. This was heroic on her behalf because she was skint.

It was due to her that I spent the money very slowly, not exceeding more than £3 on a dinner I gave for the Prince of Wales; and he, suspecting a very small outlay, brought sandwiches. I got him to autograph one for me which I proceeded to eat on the anniversary of the Battle of Trafalgar; for the simple reason one of my ancestors was mortally wounded on the fore deck of H.M.S. Victory and never forgave Nelson and, in fact, on his death bed was heard to say ‘F … Nelson’ but he never did and nobody was to blame.

This foreword is written for my Damager/Saviour’s book – God help me.

In the dark days at the beginning of the 300 years we spent together I told her I wasn’t making any more decisions. She said she’d make them if I stuck by them – she’s been doing it ever since – so everything is her fault, and I’m still working for her.

December 1998

Chapter One

‘What’s he really like?’

Whenever and wherever I was introduced as Spike Milligan’s manager and agent I waited for the inevitable question. In not far short of thirty-six years it never altered. It was not one that could be answered in a few words so I generally made do with ‘Interesting’ or ‘Don’t ask’, the latter reserved for the days when either Spike or I had slammed the phone down on the other, or in his case perhaps flung it through the window. Then came the second question.

‘How on earth do you put up with him?’

Sometimes I wondered myself, though not for very long. My answer was invariably ‘He’s very stimulating.’ The truth went much deeper. He could be lovable, hateful, endearing, despicable, loyal, traitorous, challenging, sometimes all of these things in a single day, but always original and never boring. I remember days of laughter and tears, exuberance and despair, and not a single one that was monotonous.

While I was with Spike he went through depressions, marriages, numerous affairs, and very many tantrums. And at the same time there were always those flashes of inspiration, occasionally genius, that made him comedy’s most influential innovator in the last fifty years, and a fascinating human being. People either adored or detested him. Nobody ever dismissed him with ‘Oh, he’s okay.’ His disciples – and I use the word advisedly – worship him to this day. To them he could do no wrong, a view not shared by everyone, including me.

When I walked into Nine Orme Court, Bayswater, on a stormy winter’s morning in January 1966 I never imagined I would spend the better part of four decades with the truly extraordinary man who was about to interview me. Perhaps the weather was trying to tell me something.

I had been looking for a job in television production but then I spotted an intriguing advertisement in the Evening Standard:

Showbusiness personality requires personal assistant. Must be bright and efficient. Good shorthand and typing speeds. Bayswater area. Ring Alfred Marks Bureau, Notting Hill Gate.

That would do for the three months I reckoned it would take to get into television, and Bayswater was only a fourpenny fare and two tube stops from my flat in Kensington. I rang up and the salary was attractive too. I did not have any money so that was in the job’s favour. The girl at the agency wanted to know my shorthand and typing speeds, where I had worked previously and whether I had references. I satisfied her on all those counts. Then she seemed to hesitate.

‘Yes?’ I said.

‘Just one thing,’ she said. ‘You’d be working for Spike Milligan.’

In her dreams.

‘No thanks. I’ve heard all about him. Not for me.’

‘He really is a very nice man. Do go and see him.’

Spike was a notoriously turbulent character, but it would pay the bills and provide an introduction to the world I was interested in. And after almost three years as secretary and researcher to a driven newspaper and television journalist, being Spike Milligan’s assistant should not be too daunting. I had had all the temperament bit, curses, tantrums and books being thrown across the office. Surely it could not be much worse than that. Was I in for a surprise.

Even after Spike’s death I still have my office at a strangely quiet Number Nine, where I manage his affairs for his children. His presence lingers and it will for as long as I remain his surrogate. Every time I arrange for a new edition of his books or scripts I recall the circumstances, the rows, the highs and lows that gave birth to them. If I am asked to do something that I know would not be right for him I hear his whisper. ‘That’s right, Norm. You tell ’em!’ Other great talents, household names, worked at Number Nine, but it was Spike’s moods that coloured the days and set the tone.

Strangers often wonder, even suggest with a knowing look, that there must have been something going on between me and Spike for the association to have lasted. But there never was and that is perhaps one of the reasons we stayed together. He was my greatest friend and I was his, though I told him when I thought he was wrong and that did not always go down too well. As well as his manager and agent I was his peacemaker and confidante, and what confidences there were.

Spike had his own explanation for why we stuck together so long.

‘I’ve always fought against being dominated by strong women. You’re one but with you there’s one important difference. You’re in my corner.’

And I always was.

A long stay was the last thing on my mind when I entered the stately Edwardian house for the first time. I walked into a bright reception area with a red carpet which continued on up the stairs and landings. The receptionist was friendly and we chatted until the switchboard buzzed. ‘You can go up now,’ she said, ‘it’s the first door on your left.’

As I walked upstairs I wondered whether Spike Milligan would be as extraordinary as his public persona. He had converted the post-war radio audience to his crazy, anarchic sense of humour with The Goon Show. As a performer he was guaranteed to fill West End theatres: his unrehearsed antics convulsed spectators and unnerved the actors appearing alongside him. By the time I met him he was famous in South Africa, New Zealand, Australia, Canada and the United States, where he had gathered a following among students and – something that baffled him – intellectuals. Yes, it was rumoured that he was unpredictable and eccentric. Well, I had had a dose of that already and decided in advance that my stay with him would be for three months only.

I stepped into a small cold room. French windows were open to a balcony and let in an icy draught. He was apparently oblivious to the temperature, no doubt because he was sitting there in a thick grey ribbed sweater, black corduroy trousers and a black woolly hat topped with a pompom. He looked up but did not greet me.

‘It’s freezing in here,’ I said.

‘Yes,’ he said. ‘I hate the Americans.’

Well, naturally. That explained everything. I later discovered that this reply summed up Spike’s convoluted logic, and its speed was typical of him. He would always fly to the conversational winning-post while others laboured over the hurdles of qualification and explanation, and he expected you to fly with him. If you could not, then bad luck. Should I tell him that the Romans invented central heating and not the Americans? I decided to leave it.

I looked around the office. On top of a filing cabinet to his right were some packets of Swoop bird seed. Reminders of his family crowded every available surface. Drawings by his children; a very old toy dog; a much-cuddled teddy bear; two pairs of baby boots; a wool bonnet; and a large brown rosary which lay beside a smaller green one underneath a picture of a benevolent Jesus Christ. I wondered what His views were about all that went on in that room. Although there was electric light numerous oil lamps were dotted about, two on top of an upright piano before which stood a rickety chair. Shelves packed with files lined three walls and the fourth was covered with photographs of his children. A large Victorian bureau, double doors open wide, revealed numerous compartments, all open and filled. Every file, cassette and tape it contained looked to be neatly labelled. Under another window was a divan bed. What initially seemed chaotic had a streak of unorthodox order about it, not unlike the workings of his mind, as I would find out. Even a glance told me that this room was a refuge to him, and somewhere to kip when he felt like it.

He opened the conversation with a few desultory questions, none of which amounted to much. I waited for him to get down to business. And waited.

The Bureau had said he was forty-nine but at first glance he looked older, with what is now called designer stubble and was then considered the sign of a man too lazy to shave. There was an air of vulnerability about him and, despite my first impression, something childlike in his manner which made him seem younger than his years. We talked about this and that. Then, without any warning, looking me straight in the eye, he said, ‘You won’t mind if I shout at you from time to time, will you?’

I had had experience of that sort of thing before. ‘No. Not if you don’t mind if I shout back.’

He appeared crestfallen. ‘You must never do that. It would break me up.’ I could tell from his expression that it would. Suddenly he got up, took one of the packets of Swoop and sprinkled some seed over the balcony floor and the empty window boxes. ‘Morning, lads,’ he said, looking into the sky. Within a minute or so there were half a dozen pigeons tucking in.

He turned to me, pointing at the birds. ‘That’s Hoppity. He’s a bugger, first every time. I reckon he’s an argumentative sod, always in fights. I bet that’s why he’s lame.’ He sat down behind a table and gazed at me, nothing rude about it, more of a dispassionate survey, I felt. ‘You’ve got legs just like Olive Oyl,’ he said. ‘Who’d want to make love to an elastic band?’

‘Another elastic band.’

He grinned. ‘You’ll do for me.’

I wondered whether he would do for me.

He told me that at the end of February he was going to Australia to see his parents and do some work. When he came back at the end of June he would be in touch. I had not bargained for that but decided to stick with my job at the Independent Television Companies’ Association (ITCA) in the meantime, keeping an eye open for a vacancy in television production. I quite fancied working for Spike so if nothing spectacular came up I would wait for his call.

June came and went and he had not rung. Then the Alfred Marks Bureau called. They wanted my permission to give Spike my telephone number, which he had lost. A few minutes later the phone rang.

‘Spike here. I’m back from Oz. Do you want to come and see if you still want to work in this madhouse?’

I had had long enough to consider whether it was the right move but there would be no harm in seeing him again. So off to Number Nine for the second time. And I met a completely different Spike: bright, alert and brimming with energy. Yes, I thought, I’ll give it a whirl, if only for a few months. It might be fun.

I told him I would have to give a month’s notice to the ITCA so could start at the end of August. That was fine by him because he was taking his family on holiday to Tunisia so would see me again on 29 August. He took me downstairs to a room immediately behind reception and left me with his agent, David Conyers, to sort out the details. David suggested I start early and have a week to settle in before Spike’s return. It was all very informal. Yes, I thought to myself, it could be very pleasant working here.

Chapter Two

I could have been born in a different galaxy from the frenetic world of Number Nine. In fact it was at 45 Barnard Street, Thornaby On Tees, on New Year’s Eve 1934. The town, tucked between Middlesbrough and Stockton, was still suffering from the deprivations of the Depression. My father was lucky with a construction job at ICI Billingham, a dangerous occupation but comparatively well paid. My mother was a rarity in those pre-war years because she was a working mum and served behind the counter of Robinson’s, an upmarket department store.

At that time sons and daughters generally lived in the same neighbourhood as their parents and family ties were strong, if somewhat binding for those with an instinct to break the mould. After school, when my friends had tea with their mums, I went to my maternal grandmother’s house, two doors away from our own. When Mum finished work she often came for tea with us, not a dainty Ritz-like affair with cucumber sandwiches but a knife and fork meal with ham and salad or a Newbould’s pork pie.

My parents were judged to be somewhat unusual. They were among the very few people on our street to cast their votes for the Conservative Party and did not mind who knew it. And although my straight-as-a-die Dad conformed to the archetype of the working man in that he was a sports fanatic, there the resemblance ended. He went to his barber every Saturday morning, not just for a haircut but a manicure. He must have been the only manual worker on Teesside to do so. He was also a non-smoker and almost teetotal, but could be persuaded to have a whisky at Christmas. And he was potty about variety theatre.

As soon as he decided I was old enough Dad took me with him to the Middlesbrough Empire on Wednesday evenings, Saturdays too if there had been a change of act during the week. The ritual never altered. At the interval he would say, ‘Come on. We’ll go and see Ally at work in the Circle Bar.’ In fifteen minutes Ally could serve more pints than it is possible to imagine. Although a big woman she would swoop gracefully from customers to the pumps, arrange six pint glasses in a hand as big as a navvy’s and fill them with just the right amount of froth on top. Then in one fluid movement she would bang the pints down, take the money, scatter change on the counter and somehow pull another six.

Visitors from out of town were told not to miss Ally. Even the artistes came to witness her performance. ‘She’s a class act,’ my father claimed he heard one customer tell a comedian who had died before the interval. ‘Better than owt on stage. So far, that is.’

Dad’s favourite acts were peerless comic Jimmy James; Wilson, Kepel and Betty, the sand dancers; comedians Rob Wilton and Billy Bennett, and the incomparable G. H. Elliott, who, blacked-up, sang ‘Lily of Laguna’ hauntingly as he glided across the stage. Above all Dad idolized a great ballad singer, fiery Dorothy Squires. After meeting in the Empire bar they became friends and he looked out for her, not that she needed any help because she could be as tough as a bar-room brawler. Whenever she was within travelling distance of Thornaby Dad would be in the audience, and through all her tempestuous affairs he was the one who listened quietly to talk of her latest love and the inevitable parting which had given her so much pain – temporarily at least, for there was always a new man in her life. (This was before she married Roger Moore.)

Dad knew that Dorothy could be a demanding monster with the hide of a politician, and, like many of that breed, she was often ruthless and unforgiving. But because of her talent he excused her frailties. She was the very opposite of my mother. Mum never threw tantrums, was content with her lot and, in the jargon of today, she gave Dad space to enjoy his interests. It was not all one-way traffic, though. Mum took the view that what was good for him was good for her so she went to the local dance halls with her girlfriends. Strange as it may seem, I am sure neither of them strayed.

My parents often went backstage to see Dorothy after the curtain came down and one evening, when I was about twelve years old, they took me along with them. I was utterly bewitched by this glamorous singer.

As well as inheriting my parents’ love of entertainment I also picked up their pecuniary habits. In those depressing times half the men in our street were unemployed and dependent on the dole and often the pawnshop. If they could wangle something new for the house it would be on hire purchase. My parents considered this a device of the devil. If they could not pay cash they did without.

Religion played a large part in my mother’s life. She said her prayers every night until she died so it was not surprising that I was sent to Sunday School from an early age. It was never a chore to me and at fourteen I was asked to teach the younger children there. I did it for three years until I fell out with the new vicar.

Everyone in my extended family seemed content with their way of life, as they remain to this day, and yet in my teens I had an urge to get away, to broaden my horizons and to travel. There had to be something more interesting than a future in Thornaby.

Many people reminisce about golden school days but they could not end soon enough for me. I was good at shorthand and typing, becoming sufficiently proficient to teach both for a time at night school, but did not shine at anything else apart from sport. After I left at sixteen my first job was at Head Wrightson, a local steelworks, as receptionist, typist, telephonist and general dogsbody. The manager, a Mr Cussons, treated everyone with charm and courtesy and inspired a family atmosphere. But as with most families, there was an awkward one, the pinstriped junior manager of our small office. Bombastic and opinionated were his better traits. One day some money was found to be missing and he as good as accused me of stealing it. When I went home that evening I told my father. He was furious.

‘Right, I’ll come to the office with you and have it out.’

‘No,’ I insisted. ‘I’ll do it myself.’ I did not want anyone to think I was a wimp.

Dad advised me to confront him and demand that he should call the police. When I did he spluttered like a pricked sausage and I knew I had come across my first bully. He flushed and scuttled out of the office, but did not have the grace to apologize, although the missing money was not mentioned again. In my remaining time there he kept out of my way, which was fine by me. But after eighteen months I got itchy feet and successfully applied for a job as shorthand typist at ICI, then the largest employer on Teesside, at Kiora House, a mansion two miles north of Stockton.

I was there for three years, at first in the typists’ pool under the strict eye of Winnie Gatenby. She was not the Miss Brodie type, more Mother Hen, because her girls were definitely not crème de la crème. Rather we were young, boy crazy, and spent our days discussing the shortcomings or otherwise of the young men who worked in the building and what had happened at the Saturday dance at Saltburn Spa. Winnie often had to crack the whip, which she always did rather apologetically.

It was a very happy office. There was the usual flirting but cupboards were used for their intended purpose and it was all fairly innocent. I have no memories of winters at Kiora. It always seemed to be summer, with sandwich lunches on the lawn, where we would bask and gossip until it was time to return to work. It was then that I developed a crush on a BBC television newsreader, Kenneth Kendall. I cut his photograph out of the Radio Times and stuck it on the wall to the left of my desk so I could gaze at it every time I flicked back the typewriter carriage. My dream was to meet him but as he was out of reach I was left with the local talent. I was quite devoted, however, and when we were moved to another ICI country house, down came Kenneth and up he went on another wall in our new home.

But I felt restless, and soon afterwards I realized a long-held ambition to go to modelling school. I had always been interested in fashion and grooming. ICI gave me a leave of absence and Dad the necessary wherewithal, and off I went to the Lucy Clayton School in Grosvenor Place, London, which was then considered to be the very best. There I joined twenty girls for a month-long course. Although at five feet five I was an inch too small to qualify for the Mannequin Certificate, the all-important diploma for those who wanted to follow in the footsteps of Barbara Goalen and my idol, Fiona Campbell-Walters, I graduated in every other respect.

It was an exciting month. The girls were different from my friends at home. All were extremely clothes-conscious and some very blah, but others brought a mixture of accents from all over the country. This was at a time when anything but an educated southern accent was a problem for the ambitious, so those of us from the Midlands and North Country were encouraged to lose them. I was an eager learner. We were shown how to use cutlery, how to make introductions and, most importantly, how to look after clothes and shoes. Of an evening we met in coffee bars – the new rage to hit London and later to spread to the provinces – and talked excitedly about how the course would change our lives. When we parted, sometimes close to midnight, I travelled safely to South London where I was staying with a cousin.

The experience opened the door to a glamorous new world and gave me poise and confidence. It had never been my intention to make a career of modelling, but when I returned to Thornaby I was offered evening and weekend jobs by Robinson’s and a hairdresser who had made a name for himself on local television. So typing was interspersed with fashion shows but my feet became even itchier than before. Local girls and boys seemed drab in comparison with their metropolitan counterparts. Nonetheless recruiting nights continued with my best friend, Pat Howden, at the dear old Saltburn Spa. We never missed a Saturday night of flirting. And we started planning for our summer holidays.

After a taste of London sophistication I was thirsty to travel further afield than Blackpool, where my parents used to take me every year. Package holidays were then in their infancy and flights expensive. Only the moderately wealthy took a ferry across the Channel and drove down Route Nationale 7 to magical places such as Juan-les-Pins, St Tropez (then still a fishing port), Cannes and Nice. But our imagination was fired by news stories of young people who had hitch-hiked their way to the sun and we were desperate to do the same. The trouble was that our parents were equally desperate to save us from the white slave trade, which they were convinced flourished twenty-two miles the other side of Dover. Throughout the winter of 1953 we pleaded our cause.

France! The home of the Folies Bergére, teeny-weeny bikinis, chic, garlic and Gauloise cigarettes. Mum was fearful, Dad apprehensive, but eventually they gave their permission, with one big proviso: I must not do anything that might bring shame to the family. Not the shame that dare not speak its name – coming back pregnant – but even losing you know what. Mum had heard that girls purposely dressed skimpily to catch the eye of drivers as they raced to the sinful south and she was adamant that my clothes should be modest. The same condition was placed on Pat so we left Thornaby dressed demurely in passion-killing long shorts. As soon as we were out of sight we changed into pairs that were short and tight enough to make sitting down an artful manoeuvre, packing the long ones at the bottom of our rucksacks to be retrieved on our return.

Those cheek-popping shorts served us well and they certainly made drivers take their eyes off the road, so much so that we were able to disdain offers of lifts from lorries and small cars; luxury sedans and saloons became our favoured mode of transport. We were careful to stay on the main road to the south, never hitched after five o’clock and as travelling was free we stayed at decent hotels, not only because they were cleaner but because they might contain eligible young men.

Over the next few years I went back to France and visited Italy and Spain with Pat and then another friend, Aideen Thornton. On the second trip I met someone who made a lasting impression, though we knew each other for only a few days.

It happened on the Champs Elysées. Aideen was taking my photograph with the boulevard’s nameplate in the background so I could show off back home. Then as it was her turn a tall man in his late twenties asked, ‘Would you like me to take both of you?’ Talk about hearts stopping. He was a young English Gary Cooper, slim, smart and outrageously handsome. Unbelievably, he said he was hitch-hiking. Hitch-hiking! He looked as though his everyday conveyance should be a Rolls.

‘Where to?’ I asked.

‘Juan-les-Pins. And you?’

There was no hesitation. ‘Juan-les-Pins.’

He smiled captivatingly. Would we care to join him for coffee? Would we. Over coffee he proved to be a fabulous raconteur. He knew Paris like a native and the afternoon whizzed by. How about dinner at this tiny bistro? How could we refuse? With him I would have shared a baguette on the beach. John, as he was called, told us he was staying in Paris for three or four days and between us we soon persuaded Aideen that we should do the same, to see the sights, of course.

He was the most charming man I had ever met, always immaculate in a spotless white shirt and one of those famous public school ties. He showed us Paris as expertly as, and a lot more charmingly than, a tourist guide but every evening at nine o’clock he turned Cinderella. He would look at his watch, apologize and leave. I wondered who she was.

On the morning we were to say goodbye he arrived with two brown carrier bags. His luggage. I could not believe it. True, he said. Inside the first, very neatly folded, was his underwear, plus three or four white shirts, a toilet bag and a jar of Frank Cooper’s coarse-cut marmalade. In the second was a pair of shoes by John Lobb, complete with trees. They weighed a ton. Definitely an eccentric, I thought. Why did he not carry everything in a rucksack like other hitch-hikers?

If I had asked him to wear brown boots in London he could not have been more horrified. ‘Oh dear me no. Most definitely not.’ There was a suggestion of a shudder. In his world rucksacks were definitely not de rigueur. I was glad he had not seen us on the road.