Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

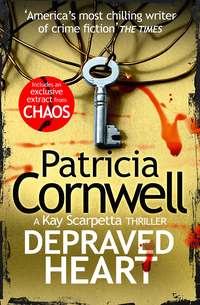

Kitabı oku: «Depraved Heart», sayfa 2

2

“Has anybody asked the Doc?” The voice belongs to Cambridge Police Officer Hyde. “I mean marijuana could do that, right? You smoke a lot of weed and get high and have some bullshit brainstorm like how about I change a lightbulb while I’m naked? That sounds smart. Right? Ha! Real damn smart, right? And you fall off the ladder in the middle of the night when no one’s around and crack your head open.”

Officer Hyde’s first name is Park, a terrible thing to do to a child and he gets called every insulting nickname imaginable and returns the favor. To make matters worse Officer Park Hyde is pudgy and short with freckles and kinky carrot-red hair like a bad parody of Raggedy Andy. He’s not in my line of sight at the moment. But I have excellent hearing, almost bionic like my sense of smell (or that’s the joke).

I imagine odors and sounds as colors in a spectrum or instruments in an orchestra. I’m good at singling them out. Cologne for example. Some cops wear a lot of it and Hyde’s masculine musky fragrance is as loud as his voice. I can hear him in the next room talking about me, asking what I’m doing and if I’m aware that the dead woman was into drugs, was probably a psych case, a whacko, a frequent flying loony tune. The cops are wandering around bantering as if I’m not here, and Hyde leads the charge with his boisterous clunky snipes and asides. He doesn’t hold back, especially when it comes to me.

What’s Doc Mort found? How is Chief Zombie’s leg after you know …? (whisper, whisper) What time is Count Kay returning to her coffin? Shit. I guess that’s not a good thing to say considering what went down two months ago in Florida. I mean do we know for a fact what really happened at the bottom of the sea? We sure it wasn’t a shark that got her. Or maybe she speared herself accidentally? She’s okay now, right? I mean that really had to fuck her up. She can’t hear me, right?

His words and not-so-quiet whispers are around me like shards of glass that glint and cut. Fragments of thoughts. Ignorant banal ones. Hyde is the master of dumb nicknames and comes up with dreadful puns, and I remember what he said as recently as last month when a group of us met at the Cambridge watering hole Paddy’s to toast Pete Marino’s birthday. Hyde insisted on buying me a round, on treating me to a stiff drink, maybe a Bloody Mary or a Sudden Death or a Spontaneous Combustion.

To this day I’m not sure what the latter is but he claims it includes corn whiskey and is served flaming. It might not be lethal but will make you wish it were he must have said five times. He dabbles in comedy, occasionally does stand-up in local clubs. He thinks he’s quite entertaining. He’s not.

“Is Doctor Death still here?”

“I’m in the foyer.” I drop my purple nitrile exam gloves into a red biohazard bag, my Tyvek-covered boots making slippery sounds as I move around the bloody marble floor, staring at the display on my phone.

“Sorry, Doctor Scarpetta. Didn’t know you could hear me.”

“I can.”

“Oh. I guess you heard everything I was just saying.”

“I did.”

“Sorry. How’s your leg?”

“Still attached.”

“Can I get you anything?”

“No thanks.”

“We’re making a Dunkin’ Donuts run.” Hyde’s voice sounds from the dining room, and I’m vaguely aware of him and other cops walking, opening cabinets and drawers.

Marino’s not with them now. I no longer hear him and don’t know where he is inside the house and that’s typical. He does his own thing and he’s competitive. If there’s anything to find he’ll be the one who does, and I should be looking around too. But not now. My priority this moment is the image of four-eleven, what we used to call Lucy’s FBI dorm room in Quantico, Virginia.

So far the recording is devoid of people, narration or even captions as it plays on second by second, offering nothing but the static image of Lucy’s empty stark former quarters. I pay attention to the subtle background sounds, turning up the volume, listening though my wireless earpiece.

A helicopter. A car. Gunshots on distant firing ranges.

Footsteps and I listen carefully. My attention beams back into the real world, the here and now inside this historic house on the border of the Harvard campus.

I detect the hard rubbery tread of the uniformed cops walking toward the foyer. They don’t have plasticized covers over their shoes and boots. They aren’t investigators or crime scene techs, not Officer Hyde, not any of them. More nonessential personnel, and there have been plenty of them in and out since I got here about an hour ago, not long after thirty-seven-year-old Chanel Gilbert was found dead in the mahogany entranceway near the big solid antique front door inside her historic home.

How awful that discovery must have been, and I imagine the housekeeper letting herself in through the kitchen door just like she did every morning, she told the police. Instantly she would have noticed the extreme heat. She would have noticed the stench and followed it to the foyer where the woman she worked for is decomposing on the floor, her face discolored and distorted as if she’s enraged by us.

What Hyde said is almost true. Allegedly Chanel Gilbert fell off a ladder while changing lightbulbs in the entryway chandelier. It sounds like a bad joke but it’s anything but funny to see her once slender body in the early stages of putrefaction, bloated with areas of her skin slipping. She survived her head injuries long enough to have bruising and swelling, her eyes slitted and bulging like a bullfrog’s, her brown hair a sticky bloody mass that reminds me of a rusting Brillo pad. I estimate that after she sustained her injuries, she was lying on the floor unconscious and bleeding as her brain swelled, compressing her upper spinal cord and eventually shutting down her heart and lungs.

The cops aren’t suspicious of her death, not sincerely no matter what they discuss or claim. What they really are is voyeuristic. In their own unseemly way they’re enjoying the drama and it’s one of their favorites. Blame the victim. It must be her fault. She did something to cause her own untimely death, a death that was stupid. I’ve heard that word several times too and I’m not at all happy when people close their minds to other possibilities. I’m not convinced this is an accident. There are too many oddities and inconsistencies. If she died at some point late last night or early this morning as the cops suspect then why is decomposition this advanced? As I attempt to figure out time of death what keeps coming to mind is a Marino turn of phrase.

Cluster fuck. That’s what this is and my intuition is picking up on something else. I sense a presence inside this house. A presence beyond the cops. Beyond the dead woman. Beyond the housekeeper who showed up at quarter of eight this morning and made a shocking discovery that ruined her day to put it tritely. I sense something that unsettles me and I have no empirical explanation for it and don’t intend to say a word.

I usually don’t share my so-called gut feelings, my intuitive flashes, not with cops, not even with Marino. I’m not expected to have any impression that isn’t provable. In fact it’s worse than that if you’re me. I’m not supposed to have feelings and at the same time I’m accused of not having them. In other words a catch-22. In other words I can’t win. But that’s nothing new. I’m used to it.

“Ma’am?” An unfamiliar man’s voice but I don’t look up as I stand in the foyer, covered in white Tyvek from head to toe, my phone in my bare hands, the body of the dead woman several feet away near the upright ladder.

Profession unknown. Kept to herself. Attractive in a sharp off-putting way, brown hair, blue eyes based on the driver’s license photo I’ve been shown. The daughter of a juggernaut Hollywood producer named Amanda Gilbert, the owner of this expensive property and on her way to Boston from Los Angeles. That much I know and it explains plenty. Two Cambridge cops and one Massachusetts state police trooper are now passing through the dining room talking loudly about movies Amanda Gilbert has or hasn’t made.

“I didn’t see it. But I saw the other one with Ethan Hawke.”

“The movie that took twelve years to make? Where you watch the kid grow up …?”

“That was kinda cool.”

“I can’t wait to see American Sniper.”

“What happened to Chris Kyle? Unbelievable right? You come home from the war a hero with a hundred and eighty kills and some loser takes you out on the firing range. Sort of like Spider-Man dying from a spider bite.” It’s Hyde who’s saying this as he and the other two cops hover near the staircase at the edge of the foyer, not coming any closer to me or the stench that holds them back like a wall of foul hot air. “Doctor Scarpetta? Like I was saying? We’re making a coffee run. Anything for you?” Hyde has widely spaced yellowish eyes that remind me of a cat.

“I’m fine.” But I’m not.

I’m not even close to fine despite my demeanor as I hear more gunshots and see the firing ranges in my mind. I hear the dull clank of lead slamming into steel pop-up targets. The bright chink of ejected metal cartridge cases bouncing off concrete shooting pads and benches. I feel the southern sun heavy on my head and the sweat drying beneath my field clothes during an era when everything was the best and worst it’s ever been in my life.

“What about a bottle of water, ma’am? Or maybe a soda?” It’s the trooper talking to me between coughs, and I don’t know him but we won’t get along if he insists on calling me ma’am.

I went to Cornell, to Georgetown Law and Johns Hopkins medical school. I’m a special reservist colonel in the Air Force. I’ve testified before Senate subcommittees and have been a guest at the White House. I’m the chief medical examiner of Massachusetts and director of the crime labs among other things. I didn’t get this far in life to be called ma’am.

“Nothing for me thank you,” I reply politely.

“We should just get a couple gallons of coffee in those cartons. Then there will be plenty and it will stay hot.”

“A hell of a day for hot coffee. How ’bout iced?”

“Good idea since it’s still hot yoga in here. I can’t imagine what it was like earlier.”

“An oven. That’s what.” More dreadful coughing.

“Well I think I’ve sweated a couple quarts.”

“We should be wrapping it up pretty soon. An open-and-shut accident, right Doc? The tox will be interesting. You wait and see. She was stoned and when people are high they think they know what they’re doing but they don’t.”

“High” and “stoned” are two different psychoactive states, and I don’t believe weed is an explanation for what happened here. But I won’t give voice to what’s passing through my thoughts as the trooper and Hyde continue their ping-ponging quips and cranks. Back and forth. Back and forth monotonously, tediously. What I really want is to be left alone. To watch my phone and figure out what the hell is happening to me and who’s responsible and why. Back and forth. The cops won’t shut up.

“Since when are you such an expert, Hyde?”

“I’m just stating the facts of life.”

“Look. With Amanda Gilbert on her way here? We’d better answer everything even if there’s not a question. She probably knows all kinds of important people in high places who can cause us heartburn. For sure the media will be all over this if they don’t already know about it.”

“Wonder if she had life insurance, if Mama took out a policy on her unemployed druggie daughter.”

“Like she needs the money? You got any idea what Amanda Gilbert is worth? According to Google about two hundred million.”

“I don’t like that the air-conditioning was turned off. That’s not normal.”

“Yeah and I make my case. That’s exactly the sort of thing people do when they’re stoners. They pour orange juice on their cereal and carry snowshoes to the tennis courts.”

“What do snowshoes have to do with anything?”

“I’m just saying it’s different from being drunk.”

3

They talk to each other as if I’m not here, and I continue looking at the video playing on my phone. I continue waiting for something to happen.

I’m more than four minutes into it and can’t pause or save it. Every key I touch, every icon and menu is nonfunctional and the recording rolls on but nothing changes. The only movement I’ve detected so far are the subtle shifts of light from the edges of the closed slatted blinds.

It was a sunny day but there must have been clouds or the light would be steady. It’s as if the dorm room is on a dimmer switch, bright then not as bright. Clouds moving across the sun I deduce as Hyde and the trooper hover near the mahogany staircase, loudly voicing opinions, making comments and gossiping as if they think I’m obtuse or as dead as the woman on the floor.

“If she asks I don’t think we tell her.” Hyde has stayed on the subject of Amanda Gilbert’s anticipated arrival in Boston. “The air being turned off is a detail we want to keep away from her and for sure keep out of the media.”

“It’s the only thing weird about this. You know that gives me a bad feeling.”

It’s certainly not the only thing weird about this, I think but don’t verbalize.

“That’s right and it starts a shit storm of rumors and conspiracy theories that end up all over the Internet.”

“Except sometimes perps turn off the air-conditioning, turn on the heat, do whatever to make a place hot so they can speed up decomp. To disguise the correct time of death so they can create an alibi and screw up evidence, isn’t that true, Doc?” The state trooper with his Massachusetts accent addresses me directly, his r’s sounding like w’s when he’s not coughing.

“Heat escalates decomposition,” I reply without looking up. “Cold slows it down,” I add as I realize what it means that the dorm room walls in the video are eggshell white.

When Lucy first started staying at Washington Dorm the walls in her room were beige. Later they were repainted. I recalculate my timeline. The video was taken in 1996. Maybe 1997.

“Dunkin’s got pretty good breakfast sandwiches. Would you like something to eat, ma’am?” The trooper in his blue and gray is talking to me again, sixtyish with a belly and he doesn’t look well, his face wasted with dark circles under his eyes.

I have no idea what he’s doing at the scene, what useful purpose he might possibly serve. Besides that he sounds quite ill. But it wasn’t up to me who to invite, and I glance down at Chanel Gilbert’s battered dead face, at her bloody nude body with its greenish discoloration and bloating in the abdominal area from bacteria and gases proliferating in her gut due to putrefaction.

The housekeeper told the police she didn’t touch the body or even get close, and I don’t doubt that Chanel Gilbert is exactly as she was found, her black silk bathrobe open, her breasts and genitals exposed. I’ve long since lost the impulse to cover a dead person’s nudity unless the scene is in a public place. I won’t change anything about the position of the body until I’m certain everyone is done with photographs and it’s time to pouch it and transport it to the CFC. That will be soon enough. Very soon as a matter of fact.

I’m sorry, I wish I could say to her as I scan puddles of blood that are a viscous dark red and drying black around the edges. Something urgent has come up. I have to leave but I’ll be back, I’d tell her if I could, and I’m vaguely aware of how loud the flies have gotten inside the foyer. With doors opening and shutting as cops come in and out of the house, flies have invaded, shimmering like drops of gasoline, alighting and crawling, looking for wounds and other orifices to lay their eggs.

My attention snaps back to the display of my phone. The image is the same. Lucy’s empty dorm room as seconds tick by. Two hundred and eighty-nine. Three hundred and ten. Now almost six minutes and there must be something coming. Who sent this to me? Not my niece. There would be no reason on earth. And why would she do it now? Why after so many years? I have a feeling I know the answer. I don’t want it to be true.

Dear God don’t let me be right. But I am. I’d have to be in total denial not to put two and two together.

“They have vegetarian sandwiches if that’s your thing,” one of the cops is saying to me.

“No thanks.” I keep waiting as I watch, and then I sense something else.

Hyde is pointing his phone at me. He’s taking a photograph.

“You’re not going to do something with that,” I say without looking up.

“I thought I’d tweet it after I Facebook it and post it on Instagram. Just kidding. You checking out a movie on your phone?”

I glance up long enough to catch him staring at me. He has that glint in his eyes, the same mischievous gleam he gets when he’s about to spitball another lamebrain quip.

“I don’t blame you for entertaining yourself,” he says. “It’s kinda dead in here.”

“I can’t do that. I’m too old-school,” the trooper says. “I need a decent size screen if I’m watching a movie.”

“My wife reads books on her phone.”

“Me too. But only when I’m driving.”

“Ha-ha. You’re a real comedian, Hyde.”

“Do you think it’s worth stringing in here? Hey Doc?”

I realize another Cambridge cop has appeared. He starts in about how to handle the blood evidence. I don’t know his name. Thinning gray hair, a mustache, short and squat, what they call a fireplug build. He doesn’t work for investigations but I’ve seen him on the Ivy League streets of Cambridge pulling people, writing tickets. One more nonessential who shouldn’t be here but it’s not for me to order cops off the scene. The body and any associated biological evidence are my jurisdiction but nothing else is. Technically.

Yes technically. Because in the main I decide what are my business and my responsibility. It’s rare I get an argument. Overall my working relationship with law enforcement is collaborative and most times they’re more than happy for me to take care of whatever I want. They almost never question me. Or at least they didn’t used to second-guess hardly anything I decided. That might be different now. I might be getting a taste of how things have changed in two short months.

“In this blood spatter class I went to they said you should string everything because you’re going to get asked in court,” the cop with thinning gray hair is saying. “If you testify that you didn’t bother with it? It looks bad to the jury. What they call the list of NO questions. The defense attorney goes through all these questions he’s sure you’ll answer no to, and it makes you look like you didn’t do your job. It makes you look incompetent.”

“Especially if the jurors watch CSI.”

“No shit.”

“What’s wrong with CSI? You don’t got a magic box in that field case of yours?”

This continues and I barely listen. I let them know that stringing would be a waste of time.

“I figured as much. Marino doesn’t see the point,” one of the cops replies.

I’m so glad Marino says it. That must make it true.

“We could bring in the total station if you want. Just reminding you we have that capability,” the trooper says to me, and then he goes on to explain about TSTs, about electronic theodolites with electronic distance meters although he doesn’t use words like that.

I know your capabilities better than you do and have handled more death scenes than you’ll ever dream of.

“Thanks but it’s not necessary,” I answer without so much as a glance at the hieroglyphics of dark bloodstains under and around the body.

I’ve already translated what I’m seeing, and using segments of string or sophisticated surveying instruments to map and connect blood streaks, swipes, sprays, splashes and droplets would offer nothing new. The area of impact is the floor under and around the body plain and simple. Chanel Gilbert wasn’t upright when she received her fatal head injuries plain and simple. She died where she is now plain and simple.

This doesn’t mean there was no foul play, far from it. I haven’t examined her for sexual assault. I haven’t done a 3-D CT scan of her body or autopsied it yet, and I go through my differential about what I’m seeing as I ask what was in her bathroom, on her bedside table.

“I’m interested in any prescription bottles for drugs. Any drugs including medications such as lenalidomide, in other words long-term nonsteroidal therapy that is immunomodulatory,” I explain. “A recent course of antibiotics also could have contributed to bacteria growth, and if it turns out she’s positive for clostridium, for example, that could help explain a rapid onset of decomposition.”

I inform them I’ve had several cases of that due to a gas-producing bacteria like clostridium where literally I saw postmortem artifacts similar to these at only twelve hours. All the while I’m going into this with the police I keep my eyes on the display of my phone.

“You talking about C. diff?” The trooper raises his voice and almost strangles on his next fit of coughing.

“It’s on my list.”

“She wouldn’t have been in the hospital for that?”

“Not necessarily if she had a mild form. Did you see antibiotics, anything back in her bedroom or bathroom that might indicate she was having a problem with diarrhea, with an infection?” I ask them.

“Gee I’m not sure I saw any prescription bottles but I did see weed.”

“What worries me is if she had something contagious,” the gray-haired Cambridge cop offers reluctantly. “I sure as hell don’t want C. diff.”

“Can you catch it from a dead body?”

“I don’t recommend contact with her feces,” I reply.

“It’s a good thing you told me.” Sarcastically.

“Keep protective clothing on. I’ll check for any meds myself and would rather see them in situ anyway. And when you get back from Dunkin’ Donuts?” I add without looking up. “Remember we don’t eat or drink in here.”

“No worries about that.”

“There’s a table in the backyard,” Hyde says. “I thought we could set up a break area out there as long as we do it before the rain comes. We got a couple of hours before the big storm they’re predicting rolls in.”

“And we know nothing happened in the backyard?” I ask him pointedly. “We know that’s not part of the scene and therefore it’s okay for us to eat and drink back there?”

“Come on, Doc. Don’t you think it’s pretty obvious she fell off a ladder here in the foyer and that’s what killed her?”

“I don’t arrive at a scene supposing anything is obvious.” I barely glance up at the three of them.

“Well I think what happened here is obvious to be honest. Of course what killed her is your department and not ours, ma’am.” The trooper chimes in like a defense attorney. Ma’am this and Mrs. that. So the jurors forget I’m a doctor, a lawyer, a chief.

“No eating, drinking, smoking or borrowing the bathrooms.” I direct this at Hyde, and I’m giving him an order. “No dropping cigarette butts or gum wrappers or tossing fast-food bags, coffee cups, anything at all into the trash. Don’t assume this isn’t a crime scene.”

“But you don’t really think it is.”

“I’m working it like one and so should you,” I answer. “Because I won’t know what really happened here until I have more information. There was a lot of tissue response, a lot of bleeding, several liters I estimate. Her scalp is boggy. There may be more than one fracture. She has postmortem changes that I wouldn’t expect. I will tell you that much but I won’t know for a fact what we’ve got here until I get her to my office. And the air-conditioning turned off during a heat wave in August? I definitely don’t like that. Let’s not be so quick to blame her death on marijuana. You know what they say.”

“About what?” The trooper looks perplexed and worried, and he and the others have backed up several more steps.

“Better to be around potheads than drunks. Booze gives you dangerous impulses like climbing ladders or driving a car or getting into fights. Weed isn’t quite so motivating. It isn’t generally known for causing aggression or risk taking. Usually it’s quite the opposite.”

“It depends on the person and what they’re smoking, right? And maybe what other meds they’re on?”

“In general that’s true.”

“So let me ask you this. Would you expect someone who fell off a ladder to bleed this much?”

“It depends on what the injuries are,” I reply.

“So if they’re worse than you think and she’s negative for drugs and alcohol, that might be a big problem is what you’re saying.”

“Whatever happened is already a big problem you ask me.” It’s the trooper again between coughs.

“Certainly it was for her. When’s the last time you had a tetanus shot?” I ask him.

“Why?”

“Because a DTaP vaccination protects against tetanus but also pertussis. And I’m concerned you might have whooping cough.”

“I thought only kids got that.”

“Not true. How did your symptoms start?”

“Just a cold. Runny nose, sneezing about two weeks ago. Then this cough. I get fits and can hardly breathe. I don’t remember the last time I had a tetanus shot to be honest.”

“You need to see your doctor. I’d hate for you to get pneumonia or collapse a lung,” I say to the trooper.

Then he and the other officers finally leave me alone.

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.