Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

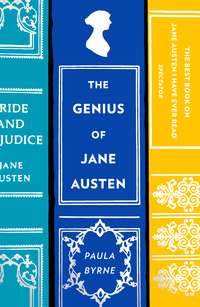

Kitabı oku: «The Genius of Jane Austen: Her Love of Theatre and Why She Is a Hit in Hollywood», sayfa 2

PART ONE

The Novelist and the Theatre

A love of the theatre is so general …

Mansfield Park

1

Private Theatricals

The fashion for private theatricals that obsessed genteel British society from the 1770s until the first part of the nineteenth century is immortalised in Mansfield Park. The itch to act was widespread, ranging from fashionable aristocratic circles to the professional middle classes and minor gentry, from children’s and apprentices’s theatricals to military and naval amateur dramatics.1

Makeshift theatres mushroomed all over England, from drawing rooms to domestic outbuildings. At the more extreme end of the theatrical craze, members of the gentrified classes and the aristocracy built their own scaled-down imitations of the London playhouses. The most famous was that erected in the late 1770s at Wargrave in Berkshire by the spendthrift Earl of Barrymore, at a reputed cost of £60,000. Barrymore’s elaborate private theatre was modelled on Vanbrugh’s King’s Theatre in the Haymarket. It supposedly seated seven hundred.2

Private theatricals performed by the fashionable elite drew much public interest, and had profound implications for the public theatres.3 On one occasion in 1787 a motion in the House of Commons was deferred because too many parliamentarians were in attendance at a private performance of Arthur Murphy’s The Way to Keep Him at Richmond House.4 Such private performances often drew more attention in the newspapers than the theatres licensed for public performance.

From an early age Jane Austen showed her own mocking awareness of what the newspapers dubbed ‘the Theatrical Ton’. In a sketch called ‘The Three Sisters’, dating from around 1792, she portrayed a greedy, self-seeking young woman who demands a purpose-built private theatre as part of her marriage settlement (MW, p. 65). In Mansfield Park, the public interest in aristocratic private theatricals is regarded ironically: ‘To be so near happiness, so near fame, so near the long paragraph in praise of the private theatricals at Ecclesford, the seat of the Right Hon. Lord Ravenshaw, in Cornwall, which would of course have immortalised the whole party for at least a twelve-month!’ (MP, p. 121). Austen carefully distinguishes between the fashionable elitist theatricals of the aristocracy, of the kind that were mercilessly lampooned by the newspapers, and those of the squirearchy.5 While Mr Yates boasts that Lord Ravenshaw’s private theatre has been built on a grand and lavish scale, in keeping with aristocratic pretensions, Edmund Bertram shows his contempt for what he considers to be the latest fad of the nobility:

‘Let us do nothing by halves. If we are to act, let it be in a theatre completely fitted up with pit, box and gallery, and let us have a play entire from beginning to end; so as it be a German play, no matter what, with a good tricking, shifting after-piece, and a figure dance, and a hornpipe, and a song between the acts. If we do not out do Ecclesford, we do nothing.’ (MP, p. 124)

Edmund’s mocking comments are directed to his elder brother. But despite Tom Bertram’s efforts to professionalise his theatre, the Mansfield theatricals eventually fall back on the measure of converting a large room of the family home into a temporary theatre for their production of Lovers’ Vows. In reality, this was far more typical of the arrangements made by the professional classes and the minor gentry who had also adopted the craze for private theatricals. The private theatricals of Fanny Burney’s uncle at Barbone Lodge near Worcester, for example, took place in a room seating about twenty people. At one end of the room was a curtained off stage for the actors, while the musicians played in an outside passage.6

In 1782, when the craze for private theatricals first reached Steventon rectory, Jane Austen was seven. The dining parlour was probably used as a makeshift theatre for the early productions.7 The first play known to have been acted by the Austen family was Matilda, a tragedy in five acts by Dr Thomas Francklin, a friend of Dr Samuel Johnson and a fashionable London preacher. The part of the tragic heroine Matilda was later popularised by Mrs Siddons on the London stage. At Steventon the tragedy was acted some time during 1782, and James Austen wrote a prologue and an epilogue for the performance.8 Edward Austen spoke the prologue and Tom Fowle, one of Mr Austen’s Steventon pupils who later became engaged to Cassandra Austen, the epilogue.9

Francklin’s dreary play, set at the time of the Norman Conquest, dramatises a feud between two brothers. Morcar, Earl of Mercia, and his brother Edwin are both in love with Matilda, the daughter of a Norman lord. Matilda has chosen Edwin. Morcar separates the lovers, sets up plans to murder his brother, and tries (unsuccessfully) to win over and marry Matilda. The tragedy takes an unexpected twist with Morcar’s unlikely reformation: he is persuaded to repent of his crimes, reunite the lovers and become reconciled to his brother.

Matilda was a surprising choice for the satirically-minded Austen family. Its long, rambling speeches and dramatic clichés of language and situation made it precisely the kind of historical tragedy that Sheridan burlesqued in The Critic. The tragedy had only six speaking parts, however, and was perhaps manageable in the dining room.10 Jane Austen was surely only a spectator at this very first Steventon performance, but it is probable that she disliked the play, given the disparaging comment she makes in her juvenilia about another historical drama, The Tragedy of Jane Shore, ‘a tragedy and therefore not worth reading’ (MW, p. 140). Perhaps the manager/actor James felt the same, for after Matilda no more tragedies were performed at Steventon.

Matilda was followed two years later by a far more ambitious project. In 1784, when Jane was nine, Sheridan’s The Rivals was acted at Steventon. Once again James Austen wrote the prologue and an epilogue for the play performed in July ‘by some young Ladies & Gentlemen at Steventon’.11 Henry spoke the prologue and the actor playing Bob Acres (possibly James himself) the epilogue. James’s prologue suggests that there was an audience for this production.12 The play has a cast of twelve, and it seems that the Austens had no qualms about inviting neighbours and friends to take part in their theatricals. The Cooper cousins and the Digweed family probably made up the numbers.13 Biographers speculate that Jane Austen may have taken the minor role of Lydia Languish’s pert maid, Lucy, but perhaps it is more likely that she was a keen spectator.14

James’s prologue is unequivocal in its praise of satirical comedy, rather than sentimental tragedy:

The Loftier members of the tragic Lyre;

Court the soft pleasures that from pity flow;

Seek joy in tears and luxury in woe.

’Tis our’s, less noble, but more pleasing task,

To draw from Folly’s features fashion’s mask;

To paint the scene where wit and sense unite

To yield at once instruction and delight.15

Jane Austen was undoubtedly influenced by her Thespian brothers, and it is therefore unsurprising that one of their favourite comic writers was to have a major impact on her own writing. While Sheridan’s influence is discernible in Austen’s earliest works, his presence can be felt most strongly in her mature works, which, unlike the juvenilia, also set out to instruct and to delight, and sought to combine ‘wit and sense’. In particular, the influence of The Rivals can be most keenly felt in Austen’s own satire on sentimentalism: her first published novel, Sense and Sensibility. It is all the more bewildering that this aspect of her comic genius has been so sorely neglected.

It was shortly after the performance of The Rivals that Cassandra and Jane were sent off to boarding school in Reading. The eccentric headmistress of the school was a Mrs La Tournelle, née Sarah Hackitt, who (much to the amusement of her pupils) could not speak a word of French. She was notorious for having a cork leg, for dressing in exactly the same clothes every day, and for her obsession with every aspect of the theatre. She enthralled her young charges with lively accounts of plays and play-acting, greenroom anecdotes, and gossip about the private lives of leading actors. Plays were performed as an integral part of the girls’ education. The Austen sisters’ interest in the drama was fostered at this school. Jane later recalled their time here with memories of fun and laughter, reminding her sister of a schoolgirl expression: ‘I could die of laughter … as they used to say at school’ (Letters, p. 5).

When the girls returned home from school for good in 1786, they were delighted to be in the company of a real French-speaking person, their exotic cousin, Eliza de Feuillide, a French countess. Eliza had taken part in theatrical activities since she was a child and had also acted in private theatricals staged by her aristocratic French friends. In a letter to Philadelphia Walter (also a cousin of Jane Austen), Eliza regaled her cousin with tales of private theatricals: ‘I have promised to spend the Carnival, which in France is the gayest Season of the year, in a very agreeable Society who have erected an elegant theatre for the purposes of acting Plays amongst ourselves, and who intend having Balls at least twice a week.’16

Family tradition records that the Steventon barn was used on occasions as a temporary theatre, but probably not until the Christmas theatricals of 1787 when Eliza was a guest at the rectory.17 In a letter written in September of that year, Philadelphia Walter wrote: ‘My uncle’s barn is fitting up quite like a theatre and all the young folks are to take their part.’18

During September 1787 Eliza had asked her cousin to join her for the Tunbridge Wells summer season, and had requested that the comedies Which is the Man?, by Hannah Cowley, and Bon Ton: or High Life Above Stairs, by Garrick, be presented at the local theatre. Much to her delight, the house was full on both occasions.19 These two modern comedies were clearly great favourites with Eliza. Bon Ton was an amusing satire on fashionable French manners, while Which is the Man? depicted a fascinating young widow, Lady Bell Bloomer, on the brink of remarriage. Eliza clearly longed for an opportunity to perform these plays at Steventon. Later, Philadelphia Walter informed her brother in a letter that these plays were to be given at Steventon that Christmas: ‘They go at Xmas to Steventon and mean to act a play Which is the Man? and Bon Ton.’20

Eliza had already made plans with the Austen family for the Christmas festivities. James was home from his foreign travels and keen to begin organising theatricals on a grander scale than before, egged on by Eliza. Both she and the Austen family wished Philadelphia to be part of the theatrical ensemble, but, like Fanny Price, the meek and timid Phila resolutely declined the offer: ‘I should like to be a spectator, but am sure I should not have courage to act a part, nor do I wish to attain it.’21 Eliza urged Phila, on behalf of the Austens, to take one of the ‘two unengaged parts’ that were waiting to be filled:

You know we have long projected acting this Christmas at Hampshire and this scheme would go on a vast deal better would you lend your assistance … and on finding there were two unengaged parts I immediately thought of you, and am particularly commissioned by My Aunt Austen and her whole family to make the earliest application possible, and assure you how very happy you will make them as well as myself if you could be prevailed on to undertake these parts and give us all your company.22

In the same letter, Eliza assured her cousin that the acting parts set aside for her were ‘neither long nor difficult’, and reminded her that the acting party were well-equipped: ‘Do not let your dress neither disturb you, as I think I can manage it so that the Green Room should provide you with what is necessary for acting.’ At the close of the letter she tried another means to persuade her shy cousin: ‘You cannot possibly resist so many pleasures, especially when I tell you your old friend James is returned from France and is to be of the acting party.’23

Eliza was clearly used to getting her own way. But Philadelphia’s firm resolve not to act surprised both Eliza and the Austen family:

I received your letter yesterday my dear friend and need not tell you how much I am concerned at your not being able to comply with a request which in all probability I shall never have it in my power to make again … I will only allow myself to take notice of the strong reluctance you express to what you call appearing in Publick. I assure you our performance is to be by no means a publick one, since only a selected party of friends will be present.24

According to Eliza, Philadelphia’s visit to Steventon was dependent on her compliance with joining the acting party: ‘You wish to know the exact time which we should be satisfied with, and therefore I proceed to acquaint you that a fortnight from New Years Day would do, provided however you could bring yourself to act, for my Aunt Austen declares “she has not room for any idle young people”.’25

Despite Eliza’s repeated assurances that the parts were very short, Philadelphia resisted her cousin’s efforts and stayed away. Eliza appears to have attributed this to Mrs Walter’s interference: ‘Shall I be candid and tell you the thought which has struck me on this occasion? – The insuperable objection to my proposal is, some scruples of your mother’s about your acting. If this is the case I can only say it is [a] pity so groundless a prejudice should be harboured in so enlightened [and so] enlarged a mind.’26 The Austens showed no such prejudice against private theatricals and Bon Ton was performed some time during this period. There is a surviving epilogue written by James.27

The first play that was presented at Steventon in 1787 was not, however, Garrick’s farce, but Susanna Centlivre’s lively comedy, The Wonder: A Woman Keeps a Secret (1714). As usual James wrote a prologue and an epilogue. The Wonder was an excellent choice for Eliza: she played the part of the spirited heroine, Donna Violante, who risks her own marriage and reputation by choosing to protect her friend, Donna Isabella, from an arranged marriage to a man she despises. The play engages in the battle-of-the-sexes debate that Eliza particularly enjoyed. Women are ‘inslaved’ to ‘the Tyrant Man’; and whether they be fathers, husbands or brothers, they ‘usurp authority, and expect a blind obedience from us, so that maids, wives, or widows, we are little better than slaves’.28

The play’s most striking feature is a saucy proposal of marriage from Isabella, though made on her behalf by Violante in disguise, to a man she barely knows. Twenty-seven years later, Jane Austen would incorporate private theatricals into her new novel, and the play, Lovers’ Vows, would contain a daring proposal of marriage from a vivacious young woman.29

The Austen family clearly had no objection whatsoever to the depiction in Centlivre’s comedy of strong, powerful women who claim their rights to choose their own husbands, and show themselves capable of loyalty and firm friendship. James’s epilogue ‘spoken by a lady in the character of Violante’ leaves us in no doubt of the Austens’ awareness of the play’s theme of female emancipation:

In Barbarous times, e’er learning’s sacred light

Rose to disperse the shades of Gothic night

And bade fair science wide her beams display,

Creation’s fairest part neglected lay.

In vain the form where grace and ease combined.

In vain the bright eye spoke th’ enlightened mind,

Vain the sweet smiles which secret love reveal,

Vain every charm, for there were none to feel.

From tender childhood trained to rough alarms,

Choosing no music but the clang of arms;

Enthusiasts only in the listed field,

Our youth there knew to fight, but not to yield.

Nor higher deemed of beauty’s utmost power,

Than the light play thing of their idle hour.

Such was poor woman’s lot – whilst tyrant men

At once possessors of the sword and pen

All female claim with stern pedantic pride

To prudence, truth and secrecy denied,

Covered their tyranny with specious words

And called themselves creation’s mighty lords –

But thank our happier Stars, those times are o’er;

And woman holds a second place no more.

Now forced to quit their long held usurpation,

Men all wise, these ‘Lords of the Creation’!

To our superior sway themselves submit,

Slaves to our charms, and vassals to our wit;

We can with ease their ev’ry sense beguile,

And melt their Resolutions with a smile.30

Jane Austen’s most expressive battle-of-the-sexes debate, that between Anne Elliot and Captain Harville in Persuasion, curiously echoes James Austen’s epilogue. Denied the ‘exertion’ of the battlefield and a ‘profession’, women have been forced to live quietly. James’s remonstrance that ‘Tyrant men [are] at once possessors of the sword and pen’ is more gently reiterated in Anne Elliot’s claim that ‘Men have had every advantage of us in telling their story … the pen has been in their hands’ (P, p. 234).

There were two performances of The Wonder after Christmas. The evident success of the play was followed up in the new year by a production of Garrick’s adaptation of The Chances (1754), for which James, once again, wrote a prologue. This play was to be Eliza’s final performance for some time.

Once again James and Henry chose a racy comedy: originally written by Beaumont and Fletcher, the play had been altered by the Duke of Buckingham and in 1754 ‘new-dressed’ by Garrick. Although Garrick had made a concerted effort to tone it down, the play was still considered to contain strong dialogue. So thought Mrs Inchbald in her Remarks, which prefaced her edition of the play: ‘That Garrick, to the delicacy of improved taste, was compelled to sacrifice much of their libertine dialogue, may well be suspected, by the remainder which he spared.’31

The Austen family did not share such compunction. Like The Wonder, Garrick’s play depicts jealous lovers, secret marriages and confused identities. The two heroines, both confusingly called Constantia, are mistaken for one another. The first Constantia is mistaken for a prostitute, although she is in fact secretly married to the Duke of Naples. It is likely that the feisty Eliza played the role of the low-born ‘second Constantia’, a favourite of the great comic actress Mrs Jordan.

Eliza had played her last role, as the return of Mr Austen’s pupils in the new year signified her imminent removal from Steventon. Both James and Henry Austen were ‘fascinated’ by the flirtatious Eliza, according to James’s son, who wrote the first memoir of Jane Austen. Most critics and biographers accept that a flirtation between Henry and Eliza was begun around this time and resulted eventually in their marriage ten years later. Some critics have conjectured that the flirtation which the young Jane Austen witnessed between Henry and Eliza during rehearsals may have given her the idea for the flirtation between Henry Crawford and Maria Bertram in Mansfield Park.32 That the young girl was acutely aware of the flirtation seems clear from one of her short tales, ‘Henry and Eliza’, where there are a series of elopements including one by Henry and Eliza, who run off together leaving only a curt note: ‘Madam, we are married and gone’ (MW, p. 36).

By all accounts, Jane Austen was an intelligent observer of the intrigues, emotions and excitement of private theatricals; of rehearsals, the reading over of scripts, and the casting of parts. James-Edward Austen’s Memoir claims that his aunt Jane ‘was an early observer, and it may be reasonably supposed that some of the incidents and feelings which are so vividly painted in the Mansfield Park theatricals are due to her recollection of these entertainments’.33

In Mansfield Park, Jane Austen devoted her creative energies to the rehearsal process rather than the performance. Furthermore the singular strength of the theatrical sequence lies in its depiction through the eyes of an envious observer. It has been suggested that in writing the Lovers’ Vows sequence Austen distilled some of her own experience as an outsider, a partially excluded younger sister.34 There is, however, no evidence to suggest that Jane was excluded from the family theatricals. Even if her youth prevented her from taking part in the actual performances, she began, at this time, to write her own short playlets. These were probably performed as afterpieces to the main play.

Henry Fielding’s outrageous burlesque The Tragedy of Tom Thumb was ‘acted to a small circle of select friends’ on 22 March 1788 at Steventon, and this was followed some time later by ‘a private Theatrical Exhibition’. Regrettably, James’s prologue to the latter gives no indication of the play performed, though it imitates Jacques’s ‘seven ages of man’ speech. The prologue also satirises the hypocrisy of the sentimental age where ‘to talk affecting, when we do not feel’ is described as a form of ‘acting’.35 The family perhaps wrote the entertainment themselves. It was probably at this time that Jane wrote and participated in her own burlesque playlet, ‘The Mystery’.36

The last plays performed at Steventon in 1788–89 were The Sultan: or A Peep into the Seraglio, a farce by Isaac Bickerstaffe, and another farce by James Townley, High Life Below Stairs. Bickerstaffe’s farce was first performed in London in 1775, but had only been recently published, in 1784. It was yet another comedy that depicted a bold, spirited heroine, posing a challenge to male prerogative and authority. Roxalana is an Englishwoman who has been captured for the Sultan’s seraglio. She displaces the favourite concubine, Elmira, by winning the honourable affections of the Sultan. Moreover, she condemns his harem and demands the freedom of all his wives: ‘You are the great Sultan; I am your slave, but I am also a free-born woman, prouder of that than all the pomp and splendour eastern monarchs can bestow.’37 James’s epilogue was yet another provocative declaration of female superiority over men, opening with the words,

Lord help us! what strange foolish things are these men,

One good clever woman is fairly worth ten.38

Two of the most popular contemporary choices for private representation were Fielding’s Tom Thumb and Townley’s High Life Below Stairs. The Burneys acted Tom Thumb in Worcestershire in 1777, ten years before the Austens chose it for performance. The part of the diminutive hero Tom Thumb was often played by a child, whose high-pitched voice would add to the comic incongruity.39

James Townley’s satire on plebeian manners, High Life Below Stairs (1759), depicts a household of lazy servants who behave as badly as their masters. They ape their masters’ manners, assume their titles, drink their expensive wine, gamble and visit the theatre. Like Gay’s Beggar’s Opera and Foote’s Mayor of Garett, Townley’s farce was a comedy that used low life to criticise high society. It was also an extremely popular choice for amateur theatricals. In part, this was because it was more prudent to poke fun at the lower orders in the safety of one’s own home than in the professional theatre house. In 1793 a performance of High Life Below Stairs in an Edinburgh public theatre incited a row between a group of highly offended footmen and their masters.

George Colman the Younger’s comedy about social transformations, The Heir at Law, was also a popular choice for the gentry to indulge themselves in stereotypical ‘low’ roles. Austen was to explore this contentious issue in Mansfield Park when the heir of Mansfield insists on staging The Heir at Law so that he can play the stage Irishman, Duberley.

Jane’s playlet, ‘The Visit’, dedicated to James, contains a quotation from High Life Below Stairs, which suggests that she composed it around the same time as the family performance of Townley’s farce, perhaps as a burlesque afterpiece. Austen repeats Townley’s phrase, ‘The more free, the more welcome’, in her play. The allusion seems to be a nod to the main play performed that day at Steventon. Austen’s habit of repeating phrases from the plays performed, or even merely contemplated for performance, at Steventon remained with her for a long time. Though Hannah Cowley’s play Which is the Man? was considered for performance, it was finally rejected. Yet Austen quoted a phrase from it in a letter dated 1810, some twenty-nine years later.40

Which is the Man? is alluded to in Austen’s ‘The Three Sisters’, written around 1788–90 (MW, p. 65). In this story, a spoilt young woman demands to play the part of Lady Bell Bloomer, just as Eliza had wished to in the 1787–88 Christmas theatricals. Again, a quotation from Cowley’s popular comedy The Belle’s Stratagem appears in a letter of 1801: ‘Mr Doricourt has travelled; he knows best’ (Letters, p. 73).

Though Eliza was now in Paris and unable to partake in the Steventon theatricals, the Cooper cousins came to Steventon for Christmas 1788–89 and Jane Cooper filled the gap left by Eliza. In a letter to Philadelphia, Eliza had hastily, though wistfully, scribbled a last message: ‘I suppose you have had pressing accounts from Steventon, and that they have informed you of their theatrical performances, The Sultan & High Life below Stairs, Miss Cooper performed the part of Roxelana [sic] and Henry the Sultan, I hear that Henry is taller than ever.’41 No prologue or epilogue by James has survived for High Life Below Stairs, but the prologue he provided for Bickerstaffe’s comedy is (confusingly) dated 1790 and states it was ‘spoken by Miss Cooper as Roxalana’.42

The Sultan and High Life Below Stairs ended the theatricals at Steventon, although there is a family tradition which claims that they were resumed in the late 1790s. The main reason why actor-manager James abandoned private theatricals seems to be that he was turning his mind to other literary interests, namely the production of a weekly magazine, The Loiterer. This periodical, like the theatricals at Steventon, was also to prove an important influence on Jane Austen’s early writings.

Henry Austen tells us in his ‘Biographical Notice’, published in the first edition of Northanger Abbey and Persuasion, that his sister Jane was acquainted with all the best authors at a very early age (NA, p. 7). The literary tastes of Catherine Morland have often been read as a parody of the author’s own literary preferences.43 Catherine likes to read ‘poetry and plays, and things of that sort’, and while ‘in training for a heroine’, she reads ‘all such works as heroines must read to supply their memories with those quotations which are so serviceable and so soothing in the vicissitudes of their eventful lives’ (NA, p. 15): dramatic works, those of Shakespeare especially, are prominent among these. Twelfth Night, Othello and Measure for Measure are singled out. Catherine duly reads Shakespeare, alongside Pope, Gray and Thompson, not so much for pleasure and entertainment, as for gaining ‘a great store of information’ (NA, p. 16).

In Sense and Sensibility, Willoughby and the Dashwoods are to be found reading Hamlet aloud together. In Mansfield Park, the consummate actor Henry Crawford gives a rendering of Henry VIII that is described by Fanny Price, a lover of Shakespeare, as ‘truly dramatic’ (MP, p. 337). Henry memorably remarks that Shakespeare is ‘part of an Englishman’s constitution. His thoughts and beauties are so spread abroad that one touches them every where’. This sentiment is reiterated by Edmund when he notes that ‘we all talk Shakespeare, use his similes, and describe with his descriptions’ (MP, p. 338). Though Emma Woodhouse is not a great reader, she is found quoting passages on romantic love from Romeo and Juliet and A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

Henry and Edmund agree on very little. It is therefore a fair assumption that, when they do concur, they are voicing the opinion of their author. Their consciousness of how Shakespeare is assimilated into our very fibre, so that ‘one is intimate with him by instinct’, reaches to the essence of Jane Austen’s own relationship with him. She would have read the plays when a young woman, but she would also have absorbed famous lines and characters by osmosis, such was Shakespeare’s pervasiveness in the culture of the age. She quotes Shakespeare from memory, as can be judged by the way that she often misquotes him. Her surviving letters refer far more frequently to contemporary plays than Shakespearean ones, but Shakespeare’s influence on the drama of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century was so thoroughgoing – for instance through the tradition of the ‘witty couple’, reaching back to Love’s Labour’s Lost and Much Ado About Nothing – that her indirect debt to his vision can be taken for granted.

In her earliest works, however, Jane Austen showed a certain irreverence for the national dramatist. Shakespeare’s history plays are used to great satirical effect in The History of England, a lampoon of Oliver Goldsmith’s abridged History of England. Austen mercilessly parodied Goldsmith’s arbitrary and indiscriminate merging of fact and fiction, in particular his reliance on Shakespeare’s history plays for supposedly authentic historical fact. Austen, by contrast, is being satirical when she makes a point of referring her readers to Shakespeare’s English history plays for ‘factual’ information about the lives of its monarchs.44 Just as solemnly, she refers her readers to other popular historical plays, such as Nicholas Rowe’s Jane Shore and Sheridan’s The Critic (MW, pp. 140, 147). The tongue-in-cheek reference to Sheridan compounds the irony, as The Critic is itself a burlesque of historical tragedy that firmly eschews any intention of authenticity.

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.