Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

Kitabı oku: «The Firm», sayfa 3

During the difficult and unpredictable days when the royal marriage was unravelling, Sir Robert Fellowes held the post of Private Secretary. It was a tough call since he was also Diana’s brother-in-law, married to Diana’s eldest sister, Jane. He was the son of the Queen’s land agent at Sandringham, and very much of the aristocratic, Old Etonian, ex-Army, ex-City, hunting, shooting, fishing brigade and therefore someone with whom the Queen was entirely comfortable. He looked ‘the part’ as John Major would say, ‘but he was never a stuffed shirt’. Others describe him as Bertie Wooster-ish, after the P. G. Wodehouse character, and to outsiders he seemed to embody so much of the stuffiness that the Princess of Wales complained about in the royal household. But as everyone who knows Sir Robert says, his looks are deceptive: he was actually a modernizer and greatly behind the move for change. He is very able, sensitive, shrewd and hugely underestimated. ‘He’s got a lot of realism, an ability to get things done, to embrace ideas even if they are not his own, and be open to suggestion,’ says a former colleague. ‘When you went into battle with him on your side you knew you might be shot on the field of battle but by the enemy, not your own team. That’s a nice feeling.’

However, for much of the time during the 1990s the Prince of Wales didn’t share the same warm feeling about his mother’s Private Secretary, and by no means always felt he was on his side. He felt that Fellowes was out to scupper him and there were times of virtual warfare between his office in St James’s Palace and Buckingham Palace, particularly over the matter of Camilla Parker Bowles. Fellowes disapproved of the Prince’s relationship with Camilla. It was his conviction that all the difficulties that had befallen the House of Windsor in recent times had been because of the Prince’s determination to hang on to Camilla, and there was a lot of truth in that.

THREE

Winds of Change

When Robert Fellowes retired in January 1999 after twenty-two years with the Queen, some of the most difficult of her reign, for a lucrative life in the City, his deputy, Sir Robin Janvrin, stepped into his shoes. Janvrin, now in his late fifties, is a departure from his predecessors, and relations with the Prince of Wales’s office have improved since his appointment. He has no landowning background, no country pile. The son of a vice admiral, he was educated at Marlborough and Brasenose College, Oxford, where he studied, fortuitously given his current job, under the constitutional historian Dr Vernon Bogdanor, who is still a good friend and useful ally. He then followed his father into the Navy for a ten-year stint before joining the Foreign Office, and in 1987, at the age of forty-one, began work in the Buckingham Palace Press Office. He is another clever man, but wears it lightly. He is cautious; he likes to think things through before making a decision, but his style is relaxed, he doesn’t panic, his colleagues love him and he has an air of normality which so many courtiers of yore never had. One could imagine him running for a bus, hanging from a strap on the underground, or washing the family car – all everyday Middle England things that if the Queen herself can’t do, then those around her certainly should.

In the late 1950s Lord Altrincham (later John Grigg, the historian and biographer) had attacked the Queen for surrounding herself by hunting, shooting and fishing types – many of whom wouldn’t have known where to find a bus. He wrote a stinging critique of the monarchy in a journal he edited called National and English Review, and, coming at a time when no one said or wrote anything derogatory about the monarchy, it caused outrage. He said it had become complacent and hidebound, that the Queen had failed to take the opportunity in this ‘New Elizabethan Age’ to make changes. His ideal was a ‘truly classless and Commonwealth Court’; George V had shaped the modern institution and borne a ‘classless stamp’, the Queen and her sister, by contrast, largely because of their conventional aristocratic education, bore ‘the debutante stamp’ and, by favouring ‘the “tweedy” sort’, bolstered the court’s ‘social lopsidedness’. He went on to attack the Queen’s speaking style, ‘which is frankly “a pain in the neck”’, and said that ‘The personality conveyed by the utterances which are put into her mouth is that of a priggish schoolgirl, captain of the hockey team, a prefect, and a recent candidate for Confirmation.’

The utterances, of course, were put into her mouth by her Private Secretary, at that time Sir Michael Adeane, who was fiercely clever but ultra-conservative and a courtier to his boot straps. He had been Assistant Private Secretary to George VI from 1937 and stayed in post with the Queen for nineteen years. However, the whole episode provided ample proof of how very influential the Private Secretary was, and still is. He determines how the sovereign’s reign is viewed by the public and ultimately posterity. He sees the Queen almost as much as her husband; they meet every morning to go through correspondence and paperwork, he briefs her on the day’s programme and the people she will meet, and they discuss anything that is relevant in the news or of constitutional or political interest. She relies upon him to be her eyes and ears and to give her sound advice and guidance.

Today the Principal Private Secretary has two deputies and one of the three of them will always be with the Queen. He will travel with her on major engagements away from the Palace and will be on duty wherever she is in residence, even during holiday periods like Christmas and Easter in case anything unforeseen happens. Robin Janvrin was on duty the night of Diana’s fatal accident in Paris. He was asleep in a cottage in the grounds at Balmoral when a call came through from the British Ambassador in Paris. It was Janvrin who had the unenviable task of breaking the news to the Queen and to the Prince of Wales, both of whom were also asleep in the castle. And it was he during the following week – which so very nearly brought about disaster – who tried to persuade the Queen to let a flag fly over Buckingham Palace. Robert Fellowes has been blamed for the failures of that week but it was the Queen, backed up by the Duke of Edinburgh, who was refusing to listen to advice. Fellowes was in London and could see at first hand what was going on outside the gates of Buckingham Palace and the damage being done by the Queen remaining silent and stoic in the Highlands.

The Queen is said to regret her delay in visiting Aberfan in 1966, recognizing with hindsight that it was a mistake not to be there immediately to comfort the grieving and express her sorrow; I suspect she regrets her instincts during that week after Diana’s death, too. Her first thoughts were for her grandsons, and for once she put family before duty. It was a mistake, however, to let the nation believe that neither she nor any other member of the Royal Family cared about the tragedy that had pole-axed the nation. She misjudged it. Shut away in Balmoral she was insulated from the real world; she couldn’t feel the raw emotion that those in the streets could feel, particularly in London around the palaces where tributes, flowers and teddy bears were being piled high. She thought that the answer to the mass hysteria was to stay calm and to keep on doing what the family had always done, safe in tradition. A flag had never flown at half mast over Buckingham Palace, not even for the death of a sovereign; it would be wrong to do it for Diana. The Queen only ever broadcast to the nation in times of national emergency and on Christmas afternoon; why speak now when Diana was no longer even a member of the Royal Family? What they all learned that week was that doing things in a certain way, because it was the way they had been done in the past, was not the safe formula they had hoped. They wisely changed, just as they had wisely changed a decade earlier.

In the mid-1980s the monarchy had hit a low patch. The honeymoon was over, both for the royal marriage and the revived fortunes of the institution. The media were becoming critical of the younger members of the family and the Labour Party was becoming ever more critical of the cost. The flash-point was It’s A Royal Knockout, a television programme aired in June 1987, which marked the Royal Family’s descent to celebrity showbiz status. It was a one-off special of the then hugely popular but very silly BBC game show It’s A Knockout. It was Edward’s idea for raising money for the Duke of Edinburgh’s Award’s 30th anniversary. The show parodied royal ceremonial and he persuaded Princess Anne, Prince Andrew and his new wife Sarah Ferguson, the Duchess of York, to join him in dressing up in mock Tudor costume and making complete fools of themselves alongside celebrities like Barbara Windsor, Les Dawson and Rowan Atkinson. The ratings soared through the roof and the event raised over £1 million, which was divided between the Award, Save the Children, the World Wildlife Fund and the International Year of Shelter for the Homeless. But it came at a terrible price for the dignity of the monarchy. To make matters worse, at a press conference afterwards, as embarrassed journalists tried to find some way of being polite when asked what they had thought of it, twenty-three-year-old Edward, at that time very arrogant, lost his temper and stormed petulantly out of the tent. The following day’s newspapers led with the inevitable headline ‘It’s A Royal Walkout’.

It is incidents like this that have cemented attitudes over the years. Prince Edward has never been allowed to forget his mistake and understandably he resents the press as a result which simply reinforces the impression that he is arrogant, and it becomes a vicious circle.

Princess Margaret was always perceived as spoilt because of her behaviour when she was young and that label stuck, yet the people who knew her say while she could be imperious, she was actually very kind and caring. Prince Philip is thought of as a reactionary old fool who always puts his foot in it. He has made some howlers in his time, there is no escaping it, but he is about as foolish as a fox. History will show him to have made a very serious contribution to the success of the Queen’s reign – as well having been a prime mover in the field of conservation. Yet whenever he makes a joke that falls flat – usually done in an attempt to put some stranger at their ease – out comes the catalogue of blunders from the past and suggestions from some nonentity of an MP that he should stay out of public life. The Prince of Wales once admitted to talking to his plants and has been ridiculed as the loony Prince by his detractors ever since. Princess Anne is about the only one who has managed to turn round her early image and having once been one of the most unpopular members of the Royal Family is now seen as one of the hardest working and best liked.

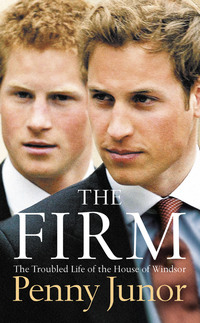

It will be interesting to see whether Prince Harry will be able to shake off the labels that have already been attached to him. Of all his misdemeanours, choosing a Nazi outfit to wear to a friend’s fancy dress party in January 2005 was the most idiotic. The underage drinking, the partying, the marijuana, the girls, even taking a punch at a photographer outside a London nightclub were forgivable. He was young, not thinking, he’s had an unsettled childhood; any or all of these could have happened to any teenager or twenty-year-old. As could the Nazi episode. Today’s young are blissfully unaware of history (some of them aren’t even taught it in our schools). None of his contemporaries at the party noticed anything wrong, and the person who sent the photos to the Sun hadn’t even realized the significance. They thought the interesting picture was the one of Prince William dressed as a lion.

The problem is that Harry isn’t just any twenty-year-old. He may not feel any different from his mates but he can’t afford to behave like them. He is third in line to the throne and, like it or not, he is living in a goldfish bowl. Wherever he goes – even to the most private of parties – where there is a mobile phone, there is a camera. And after this the tabloids will be sitting with cheque books open waiting for the next cracking picture. They have had Harry tailed in the past and they can do it again; it may not be fair but it sells newspapers and some of those are always happy to have a pop at the monarchy.

During the eighties there were two key people in the household who realized that if there was to be a secure future change was imperative. Both were newly in post. In December 1984, David, the thirteenth Earl of Airlie, had become Lord Chamberlain in place of Lord ‘Chips’ Maclean, twenty-seventh chief of Clan Maclean, the last in a long tradition of well-bred amateurs. David Airlie may have been aristocratic, and with a family castle and sixty-nine thousand acres in Scotland he was undoubtedly ‘tweedy’, and he may have been a Scots Guard for five years, but he was no amateur. He was a highly successful merchant banker with thirty-five years’ experience – he had just stepped down as chairman of Schroders when he came to the Palace – and, according to one colleague, was ‘marvellous, canny, and a wise businessman’. Better still, he was an old friend of the Queen – they are less than four weeks apart in age and have known each other all their lives. His family home was five miles from Glamis Castle, where the Queen Mother grew up, his wife, Virginia, was and still is one of the Queen’s ladies-in-waiting, and his younger brother was Sir Angus Ogilvy, who sadly died recently but who was married to the Queen’s cousin, Princess Alexandra. He was just what the House of Windsor needed: a delightful, wise and down-to-earth man who could gently steer the monarchy away from the treacherous rocks towards which it was surely headed.

Two years later Sir Philip Moore retired as Private Secretary – the last of the ancien régime – and was replaced by Bill Heseltine, who had been patiently waiting in the wings. He was the Australian who had succeeded Commander Richard Colville as Press Officer at the end of the 1960s and revolutionized the Palace’s relationship with the media. The two men were of one mind: the growing criticism had to be addressed; the world had moved on – just about every other major company and business in the Western world had reorganized itself; streamlined, modernized and introduced best practices. The Firm needed to be firmly nudged into the twentieth century.

It was George VI who first referred to the House of Windsor as The Firm and the name stuck – although some have called it Monarchy plc – and when David Airlie was appointed it was still run along lines that George VI and probably even Queen Victoria a century earlier, would have recognized and felt comfortable with.

When Michael Colborne, a naval chief petty officer, arrived to look after the Prince of Wales’s office in 1979, he was the only person at his level in the Palace who had not been to a major public school. ‘If you didn’t go to the right school you didn’t fit; you didn’t speak the language. It could be very uncomfortable for people like me. They called me the “Rough Diamond”. I lived there for six months and I felt so lonely in the Palace.’

‘It was all rather stuck in the mud, in a time warp,’ remembers someone else. ‘The Palace was still recruiting from certain sections of society and the Queen hadn’t been particularly well served. There was a country house atmosphere; things were being done in the same way they’d been done for twenty, thirty or nearer a hundred years – since Prince Albert’s time probably. There were some excellent individuals there, who had no doubt wanted to move things forward a bit, but there had never been the concerted pressure to do it.’

David Airlie provided that pressure. He already had experience of modernizing companies and had learned lessons in the process which were invaluable in the mammoth task before him at Buckingham Palace. He had done it at General Accident and Schroders, in both cases bringing in outside consultants to report on whether best practices were being followed; he recommended to the Queen that they go down the same route. And so in February 1986, by which time he had a good idea of what needed to be done – and it included first and foremost getting rid of excessive government interference – he called in the City accountancy firm Peat Marwick McLintock, who were already the Palace auditors, to overhaul the finances and look at the workings of the household from top to bottom. He was anxious that the Treasury should take the findings seriously and Peat Marwick had the necessary clout to impress them. It was vital, he felt, for the report to be paid for and carried out internally and not financed by government money; the Treasury could see the report but they were not to be involved. The man who conducted the study was Michael Peat, a partner in the family firm then in his mid-thirties. His father, Sir Gerrard Peat, had been auditor and assistant auditor to the Queen’s Privy Purse since 1969 and Michael had frequently worked alongside him in the past so was already familiar with the Palace’s finances, and, crucially, already knew David Airlie.

It was a major undertaking which took a full year, but in 1987 Peat came up with a report that ran to 1383 pages, with no fewer than 188 recommendations for change. They were wide-ranging but fundamentally changed the working practices of every department in the Palace, from the dining arrangements to the way in which the private secretaries operated.

Michael Peat gives all the credit to David Airlie, on the grounds that identifying what was wrong was the easy bit; persuading the Queen and everyone else in the Royal Family and the household to accept it and to agree to change, was quite another matter. And, to his lasting credit, David Airlie achieved it, although he is equally modest and says that Michael Peat was the mastermind. In truth they were a formidable double act who both became extremely unpopular in the process. It was an unhappy time in the Palace with everyone uncertain about their future. One of Airlie’s stipulations was that there would be no job losses – natural wastage yes, but no one would find themselves out of a job. That was paramount because he could not put the Queen in a position where she had to sack people – they couldn’t afford bad publicity during this process – but there was a lot of uncertainty and edginess nevertheless and a feeling that each department was the next for change. But between them they achieved what many thought was the impossible.

FOUR

188 Recommendations

I can’t help thinking about A. A. Milne again and his wonderful poem, ‘The King’s Breakfast’ in which the King laments the lack of butter on his breakfast table. He isn’t a fussy man but he knows what he likes. And so he tells the Queen and the Queen tells the dairymaid who goes to tell the cow. But the cow wants to go to sleep and suggests he try marmalade on his bread instead of butter. So back goes the suggestion from the cow to the dairymaid and the dairymaid to the Queen and from the Queen to the King. But the King is forlorn and sobs and whimpers and when the news reaches the cow, via the Queen and the dairymaid, the cow relents and gives him milk as well as butter. And the King is so delighted he does a little jig.

I am not sure that the dairymaid actually attended the royal breakfast before Lord Airlie called in Peat Marwick McLintock to see how Buckingham Palace might be modernized, but the royal household was certainly overrun with flunkies – ‘Why have I got so many footmen?’ the Queen was said to have asked when she saw the report. And whether A. A. Milne knew it or not, milk and butter for the royal breakfast does come from a royal herd of Jersey cows in Windsor Great Park, delivered to the Palace each morning before dawn.

The Palace dining arrangements were definitely in need of an overhaul and Peat and Airlie discussed them but decided this was one change too far for the immediate future. In the grand scheme of things, five tiers of dining and waiting staff in tailcoats was a mere detail compared with the other 188 problems they had earmarked for change, and they feared that coming between their colleagues and their comestibles might be the straw that broke the camel’s back.

It was a very quaint system nonetheless and one which was only changed a couple of years ago. The most senior members of the household ate in the grandest dining room; that included the Lord Chamberlain, the private secretaries, the Master of the Household, ladies-in-waiting, press secretaries, and chaplains, senior Women of the Bedchamber, the Mistress of the Robes and the Keeper of the Privy Purse. A second dining room was the province of senior officials such as the assistants to the Master of the Household, the Chief Housekeeper and the Paymaster. Then there was one for the officials – secretaries and assistants, clerks, press officers, typists and administrative personnel. Next rung down were the stewards: pages, yeomen, the Queen’s dressers and her chauffeur. And below stairs – in the basement – was the fifth and final dining room for the most junior members of the domestic staff: under-butlers, footmen, chefs, maids, porters, postmen, plumbers, gardeners, grooms and chauffeurs.

The first summer the Palace was opened to the public, the most senior of the dining rooms was given over to the summer opening administrative staff which involved some very unpopular rearrangements. The occupants of that room took over the room belonging to the next tier down, and they in turn were forced to double up with the junior staff in the basement. Some of them had never ventured into the basement and so many got lost en route that they had to put up signs to direct them. August was not a happy month.

When change finally came, in June 2003, the four dining rooms were reduced to two. The household continues to eat separately, except during the summer opening and on a few other occasions, and everyone else has a snazzy new self-service restaurant. There is also a separate room with comfortable chairs for coffee and tea which is also open to every grade of employee. Since so many work shifts and odd hours it was the only sensible solution, and in a stroke attacked the rigid hierarchy that most enlightened companies abandoned years ago.

The organizational structure Lord Airlie discovered inside Buckingham Palace when he arrived there as Lord Chamberlain in 1984 was unique. And although he implemented well over 160 of 188 recommendations for change to make it more efficient and businesslike – including the role of the Lord Chamberlain – it remains unique to this day. Nothing compares, and yet the monarchy is more of a business today than it ever was in previous reigns. In a typical company you have a chairman, a chief executive who reports to the chairman, and four or five departmental heads who report to the chief executive. All of these posts exist in the royal household, by one name or another, but in the final analysis the Queen is the one who makes the decisions about the day-to-day affairs and so the departmental heads have direct access to the Queen over the head of the Lord Chamberlain. ‘The Lord Chamberlain is a sort of hands-on chairman of a company with one shareholder’ is the way it was described to me. The departmental heads do report to him and he chairs regular meetings with them all, but he does not get involved in the detail of whether the Queen goes to New Zealand or Birmingham, who she invites to lunch or which state coach she uses for a state visit. Before Lord Airlie took up the post there was no cohesion at the top of the household, no communication and no reporting structure, and although it is still not set in stone because of the Queen’s role in the decision-making process, it is a lot more efficient than it was before.

The names of the posts, however, are still from another era. The Lord Chamberlain is not, as the name might suggest, in charge of the Lord Chamberlain’s Office. That is the Comptroller’s job – currently held by Lieutenant Colonel Sir Malcolm Ross, a thoroughly charming old Etonian of sixty plus, who spent twenty-three years in the Scots Guards and the remainder of his career in the royal household. He is a wonderful product of the two and perfect for the job of running the ceremonial side of the monarchy, which he does except when there are ‘issues of import’ such as the Princess of Wales’s funeral to be arranged. In that event, the Lord Chamberlain swings into action and takes charge of the Lord Chamberlain’s Office, which is where you would have expected him to be in the first place.

Once he had completed the report, Lord Airlie arranged for Michael Peat to stay on at the Palace for the next three years to help him develop and implement the recommendations Peat had made. The two men had worked very closely together during the writing of the report and got on well together; Airlie’s past experience at Schroders and General Accident had taught him that it was vital for the chairman to work closely with the consultant. Airlie knew that many of Peat’s ideas would never fly and he was able to say so right away and eliminate unnecessary work. The entire thing was the art of the possible and some reforms had to be sacrificed in the interests of progressing more important ones.

Among the most important was sorting out the Civil List. This is the sum voted by Parliament to pay for the sovereign in carrying out her duties as Head of State, and for the running of the royal household. It is much misunderstood and has caused more grief over the years to the monarchy than anything else. It is worth putting the cost into perspective. The monarchy costs £36.8 million a year to run; the Atomic Physics Particle Research Laboratory, by comparison, costs about £100 million, the Welsh fourth television channel (S4C) about £74 million a year, the British Museum about £40 million. But where the comparison falls down is that the last three are paid for by the taxpayer, and the taxpayer doesn’t actually pay for the monarchy at all. It is paid for by the revenue that comes from the Crown Estates. The taxpayer doesn’t pay a penny. After the Norman Conquest in 1066 all the lands of England belonged to William the Conqueror and he and his successors received the rent and profits from the land, which they used to finance the government. Over the years monarchs sold bits of land or gave away large estates to nobles and barons in return for military service until, by 1702 (historians must forgive me for simplifying the story), there wasn’t enough income from what remained to pay for the cost of the government (which had grown in the intervening seven hundred years) and the royal household. Parliament therefore introduced an Act to stop the Crown selling off more of its land, and took over management of the estates. When George III came to the throne in 1760 he relinquished his right to the revenue in return for a fixed annual sum of money from Parliament, which became known as the Civil List. The Crown Estate still belongs to the sovereign ‘in the right of the Crown’, which means it is not her private property, but at the beginning of each reign the new sovereign traditionally hands over the revenue from the Crown Estate to the Exchequer for his or her lifetime.

It is a huge business. The Estate owns more than 250,000 acres of agricultural land throughout England and Scotland: 7500 acres of forestry at Windsor, another 7500 at Glenlivet, more in Somerset and smaller amounts elsewhere; and it owns Windsor Great Park – a further 5313 acres which includes Ascot Racecourse. It also has urban estates, mostly in central London – residential property in Regent’s Park, Kensington and Millbank; and commercial property in Regent Street, Victoria Street and in the City, including the site of the Royal Mint. It also owns more than half of the United Kingdom’s foreshore and almost all the seabed to a limit of twelve miles from the shore, which is used for everything from marine industries to leisure activities.

All of this is run by a Board of Commissioners which employs experts in various fields of estate management, and under the Crown Estate Act of 1961 has a duty to maintain and enhance the value of the Estate. Management fees are taken out of the revenue, but the remainder – about £150 million – goes to the Treasury. Thirty-six million pounds from that sum is paid to the Queen, and the government pockets the rest to meet general government expenditure.

Even with my limited grasp of mathematics, the Queen is not the leech we have been led to believe. She does not cost the country a brass farthing, but is actually saving the taxpayer something like £114 million. If that money wasn’t coming from the Crown Estate you can bet your boots it would come from the taxpayer, and, indeed, if the Queen went mad and splashed out on a new aircraft, or a flashy new coach and spent too much the taxpayer would have to pay more for the shortfall. Parliament decides how much money the sovereign should have, and in that respect acts like a trustee of an old family trust, which in a constitutional monarchy is just as it should be. Parliament needs to make sure the Queen isn’t more of a financial burden than she has to be, not because it has to pay for her if she is, but because the more money there is left over after paying the Civil List, the more there is for general expenditure.

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.