Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

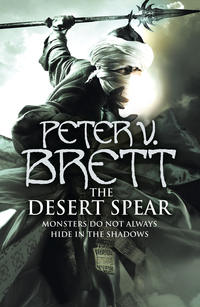

Kitabı oku: «The Desert Spear», sayfa 2

CHAPTER 2 ABBAN

305–308 AR

JARDIR WAS NINE WHEN the dal’Sharum took him from his mother. It was young, even in Krasia, but the Kaji tribe had lost many warriors that year and needed to bolster their ranks lest one of the other tribes attempt to encroach on their domain.

Jardir, his three younger sisters, and their mother, Kajivah, shared a single room in the Kaji adobe slum by the dry well. His father, Hoshkamin, had died in battle two years before, slain in a well raid by the Majah tribe. It was customary for one of a fallen warrior’s companions to take his widows as wives and provide for his children, but Kajivah had given birth to three daughters in a row, an ill omen that no man would bring into his household. They lived on a small stipend of food from the local dama, and if they had nothing else, they had each other.

“Ahmann asu Hoshkamin am’Jardir am’Kaji,” Drillmaster Qeran said, “you will come with us to the Kaji’sharaj to find your Hannu Pash, the path Everam wills for you.” He stood in the doorway with Drillmaster Kaval, the two warriors tall and forbidding in their black robes with the red drillmaster veils. They looked on impassively as Jardir’s mother wept and embraced him.

“You must be man for our family now, Ahmann,” Kajivah told him, “for me and your sisters. We have no one else.”

“I will, Mother,” Jardir promised. “I’ll become a great warrior and build you a palace.”

“Of that, I have no doubt,” Kajivah said. “They say I was cursed, to bear three girls after you, but I say Everam blessed our family with a son so great, he needed no brothers.” She hugged him tightly, her tears wet on his cheek.

“Enough weeping,” Drillmaster Kaval said, taking Jardir’s arm and pulling him away. Jardir’s young sisters stared as they led him from the tiny apartment.

“It is always this way,” Qeran said. “Mothers can never let go.”

“She has no man to care for her,” Jardir replied.

“You were not told to speak, boy,” Kaval barked, cuffing him hard on the back of the head. Jardir bit back a cry of pain as his knee struck the sandstone street. His heart screamed at him to strike back, but he checked himself. However much the Kaji might need warriors, the dal’Sharum would kill him for such an affront with no more thought than a man might give to squashing a scorpion under his sandal.

“Every man in Krasia cares for her,” Qeran said, jerking his head back toward the door, “spilling blood in the night to keep her safe as she weeps over her sorry excuse for a son.”

They turned down the street, heading toward the Great Bazaar. Jardir knew the way well, for he went to the market often, though he had no money. The scents of spice and perfume were a heady mix, and he liked to gaze at the spears and wicked curved blades in the armorers’ kiosks. Sometimes he fought with other boys, readying himself for the day he would be a warrior.

It was rare for dal’Sharum to enter the bazaar; such places were beneath them. Women, children, and khaffit scurried out of the drillmasters’ path. Jardir watched the warriors carefully, doing his best to imitate their carriage.

Someday, he thought, it will be my path that others scramble to clear.

Kaval checked a chalked slate and looked up at a large tent, streaming with colored banners. “This is the place,” he said, and Qeran grunted. Jardir followed as they lifted the flap and strode inside without bothering to announce themselves.

The inside of the tent smelled of incense smoke, and it was richly carpeted, filled with piles of silk pillows, racks of hanging carpets, painted pottery, and other treasures. Jardir ran a finger along a bolt of silk, shivering at its smoothness.

My mother and sisters should be clad in such cloth, he thought. He looked at his own tan pantaloons and vest, grimy and torn, and longed for the day he could don a warrior’s blacks.

A woman at the counter gave a shriek as she caught sight of the drillmasters, and Jardir looked up at her just as she pulled her veil over her face.

“Omara vah’Haman vah’Kaji?” Qeran asked. The woman nodded, eyes wide with fear.

“We have come for your son, Abban,” Qeran said.

“He’s not here,” Omara said, but her eyes and hands, the only parts of her visible beneath the thick black cloth, trembled. “I sent him out this morning, delivering goods.”

“Search the back,” Qeran told Kaval. The drillmaster nodded and headed for the dividing flap behind the counter.

“No, please!” Omara cried, stepping in his path. Kaval ignored her, shoving her aside and disappearing into the back. There were more shrieks, and a moment later the drillmaster reemerged clutching the arm of a young boy in a tan vest, cap, and pantaloons—though of much finer cloth than Jardir’s. He was perhaps a year or two older than Jardir, stocky and well fed. A number of older girls followed him out, two in tans and three more in the black, open-faced headwraps of unmarried women.

“Abban am’Haman am’Kaji,” Qeran said, “you will come with us to the Kaji’sharaj to find your Hannu Pash, the path Everam wills for you.” The boy trembled at the words.

Omara wailed, grabbing at her son, trying to pull him back. “Please! He is too young! Another year, I beg!”

“Silence, woman,” Kaval said, shoving her to the floor. “The boy is old and fat enough as it is. If he is left to you another day, he will end up khaffit like his father.”

“Be proud, woman,” Qeran told her. “Your son is being given the chance to rise above his father and serve Everam and the Kaji.”

Omara clenched her fists, but she stayed where she had landed, head down, and wept quietly. No woman would dare defy a dal’Sharum. Abban’s sisters clutched at her, sharing in her grief. Abban reached for them, but Kaval jerked him away. The boy cried and wailed as they dragged him out of the tent. Jardir could hear the women crying even after the heavy flap fell closed and the clamor of the market surrounded them.

The warriors all but ignored the boys as they led the way to the training grounds, letting them trail after. Abban continued to weep and shake as they went.

“Why are you crying?” Jardir asked him. “The road ahead is bright with glory.”

“I don’t want to be a warrior,” Abban said. “I don’t want to die.”

Jardir shrugged. “Maybe you’ll be called to be dama.”

Abban shuddered. “That would be worse. A dama killed my father.”

“Why?” Jardir asked.

“My father accidentally spilled ink on his robe,” Abban said.

“The dama killed him just for that?” Jardir asked.

Abban nodded, fresh tears welling in his eyes. “He broke my father’s neck right then. It happened so fast…he reached out, there was a snap, and my father was falling.” He swallowed hard. “Now I’m the only man left to look out for my mother and sisters.”

Jardir took his hand. “My father’s dead, too, and they say my mother’s cursed for having three daughters in a row. But we are men of Kaji. We can surpass our fathers and bring honor back to our women.”

“But I’m scared,” Abban sniffed.

“I am, too, a little,” Jardir admitted, looking down as he said it. A moment later, he brightened. “Let’s make a pact.”

Abban, raised in the cutthroat business of the bazaar, looked at him suspiciously. “What kind of pact?”

“We’ll help each other through Hannu Pash,” Jardir said. “If you stumble, I will catch you, and if I fall, you,” he smirked and slapped Abban’s round belly, “will cushion it.”

Abban yelped and rubbed his belly, but he did not complain, looking at Jardir in wonder. “You mean that?” he asked, drying his eyes with the back of his hand.

Jardir nodded. They were walking in the shade of the bazaar’s awnings, but he grabbed Abban’s arm and pulled him into the sunlight. “I swear it by Everam’s light.”

Abban smiled widely. “And I swear it by the jeweled Crown of Kaji.”

“Keep up!” Kaval barked, and they chased after, but Abban moved with confidence now.

The drillmasters drew wards in the air as they passed the great temple Sharik Hora, mumbling prayers to Everam, the Creator. Beyond Sharik Hora lay the training grounds, and Jardir and Abban tried to look everywhere at once, taking in the warriors at their practice. Some worked with shield and spear or net, while others marched or ran in lockstep. Watchers stood upon the top rungs of ladders braced against nothing, honing their balance. Still more dal’Sharum hammered spearheads and warded shields, or practiced sharusahk—the art of empty-handed battle.

There were twelve sharaji, or schools, surrounding the training grounds, one for each tribe. Jardir and Abban were Kaji tribe, and thus were taken to the Kaji’sharaj. Here they would begin the Hannu Pash and emerge as dama, dal’Sharum, or khaffit.

“The Kaji’sharaj is so much larger than the others,” Abban said, looking up at the huge pavilion tent. “Only the Majah’sharaj is even close.”

“Of course it is,” Kaval said. “Did you think it coincidence that our tribe is named Kaji, after Shar’Dama Ka, the Deliverer? We are the get of his thousand wives, blood of his blood. The Majah,” he spat, “are only the blood of the weakling who ruled after the Shar’Dama Ka left this world. The other tribes are inferior to us in every way. Never forget that.”

They were taken into the pavilion and given bidos—simple white loincloths—and their tans were taken to be burned. They were nie’Sharum now; not warriors, but not boys, either.

“A month of gruel and hard training will burn the fat from you, boy,” Kaval said as Abban removed his shirt. The drillmaster punched Abban’s round belly in disgust. Abban doubled over from the blow, but Jardir caught him before he fell, steadying him until he caught his breath. When they were finished changing, the drillmasters took them to the barrack.

“New blood!” Qeran shouted as they were shoved into a large, unfurnished room filled with other nie’Sharum. “Ahmann asu Hoshkamin am’-Jardir am’Kaji, and Abban am’Haman am’Kaji! They are your brothers now.”

Abban colored, and Jardir knew immediately why, as did every other boy present. By leaving out his father’s name, Qeran had as much as announced that Abban’s father was khaffit—the lowest and most despised caste in Krasian society. Khaffit were cowards and weaklings, men who could not hold to the warrior way.

“Ha! You bring us a fat pig-eater’s son and a scrawny rat!” the largest of the nie’Sharum cried. “Throw them back!” The other boys all laughed.

Drillmaster Qeran growled and punched the boy in the face. He hit the stone floor hard, spitting up a gob of blood. All laughing ceased.

“Make mock when you have lost your bido, Hasik,” Qeran said. “Until then, you are all scrawny, pig-eating khaffit rats.” With that, he and Kaval turned on their heels and strode out.

“You’ll pay for that, rats,” Hasik said, the last word ending in a strange whistle. He tore the loose tooth from his mouth and threw it at Abban, who flinched when it struck. Jardir stepped in front of him and snarled, but Hasik and his cohorts had already turned away.

Soon after they arrived, they were given bowls, and the gruel pot was set out. Famished, Jardir went right for the pot, and Abban hurried even faster, but one of the older boys blocked their path. “You think you eat before me?” he demanded. He shoved Jardir into Abban, and they both fell to the floor.

“Get up, if you mean to eat,” said the drillmaster who had brought the gruel. “The boys at the end of the line go hungry.”

Abban shrieked, and they scrambled to their feet. Already most of the boys had lined up, roughly in order of size and strength, with Hasik at the very front. At the back of the line, the smallest boys fought fiercely to avoid the spots at the end.

“What are we going to do?” Abban asked.

“We’re going to get on that line,” Jardir said, grabbing Abban’s arm and dragging him toward the center, where the boys were still outweighed by well-fed Abban. “My father said that weakness shown is worse than weakness felt.”

“But I don’t know how to fight!” Abban protested, shaking.

“You’re about to learn,” Jardir said. “When I knock someone down, fall on him with all your weight.”

“I can do that,” Abban agreed. Jardir guided them right up to a boy who snarled in challenge. He puffed out his chest and faced up against Abban, the larger of the two boys.

“Get to the back of the line, new rats!” he growled.

Jardir said nothing, punching the boy in the stomach and kicking at his knees. When he fell, Abban took his cue, falling on the boy like a sandstone pillar. By the time Abban got up, Jardir had already taken the boy’s place in line. He glared at those behind, and they made room for Abban, as well.

A single ladle of gruel slopped into their bowls was their reward. “That’s it?” Abban asked in shock. The server glared at him, and Jardir quickly ushered him away. The corners of the room had already been taken by the older boys, so they retreated to one of the walls.

“I’ll starve on this,” Abban said, swirling the watery gruel in his bowl.

“We’re still better off than some,” Jardir said, pointing to a pair of bruised boys with nothing to eat at all. “You can have some of mine,” he added when Abban did not brighten. “I never got much more than this at home.”

They slept on the sandstone floor of the barrack, thin blankets their only shield against the cold. Used to sharing the warmth of his mother and sisters, Jardir nestled against Abban’s warm bulk. In the distance, he heard the Horn of Sharak, and knew battle was being joined. It took a long time for him to drift off, dreaming of glory.

He woke with a start when another of the thin blankets was thrown over his face. He struggled hard, but the cloth was twisted behind his head and held tight. He heard Abban’s muffled scream next to him.

Blows began to rain down on him from all sides, kicks and punches blasting the breath from his body and rattling his brains. Jardir flailed his limbs wildly, but though he felt several of his blows connect, it did nothing to lessen the onslaught. Before long, he was hanging limply, supported wholly by the suffocating blanket.

When he thought he could endure no more and must surely die, never having gained paradise or glory, a familiar voice said, “Welcome to the Kaji’sharaj, rats,” the s at the end whistling through Hasik’s missing tooth. The blankets were released, dropping them to the floor.

The other boys laughed and went back to their blankets as Jardir and Abban curled tight and wept in the darkness.

“Stand up straight,” Jardir hissed as they awaited morning inspection.

“I can’t,” Abban whined. “Not a bit of sleep, and I ache to my bones.”

“Don’t let it show,” Jardir said. “My father said the weakest camel draws the wolves.”

“Mine told me to hide until the wolves go away,” Abban replied.

“No talking!” Kaval barked. “The dama is coming to inspect you pathetic wretches.”

He and Qeran took no notice of their cuts and bruises as they walked past. Jardir’s left eye was swollen nearly shut, but the only thing the drillmasters noticed was Abban’s slump. “Stand straight!” Qeran said, and Kaval punctuated the command with a crack of his leather strap across Abban’s legs. Abban screamed in pain and nearly fell, but Jardir steadied him in time.

There was a snicker, and Jardir snarled at Hasik, who only smirked in response.

In truth, Jardir felt little steadier than Abban, but he refused to show it. Though his head spun and his limbs ached, Jardir arched his back and kept his good eye attentive as Dama Khevat approached. The drillmasters stepped aside for the cleric, bowing in submission.

“It is a sad day that the warriors of Kaji, the bloodline of Shar’Dama Ka, the Deliverer himself, should be reduced to such a sorry lot,” the dama sneered, spitting in the dust. “Your mothers must have mixed camel’s piss with the seeds of men.”

“That’s a lie!” Jardir shouted before he could help himself. Abban looked at him incredulously, but it had been an insult past his ability to bear. As Qeran sprang at him with frightening speed, Jardir knew he’d made a grave mistake. The drillmaster’s strap laid a line of fire where it struck his bare skin, knocking him to the ground.

But the dal’Sharum did not stop there. “If the dama tells you that you are the son of piss, then it is so!” he shouted, whipping Jardir repeatedly. Clad only in his bido, Jardir could do nothing to ward off the blows. Whenever he twisted or turned to protect a wounded area, Qeran found a fresh patch of skin to strip. He screamed, but it only encouraged the assault.

“Enough,” Khevat said. The blows stopped instantly.

“Are you the son of piss?” Qeran asked.

Jardir’s limbs felt like wet bread as he forced himself to his feet. He kept his eyes on the strap, raised and ready to strike again. He knew if he continued his insolence, the drillmaster would kill him. He would die with no glory, and his spirit would spend millennia outside the gates of paradise with the khaffit, looking in at those in Everam’s embrace and waiting for reincarnation. The thought terrified him, but his father’s name was the only thing he owned in the world, and he would not forsake it.

“I am Ahmann, son of Hoshkamin, of the line of Jardir,” he said as evenly as he could manage. He heard the other boys gasp, and steeled himself for the attack to come.

Qeran’s face contorted in rage, and he raised the strap, but a slight gesture from the dama checked him.

“I knew your father, boy,” Khevat said. “He stood among men, but he won no great glory in his short life.”

“Then I’ll win glory for both of us,” Jardir promised.

The dama grunted. “Perhaps you will at that. But not today. Today you are less than khaffit.” He turned to Qeran. “Throw him in the waste pits, for true men to shit and piss upon.”

The drillmaster smiled, punching Jardir in the stomach. When he doubled over, Qeran grabbed him by his hair and dragged him toward the pits. As he went, Jardir glanced at Hasik, expecting another smirk, but the older boy’s face, like all the assembled nie’Sharum, was a mix of disbelief and ashen fear.

“Everam saw the cold blackness of Nie, and felt no satisfaction there. He created the sun to give light and warmth, staving off the void. He created Ala, the world, and set it spinning around the sun. He created man, and the beasts to serve him, and watched as His sun gave them life and love.

“But for half its time, Ala faced the dark of Nie, and Everam’s creatures were fearful. So He made the moon and stars to reflect the sun’s light, a reminder in the night that they had not been forgotten.

“Everam did this, and He was satisfied.

“But Nie, too, had a will. She looked upon creation, marring Her perfect blackness, and was vexed. She reached out to crush Ala, but Everam stood fast, and Her hand was stayed.

“But Everam had not been quick enough to stave off Nie’s touch completely. The barest brush of Her dark fingers grew on His perfect world like a plague. The inky blackness of Her evil seeped across the rocks and sand, blew on the winds, and was an oily stain on Ala’s pure water. It swept across the woods, and the molten fire that bubbled up from beneath the world.

“And in those places, alagai took root and grew. Creatures of the blackness, their only purpose to uncreate; killing Everam’s creatures their only joy.

“But lo, the world turned, and the sun shone light and warmth across Nie’s creatures of cold dark, and they were undone. The life-giver burned away their unlife, and the alagai screamed.

“Desperate to escape, they fled to the shadows, oozing deep into the world, infecting its very core.

“There, in the dark abyss at the heart of creation, grew Alagai’ting Ka, the Mother of Demons. Handmaiden of Nie Herself, she waited only for the world to turn that she might send her children forth again to ravage creation.

“Everam saw this, and reached out His hand to purge the evil from His world, but Nie stood fast, and His hand was stayed.

“But He, too, touched the world one last time, giving men the means to turn alagai magic against itself. Giving them wards.

“Locked then in a struggle for the sake of all He had made, Everam had no choice but to turn His back on the world and throw Himself fully upon Nie, struggling endlessly against Her cold strength.

“And as above, so below.”

Every day of Jardir’s first month in sharaj was the same. At dawn, the drillmasters brought the nie’Sharum out into the hot sun to stand for hours as the dama spoke of the glory of Everam. Their bellies were empty and their knees weak from exertion and lack of sleep, but the boys did not protest. The sight of Jardir, returned reeking and bloody from his punishment, had taught them all to obey without question.

Drillmaster Qeran struck Jardir hard with his strap. “Why do you suffer?” he demanded.

“Alagai!” Jardir shouted.

Qeran turned and whipped Abban. “Why is the Hannu Pash necessary?”

“Alagai!” Abban screamed.

“Without the alagai, all the world would be the paradise of Heaven, suffused in Everam’s embrace,” Dama Khevat said.

The drillmaster’s strap cracked on Jardir’s back again. Since his insolence the first day, he had taken two lashes for every one suffered by another boy.

“What is your purpose in this life?” Qeran cried.

“To kill alagai!” Jardir screamed.

His hand shot out, clutching Jardir around the throat and pulling him close. “And how will you die?” he asked quietly.

“On alagai talons,” Jardir choked. The drillmaster released him, and he gasped in a breath, standing back to attention before Qeran could find further reason to beat him.

“On alagai talons!” Khevat cried. “Dal’Sharum do not die old in their beds! They do not fall prey to sickness or hunger! Dal’Sharum die in battle, and win into paradise. Basking in Everam’s glory, they bathe and drink from rivers of sweet cool milk, and have virgins beyond count devoted to them.”

“Death to alagai!” the boys all screamed at once, pumping their fists. “Glory to Everam!”

After these sessions, they were given their bowls, and the gruel pot was set out. There was never enough for all, and more than one boy each day went hungry. The older and larger boys, led by Hasik, had established their pecking order and filled their bowls first, but even they took but one ladle each. To take more, or to spill gruel in a scuffle at the pot, was to invite the wrath of the ever-present drillmasters.

As the older boys ate, the youngest and weakest of nie’Sharum fought hard among themselves for a place in line. After his first night’s beating and the day in the pits, Jardir was in no shape to fight for days, but Abban had taken well to using his weight as a weapon, and always secured them a place, even if it was close to the back.

When the bowls were emptied, the training began.

There were obstacle courses to build endurance, and long sessions practicing the sharukin—groups of movements that made up the forms of sharusahk. They learned to march and move in step even at speed. With nothing in their bellies but the thin gruel, the boys became like speartips, thin and hard as the weapons they drilled with.

Sometimes the drillmasters sent groups of boys to ambush nie’Sharum in neighboring sharaji, beating them severely. Nowhere was safe, not even when sitting at the waste pits. Sometimes the older boys like Hasik and his friends would mount the defeated boys from other tribes from behind, thrusting into them as if they were women. It was a grave dishonor, and Jardir had been forced to kick more than one attacker between the legs to avoid such a fate for himself. A Majah boy managed to pull down Abban’s bido once, but Jardir kicked him in the face so hard blood spurted from his nose.

“At any moment, the Majah could attack to take a well,” Kaval told Jardir when they came to him after the assault, “or the Nanji come to carry off our women. We must be ready at every moment of every day to kill or be killed.”

“I hate this place,” Abban whined, close to tears, when the drillmaster left. “I cannot wait for the Waning, when I can go home to my mother and sisters, if only for the new moon.”

Jardir shook his head. “He’s right. Letting your guard down, even for a moment, invites death.” He clenched his fist. “That may have happened to my father, but it won’t happen to me.”

After the drillmasters completed their lessons each day, the older boys supervised repetition, and they were no less quick to punish than the dal’Sharum.

“Keep your knees bent as you pivot, rat,” Hasik growled as Jardir performed a complicated sharukin. He punctuated his advice by kicking behind Jardir’s knees, driving him into the dust.

“The son of piss cannot perform a simple pivot!” Hasik cried to the other boys, laughing. His s’s still came out with a whistle through the gap where Qeran had knocked out one of his teeth.

Jardir growled and launched himself at the older boy. He might have to obey the dama and dal’Sharum, but Hasik was only nie’Sharum, and he would accept no insult to his father from the likes of him.

But Hasik was also five years his senior, and soon to lose his bido. He was larger than Jardir by far, and had years of experience at the deadly art of the empty hand. He caught Jardir’s wrist, twisting and pulling the arm straight, then pivoted to bring his elbow down hard on the locked limb.

Jardir heard the snap and saw the bone jut free of his skin, but there was a long moment of dawning horror before the blast of pain hit him.

And he screamed.

Hasik’s hand snapped over Jardir’s mouth, cutting off his howls and pulling him close.

“The next time you come for me, son of piss, I will kill you,” he promised.

Abban ducked under Jardir’s good arm and half carried him to the dama’ting pavilion at the far end of the training grounds. The tent opened as they approached, as if they had been expected. A tall woman clad in white from head to toe held the flap open, only her hands and eyes visible. She gestured to a table inside, and Abban hurried to place Jardir there, beside a girl who was clad all in white like a dama’ting. But her face, young and beautiful, was uncovered.

Dama’ting did not speak to nie’Sharum.

Abban bowed deeply when Jardir was in place. The dama’ting nodded toward the flaps, and he practically fell over himself in his haste to exit. It was said the dama’ting could see the future, and knew a man’s death just by looking at him.

The woman glided over to Jardir, a blur of white to his pain-clouded eyes. He could not tell if she was young or old, beautiful or ugly, stern or kind. She seemed above such petty things, her devotion to Everam transcending all mortal concern.

The girl lifted a small stick wrapped many times in white cloth and placed it in Jardir’s mouth, gently pushing his jaw closed. Jardir understood, and bit down.

“Dal’Sharum embrace their pain,” the girl whispered as the dama’ting moved to a table to gather instruments.

There was a sharp sting as the dama’ting cleansed the wound, and a flare of agony as she wrenched his arm to set the bone. Jardir bit hard into the stick, and tried to do as the girl said, opening himself to the pain, though he did not fully understand. For a moment the pain seemed more than he could endure, but then, as if he were passing through a doorway, it became a distant thing, a suffering he was aware of but not part of. His jaw unclenched, and the stick fell away unneeded.

As Jardir relaxed into the pain, he turned to watch the dama’ting. She worked with calm efficiency, murmuring prayers to Everam as she stitched muscle and skin. She ground herbs into a paste she slathered on the wound, wrapping it in clean cloth soaked in a thick white mixture.

With surprising strength, she lifted him from the table and set him on a hard cot. She put a flask to his lips and Jardir drank, immediately feeling warm and woozy.

The dama’ting turned away, but the girl lingered a moment. “Bones become stronger after being broken,” she whispered, giving comfort as Jardir drifted off to sleep.

He woke to find the girl sitting beside his cot. She pressed a damp cloth to his forehead. It was the coolness that had woken him. His eyes danced over her uncovered face. He had once thought his mother beautiful, but it was nothing compared with this girl.

“The young warrior awakens,” she said, smiling at him.

“You speak,” Jardir said through parched lips. His arm seemed encased in white stone; the dama’ting’s wrappings had hardened while he slept.

“Am I a beast, that I should not?” the girl asked.

“To me, I mean,” Jardir said. “I am only nie’Sharum.” And not yet worthy of you by half, he added silently.

The girl nodded. “And I am nie’dama’ting. I will earn my veil soon, but I do not wear it yet, and thus may speak to whomever I wish.”

She set the cloth aside, lifting a steaming bowl of porridge to his lips. “I expect they are starving you in the Kaji’sharaj. Eat. It will help the dama’ting’s spells to heal you.”

Jardir swallowed the hot food quickly. “What is your name?” he asked when done.

The girl smiled as she wiped his mouth with a soft cloth. “Bold, for a boy barely old enough for his bido.”

“I’m sorry,” Jardir said.

She laughed. “Boldness is no cause for sorrow. Everam has no love for the timid. My name is Inevera.”

“As Everam wills,” Jardir translated. It was a common saying in Krasia. Inevera nodded.

“Ahmann,” Jardir introduced himself, “son of Hoshkamin.”

The girl nodded as if this were grave news, but there was amusement in her eyes.