Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

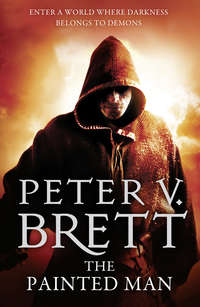

Kitabı oku: «The Painted Man», sayfa 3

âNo more gold,â he clarified, âbut surely Jenya could do with a cask of rice, or some cured fish or meal.â

âIndeed she could,â Ragen said.

âI can find work for your Jongleur, too,â Rusco added. âHeâll see more custom here in the Square than by hopping from farm to farm.â

âAgreed,â Ragen said. âKeerin will need gold, though.â

Rusco gave him a wry look, and Ragen laughed. âHad to try ⦠you understand!â he said. âSilver, then.â

Rusco nodded. âIâll charge a moon for every performance, and for every moon, Iâll keep one star and he the other three.â

âI thought you said the townies had no money,â Ragen noted.

âMost donât,â Rusco said. âIâll sell the moons to them ⦠say at the cost of five credits.â

âSo Rusco Hog skims from both sides of the deal?â Ragen asked.

Hog smiled.

Arlen was excited during the ride back. Old Hog had promised to let him see the Jongleur for free if he spread the word that Keerin would be entertaining in the Square at high sun the next day for five credits or a silver Milnese moon. He wouldnât have much time; his parents would be readying to leave just as he and Ragen returned, but he was sure he could spread the word before they pulled him onto the cart.

âTell me about the Free Cities,â Arlen begged as they rode. âHow many have you seen?â

âFive,â Ragen said, âMiln, Angiers, Lakton, Rizon, and Krasia. There may be others beyond the mountains or the desert, but none that I know have seen them.â

âWhat are they like?â Arlen asked.

âFort Angiers, the forest stronghold, lies south of Miln, across the Dividing River,â Ragen said. âAngiers supplies wood for the other cities. Farther south lies the great lake, and on its surface stands Lakton.â

âIs a lake like a pond?â Arlen asked.

âA lake is to a pond what a mountain is to a hill,â Ragen said, giving Arlen a moment to digest the thought. âOut on the water, the Laktonians are safe from flame, rock, and wood demons. Their wardnet is proof against wind demons, and no people can ward against water demons better. Theyâre fisher-folk, and thousands in the southern cities depend on their catch for food.

âWest of Lakton is Fort Rizon, which is not technically a fort, since you could practically step over its wall, but it shields the largest farmlands youâve ever seen. Without Rizon, the other Free Cities would starve.â

âAnd Krasia?â Arlen asked.

âI only visited Fort Krasia once,â Ragen said. âThe Krasians arenât welcoming to outsiders, and you need to cross weeks of desert to get there.â

âDesert?â

âSand,â Ragen explained. âNothing but sand for miles in every direction. No food nor water but what you carry, and nothing to shade you from the scorching sun.â

âAnd people live there?â Arlen asked.

âOh, yes,â Ragen said. âThe Krasians used to be even more numerous than the Milnese, but theyâre dying off.â

âWhy?â Arlen asked.

âBecause they fight the corelings,â Ragen said.

Arlenâs eyes widened. âYou can fight corelings?â he asked.

âYou can fight anything, Arlen,â Ragen said. âThe problem with fighting corelings is that more often than not, you lose. The Krasians kill their share, but the corelings give better than they get. There are fewer Krasians every year.â

âMy da says corelings eat your soul when they get you,â Arlen said.

âBah!â Ragen spat over the side of the cart. âSuperstitious nonsense.â

They had turned a bend not far from the Cluster when Arlen noticed something dangling from the tree ahead of them. âWhatâs that?â he asked, pointing.

âNight,â Ragen swore, and cracked the reins, sending the mollies into a gallop. Arlen was thrown back in his seat, and took a moment to right himself. When he did, he looked at the tree, which was coming up fast.

âUncle Cholie!â he cried, seeing the man kicking his feet as he clawed at the rope around his neck.

âHelp! Help!â Arlen screamed. He leapt from the moving cart, hitting the ground hard, but he bounced to his feet, darting towards Cholie. He got up under the man, but one of Cholieâs thrashing feet kicked him in the mouth, knocking him down. He tasted blood, but strangely there was no pain. He came up again, grabbing Cholieâs legs and trying to lift him up to loosen the rope, but he was too short, and Cholie too heavy besides, and the man continued to gag and jerk.

âHelp him!â Arlen cried to Ragen. âHeâs choking! Somebody help!â

He looked up to see Ragen pull a spear from the back of the cart. The Messenger drew back and threw with hardly a moment to aim, but his aim was true, severing the rope and collapsing poor Cholie onto Arlen. They both fell to the ground.

Ragen was there in an instant, pulling the rope from Cholieâs throat. It didnât seem to make much difference, the man still gagged and clawed at his throat. His eyes bulged so far it looked as if they would pop right out of his head, and his face was so red it looked purple. Arlen screamed as he gave a tremendous thrash, and then lay still.

Ragen beat Cholieâs chest and breathed huge gulps of air into him, but it had no effect. Eventually, the Messenger gave up, slumping in the dust and cursing.

Arlen was no stranger to death. That spectre was a frequent visitor to Tibbetâs Brook. But it was one thing to die from the corelings or from a chill. This was different.

âWhy?â he asked Ragen. âWhy would he fight so hard to survive last night, only to kill himself now?â

âDid he fight?â Ragen asked. âDid any of them really fight? Or did they run and hide?â

âI donât â¦â Arlen began.

âHiding isnât always enough, Arlen,â Ragen said. âSometimes, hiding kills something inside of you, so that even if you survive the demons, you donât really.â

âWhat else could he have done?â Arlen asked. âYou canât fight a demon.â

âIâd sooner fight a bear in its own cave,â Ragen said, âbut it can be done.â

âBut you said the Krasians were dying because of it,â Arlen protested.

âThey are,â Ragen said. âBut they follow their hearts. I know it sounds like madness, Arlen, but deep down, men want to fight, like they did in tales of old. They want to protect their women and children as men should. But they canât, because the great wards are lost, so they knot themselves like caged hares, hiding terrified through the night. But sometimes, especially when you see loved ones die, the tension breaks you and you just snap.â

He put a hand on Arlenâs shoulder. âIâm sorry you had to see this, boy,â he said. âI know it doesnât make a lot of sense right now â¦â

âNo,â Arlen said, âit does.â

And it was true, Arlen realized. He understood the need to fight. He had not expected to win when he attacked Cobie and his friends that day. If anything, he had expected to be beaten worse than ever. But in that instant when he grabbed the stick, he hadnât cared. He only knew he was tired of just taking their abuse, and wanted it to end, one way or another.

It was comforting to know he wasnât alone.

Arlen looked at his uncle, lying in the dust, his eyes wide with fear. He knelt and reached out, brushing his eyes closed with his fingertips. Cholie had nothing to fear any longer.

âHave you ever killed a coreling?â he asked the Messenger.

âNo,â Ragen said, shaking his head. âBut Iâve fought a few. Got the scars to prove it. But I was always more interested in getting away, or keeping them away from someone else, than I was in killing any.â

Arlen thought about that as they wrapped Cholie in a tarp and put him in the back of the wagon, hurrying back to the Cluster. Jeph and Silvy had already packed the cart and were waiting impatiently to leave, but the sight of the body defused their anger at Arlenâs late return.

Silvy wailed and threw herself on her brother, but there was no time to waste, if they were to make it back to the farm by nightfall. Jeph had to hold her back as Tender Harral painted a ward on the tarp and led a prayer as he tossed Cholie into the pyre.

The survivors who werenât staying in Brine Cutterâs house were divided up and taken home with the others. Jeph and Silvy had offered succour to two women. Norine Cutter was over fifty summers old. Her husband had died some years back, and she had lost her daughter and grandson in the attack. Marea Bales was old, too; almost forty. Her husband had been left outside when the others drew lots for the cellar. Like Silvy, both slumped in the back of Jephâs cart, staring at their knees. Arlen waved goodbye to Ragen as his father cracked the whip.

The Cluster by the Woods was drawing out of sight when Arlen realized he hadnât told anyone to come see the Jongleur.

2

If It Was You 319 AR

They had just enough time to stow the cart and check the wards before the corelings came. Silvy had little energy for cooking, so they ate a cold meal of bread, cheese, and sausage, chewing with little enthusiasm. The demons came soon after sunset to test the wards, and every time the magic flared to throw them back, Norine cried out. Marea never touched her food. She sat on her pallet with her arms wrapped tightly around her legs, rocking back and forth and whimpering whenever the magic flared. Silvy cleared the plates, but she never returned from the kitchen, and Arlen could hear her crying.

Arlen tried to go to her, but Jeph caught his arm. âCome talk with me, Arlen,â he said.

They went into the small room that housed Arlenâs pallet, his collection of smooth rocks from the brook, and all his feathers and bones. Jeph selected one of these, a brightly coloured feather about ten inches long, and fingered it as he spoke, not looking Arlen in the eye.

Arlen knew the signs. When his father wouldnât look at him, it meant he was uncomfortable with whatever he wanted to talk about.

âWhat you saw on the road with the Messengerââ Jeph began.

âRagen explained it to me,â Arlen said. âUncle Cholie was dead already, he just didnât know it right away. Sometimes people live through an attack, but die anyway.â

Jeph frowned. âNot how I would have put it,â he said. âBut true enough, I suppose. Cholie â¦â

âWas a coward,â Arlen finished.

Jeph looked at him in surprise. âWhat makes you say that?â he asked.

âHe hid in the cellar because he was scared to die, and then killed himself because he was scared to live,â Arlen said. âBetter if he had just picked up an axe and died fighting.â

âI donât want to hear that kind of talk,â Jeph said. âYou canât fight demons, Arlen. No one can. Thereâs nothing to be gained by getting yourself killed.â

Arlen shook his head. âTheyâre like bullies,â he said. âThey attack us because weâre too scared to fight back. I hit Cobie and the others with that stick, and they didnât bother me again.â

âCobie ent a rock demon,â Jeph said. âNo stick is going to scare those off.â

âThereâs got to be a way,â Arlen said. âPeople used to do it. All the old stories say so.â

âThe stories say there were magic wards to fight with,â Jeph said. âThe fighting wards are lost.â

âRagen says they still fight demons in some places. He says it can be done.â

âIâm going to have a talk with that Messenger,â Jeph grumbled. âHe shouldnât be filling your head with such thoughts.â

âWhy not?â Arlen said. âMaybe more people would have survived last night, if all the men had gotten axes and spears â¦â

âThey would be just as dead,â Jeph finished. âThereâs other ways to protect yourself and your family, Arlen. Wisdom. Prudence. Humility. Itâs not brave to fight a battle you canât win.

âWho would care for the women and the children if all the men got themselves cored trying to kill what canât be killed?â he went on. âWho would chop the wood and build the homes? Who would hunt and herd and plant and slaughter? Who would seed the women with children? If all the men die, the corelings win.â

âThe corelings are already winning,â Arlen muttered. âYou keep saying the town gets smaller each year. Bullies keep coming when you donât fight back.â

He looked up at his father. âDonât you feel it? Donât you want to fight sometimes?â

âOf course I do, Arlen,â Jeph said. âBut not for no reason. When it matters, when it really matters, all men are willing to fight. Animals run when they can, and fight when they must, and people are no different. But that spirit should only come out when needed.

âBut if it was you out there with the corelings,â he said, âor your mam, I swear I would fight like mad before I let them get near you. Do you understand the difference?â

Arlen nodded. âI think so.â

âGood man,â Jeph said, squeezing his shoulder.

Arlenâs dreams that night were filled with images of hills that touched the sky, and ponds so big you could put a whole town on the surface. He saw yellow sand stretching as far as his eyes could see, and a walled fortress hidden in the trees.

But he saw it all between a pair of legs that swayed lazily before his eyes. He looked up, and saw his own face turning purple in the noose.

He woke with a start, his pallet damp with sweat. It was still dark, but there was a faint lightening on the horizon, where the indigo sky held a touch of red. He lit a candle stub and pulled on his overalls, stumbling out to the common room. He found a crust to chew on as he took out the egg basket and milk jugs, putting them by the door.

âYouâre up early,â said a voice behind him. He turned, startled, to find Norine staring at him. Marea was still on her pallet, though she tossed in her sleep.

âThe days donât get any longer while you sleep,â Arlen said.

Norine nodded. âSo my husband used to say,â she agreed. ââBaleses and Cutters canât work by candlelight, like the Squares,â heâd say.â

âI have a lot to do,â Arlen said, peeking through the shutter to see how long he had before he could cross the wards. âThe Jongleur is supposed to perform at high sun.â

âOf course,â Norine agreed. âWhen I was your age, the Jongleur was the most important thing in the world to me, too. Iâll help you with your chores.â

âYou donât have to do that,â Arlen said. âDa says you should rest.â

Norine shook her head. âRest just makes me think of things best left unthought,â she said. âIf Iâm to stay with you, I should earn my keep. After chopping wood in the Cluster, how hard could it be to slop pigs and plant corn?â

Arlen shrugged, and handed her the egg basket.

With Norineâs help, the chores went by fast. She was a quick learner, and no stranger to hard work and heavy lifting. By the time the smell of eggs and bacon wafted from the house, the animals were all fed, the eggs collected, and the cows milked.

âStop squirming on the bench,â Silvy told Arlen as they ate.

âYoung Arlen canât wait to go see the Jongleur,â Norine advised.

âMaybe tomorrow,â Jeph said, and Arlenâs face fell.

âWhat!â Arlen cried. âButââ

âNo buts,â Jeph said. âA lot of work went undone yesterday, and I promised Selia Iâd drop by the Cluster in the afternoon to help out.â

Arlen pushed his plate away and stomped into his room.

âLet the boy go,â Norine said when he was gone. âMarea and I will help out here.â Marea looked up at the sound of her name, but went back to playing with her food a moment later.

âArlen had a hard day, yesterday,â Silvy said. She bit her lip. âWe all did. Let the Jongleur put a smile on his face. Surely thereâs nothing that canât wait.â

Jeph nodded after a moment. âArlen!â he called. When the boy showed his sullen face, he asked, âHow much is old Hog charging to see the Jongleur?â

âNothing,â Arlen said quickly, not wanting to give his father reason to refuse. âOn account of how I helped carry stuff from the Messengerâs cart.â It wasnât exactly true, and there was a good chance Hog would be angry that he forgot to tell people, but maybe if he spread word on the walk over, he could bring enough people for his two credits at the store to get him in.

âOld Hog always acts generous right after the Messenger comes,â Norine said.

âOught to, after how heâs been fleecing us all winter,â Silvy replied.

âAll right, Arlen, you can go,â Jeph said. âMeet me in the Cluster afterwards.â

The walk to Town Square took about two hours if you followed the path. Nothing more than a wagon track of hard-packed soil that Jeph and a few other locals kept clear, it went well out of the way to the bridge at the shallowest part of the brook. Nimble and quick, Arlen could cut the trip in half by skipping across the slick rocks jutting from the water.

Today, he needed the extra time more than ever, so he could make stops along the way. He raced along the muddy bank at breakneck speed, dodging treacherous roots and scrub with the sure-footed confidence of one who had followed the trail countless times.

He popped back out of the woods as he passed the farmhouses on the way, but there was no one to be found. Everyone was either out in the fields or back at the Cluster helping out.

It was getting close to high sun when he reached Fishing Hole. A few of the Fishers had their boats out on the small pond, but Arlen didnât see much point in shouting to them. Otherwise, the Hole was deserted, too.

He was feeling glum by the time he got to Town Square. Hog might have seemed nicer than usual yesterday, but Arlen had seen what he was like when someone cost him profit. There was no way he was going to let Arlen see the Jongleur for just two credits. Heâd be lucky if the storekeep didnât take a switch to him.

But when he reached the square, he found over three hundred people gathered from all over the Brook. There were Fishers and Marshes and Boggins and Bales. Not to mention the town locals, Squares, Tailors, Millers, Bakers, and all. None had come from Southwatch, of course. Folk there shunned Jongleurs.

âArlen, my boy!â Hog called, seeing him approach. âIâve saved you a spot up front, and youâll go home tonight with a sack of salt! Well done!â

Arlen looked at him curiously, until he saw Ragen, standing next to Hog. The Messenger winked at him.

âThank you,â Arlen said, when Hog went off to mark another arrival in his ledger. Dasy and Catrin were selling food and ale for the show.

âPeople deserve a show,â Ragen said with a shrug. âBut not without clearing it with your Tender, it seems.â He pointed to Keerin, who was deep in conversation with Tender Harral.

âDonât be selling any of that Plague nonsense to my flock!â Harral said, poking Keerin hard in the chest. He was twice the Jongleurâs weight, and none of it fat.

âNonsense?â Keerin asked, paling. âIn Miln, the Tenders will string up any Jongleur that doesnât tell of the Plague!â

âI donât care what they do in the Free Cities,â Harral said. âTheseâre good people, and they have it hard enough without you telling âem their sufferingâs because they ent pious enough!â

âWhat â¦?â Arlen began, but Keerin broke off, heading to the centre of the square.

âBest find a seat quick,â Ragen advised.

As Hog promised, Arlen got a seat right in front, in the area usually left for the younger children. The others looked on enviously, and Arlen felt very special. It was rare for anyone to envy him.

The Jongleur was tall, like all Milnese, dressed in a patchwork of bright colours that looked like they were stolen from the dyerâs scrap bin. He had a wispy goatee, the same carrot-colour as his hair, but the moustache never quite met the beard, and the whole thing looked like it might wash off with a good scrubbing. Everyone, especially the women, talked in wonder about his bright hair and green eyes.

As people continued to file in, Keerin paced back and forth, juggling his coloured wooden balls and telling jokes, warming to the crowd. When Hog gave the signal, he took his lute and began to play, singing in a strong, high voice. People clapped along to the songs they didnât know, but whenever he played one that was sung in the Brook, the whole crowd sang along, drowning out the Jongleur and not seeming to care. Arlen didnât mind; he was singing just as loud as the others.

After the music came acrobatics, and magic tricks. Along the way, Keerin made a few jests about husbands that had the women shrieking with laughter while the men frowned, and a few about wives that had the men slapping their thighs as the women glared.

Finally, the Jongleur paused and held up his hands for silence. There was a murmur from the crowd, and parents nudged their youngest children forward, wanting them to hear. Little Jessi Boggin, who was only five, climbed right into Arlenâs lap for a better view. Arlen had given her family a few pups from one of Jephâs dogs a few weeks ago, and now she clung to him whenever he was near. He held her as Keerin began the Tale of the Return, his high voice dropping into a deep, booming call that carried far into the crowd.

âThe world was not always as you see it,â the Jongleur told the children. âOh no. There was a time when humanity lived in balance with the demons. Those early years are called the Age of Ignorance. Does anyone know why?â He looked around the children in front, and several raised their hands.

âBecause there wasnât any wards?â a girl asked, when Keerin pointed to her.

âThatâs right!â the Jongleur said, turning a somersault that brought squeals of glee from the children. âThe Age of Ignorance was a scary time for us, but there werenât as many demons then, and they couldnât kill everyone. Much like today, humans built what they could during the day, and the demons would tear it down each night.

âAs we struggled to survive,â Keerin went on, âwe adapted, learning how to hide food and animals from the demons, and how to avoid them.â He looked around as if in terror, and then ran behind one child, cringing. âWe lived in holes in the ground, so they couldnât find us.â

âLike bunnies?â Jessi asked, laughing.

âJust so!â Keerin called, putting a twitching finger up behind each ear and hopping about, wriggling his nose.

âWe lived any way we could,â he went on, âuntil we discovered writing. From there, it wasnât long before we had learned that some writing could hold the corelings back. What writing is that?â he asked, cupping an ear.

âWards!â everyone cried in unison.

âCorrect!â the Jongleur congratulated with a flip. âWith wards, we could protect ourselves from the corelings, and we practised them, getting better and better. More and more wards were discovered, until someone learned one that did more than hold the demons back. It hurt them.â The children gasped, and Arlen, even though he had heard almost this same performance every year for as long as he could remember, found himself sucking in his breath. What he wouldnât give to know such a ward!

âThe demons did not take well to this advancement,â Keerin said with a grin. âThey were used to us running and hiding, and when we turned and fought, they fought back. Hard. Thus began the First Demon War, and the second age, the Age of the Deliverer.

âThe Deliverer was a man called upon by the Creator to lead our armies, and with him to lead us, we were winning!â He thrust his fist into the air and the children cheered. It was infectious, and Arlen tickled Jessi with glee.

âAs our magics and tactics improved,â Keerin said, âhumans began to live longer, and our numbers swelled. Our armies grew larger, even as the number of demons dwindled. There was hope that the corelings would be vanquished once and for all.â

The Jongleur paused then, and his face took on a serious expression. âThen,â he said, âwithout warning, the demons stopped coming. Never in the history of the world had a night passed without the corelings. Now night after night went by with no sign of them, and we were baffled.â He scratched his head in mock confusion. âMany believed that the demon losses in the war had been too great, and that they had given up the fight, cowering with fright in the Core.â He huddled away from the children, hissing like a cat and shaking as if with fear. Some of the children got into the act, growling at him menacingly.

âThe Deliverer,â Keerin said, âwho had seen the demons fight fearlessly every night, doubted this, but as months passed without sign of the creatures, his armies began to fragment.

âHumanity rejoiced in their victory over the corelings for years,â Keerin went on. He picked up his lute and played a lively tune, dancing about, but then the tune turned ominous, and the Jongleurâs voice deepened once more. âBut as the years passed without the common foe, the brotherhood of men grew strained, and then faded. For the first time, we fought against one another. As war sparked, the Deliverer was called upon by all sides to lead, but he shouted, âIâll not fight âgainst men while a single demon remains in the Core!â He turned his back, and left the lands as armies marched and all the land fell into chaos.

âFrom these great wars arose powerful nations,â he said, turning the tune into something uplifting, âand mankind spread far and wide, covering the entire world. The Age of the Deliverer came to a close, and the Age of Science began.

âThe Age of Science,â the Jongleur said, âwas our greatest time, but nestled in that greatness was our biggest mistake. Can any here tell me what it was?â The older children knew, but Keerin signalled them to hold back and let the young ones answer.

âBecause we forgot magic,â Gim Cutter said, wiping his nose with the back of his hand.

âRight you are!â Keerin said, snapping his fingers. âWe learned a great deal about how the world worked, about medicine and machines, but we forgot magic, and worse, we forgot the corelings. After three thousand years, no one believed they had ever even existed.

âWhich is why,â he said grimly, âwe were unprepared when they came back.

âThe demons had multiplied over the centuries, as the world forgot them. Then, three hundred years ago, they rose from the Core one night in massive numbers to take it back.

âWhole cities were destroyed that first night, as the corelings celebrated their return. Men fought back, but even the great weapons of the Age of Science were poor defence against the demons. The Age of Science came to a close, and the Age of Destruction took hold.

âThe Second Demon War had begun.â

In his mindâs eye, Arlen saw that night, saw the cities burning as people fled in terror, only to be savaged by the waiting corelings. He saw men sacrifice themselves to buy time for their families to flee, saw women take claws meant for their children. Most of all, he saw the corelings dance, cavorting in savage glee as blood ran from their teeth and talons.

Keerin moved forward even as the children drew back in fear. âThe war lasted for years, with people slaughtered at every turn. Without the Deliverer to lead them, they were no match for the corelings. Overnight, the great nations fell, and the accumulated knowledge of the Age of Science burned as flame demons frolicked.

âScholars desperately searched the wreckages of libraries for answers. The old science was no help, but they found salvation at last in stories once considered fantasy and superstition. Men began to draw clumsy symbols in the soil, preventing the corelings from approaching. The ancient wards held power still, but the shaking hands that drew them often made mistakes, and they were paid for dearly.

âThose who survived gathered people to them, protecting them through the long nights. Those men became the first Warders, who protect us to this very day.â The Jongleur pointed to the crowd, âSo the next time you see a Warder, thank him, because you owe him your life.â

That was a variation on the story Arlen had never heard Warders? In Tibbetâs Brook, everyone learned warding as soon as they were old enough to draw with a stick. Many had poor aptitude for it, but Arlen couldnât imagine anyone not taking the time to learn the basic forbiddings against flame, rock, swamp, water, wind, and wood demons.

âSo now we stay safe within our wards,â Keerin said, âletting the demons have their pleasures outside. Messengers,â he gestured to Ragen, âthe bravest of all men, travel from city to city for us, bringing news and escorting men and goods.â

He walked about, his eyes hard as he met the frightened looks of the children. âBut we are strong,â he said. âArenât we?â

The children nodded, but their eyes were still wide with fear.

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.