Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

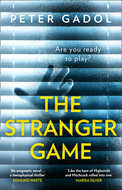

Kitabı oku: «The Stranger Game»

Praise for The Stranger Game

‘An enigmatic novel … a metaphysical thriller’

Edmund White

‘Like the best of Highsmith and Hitchcock rolled into one’

Marisa Silver

‘Beautiful, thoughtful meditation on the invisible ties that bind us-even to strangers’

Kirkus Reviews

‘Engrossing…. Those with a taste for the offbeat will find this well worth reading’

Publishers Weekly

‘A phenomenal mystery novel filled with action and a story line that makes you think about human interaction’

The Oklahoman

‘This is Patricia Highsmith-style suspense, edgy and a little dreamy, with a sense of uncertainty lurking everywhere’

Booklist

‘A fun, moody, twisty thriller, with a sun-touched, West Coast vibe…as much Joan Didion as Patricia Highsmith’

Scott Smith

‘“Following” gets a whole new meaning in Peter Gadol’s stylish psychological thriller’

Janet Fitch

PETER GADOL is the author of seven novels including The Stranger Game, Silver Lake, Light at Dusk, and The Long Rain. His work his been translated for foreign editions and appeared in literary journals, including StoryQuarterly, the Los Angeles Review of Books Quarterly Journal, and Tin House. Gadol lives in Los Angeles, where he is Chair and Professor of the MFA Writing program at Otis College of Art and Design.

Also by Peter Gadol

Coyote

The Mystery Roast

Closer to the Sun

The Long Rain

Light at Dusk

Silver Lake

The Stranger Game

Peter Gadol

ONE PLACE. MANY STORIES

Copyright

An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by HQ in 2019

Copyright © Peter Gadol 2019

Peter Gadol asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Ebook Edition © September 2019 ISBN: 978-1-474-09297-5

Note to Readers

This ebook contains the following accessibility features which, if supported by your device, can be accessed via your ereader/accessibility settings:

Change of font size and line height

Change of background and font colours

Change of font

Change justification

Text to speech

Page numbers taken from the following print edition: ISBN 9781848457690

For Chris

Somehow never strangers

Contents

Cover

PRAISE

About the Author

Booklist

Title Page

COPYRIGHT

NOTE TO READERS

Dedication

Part 1

Part 2

Part 3

Part 4

Part 5

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

1

THE FIRST TIME I FOLLOWED ANYONE WAS ON A SUNDAY afternoon in late November, the sky still gray with ash some weeks after a wildfire to the north. I had gone out on a hike, hoping to clear my mind by scrambling up the narrow path of a dry canyon, which worked until I walked the down trail back to my car. As I was driving out of the park, I passed a picnic area where there was a party underway, a birthday celebration with a hacked-at piñata twirling off a low branch, smoke rising from blackened grills, balloons tethered to the benches. At the periphery, I noticed a little boy, himself a balloon in a red, round jacket and red, round pants. He didn’t seem to be the center of attention, so I didn’t think he was the birthday boy. He must have been about three. He was tossing an inflated ball, also red, back and forth to his parents, or not exactly to his parents. He launched the ball instead toward the road where I’d pulled over and parked. I hadn’t planned any of this, but then that was how the game was played, how it began, the first rule: choose your subjects at random.

The balloon boy picked up the ball and tried throwing it again, but he couldn’t seem to get it to either parent; it kept falling short. Why didn’t they stand closer? Why were they making it difficult for him, was this some kind of test? The boy began flapping his arms, exasperated, until mercifully his mother pulled him aside for a hot dog. The boy’s father accepted a beer from another man. Trying to persuade the boy to eat was apparently the wrong move because he shook his head from side to side, cranky right when the afternoon sun both cracked the clouds and began to fade.

The boy’s mother scooped him up in her arms, although it looked like he was getting heavy for her, and carried him to a bright green box of a car parked three spaces in front of mine. Did she notice me? No, why would she? There was nothing so peculiar about a fortyyear-old woman sitting alone in a gray car idling in a city park. Although that afternoon I was full of longing, and who really knew what I was capable of doing.

The mother fit her boy into a car seat, strapped him in, and brushed his hair off his face. The boy’s father had followed them to the car but didn’t get in. The woman turned toward him to give him a quick, meaningful kiss, and I heard the man shout as he walked away that he’d call her later when he got home, which elicited an easy smile from the woman.

I revised my story. She was a single mother, right now only dating this man; she’d brought her son to a party the man had said the boy might enjoy. The woman and the man had been seeing each other for six months, and he was the first guy in a long while who she felt was good with her son, better than the boy’s actual father. I should have been rooting for them, for their happiness, but I wondered: If the woman and man wound up together permanently, would he be one of those guys who believed their marriage wouldn’t be complete until she gave him a child of his own? How would the woman’s son handle it? Would the challenge of a new sibling prepare him for all of the other uncertainties ahead, his body changing, the girls or the boys he’d want to take to his own picnics, the inevitable dramas of his own making? Would he continue wearing red jackets with red pants? Would he come into his body as an athlete, or would he excel at piano or math or debate, or all of the above—no, something else, but what?

These were the questions I was asking while trailing the green car out of the park and east along the boulevard, then south, skirting downtown. Traffic gave me cover, but it also meant I had to drive aggressively if I didn’t want to lose them. There was an unexpected pleasure in trying to remain unobserved while in pursuit.

Twenty minutes later, we ended up on the east side of the river heading into a part of the city I didn’t know well, and as traffic thinned, it had to be obvious I was behind them. Did the woman see me in her mirror? Did she call her boyfriend and chatter for the sake of it, keeping him on the line in case she needed to tell him a woman wearing dark glasses was following her home?

We were coasting through a newer development, the streets as flat as their map. When the woman turned into a driveway, I continued on and pulled over at the end of the block, five houses away. Now I watched them in my side-view mirror: the woman helped the boy out of the back seat, and she was trying to gather their things and order him into the house, but he was having none of it, sprinting across the yard toward its one leafless tree. Then the boy tripped. He fell first on his knees, then his palms. He wailed.

The woman jogged over and knelt down next to him, righting him, shaking her head, neither angry nor concerned. It wasn’t a bad fall. She reached her arms around him and once again she brushed his bangs across his forehead. The boy probably had learned that the longer he wept, the longer his mother would hold him, and so he kept crying. His mother rocked him—and was she smiling? How long would she be able to comfort him like this, her silly boy? I wondered what it was like to be needed in this way, and to know it was a fleeting dependence. The autumn sky turned amber with the last trace of light.

Suddenly from the open back door of the woman’s car, the red ball fell out. It rolled all the way down the driveway to the street. Neither the woman nor her son appeared to notice. The breeze carried the ball down the grade toward where I was parked. My first instinct was to hop out and retrieve it and bring it back to the boy, but then I would have revealed my position and possibly alarmed the woman if she put together how far I’d followed her. Also I would have broken the second rule of the game: no contact.

The red ball continued to roll down the middle of the street, pushed on by the evening wind. Would the boy ever find it? Would his mother notice it missing? Was it lost for good? I would never know. I would never see them again. The third rule of the game was never follow the same stranger twice, and so I drove away.

I PREFERRED TO BE IN MY SMALL TIDY HOUSE AT NIGHT rather than during the day because after dark I was less apt to notice whatever I might have been neglecting, the settlement cracks along the ceiling edge or the chipped bathroom tile. No matter the hour though, there was no avoiding the long wardrobe closet I could never fill on my own or the open corner of the main room once occupied by a plain birch writing desk. Then there was the garden all around the lot that existed in a state of permanent disgrace. My ex-boyfriend had been the one who tended to the knotty fall of chaparral down the back slope, although when Ezra moved out, he promised he would come by and take care of this plus the dozen succulents he’d potted during a period of unemployment; he did at first, but then stopped. I noted in my datebook to drench everything every five days. I’d probably overwatered the poor things until they gave up on me. I’d never wanted to own a house by myself, let alone tend its garden. That wasn’t the plan. I’d bought the house with marriage in mind. Here was the kitchen where we improvised spice blends, our mortar and pestle verdantly stained; here was the couch where we read aloud to each other the thrillers neither one of us read on our own; here was our bed, our weekend-morning island exile.

I was in a strange mood when I got back from following the woman and her son. I took a bottle of wine out back. High up on the hillside looking west, the city lights looked like an unstrung necklace, the basin covered with bright scattered beads. I kept picturing the way the little boy leaned into his mother, crying, comforted. I thought of myself as someone who would have the capacity to be a good parent to a happy-go-lucky kid, and there was a time when Ezra and I talked about getting pregnant or more likely adoption. Adoption wasn’t something I saw myself doing alone; friends did it solo, admirably and well, but that wasn’t for me.

I drank the wine fast and poured myself another glass. As I understood it, playing the stranger game was supposed to help you connect (or reconnect) in the most essential way with your fellow beings on the planet, help you renew your sense of empathy, yet I was only left lonelier that night. We were living in dark times, season after season of political uncertainty and social unrest; solitude only amplified my anxiety about the future. Ezra used to have a way of calming me down, and when I was with him (and when he was in one of his loftier moods), I believed progress was still possible, that together we (he and I, all of us) would prevail against the forces that would undo what we believed in. But Ezra was gone. He’d disappeared two months earlier. I missed him even more than I did after the final time we broke up.

A brief history: We had been friendly in college and shared meals but never dated. We took an art history survey together and then another course on modern movements, and I probably resented the way everything came to him so effortlessly, good grades, girls smarter than him. I didn’t take him seriously. Two summers after graduation we re-met at a rooftop party. I was in graduate school and Ezra was copyediting at a magazine. We stood off in a corner and made up stories about the guests we didn’t know. And we always did that, I have to say, long before it became part of any faddish game, which was hardly original, which was something people have always done while loitering in cafés and airport lounges or riding trains. Ezra and I were the same height, both short, which made whispering in each other’s ears easy. Right away I knew I’d always crave his breath against my neck. Unlike the men I’d been with before, he didn’t become some other animal when we made love later that night. He was playful, open, but also it was clear he had his secrets, fish sleeping beneath the surface of a frozen lake. Unlike the men I’d been with before, he wasn’t so easy to figure out, and I will admit that was what initially drew me to him.

We started taking road trips up the coast. We were curious about the same things, figurative painting, slow-cooked food, small towns far from other small towns. And yet we were also very different people. Ezra often wanted to be alone; I never did. His long black hair had a way of hiding half his glance; I usually pulled mine back into a ponytail. When he didn’t shave for a week, it seemed like he was hiding something. I’m grasping for some way to describe what I later understood better from a distance, and I’m dwelling too much on his appearance, although I was very attracted to him and wanted nothing more than to be close to him. His weeklong scruff was soft to touch.

That first morning after the rooftop party, we lay in bed with the blankets thrown back because the radiator was too aggressive. We had nowhere to be. We had all the time in the world for each other. When I was growing up, my father with his aches and pains often told me to enjoy my good health while it lasted and not take it for granted, but maybe the thing we really take for granted in our youth is time: back then an hour lasted longer, each day was epic.

We dated for a couple years and talked about moving in together but never did. Then there was a problem with my lease, I was going to have to move, and I pushed the subject, but Ezra said us sharing an apartment would never work. Never? I asked. As in never ever? My degree was in architecture, and all the way across the country there was a position at a firm that specialized in transforming old factories and warehouses into magnet schools and cultural centers, exactly the kind of work I most wanted to do. When I told Ezra about the job, he said I should go for it if I really wanted to, but he wouldn’t follow me out. His declaration came without elaboration and astonished me. We had a bitter fight; he accused me of plotting a course for myself while assuming he’d just fall in, independent Ezra who was sensitive about not getting anywhere in a career of his own. I think I was hurt to the extent I was because his accusation rang true. I applied for the job and got it.

After I moved, Ezra and I stayed in touch; we talked every couple of weeks, and one day my phone trilled with a text. Ezra had come west. He was near my office; in fact, he was at the museum down the street. More specifically, he was in the room with Madame B in Her Library, which he knew was my favorite painting, a tall early-modern portrait of a woman confined in a black buttoned-up gown yet grinning at the viewer with conspiratorial bemusement. The library was apparently invisible; the woman was painted against a brown backdrop with no books in sight. I didn’t believe Ezra was there. He texted back that there was only one way to find out.

He didn’t let go when he hugged me. His narrow shoulders, his veiny arms. His soft beard.

“Oh, Rebecca,” he said. “The biggest mistake of my thirty years was not following you out here.”

“We’re only twenty-eight,” I said.

“Whatever. I’m here now.”

“What makes you think I’d want you back?” I asked. “How do you know I’m not seeing someone?”

“You’re not.”

“You don’t know that. I don’t tell you everything.”

“You’re not,” he said again. “You can’t be.”

His breath warming my neck.

We lived together for eight years, at some point moving in to the house on the hill, using money my grandmother left me for a down payment. Those first two or three years in that house were the happiest of my life, a paradise to which I would struggle to return. Our last two years together, we argued frequently. I’d left my original job to form a studio with three partners, and we became busy entering every competition we could. We often worked late and through the weekend. Meanwhile Ezra wasn’t busy at all; he was always home waiting for me.

I kept up a stupid prolonged flirtation with one of my partners, who was married, which I am pretty sure Ezra never knew about while it was happening. My partner and I never had an actual tryst, and things cooled off, but my infatuation distracted me. The last year with Ezra was terrible. He kept saying he didn’t have a place in my life; he was a visitor. I’d tell him he was my life, but that sounded thin. I don’t have a place in my own life, he’d say, I’m a visitor there, too. I’d say that I didn’t know how to respond to that (or what he meant), and he’d snap: Why do you think you have to say anything? Some version of this conversation kept recurring. Then he’d say, I never wanted this house, it’s too much. I never wanted this garden, he’d say, or this view, and I’d say, You know that’s not true. You’re the one who always looked at the listings first. We weren’t making love. First tenderness left, then joy. When I got to my studio in the morning, I’d stretch out on a couch for a half hour with my eyes closed until I felt a yoke loosen across my shoulders. We agreed to try living apart for a time, although we knew this was less a trial than a prelude to our dissolution.

Ezra moved in to a small apartment up by the park and wanted to be free to see other people. He’d always been very sexual. I didn’t want to know about any of it, but eventually he told me when he came round to take care of the plants, and I didn’t interrupt him. The years fell away quickly, and we saw each other often; we were never out of each other’s lives. In many ways we grew closer again, confiding in each other once more, or, that is to say, he told me about the women he saw, none very seriously; I tended to tell him about my clients and projects. Ezra didn’t earn much as the assistant manager of the local bookstore, so I helped him out occasionally when he let me. He traveled with me to both of my parents’ funerals nine months apart. We met for dinner regularly, a movie sometimes. I cooked for him, he cooked for me. But I didn’t take him to dinner parties or events as my plus-one; he didn’t spend time with my friends. When we met up, it was always only the two of us. I never felt as centered as I did when I was driving back to the house on the hill after being in his company.

Whenever Ezra was involved with someone, we saw each other less. During these periods, I missed him but wanted him to settle down with someone new in a meaningful way. Only then would I be able to pursue my own happiness, then it would be my time; I can see now this was my thinking. The longest I’d ever gone without hearing from him was two weeks.

Two months ago in September, I hadn’t heard from Ezra for three weeks. I was busier than usual working on the conversion of a landmark insurance headquarters into a charter school. Something had happened between us—I won’t go into it—and I was trying to achieve some distance. When Ezra didn’t answer a series of texts, I thought, Well, I hope I like her.

Another week went by, and he still wasn’t answering my texts or calls, and I became worried. I dropped by his apartment. When I was knocking on his door, the property manager stepped out and said she assumed Ezra had gone away because he had missed his rent. This was very unusual. Weirdly though his car was still in his garage—she’d checked that morning. Ezra had known some dark days, and I didn’t think his depression ever became so unbearable that he’d harm himself, but I panicked. I had my key out before the property manager grabbed hers.

The wool blanket I’d given him for his last birthday was neatly folded across his made bed. Pillars of art books doubled as night tables. Ezra’s clothes, shoes, and luggage were in his closet. He had always been neat. The dishes were put away, but there were some salad greens going bad in the refrigerator. There was a stack of bills and magazines on his writing desk along with a fat biography of a poet bisected by a bookmark and a mug marked by rings of evaporated coffee. And next to the mug and the book was a printout of an article: it was the essay that had launched the stranger game.

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.