Kitabı oku: «Birds of Prey», sayfa 2

1 Adolf Galland, ‘Oberst Galland’, Wild und Hund, No. 47, 1941–42, pp. 357–358.

2 See Chris Bellamy, Absolute War: Soviet Russia in the Second World War, (London, 2007) and Evan Mawdsley, Thunder in the East: The Nazi-Soviet War 1941–1945, (London, 2016).

3 Helmut Heiber, David M. Glantz (ed), Hitler and his Generals: Military Conferences 1942–1945, (New York, 2002) pp. 14–17.

4 NARA, T175/140/2668141-355, Weisung Nr. 46: Richtlinien für die verstärkte Bekämpfung des Bandenunwesens im Osten, Der Führer, OKW/WFSt/Op. Nr. 002821/42g.K., Führerhauptquartier, 18 August 1942.

5 Philip W. Blood, Hitler’s Bandit Hunters: The SS and the Nazi Occupation of Europe, (Virginia, 2006), pp. 3–28.

6 TsAMO 500-12454-623, Bericht über die Bandenbekämpfung durch Einheiten der Luftwaffe im Bereich des Lw.Kdo.Ost von 10.4. bis 31.12.42, 8 Jan. 1943.

7 S.A. Kovpak, Our Partisan Course, (London, 1947). Stalin’s directive, 1 May 1942, instructed the bands to cause sabotage and destruction behind German lines.

8 TsAMO 500-12454-623, Bericht über die Bandenbekämpfung.

9 James Corum, “Die Luftwaffe und Kriegsverbrechen im Zweiten Weltkrieg.” in Gerd Überschär, Wolfram Wette (Hrs), Kriegsverbrechen im 20. Jahrhundert, (Festschrift für Manfred Messerschmidt), (Potsdam, 2001), p. 298.

10 TsAMO 500-623, Bericht über die Bandenbekämpfung.

Excursions in Microhistory

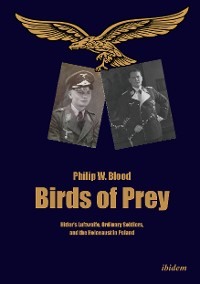

Writing history has history. The Luftwaffe’s participation in the Holocaust had always been on the fringe of history. Although Hitler’s air force was known to have held an instrumental part in the war, it was not associated with killing Jews, civilians, and partisans. The senior officers of the Luftwaffe tried to destroy the evidence in 1945 and very nearly succeeded. A small section of files survived that served as a catalyst for in-depth research of the Luftwaffe. The central thread of the narrative of this book is about ordinary Luftwaffe soldiers, the Landser and the Holocaust. The Landser is a slang word for the common soldier akin to the British Tommy. There was only partial evidence of the Landser’s footprint in the military documents. Consequently, painstaking research was adopted to piece together and collect scraps of evidence to construct a microhistory. From its origins in my PhD research, Birds of Prey was destined to be a microhistory. The research for this book, however, took a scientific path and applied historical GIS methods as forensic means to map the movements and the spatiality of the Landser. The outcome is this microhistory of Luftwaffe security troops in occupied Poland during the period 1942–44.

The general hypothesis underpinning this book re-confirmed my original research conclusions. Hitler’s Bandenbekämpfung was not conventional anti-partisan warfare or counterinsurgency. Bandenbekämpfung was not a bureaucratic reclassification of anti-partisan warfare without consequences, and the Wehrmacht was no longer able to conduct security operations within the parameters of its traditional guidelines. The application of Bandenbekämpfung was relatively easy and ideologically inexpensive. In practice, it vilified opponents, placed civilians under suspicion, and rendered them defenceless to exemplary punishment. Within its historiography, the school of military history has perpetuated the myth of Partisanenbekämpfung or anti-partisan warfare rather than recognise Bandenbekämpfung and its genocidal implications. This approach downplayed the place of Nazi ideology, as it sought to make sense of anti-partisan warfare. Given the evidence, this is no longer a sustainable argument. Bandenbekämpfung evolved from the forester’s battles with poachers and bandits. Christopher Hale makes a compelling argument that Bandenbekämpfung originated in the Thirty Years’ War. The word existed long before it was institionalised as a doctrine of militarised security in the Nineteenth Century. Bandenbekämpfung was radicalised as an operational doctrine within Imperial Germany’s colonizing security warfare, and was extended into the German way of war from 1908. Bandenbekämpfung was Germany’s approach to security warfare from 1942 onwards.1

The setting for the book’s research was Białowieźa forest in eastern Poland. This primaeval forest lies in the historical region of Podlasie and is famous as a habitat for the European bison. Białowieźa established a reputation for hunting and since the 1500s was a hunting reserve for the Polish kings. The forest and surrounding areas became populated with Poles, Lithuanians, Belorussians and Jews. There were few municipal conurbations, other than Bialystok, but many small towns, villages, and shtetls. The forest had a long history of authoritarian and violent occupation. After 1795, following the third partition of Poland, Białowieźa was subject to consecutive annexations: Prussia, Russia, Imperial Germany and then Nazi Germany in 1941. After 1918 this region once again returned to Poland, but war with Soviet Russia turned the region into one of the shattered lands of the east. After the experience of German Army occupation, during Great War, the Nazis increasingly craved the forest as a trophy. Hermann Göring pursued Hitler’s ambitions for Grossdeutschland (Greater German Reich) on the eastern frontier by locking Białowieźa forest into a defensive plan. This defensive plan envisaged a primaeval wilderness as a natural barrier to the threat of the ‘Bolshevik’ horde. In theory, this geopolitical strategy was scientifically sophisticated, but proved wholly naive as a defence line. This was Germany’s Maginot Line on the eastern frontier.

The research set out to explore how other ranks (ORs), or the rank and file, adapted to Bandenbekämpfung in Hitler’s race war. From 1942, the common soldiery perpetrated genocide in most theatres of the war: without overt ideological indoctrination; without being ordered by junior officers to commit crimes; and with everyday killing normalised to within military procedures or routines. There was no evidence the troops resisted this work. Indeed, trained into aggressive military concepts such as Auftragstaktik (mission-tactics) the soldiers were roused to heightened levels of violence.2 The research synthesized Göring’s geopolitical ambitions with the study of the Landser as perpetrators of genocide. In many ways this contradicted the general opinion that Göring disappeared into the shadows after Stalingrad. However, the findings set him apart from Hitler and Himmler. Whereas Hitler wanted to be excluded from the killing process, Himmler was a keen visitor to the extermination sites. Göring, in contrast, participated in the planning and willed its execution, but never visited the killing sites, or Białowieźa after the Nazi-occupation in June 1941.

My research focused upon Göring’s manipulation of two key institutions within his mandate as a Nazi leader. The German hunting fraternity and the Luftwaffe. Both institutions contained influential social elites and controlled a large proportion of the population. The hunt created the Nazified honour code for his ‘court etiquette’, and the Luftwaffe was the foundation of a ‘revolutionary’ military order. Together they merged the nstitutional symbolism of ‘The Blue’ (Luftwaffe) and ‘The Green’ (state forester-hunters). This was the culmination of Göring’s corporatism. By exploiting this institutional dynamic, Göring set about his plans for a permanent national frontier in the east. Stalin was determined to frustrate these plans and waged an intense insurgency campaign within Białowieźa. Göring escalated the conflict by sending Luftwaffe security troops to destroy the Soviet partisans. Jews fleeing to the forests to escape the Holocaust were caught in the middle and became victims of Göring’s hunter killers—the Landser. This microhistory was demarcated by three groups: Göring and the Nazi leaders plotting from the hunting lodges in East Prussia, the Luftwaffe soldiers on the ground hunting partisans and Jews, and the German hunt officials serving as the authoritarian lynchpin in the middle. Together, they all worked towards winning Hitler’s race war, but Göring had his own views how this should be achieved. This is a challenging book, but as close as possible it is a real-time reconstruction of Nazi-occupation of Białowieźa, German soldiers and the Holocaust. Michel Trouillot’s words are evocative: ‘This is a story within a story—so slippery at the edges that one wonders when and where it started and whether it will ever end.’3

The acquisition of sources

The research was hindered by the absence of a central repository of records and archives to anchor the book. The grouping of documents was like different corners of a jigsaw puzzle without an original picture to bring them together. There were mismatches between known actions, where histories had percolated into myths and no bridges to span any connection between maps and documents. My doctoral research into Bandenbekämpfung doctrine was helpful, as was defining Sicherheitskrieg (security warfare) as a traditional German response to armed resistance in occupied and colonial territories; but it was not yet clear how all of this applied to the Białowieźa case.4 There was a vague outline for a case study article, but too thin to stand alone as a book. Richard Holmes recommended I pursue my post-doctoral research along multiple lines of investigation. The primary sources from six key topics included: Hitler’s Luftwaffe, the hunt and environmental history, military geography, Colonialism and Nazi Lebensraum, the Holocaust, and the war in the east. Gradually, the evidence was acquired from a variety of sources, but with a common cut-off date of 1945. This evidence was then categorized into victims, perpetrators, and bystanders. Some postwar evidence that directly contributed to the narrative was included to explain how the perpetrators escaped justice and manufactured ‘new’ lives. This methodological approach of synthesising multi-disciplinary research satisfied some but generated criticism from others.

There was also a story about the Luftwaffe records. On 3 August 1945, US Army intelligence officers interrogated Karl Mittman, formerly deputy commander of the Historical Section of the Luftwaffe (8. Abteilung). Mittman, born in Frankfurt in 1896, had served in the Great War and afterwards had established a career as an industrial merchant. In 1935 he was called up and joined the Luftwaffe. His work had initially involved publishing a history of the war in the air 1914–1918. The onset of the Second World War suspended all previous work, as the section began collecting material for the present conflict. The section also expanded, employing well-educated officers with experience in writing historical narrative. Lw. Brigadier General Herhudt von Rohden (1899–1951) was placed in overall command. Section eight had six subsections: Auswertung (evaluation), Kriegsgeschichte (war history), Wehrwissenschaftliche Gruppe (military science), Bildgruppe (photographic section), Technische Gruppe (technical) and Archiv (archives). Mittman claimed the purpose of military history was to establish the basis for a world history, a medium for the education of service personnel, and to present ‘a responsible account to one’s own war.’ He identified three categories of military history: a political history of the war, a history of the military strategy of the war, and a ‘history for the education of the people.’ During the war, the section had completed a review of the period 1939–43; fifteen annuals of air war accounts including Poland, France et al; had compiled special instructional guides for officers; and had published pamphlets on aspects of the air war. All this work and output, according to Mittman, had been carried out without political controls or interference. Then, as the war drew to a close, the section made several moves from Berlin to Thuringia, Bavaria, and Czechoslovakia. Driving from Karlsbad to Bavaria, as allied thrusts quickened, Mittman decided to destroy the material. Fifty cases reached Vorderriss near Bad Toelz, mostly maps and material regarded as ‘little importance’, were stored in a forester’s office. Mittman helpfully offered tips to the allies how the archive could be reconstructed.5

More than fifty years later, I was in the Bundesarchiv-Militärarchiv in Freiburg-Im-Breisgau, the last day of a long research trip. Frau Noske, the resident but kindly official, presented a print-out of files that had just arrived in the reading room. They were a small collection of diaries of a Luftwaffe security battalion and a Luftwaffe ‘special commando’. They were assigned to security actions against Soviet partisans in ‘Bialowies’, the German spelling of Białowieźa, during 1942–44. The battalion was the Sicherungsbataillon der Luftwaffe Bialowies zbV. The battalion was raised on 18 July 1942, disbanded on 18 March 1943. The other formation was Jäger-Sonderkommando Bialowies der Luftwaffe zbV. This smaller unit was activated on 6 March 1943, but was increased to battalion size from October 1943, and remained in Białowieźa until the great German retreat in July 1944. It was immediately apparent they were an important source. Panic: hasty photocopy requests in bulk, hatched and dispatched, in the age before digitalisation. Subsequent deflation: under scrutiny, it was apparent that the primary content was locked in obscure map references. Richard Holmes recognized this was the ‘smoking gun’ of the research, but only so long as all the evidence was collected and deciphered.6 In lieu of managing the maps, a search process was started to locate the personnel records of the men. The Deutsche Dienststelle (WASt), in Berlin, held the Wehrmacht’s card index records. The Wehrmachtsauskunftstelle für Kriegsverluste und Kriegsgefangene (WASt) maintained a complete record of combatants, casualties, and POWs for all the Wehrmacht. Alongside the names extracted from the diaries with the casualty records, a prospective list was sent to the Bundesarchiv-Zentralnachweisstelle (BA-ZNS), previously in Korneliemünster, near Aachen, to locate records. That archive held several personnel files of some officers and ordinary ranks (ORs), including postwar claims for service pensions.

In their memoirs, Luftwaffe aviators have acknowledged the tactical implications of Bandenbekämpfung for the Luftwaffe’s ground forces. In particular, the change from the defence of installations to aggressive local search and destroy actions. Hans-Ulrich Rudel recalled his airfield being exposed to Red Army probes and no longer any ‘… battle-worthy ground forces screening our front …’. As ‘Ivan’ probed, the commander of the airfield staff company, ‘gets together a fighting company drawn from our ground personnel and those of the nearest units and holds the airfield.’ Rudel observed:

Our gallant mechanics spend their nights, turn and turn about manning trenches with rifles and hand grenades in their hands, and during the day return to their maintenance duties. … Our Luftwaffe soldiers at the beginning of the war certainly never saw themselves being used in this way.7

The question of the airfields in the ‘bloodlands’ had not entirely gone unnoticed. In July 1952, US Counter-Intelligence officials began an investigation of the Vinnytsia massacre, where Soviet secret police had murdered 9–11,000 Ukrainian civilians. The grave pits were discovered in 1943 and, the Germans used the evidence as a propaganda coup against the Soviet Union. The Nazi Ministry of Eastern Affairs assigned pathologists from nations across occupied Europe. Several former Luftwaffe personnel, present when the site was uncovered, were later interrogated by the Americans. Alfred Holstein (born December 1891), from Rothenburg, remembered visiting the excavations several times and recalled how the Ukrainian mayor (a Nazi collaborator) had called them victims of their religion. He was persuaded to give a detailed testimony, which revealed he was the commander of the Luftwaffe labour battalion working at the nearby airfield. Following a period of heavy rain and rapid drainage, the ground had formed strange shapes. In May 1943 they began digging and discovered the massacre site. Georg Müller (born 1894), had served with the Luftwaffe, was transferred to the airbase in Vinnytsia and testified:

At one time, I was going from Winia (sic) to the airport when I saw many people coming down the street accompanied by SS Guards. The people were Jews (men, old women and children). They were taken to the prison. A few days later, they were taken by truck to the place of execution (approximately one kilometre from the airport). They had to undress and walk into the pits which were already dug. There they were shot. There also partisans were disposed of in the same manner.

He also recalled engaging with a group of 60 Jews—slave labour working on the airfield. He discovered they were to be shot. A truck arrived that evening (6.00 pm) and took 10 to the place of execution—8 managed to escape. He was later transferred to a Luftwaffe facility in Lemberg, in Poland, and Müller learned of an execution site in the locality. The CIC report concluded: ‘no further investigation of subject massacre is intended by this detachment unless otherwise directed …’.8

In the 1950s, former German Army and Luftwaffe generals recast themselves as honourable professional soldiers, irrespective of being among Hitler’s cohorts.9 They were praised in military histories of the Luftwaffe, which persisted in focusing upon strategy, operations and technology; affirming a reputation for elitism, rather than scrutinising the allegiance to Hitler and its darker implications.10 Marrying murderous acts on the ground to knightly aerial warfare is not difficult to establish. The behaviour of the airborne forces in Crete (1941–42) continued a trail of crimes that began in the Spanish Civil War and included bombing civilian settlements in Soviet Russia and Yugoslavia on the spurious grounds of ‘suspected’ partisan hideouts. The Luftwaffe, as demonstrated in this book, was quite capable of breaching its legal codes to commit murder, even without the vilification of racial enemies.

Engaging with microhistory

This book was conceived at a particularly lively period of historical discourse and debate. The contemporary interpretation of Hitler’s war had begun to take shape in the 1980s. For example, Omer Bartov had noted, ‘The collaboration of the army with the Nazis and its role as the instrument which enabled Hitler to implement his policies, were most evident during the war against Russia.’11 Since German rearmament in the 1950s, the story of the Wehrmacht’s complicity in Nazi crimes had been resisted. Bartov’s book was an uncomfortable reminder of the reality of the war, just as the Cold War was about to end. By the 1990s the literature was directly questioning the mass mobilisation of manpower as directed towards the Holocaust. Christopher Browning had observed, ‘… the German attack on the Jews of Poland was not a gradual or incremental program stretched over a long period of time, but a veritable blitzkrieg, a massive offensive requiring the mobilization of large numbers of shock troops.’12 In Germany, the Wehrmachtausstellung opened in Hamburg, an exhibition that explained the Wehrmacht’s participation in Nazi crimes. A controversy over the content forced the exhibition to close and one of its organisers forced to step aside.13 Hannes Heer, having stepped down from the exhibition, published his interpretation of the crimes of the Wehrmacht on the eastern front and included his essay on combating partisans.14 In 2000, I was able to discuss my ideas with Heer and soon recognised we shared similar conclusions about Bandenbekämpfung, as a means to bringing ordinary soldiers to Holocaust killing without an overbearing ideological hierarchy.

The Holocaust was also embroiled in lively debates in the 1990s. For a long time, Raul Hilberg’s three-volume study framed Holocaust scholarship.15 Then Daniel Goldhagen exploded the accusation that Germans had been willing executioners, ‘… this book endeavours to place the perpetrators at the centre of the study of the Holocaust and to explain their actions.’ He argued the ‘… institutions of killing detailed the perpetrators’ actions, chronicled their deeds, and highlighted their general voluntarism, enthusiasm, and cruelty in performing their assigned self-appointed tasks.’16 Since 1940, deportations had collected Jews from across occupied Europe concentrated them in Polish ghettos. In June 1941, the SS-Einsatzgruppen ranged across the rear areas in the wake of the German Army’s advance into Soviet Russia.17 In the Holocaust by Bullets, the SS killed or murdered upwards of two million Jews.18 From mid-June 1942 the destruction of the ghettos set off another wave of deportations to killing centres, but this also sparked outbursts of Jewish resistance.19 By December 1942, Hitler’s war against the Jews had escalated into a three-part process involving deportations, killing centres, and mass deaths. The evidence collected for Birds of Prey confirmed that Luftwaffe troops were assigned to this process.

There were other challenges to collecting evidence. During the period 1941–44, Białowieźa forest came within Bezirk Bialystok, a Nazi occupation zone administered from East Prussia. Göring’s ambition was to bind East Prussia and Ukraine in a common frontier with Bezirk Bialystok—a land bridge between the two. This represented a racialized colonial frontier of fewere than 3 million Germans under Erich Koch, ruling over 35 million people (Ukrainians, Belarussians, Poles, and others). This particular region was under-researched, but for Christian Gerlach’s published doctoral thesis, which is cited in the narrative of this book.20 In Hitler’s Empire (2008), Mark Mazower referred only to Ukraine and noted that the SS had difficulties working with Koch, who became virtually untouchable after turning East Prussia into a pro-Nazi state.21 Koch could rely on both Hitler and Göring to back him during internal squabbles. The greater challenge to my research, however, was the glaring absence of evidence about Bezirk Bialystok in the archives.

Before applying Historical GIS (explained in chapter 1) to the research, several attempts were made to construct a more traditional historical structure for the manuscript. The classic study of a German town, under Nazi rule, was also considered a viable option because it was compact.22 There were parallels of cultures, anthropology and localism. Allen claimed his ‘microcosm studies’ were unrepresentative of the Nazi regime but encouraged detailed analysis, which initially made it an important option. The closely relevant study was Christopher Browning’s Ordinary Men (1992), the study of a police battalion in the Holocaust.23 The book examined records from Federal German investigations, compiled from perpetrator interrogations and testimonials conducted more than twenty-five years after the war. Browning concluded the Nazis had unleashed a ‘blitzkrieg’ against the Jews, and ordinary men had carried out the killings. There were parallels of scale between police and Luftwaffe battalions, but whereas Browning could construct a case based on postwar testimonies, this was not available for a study of the Luftwaffe. Memory-based evidence has limitations, even with Federal investigations, but the greater problem was the lingering myth of the ‘clean Wehrmacht’, which included the Luftwaffe. Overcoming the myth was challenging.

The impact of the Historical GIS research is explained in detail in ‘Reading Maps Like German Soldiers’ (chapter 1), but it should be recognised that it was central to redirecting the research. The final microhistory version adapted for the book as a consequence of working with the GIS maps. Several scholars were identified as endorsing the benefits of microhistory long before its actual appearance as a specific methodology. Eric Hobsbawm defined ‘grassroots history, history from below or history of the common people’. This is referred to as Alltagsgeschichte by German historians or everyday history.24 Hosbawm’s Marxian interpretation of ‘history of the common people’ was a dialectic that might be applied to the history of the common soldier. In comparison to Hosbawm’s observations about the traditions of oral history to the working class, similar characteristics exist for the common soldier. The lowly soldier’s social structure was confined to a traditional militarised hierarchy, with orders from above forcing ‘confrontation or co-existence’ with officers and NCOs. To construct an interpretation of how the soldiery responded to Nazi dogma required a deeper understanding of the Wehrmacht beyond the battles and operations. This also involved an understanding of the cultural transformation from conventional combat to occupation, and vice versa, with some comprehension of how the soldiery survived the war beyond the usual glib interpretations of luck. Hosbawm’s ideas greatly suited the social history of the soldiery.

A wholly unexpected outcome from my research was the prominence of the German hunt in shaping events (on this see chapter 2). This coincided with a new study that advised: ‘military history, … is a promising candidate for … microhistory’, and later added ‘military history gives ample scope for the microhistorian.’25 This was a significant theoretical development, but there were no examples to support the claim. The application of microhistory in Holocaust history also illuminated how the intimate scrutiny of Nazi perpetrators could transcend everyday life and everyday killing.26 These microhistories seemed to fit the environmental and forestry conditions of Białowieźa. The conditions had formed a peculiar impression of Białowieźa on the Germans, which they dubbed Urwald Bialowies. The Mammal Institute (Białowieźa) had published several important publications, which have discussed life during the occupation.27 Historically, forestry and hunting have been dominant themes in German literature for centuries, while foreign observers have been rather whimsical about the national fixation with ‘gloomy forests’.28 The weight of forestry literature threatened to overwhelm the research for this book, but it should be recognised that the power of Białowieźa dominated the collective mindset of the Germans.29 Throughout the Luftwaffe war diaries, there were constant references to Urwald Bialowies, in almost an arena like context. Birds of Prey has attempted to reproduce that notion of an arena of killing, where the Germans imagined themselves as warriors of antiquity.

The hunting culture was politicised by Göring to serve as a code of honour, which enforced the operational dogma in Białowieźa. Senior hunt officials perpetrated genocide from their first orders for extermination, which continued for the duration of the occupation. The hunter’s mission was set by Göring, but their actions at the local level were defined by individual responsibility. Beatrice Heuser recommended pursuing a deeper examination of hunting and war through Barbara Ehrenreich’s Blood Rites.30 This ground-breaking interpretation of war and hunting led to further reading. In particular, Simon Harrison touched on much darker kinds of hunting and human behaviour in war.31 Under the Nazis, the German hunt turned into an elitist social class. One observation with hindsight, these findings could have been contextualized within Michel Foucault’s theories of power and discipline. An etiquette of power shaped the mannerisms of the hunters, especially in their relations to non-hunters. The hunt’s social elitism, in the absence of monarchy and aristocracy, was directed towards the ritualisation of professionalism. Foucault’s doctors and patients could be almost role-reversed into the hunters and non-hunters. These threads formed an image of the naked display of power and professionalism, as depicted in the symbolism of the ‘hunter-warrior’ of Luftwaffe propaganda, labouring with genocide, in the wilderness arena of Białowieźa.32

The necessity to conduct field research in Białowieźa came from reading Riding The Retreat. In the preface, Holmes discussed his ‘growing reservations with what we might term ‘arrows on maps’ military history’ and being drawn to the ‘microterrain, that tiny detail of ground and vegetation that means so much to men in battle.’33 Holmes had previously engaged with the history of memory through the anecdotes of soldiers. Both Firing Line (1985) and Dusty Warriors (2006) were influenced by memory, the ‘other soldier’ in the case of the former, and himself in the latter as an observer on the ground. Holmes listened to veterans after the Falklands War in 1983, but in 2005 gave an impression of being on the ground in Iraqi. This transformation in Holmes’ writing, from listener to witness, was a lesson in historical change, that went largely unnoticed in reviews. A further contemporary impression of the dichotomies of military culture came from The Junior Officers’ Reading Club (2010). The author warned the readers that incidents in war are not recalled in exact detail. Hennessey reflected upon a war from yet another standpoint of soldiers’ responses during a hostile occupation. There are always doubts over the accuracy of reports and this was more prominent in wartime where accounts were often accepted at face value.34 There was one important study that could not be incorporated into the research findings. Thomas Kühne has written extensively and profoundly about soldiers within the context of identity and comradeship.35 Repeated attempts to incorporate his ideas failed due to fundamental gaps in the evidence. This was primarily due to the lack of personal evidence of the Luftwaffe soldiers, their shortened periods of service together, and the absence of any identifiable primary groups. In the final version, it was a collective of Hosbawm, Holmes, and Hennessey that pointed the way. The consistent reference to documentary evidence, but the caution of the unreliability of the bureaucracy underpinning that evidence was a constant finding in my research.