Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

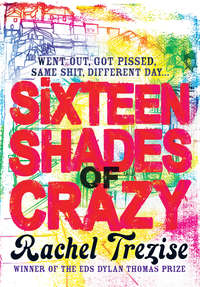

Kitabı oku: «Sixteen Shades of Crazy», sayfa 2

3

On Monday, Ellie boarded her 7 a.m. train with the usual commuters: a middle-aged administrator at Ponty College and a bricky working down the Bay. They were the only three people awake in Aberalaw at that time in the morning. At 7.55 she alighted at Cardiff Central Station, the nearby Brains Brewery coming to life for another sun-soaked shift, the pungent stench of the hops saturating her twenty-minute speed-walk to Atlas Road. There she sat in a stifling workshop, sticking stickers on mugs while the rush hours whizzed past the yellow bricks of the city.

There was a crisis going on with the Alton Towers batch. They needed another five hundred by the end of summer but the Ceramics department couldn’t get the colour right. Ellie was bored of the stupid picture: a navy turreted castle with red fireworks in the background. The mugs were orange and the castle kept coming out purple. It was because the kiln was set at the wrong temperature. Everybody on the floor knew it. But the management were adamant it was Safia and Ellie’s fault. Jane was trying to stop them using hand cream, stop them eating crisps in case they got gunk on their fingers; all sorts of screwed-up rules it was illegal to instate. The desks were stacked with tray upon tray of orange mugs, all waiting for quality control. They even had a mini-skip in which to throw the rejects, smashing each one first in an attempt to prevent light fingers. Ellie had jokingly offered Jane a majority percentage in a spot of bent trade but Jane had threatened to report her. Jane, who was Ellie’s sister, had been the Ceramics manager for seven years. She was obnoxious to start with, but the job had pushed her to the edge. The factory floor was a breeding ground for paranoia. You had to keep watching your back because everyone around you would do almost anything to defend their own menial position, bereft of the courage to go and try something new. It was like a prison cell; the guy next to you initially appearing to be another hapless fool, then twelve months later turning into a loathsome psychopath whose face you dreamt about mutilating with a craft knife you stole from the art studio.

Safia threw a chewing gum at Ellie. It hit her on the cheekbone then landed at the bottom of her glue trough with last week’s tacky scraps of paper. Ellie fished it out and threw it back at Safia, a new layer of gloop staining the sleeve of her crisp white blouse.

Safia laughed. ‘Yous have a good weekend?’ she said. She was a tall Pakistani girl with clumpy mascara. She’d ambled into the factory and sat at Belinda’s desk, a week after Belinda had walked out. For the first five days she’d complained that the transfers sent in from the cover-coaters were too thin, or too thick, that the mugs were chipped and discoloured. Ellie’d liked Belinda because Belinda danced incessantly to the music in her headphones, ignoring everything Jane said. She’d had the words Fuck Work inscribed across the bust of her tabard. But Safia was pedantic.

One stormy Tuesday morning following a bank holiday, Safia and Ellie were the only daft cows who’d turned up for work. Forced to sit in the workshop together at lunch, chewing oily tuna sandwiches from the newsagent on the corner, Ellie reluctantly warmed to Safia’s worrisome and naive nature; the way she thought she’d never get over her first love, a U2 fan from Caerphilly. She was born and raised in Cardiff, the essence of the city audible in her nasal words. Her family had sent her to Manchester for two months during a perplexing adolescence and her mother had taken her to Pakistan once to meet her grandmother. Safia had cried to come home long before the four weeks were spent; screamed on the first day, scared shitless by lizards climbing up the living-room walls. She was struggling to balance her life between her Muslim family and extended Western social circle. A difficult situation arose every time someone mentioned going to McDonald’s for lunch or offered her a glass of white wine, endless bickering at home about trouser suits, uncomfortable conversations elsewhere about engagement rings and suntans.

Ellie shrugged now. ‘Fine,’ she said.

Safia copied the gesture contemptuously, unsatisfied with the answer.

‘Fine,’ Ellie said, again. ‘Went out, got pissed. Same shit, different day.’ She didn’t have the energy for a discussion about it. Her head was still fuzzy with the phet comedown. She hadn’t done powder for years, wasn’t used to the dizzying after-effects.

She picked a new mug from the pile and gently ran her fingertips along the circumference, feeling for imperfections. She peeled a decal from its backing and wound it around the mug, squinting at it as she ironed the air bubbles out with her tongue-shaped smoother. Gavin dropped a mug on the floor and Ellie looked up to see if it had smashed. It had, but he continued to work regardless, struggling with the direct print machine. He was a solid man with a girlfriend he didn’t like and twins on the way. He made mistakes and stuck by them, held his head high, took the bacon home. He was wearing a Cardiff City football T-shirt, the season fixtures printed on its back. It was a reject from the T-shirt department. Nobody wore their own stuff to work unless the only seconds out were England sweatshirts. She knew the fixtures now by heart. They’d both worked overtime fourteen days in a row. Gavin was saving for a double buggy and Ellie had to make-up Andy’s half of last month’s rent.

In the beginning, Ellie had been impressed by The Boobs. Andy was adamant that they were going to make it and Ellie had no reason to doubt him. Ambition was written through her own bones like a stick of Porthcawl rock. She knew what it was to want rabbling cities and hectic skylines, to have dreams about seeing the back of the valleys. So when she moved in with Andy, only to discover their joint income didn’t stretch to the lease, not even on a crumbling two-bedroom in Aberalaw, Ellie was happy to quit freelancing in favour of a steady income. She figured that when the hard work was done, she’d be one half of an über-couple, renowned for throwing vegetarian dinner parties at their chic Greenwich Village brownstone. That was over a year ago, and she felt as though she’d stuck enough stickers on mugs to last four lifetimes.

‘Bastard!’ Gavin said as another mug spun out of his grip. It shattered on the concrete floor. He bent down to retrieve the fragments, throwing each one into the mini-skip with an expletive.

‘Are you going to tell me about your weekend?’ Safia said, eyes narrowing to slits. ‘I thought Andy was coming home on Saturday.’ Safia didn’t have a social life. She spent most of her leisure time cooking pasanday for her family. She watched Coronation Street. She meticulously clung to the details of Ellie’s existence like a tabloid journalist unearthing the secrets of an A-list celebrity.

Every day, Ellie ran through an inventory of the things she’d done since she’d last seen Safia: what time she’d got home; what she’d eaten for dinner. Safia’s favourite subject was Andy. If he and Ellie had had sex, Safia needed to know the position, the point of orgasm, the colour of the sheets. Over time Ellie had begun to embellish these little narratives, so that she’d eaten scallops instead of battered cod, worn negligees instead of fleece pyjamas, got twenty minutes of cunnilingus instead of nothing. It was inevitable: Safia’s appetite for romance was insatiable, but Ellie had lived with Andy for a long time – they sometimes couldn’t be bothered to have sex. And today she wasn’t thinking about Andy at all; her mind’s eye was busy with the stranger’s image: his chaotic hair, his treacle-black eyes, his lily-white teeth.

It made something in her tummy swell, like a fist of dough in an oven. She was wondering why his girlfriend wasn’t allowed to drink vodka, wondering what his name was, wondering what the hell he was doing in Aberalaw. These little mysteries were far more compelling than anything to do with Andy, more compelling even than the idyllic fantasy life she had created for herself and conveyed on a daily basis to Safia. The stranger arrived seamlessly in her consciousness. One minute she’d been missing Andy; the next, there was some long-haired extraterrestrial who had materialized from thin air.

‘El?’ Safia said, as if from some distance.

Ellie sighed, annoyed by the interruption. She considered telling Safia about the stranger, but then quickly dismissed the idea. Safia was as chaste and delicate as the foil on a new coffee jar. She was religious. She’d been conditioned to ignore temptation, neglect her own feelings, banish any rebellious thoughts that accidentally found their way into her head. She wouldn’t understand Ellie’s predicament.

‘Yeah, Andy’s home,’ Ellie said. ‘And the band had some good news. A Radio 1 DJ liked one of their demos. He wants them to go on his show.’

‘Wow,’ Safia said. ‘They’re going to be famous!’

Behind her the fire exit opened. Jane appeared, heels clicking on the concrete. She stood next to their adjoining desks; hand on hip, counted the trays of mugs piled up from the floor. She noted the total down on her clipboard, her glasses slipping down her nose. ‘You know we need a whole new batch of these packed and shipped by the end of August, don’t you? Save your chitchat for your coffee break.’

4

At six on Wednesday night, Ellie was on her way home from the factory. The sun was reflecting on the bronze statue in the middle of Aberalaw Square. It was a Dai-capped miner, one arm clutching his Davy lamp, the other curved protectively around his wife and babe-in-arms. It was hard to distinguish one limb from another, especially if Ellie had been drinking in the Pump House. As Ellie got close to the pub she saw Rhiannon standing on the doorstep, talking into her mobile phone, a pair of pinstripe bell-bottom under her white hairdressing tunic. Ellie began to walk faster, trying to dodge her, scurrying past the statue towards the safety of Woodland Terrace. But a metre away from the pine end, Rhiannon’s voice rang through the village like a marauding police siren. ‘Oi, mush, come back by yere a minute.’

Ellie reluctantly turned around and walked back to the pub, her duffel bag jerking on her shoulder. She stood in front of Rhiannon while Rhiannon finished her conversation and flipped her phone shut. ‘Kelly’s gone to the dentist to get her rotten teeth out,’ she said. ‘Too many fuckin’ sweets or somethin’. Fancy comin’ in yere with me for a drink or what?’

Rhiannon was bordering on alcoholism, carried half-litre bottles of spirits around in her handbag. But she always needed someone to drink with. Misery loves company. Kelly was her teenage assistant at the salon; usually they went out together every night after work. Ellie picked at a glue stain on the thigh of her khaki cammos. Andy didn’t like her drinking on week nights; he didn’t like her drinking without him.

‘Well?’ Rhiannon yapped.

Ellie jumped.

‘Ewe ’avin a bloody drink or not?’

Ellie followed Rhiannon through the pub and into the games area. Rhiannon sat at her table, the surface of it obscured with wineglasses full of Liebfraumilch, the house white. She picked one of the glasses up and gave it to Ellie, then took a sip of her own. ‘I’ve got a game of pool on the go,’ she said, pulling a worn cue out of the umbrella stand. ‘I’ll break if ewe don’ mind.’

Dai Davies looked up from his newspaper. ‘Go on, bach,’ he said, shouting across the pub, holding his beer stein up in the air. He was a fixture at the Pump House bar, a retired cat burglar who delighted in malicious hearsay. He was also Rhiannon’s uncle.

Rhiannon held the cue against herself, the tip burrowed between her double-D breasts. She squinted at it and puffed on the chalk then ducked at the edge of the table, one leg kicking out at the rear, her cropped bell-bottom revealing a thick band of brown skin. ‘Italian coloured,’ she called herself. But she wasn’t Italian. Her parents were as Welsh as they came; career criminals from the Dinham Estate. The man who Rhiannon swore was her father, despite his being white and her clearly being mixed race, had been murdered in his prison cell when she was a kid. But not before giving her some cock-and-bull history lesson about south Walians originally being naturally dark-skinned, a story she still used to defend herself whenever someone from the estate called her a nigger.

The white ball rolled into the pocket without hitting any of the colours. Rhiannon passed the cue to Ellie. ‘What d’yew reckon about this radio show?’ she said. ‘Ewe know about stuff like that, El. Am I gonna be rich next week or what? Cause I’ve had it with that bloody salon, I ’ave. Ewe can catch all sorts of shit messing with people’s ’air. Nits, skin diseases, ’alf of those inbreds from the estate got AIDS. I should get danger money for what I do.’

Ellie shattered the virgin balls, exposing a purple stain on the green felt where Siân had tipped a pint of cider & black a few months earlier.

‘I tell ewe,’ Rhiannon said, ‘when ’ey make it I’m gonna have a big bloody mansion built on Pengoes Mountain, a big bloody electrocuted gate to keep the scum from the estate out.’ She clapped her hands, like a seal doing tricks for a piece of fish. Pool games with Rhiannon were not meant to be won. They played by loitering around the table for three-quarters of an hour, talking about whatever Rhiannon wanted to talk about, taking it in turns with slow, aimless strikes. Ellie daren’t put any effort into it. She was afraid of beating Rhiannon, afraid of what Rhiannon’s reaction might entail. If Rhiannon was anything she was a sore loser, so Ellie saved her concentration for pool games with Griff. Nothing annoyed Griff like losing a pub game to a girl.

‘Bloody tired I am,’ Rhiannon said. ‘Marc’s fault it is. Came home wanting six weeks’ worth of nooky in two days.’ Ellie cringed at the mention of nooky. Rhiannon was always fraught to portray herself as a hip, 20-year-old fashion aficionado. She read articles in Kelly’s magazines about John Galliano and Stella McCartney, was always dripping in fake haute couture. But her vocabulary perpetually belied her disguise. Words like nooky and mush and Billy Whizz. Her voice came straight from the estate.

‘Three times in one fuckin’ night,’ she said. ‘That run in the family or wha’?’

Andy and Marc were brothers, Andy the elder by a year, which meant that Ellie and Rhiannon were very nearly sisters: sisters by common law. There was a time when Ellie could stand Rhiannon, when she didn’t cross the street to avoid her, when she thought she was a suave and quick-witted femme fatale. Marc had met her eight months ago at a gig in Penmaes Welfare Hall, one of those ones where The Boobs stood in for the resident cabaret act, a glam-rock cover band called The Poseurs. As soon as the locals worked out that Andy didn’t know any T-Rex riffs, The Boobs got bottled off. One dour Sunday afternoon, a black woman had appeared on the dance-floor, strutting around on her own, a miniature bottle of Moët in her fist, a luminous pink straw, shaped like a treble clef, sticking out of the top. She was wearing a tiny yellow A-line dress and a pair of fishnet stockings, the black lace bands at the top of them exposed. Her accent was so Welsh, so cordial and melodic, it would have seemed foolish to interpret it as anything other than endearing.

Ellie clearly remembered thinking that she could do with a friend like Rhiannon. It gave her hope to think that such a sophisticated specimen of being existed in a place so overcrowded with rednecks. Of course that was all positive prejudice. Rhiannon turned out to be the most bigoted person Ellie’d ever met: a brainless, reckless tart. There was no champagne in that bottle. It was just something she used to carry around in her counterfeit Prada handbag, one of her good-time-girl props. But she’d given Marc a lift home in her red sports car and he’d never been the same since. Ellie always joked that she must do something really special in bed.

‘I mean,’ Rhiannon said, swallowing a big gulp of wine, ‘does Andy have to shag ewe every night?’

‘He would if he could,’ Ellie said. For the most part, Andy and Ellie’s libidos worked on different time zones. His was on Greenwich Mean Time; hers was on Central Daylight. They hardly ever converged. ‘Every night I hear him brushing his teeth in the bathroom with his electric toothbrush. That means he wants it. He told me once that it is a family trait; that it comes from his mother. Gwynnie. Can you imagine? Apparently she’s a real goer.’

Ellie expected Rhiannon to laugh but she had already lost interest in the subject. She was standing in front of the mirrored beer advert, arranging her hair so it stuck up like the head feathers of an exotic bird, her wineglass held in the air as though she expected an attendant to come and fill it. She hadn’t expected an answer. She thought she was the only person in the village who had sex, and was therefore the only one qualified to speak of it.

They left the game half finished when Rhiannon decided she was too tired to play. She propped the cue against the wall and it immediately fell and crashed on the parquet floor. She rolled her eyes as she plonked herself down on the stool. ‘It’s that powder as well, see,’ she said. She curled her hand around her jaw, hiding her mouth from Dai Davies’s eye-line. ‘A couple of dabs on a Saturday and I’m not right till Wednesday.’

‘You took quite a lot of it,’ Ellie said, safe in the knowledge that sarcasm went right over Rhiannon’s head.

‘Bloody good stuff it was,’ Rhiannon said. ‘I’d like to know where ’e got it from, El. Eighteen bloody months I’ve been trying to get hold of some whizz like that. Nothing!’

‘Scotland,’ Ellie said. She knew Rhiannon wasn’t the sharpest knife in the drawer, but it was obvious. ‘Marc brought it back from Glasgow.’

‘No,’ Rhiannon said. She shook her head, sprigs of her carefully placed hair falling flat. ‘Marc din’t have enough money to get home. Griff’s asked ’is mammy to put a loan in his account for petrol. They’d still be on a fuckin’ motorway somewhere otherwise. I bought the speed, from that English bloke, with the long ’air. ’E was in yere on Saturday with ’is missus. Just moved yere, ’e ’as, sold ’is farm in Devon or somethin’. Bloody good stuff it was, El. I don’t wanna be lining some English twat’s pocket, do I? Whass ’appenin’ in Cardiff? Anything about?’

Rhiannon was talking about the stranger. ‘He’s not from Devon,’ Ellie said. ‘He’s from Cornwall. There’s a difference.’ She looked Rhiannon straight in the eyes, something she didn’t do very often. ‘Are you sure you got it from him?’

‘Yes!’ Rhiannon said. ‘I saw ’im on the square on Saturday morning. ’E was doing a deal with a kid from the estate. I went right bloody up to ’im, asked ’im what ’e ’ad. He’s got disco pills too, he told me.’

That’s how Rhiannon knew him. That’s why she kept touching him on Saturday, as if he was her pet dog. He didn’t look like someone who sold drugs. Street pushers wore baggy, food-stained jogging-bottoms. They lived in unfurnished flats on the Dinham Estate. Ellie quickly imagined what kind of job her ideal man would have. He would be a painter or an architect, someone with a pencil in his hand. But this was Aberalaw and drug dealing was as good a job as anyone could hope to get. ‘What’s his name?’ she said.

Rhiannon snuck a glimpse at Dai. He was reading the local newspaper, studying the ‘Look Who’s Been in Court’ column, looking for stories he could exaggerate. Jenny Two-Books, the assistant from the betting shop on the High Street, had just arrived to collect her extra takings. She ran her own service for the alkies who were too drunk to walk to the shop. ‘Johnny,’ Rhiannon said. ‘Johnny somethin’.’

‘Where does he live?’

‘I don’t bloody know, El. What’s it to ewe anyway?’

Ellie felt her cheeks redden. She looked down at the assortment of wineglasses on the table, trying to hide her face from Rhiannon, but Rhiannon had already detected something in her enquiry. ‘Ewe don’t fancy ’im or somethin’, do ewe, El?’

‘Don’t be stupid,’ Ellie said, not looking up from her drink. ‘I love Andy.’

Rhiannon lifted the egg-cup-shaped glass to her mouth, peering intently at Ellie over the rim. ‘Aye,’ she said. ‘I love Marc an’ all. I love Marc as much as ewe love Andy, don’t think that I don’t. An’ if I ’ear anyone saying I don’t love Marc, I’ll fuckin’ batter ’em.’ Whatever that was supposed to mean. Ellie shrugged and reached for her glass.

Rhiannon beat her to it. ‘I’ll get ewe a fresh one,’ she said, giggling, the angry smirk on her face fading from the bottom up. ‘But ewe’ll ’ave to remember ’ow many ewe owe me. I can’t afford to keep us both in wine. Things ain’t that good at the salon.’

Dai Davies folded the newspaper down on the bar. Accidentally, Ellie caught his eye. He grinned at her lecherously, made a creepy clicking noise with his slick tongue. Ellie shivered. They were psychopaths, the whole family.

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.