Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

Kitabı oku: «Sweet Agony»

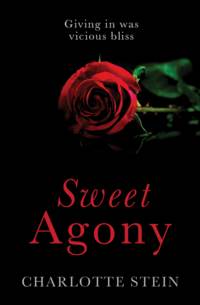

Sweet Agony

CHARLOTTE STEIN

A division of HarperCollinsPublishers

Copyright

Mischief

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London, SE1 9GF

Copyright © Charlotte Stein 2015

Charlotte Stein asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Ebook Edition © 2015 ISBN: 9780007579518

Version: 2015–04–21

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

More from Mischief

About Mischief

About the Publisher

Chapter One

The advert says ‘Seeking Housekeeper’, which I guess sounds innocent enough. Even the other stuff underneath is only pretty weird, rather than very. It just asks for excellent tea-making skills, and no social huggers, and an enthusiasm for order, and to me all of those things sound reasonable. They don’t ring alarm bells in my head.

But the house does.

I sit for around ten minutes across the street from it, in my battered little Beetle with the red vinyl seats. Part of me really, really wanting to go in and save my own skin. But most of me too scared to do anything but stare in horror. Honestly, if you looked up Dickensian in the dictionary you would find this place. It looks as though someone called Mrs Migglethwump lives here, after her husband ran off with the maid on their wedding day.

The front of it is the kind of grey you only get after natural disasters. Some apocalypse happened to this place and this place alone, and now it sits like a bad tooth in a mouth of pristine white ones. It even seems vaguely crooked, in a way that should be impossible. The other houses are ramrod-straight. There is no space for it to slant to the side – it just looks as though it does.

Malevolence is probably making it happen. I think malevolence might be making a lot of things happen. All the windows are blank, black eyes, and each one seems to follow me wherever I go. I glance away for a second and can almost feel them, pressing into my body. Then I turn back and they pretend to be all innocent again. They never watched me reach for the newspaper on the seat beside me. They are just windows, busy minding their own business. There is nothing to worry about here.

Apart from the garden that time forgot.

Lord, the garden that time forgot. I get out of the car feeling strong and brave, almost proud of myself for getting so far in the face of this hideousness. And then I see the garden, and falter. My feet seem suddenly lined with lead. I think of what I will have to do to get across what is really only a small square at the front of the house, and have to wonder if this is all worth it. Those nettles alone look positively ravenous. Somewhere in amongst all the rubble and rambling weeds, I can see what looks like a bike.

I put one foot in there and I’m going to be eaten alive. They will probably find me three years later, with seven-foot dandelions sprouting out of my eye sockets. One false move and the hidden portal down to hell might swallow me whole – and that isn’t even the worst of the problems here. No, that comes when I attempt to get into the garden anyway.

And realise the gate is rusted shut.

If I want to get in, I am going to have to climb over the thing. I am going to have to hike my skirt up and lift my leg like a dog doing a wee, and when I do my underwear will be on display. Every eye in that evil house will see the two holes near the sagging elastic and the faded image of Spiderman on the bottom, then most likely curse me for all eternity.

All of which seems pretty silly, until I actually start my attempt. I bunch my skirt up into my fists and begin to step over, and just as I do I hear the person who lives here. They make a sound like someone moaning from inside some terrible abyss, so cold and alien that for a second I barely recognise it for what it really is.

Then it rushes over me in a hot flood: laughter. The person inside is laughing at me, in the bitterest, haughtiest way possible. You could stick that awful noise in the House of Lords and have it shout at the Prime Minister. It could attend a swanky soirée entirely independent of the person it comes out of, and no one would blink an eye.

But I do my best not to care. I grit my teeth and keep going, no matter what he does to throw me off. I think he actually snorts when I almost lose a shoe to a particularly vicious patch of brambles, and I know he laughs again at the state of my tights after a fight with the lost bike. This time it rings out as clear as a bell, if bells were super haughty and filthy rich.

Yet somehow I still make it to the door.

Only to be told:

‘Not today, thank you.’

He even sounds delighted to get the opportunity to say it. I can hear it in the back of his voice, buried beneath what can only be described as the most cultured accent the world has ever known. I swear my social standing plummets seventeen levels just listening to it. I feel as though I need to bow, and not just because of the sheer wealthy weight behind each of his words.

There is also the fact that he sounds amazing.

Oh, my Lord, no one in the history of the world has ever sounded as amazing as he does. For a second I actually overlook the ludicrous rudeness and just drown in that rolling, velvet-lined tone. He could probably read the news, if the news was specifically designed to make women come on command. Every syllable seems dipped in smoke, so deep and rich I stand there speechless for a second.

And it may well be a good thing that I do.

I think I would probably have gushed over that voice, if he’d given me another second. The words holy crap you could sear skin with that thing are on the tip of my tongue, and only stay there because he goes first.

‘You must be aware that you are completely inappropriate for the position,’ he says, at which point I realise that I’m supposed to be angry. He might sound like sin itself, but he is also quite clearly an enormous arse. I mean, I know that my tights are laddered and my clothes have holes in and I have the broad, plain features of a person not fit to shine his shoes.

But he need not have pointed that out so bluntly.

He could have pretended to be polite, like a normal person.

‘I had no idea dusting a shelf was such an advanced science these days,’ I say, and it comes out so dry it startles me. I had no idea that tone of voice was in me. Most of the time I back away from an argument, and it seems like that should go double here. I am standing on the expensive doorstep of a man with a voice like cigar smoke, trying to get a job that might possibly save me from starvation.

I should really feel more fear – and most likely would.

If I had anything in the world left to lose.

‘If you were appropriate you would be fully aware that it was.’

‘I was just testing you. Really I know how to use the lasers.’

‘You intend to use lasers to remove dust from my shelves?’

‘All the most professional dusters are doing it these days.’

‘I get the distinct impression you believe you are amusing. Therefore I feel I should inform you that I find amusing people tedious in the extreme.’

‘Oh, you need never worry. This is a shocking amount of amusing for me.’

‘Why do I suspect that is supposed to be a joke too?’

‘Possibly because you’ve never heard anyone being funny before? I bet most people just bow and scrape and tell you about their time at Eton.’

‘Yes, and they were all wildly inappropriate too,’ he says, and I’m ready to answer back. In fact, I think I might even be enjoying answering back. It makes my bones rattle and my dad’s words ring in my ears – ‘why do you have to be so clever?’ – yet somehow I don’t want to stop. I want to see what he says next. I want to be free to say silly things about lasers, and somehow his pomposity lets me.

I would probably keep poking and poking it for ever, if it were not for the sudden realisation that sinks into me, after those words of his. He said ‘all’, I think, as though it might not just be me and my awful coat and my Yorkshire accent.

‘How many people have you turned away, exactly?’

‘I hardly see how that is any concern of yours.’

‘You hardly see how it might be a concern of mine that I drove all the way here with my last drop of gas to get a job I desperately need only to discover that the person hiring might be completely unwilling to ever hire anyone?’ I ask, and then there is a sullen-seeming silence. Clearly, I hit on the right thing here – but he refuses to admit it.

‘I will have you know I let in many, many applicants. And despite her numerous flaws I almost hired the girl from Sweden.’

‘I feel like you are making up the girl from Sweden.’

‘That is a frankly outrageous charge.’

‘But you did though, right?’ I try, expecting further failure.

Yet I get this wonderful reply instead:

‘Yes, and I would appreciate you explaining how you managed to discern such a thing through a door while being harangued by a man who expects you to use lasers to dust.’

I just love that he takes the laser thing and runs with it. I feel as though I lobbed a ball of insanity at him and he just caught it and lobbed it back. No one has ever lobbed my ball of insanity before. I barely dared reveal I had one in my possession, prior to this discussion. Usually I keep it hidden, beneath seventeen layers of pretend ignorance.

But why pretend with him? He clearly values smartness.

I even hear the eagerness in his voice, after I tell him that it was a fairly obvious guess to make. ‘Tell me all the ways in which it was obvious,’ he says, like some word vampire starved of sentences by boring girls from Sweden. And, luckily for him, I am almost bursting with every letter in the English language. I’ve spent my whole life feasting on books and books and books, with no one to talk to about what I’ve found there.

He can have it all. Right now, right here on this doorstep.

Here are my guns blazing. Here is me going out in a blaze of glory.

‘If you intended to hire someone you would not be enjoying haranguing me quite so much. And you might have cleared your path. And you definitely would never have laughed when I stepped over the gate, or told me I was inappropriate before I spoke a word, or made up a girl from Sweden. Also you probably would have opened the door,’ I say, and for just a second I feel sure I’ve blown it. I spent too long being too smart. Now I’m no longer smart enough. I failed at the final hurdle, and will have to go away and starve in my car.

I even start to turn, but then I hear his voice. It’s like heavenly shades of cigar smoke falling. Like the trumpeting of a dozen angels, come to save me from this abyss.

‘I have no hope that you will succeed,’ he says.

I guess he has no idea that I already have.

Chapter Two

I try to respond in a normal manner to all of this. But the trouble is, everything just gets more fascinating from there on in. For a start, he somehow disappears before I can get through the door and see his face. I find myself in a narrow, slightly slanting hallway, so utterly alone I could have stepped through a portal to the netherworld.

And the room past the open door to my right does nothing to dispel this impression. I am ready to gasp when I see it, and probably not in the right way. Most people, I expect, faced with this, would be appalled or amused or feel some other emotion that I apparently don’t possess. Instead I think I reach something like giddiness. A grin immediately tries to smear itself all over my face, and only the sense that he must be watching somewhere hauls it back.

He must be behind some secret wall, spying.

Because that is what the room looks like – as though it has secret walls that someone could spy behind. It seems to have around twenty-seven corners, even though I could swear that twenty-seven corners are not possible for a fairly small rectangle. There should be no more than four, I think, yet, when I take a step in, twelve more jump out at me. I could swear the sides of the fireplace are that illusion where you step closer and a passageway is revealed.

I suppose the wallpaper helps. It looks at first glance to be made up of a million skulls, and it is no relief to realise they are just ornate black flowers repeated over and over. My eyes still cross when I look at it. I have to glance at other things, only to find that other things are just as brilliant and terrifying.

He has an old-fashioned street lamp in one corner, complete with a flickering candle behind the dusty glass panels. In fact, the street lamp is the only thing lighting the room. The sun has no chance of filtering through the closed and extremely heavy purple curtains, and where a ceiling light should be there is just a blank space.

But that only makes everything seem stranger and even more mysterious. It’s like looking through syrup at a scene from the nineteenth century. There are thick rugs on the floor and the fireplace is real and as I stand there I realise the sound I’m hearing is the somnolent tick of a grand old clock on the mantel.

By the time he speaks I think my limbs have gone a little weak. I want to sink into this heaven, and his voice does nothing to assuage that. It rolls into the room in one long ribbon, so deep and sinuous I could almost overlook his instructions. I could, if they were not completely bizarre and insane.

Oh, God, I think he might be insane.

‘Turn the chair beside you around, so that it faces the window. Once you have, you may be seated,’ he says, which I suppose is not that bad really. However, when you put it together with him speaking those words through a door, it all gets a lot stranger.

They suggest only one thing: he does not want me to look at him. He disappeared on purpose, so I could not catch so much as a glimpse – an idea that sounds bonkers but is pretty much borne out by all the evidence. I mean, what other explanation could there be? I thought he just wanted to leave me fumbling and unsure, then make some grand entrance. He seemed the type to make a grand entrance.

But now I feel less certain.

Maybe he has a problem, I think, a terrible and awful problem that he can never let anyone see. I read the other day about a man with a foot for a hand, and although I feel fairly confident that this was a lie it’s about all I can imagine now. He will come in with shoes on the ends of his arms and gloves on the ends of his legs, then scream in agony when he sees I ignored his instructions.

All of which is utter nonsense, I know, but I just go ahead and sit facing the window anyway. It seems best, considering all the real problems that he might actually have. He could have had his face blown off in the war, or some form of agoraphobia that means he can’t cope with people looking, and despite the high probability that he is just a haughty arsehole I want to respect these possible issues.

Though I will admit that it gets hard when I hear the door open. I want to turn so badly I can feel it in my teeth. I have to clench everything just to keep myself contained, but parts of me still do their best to escape. My heart almost lunges out of my chest at the sound of him drawing up his own chair. All the hair on my head seems to be prickling and bristling, as though he had taken a handful of it without me knowing.

And then just yanked.

‘I can see you fidgeting, you know.’

‘I would probably be doing it less if we were having an ordinary interview.’

‘And what would you consider an ordinary interview?’

‘Both of us occasionally making awkward eye contact.’

‘Sounds ghastly, if you ask me.’

‘I doubt I ever would.’

‘Would what?’

‘Ask you. You seem like the very last person to discuss the possible merits of eye contact with, considering our current positions.’

‘I have very good reason for this request.’

‘And that reason would be?’ I try, even though I know it will fail. I understand it will before he even emits his little snort of derision.

‘You ask too many questions.’

‘Well, I just thought if I was your housekeeper…’

‘If you were my housekeeper, what? You will feel the need to ask me irrelevant things in a constant and ever more intrusive manner?’

‘I would have thought it was necessary. I mean, what if you have a foot for a hand? I might accidentally kneel down to put on your shoes, only to find fingers where your feet should be. That seems at best like an embarrassment we could avoid,’ I say, then almost marvel at myself for doing it. That thing is happening again. That thing at the door where I got to say all the things I was never able to before. All of these insane leaps in logic just bound right out of me, so utterly ridiculous that he is rendered speechless.

God, I love rendering him speechless.

‘Did you really just accuse me of having a foot for a hand?’

‘I think “accuse” is a little strong. I have nothing but sympathy for your plight.’

‘There is no plight, you ridiculous creature. My hands and feet are where they are supposed to be, I can assure you.’

‘So the problem is your face.’

‘I see what you are clumsily attempting.’

‘I thought I was attempting it quite well, actually.’

‘Then allow me to disillusion you immediately. Your technique is that of a sixteen-year-old boy fumbling at the underwear of my mind.’

‘I could try harder. Probe more deeply.’

‘You believe I wish to be probed? No, dear me, no, that won’t do at all. See, it is exactly as I predicted: you are in every way unsuitable for this position. I cannot possibly have some snooping reprobate rummaging through my life,’ he says, at which point I know I should be insulted or annoyed. He said I was a teenage boy. He called me clumsy. He thinks I am some criminal who snoops.

Yet somehow all I can think is:

He said ‘reprobate’.

He said ‘disillusion’.

He uses the sorts of words I’ve waited all my life to hear spoken aloud – words I barely know how to pronounce because the only time I’ve ever encountered them has been in books. I had no idea that ‘reprobate’ curled that way, or that ‘disillusion’ sounded so small to begin with and then so big at the end. Though, granted, part of that might be down to the way he talks. His tongue practically makes love to each syllable.

I feel like his sentence should smoke a cigarette, directly after the full stop.

I think I might need to smoke a cigarette, directly after the full stop. Something is sure happening to me. I seem to be sweating just about everywhere and my breaths are coming hard and high, like he is a hill and I just ran up him.

Only that sounds agonising, and this is the opposite.

This is so sweet I would do anything for another taste.

‘Do you think you could say that word again?’

‘You honestly want me to repeat one of the things I just said, despite the fact that most of them were sneering insults?’

‘Are you kidding? The sneering insults were the best parts.’

‘Well, that settles it. I can’t hire you. You are quite mad.’

‘You cannot possibly decide that, based on me enjoying you saying the word “reprobate”. You turned the letter R into Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony. People will probably be playing that letter O at funerals. There is nothing unreasonable about enjoying how the whole thing sounded – not to mention the fact that you said it at all. I mean, who says “reprobate” these days?’ I ask, and again there follows a silence. A big one, that he seems very bitter about once he finally responds. How dare I make him momentarily speechless, I think, and what he says bears that out.

‘People who have read these things called books – you might have heard of them, papery things with lots of squiggles inside,’ he says, and I attempt to hate him here, I really do. I stiffen at the implication, and when I speak my voice is cold.

‘Oh, you mean the things I used to hide under my floorboards so no one would take them away from me?’ I tell him.

But then he goes and says this:

‘Are you suggesting that you had books stolen from you? That these books were somehow forbidden you? By whom? Tell me at once who this monstrous individual is so that I can immediately have them arrested,’ he says.

And I think he actually means it. There isn’t so much as a whiff of facetiousness about his words. He honestly thinks my parents were monstrous, just because they hated me reading. No one has ever thought they were monstrous because they hated me reading. A teacher once shouted at them for forcing me into shoes three sizes too small, and occasionally an official-looking person would come around and write things down about my bruises and the spoiled food and the constant cans of Carling everywhere.

But that was about it, when it came to outrage over their behaviour.

A fact that I then point out to him, in a roundabout way.

‘You can’t have someone arrested for flushing books down a toilet.’

‘Well, that just speaks volumes about our current justice system. If I had my way I would not only arrest this miscreant but have them flogged in the town square,’ he says, and I feel sure he means that too. So much so that the urge to look at him again is suddenly too keen to withstand. I have to take deep breaths just to stop myself doing it.

Then sublimate it into something else.

‘Tell me honestly: did you time-travel here from 1865?’

‘I wish I had. And possessed the means to travel back.’

‘Even though people bathed a lot less then.’

‘I could accept body odour in exchange for a bit of peace.’

‘You think being alive in 1865 would give you peace?’

‘I think at the very least I would fit in more than I do here,’ he says, though I don’t think he means to. At least I don’t think he means to sound so despairing about it. After the words pop out he seems to make a little tutting noise, and it isn’t aimed at me. It’s aimed at himself. He let out some dark hint of who he is, and it irritates him.

It irritates him so much that he immediately tries to get rid of me in what may be the most ludicrous way possible. ‘Well, it was nice meeting you, farewell,’ he says, as though we just finished on a pleasant note and he is now up and shaking my hand.

Despite the fact that we are both still seated.

And he hasn’t asked me a damned thing.

‘But you haven’t even interviewed me yet.’

‘Of course I have – I enquired about your reading habits.’

‘That hardly constitutes an interview.’

‘Very well then, tell me what you would expect of an interview.’

‘You should ask me my name.’

‘Assume that I have.’

‘Molly Parker.’

‘I see. And then…?’ he asks, and here’s the best thing:

I think he genuinely has no idea.

He needs me to tell him.

‘Then you tell me yours.’

‘Why? I’m not interviewing for any position.’

‘So you want me to go around your house calling you something I just made up,’ I suggest, and practically hear him shudder. It almost makes me want to do it anyway – think up ridiculous monikers and have him be disgusted by all of them.

Snooty McBogtrot, I could call him, then I have to suppress a laugh.

Twenty-two years of never having anything to laugh about, and suddenly it overwhelms me to the point where I have to hold it off. I have to use both hands.

‘That sounds like the very worst thing I can imagine. You may call me Mr Harcroft.’

‘Seems rather unfriendly and impersonal.’

‘I think you will find that I am a rather unfriendly and impersonal man. You will also shortly discover that I am singularly exacting, ruthless in my attention to detail and completely without regard for any and all emotional whims. I brook no challenges to my authority and expect to be deferred to without exception when it comes to the precise system I use to govern my household,’ he says, then quite obviously waits for me to be horrified. The problem is, though, that if he is, he will be waiting for ever. I don’t know how to be horrified by all of this. It seems so strange and fantastical that all I can do is marvel at all of it, from the seating arrangements to his furniture right the way through to his every odd word.

He governs his household, I think.

Is it any wonder I say what I then do?

‘So I got the job then?’ I ask.

After which there is a silence so delicious I could grab it in my hands and eat it alive. He honestly thought I would balk at that, I can tell. He even tries to go one better a moment later, with his directions as to what I should do next. ‘You will be sleeping in the attic,’ he says, as though the attic is his version of the top of a terrible tower. He wants to be the evil wizard who has somehow imprisoned a princess.

But he has to know he can never be. My life before was the prison: this is the escape. And it continues to be, no matter what he says or does. ‘Go there directly and remain until your duties begin in the morning,’ he tells me, and the very last thing I feel is fear. I fizz with the idea of finally seeing his face instead. I wonder and wonder about how a man who uses the word ‘miscreant’ will look, and am actually disappointed when I turn and find he has already disappeared.

Though even that soon fades.

There are other delights to uncover – like the pictures on the walls on the way up the narrow staircase, each one creepier than the one before it. I think they might even deserve the label gothic, which sounded so exciting to me when I first read about it that I secretly dyed a net curtain black and wore it as a headdress in the middle of the night. Now I get to live amidst it, in the form of faded photographs of old bearded men who could well be his ancestors.

He has ancestors.

And if that were not exciting enough, there is the room I am supposed to stay in. Does he understand how exciting this room is to me? I imagine he could never do so, since this is his ordinary and everyday life. But to me none of this is ordinary and everyday. The very presence of a brass double bed is enough to place it outside those boundaries. Even the mattress crosses the line, because at home I used to sleep on folded-over towels and two sleeping bags.

Certainly I’ve never had anything like this.

Nor have I had experience of a room that just belongs to me. I have no concept of drawers that I can just stuff with my things – to the point where I can barely fill one of them, and then only because of my two big jumpers. And though the window is more of a skylight, it lets in the dying glow of the day like nothing I’ve ever seen. I stand on the bed just to look through it, and see all of London spread out before me.

I see my life, as it could really be.

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.