Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

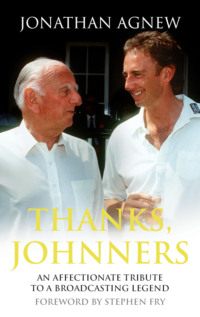

Kitabı oku: «Thanks, Johnners: An Affectionate Tribute to a Broadcasting Legend»

Thanks, Johnners

An Affectionate Tribute to a

Broadcasting Legend

JONATHAN AGNEW

This book is dedicated to my friends and colleagues on Test Match Special, and to our many loyal listeners

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Foreword by Stephen Fry

Introduction

Chapter One - The Guest Speaker

Chapter Two - A Radio Man

Chapter Three - Up to Speed

Photographic Insert 1

Chapter Four - The Leg Over

Chapter Five - ‘What are You Two up to Now?’

Chapter Six - Not Cricket

Photographic Insert 2

Chapter Seven - Noises Off

Chapter Eight - Handing Over

Chapter Nine - The Legacy

Index

About the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

Foreword

by Stephen Fry

Whenever I worry that the growing vulgarity, coarseness, ignorance, roughness, meanness, pessimism, miserabilism and puritanical stupidity of England will get me down, I invent a certain kind of Englishman to put all that right. He is entirely a fantasy figure of course. He must be charming, gallant, funny, courteous, kindly, perceptive, soldierly, honourable and old-fashioned. But old-fashioned in the right way. Not in terms of intolerance, crabbiness or contempt for the new, but in terms of consideration, amiability, attention and open sweetness of nature. Able to walk with kings nor lose the common touch, as Kipling put it. On top of that, this paragon must also, to please me, have a love of laughter, theatre and the world of entertainment. He should, of course, know, understand and venerate cricket.

Impossible that such an ideal could ever exist in the real world; and yet he did, and his name was Brian Alexander Johnston. Gallant? Certainly: the Military Cross is more than just a ‘he turned up and did his bit’ medal; it is an award only ever given for ‘exemplary acts of gallantry’. Johnners won his in 1945 after taking part in the Normandy landings. Naturally, if you ever tried to talk to him about it, he gently glanced the subject to leg. Funny? You don’t need me to remind you of that. I have his ‘Stop it, Aggers!’ moment as a phone ringtone, and I turn to it whenever I feel homesick or unhappy.

The fact is, Brian Johnston was the most perfect and complete Englishmen I ever met. His education at Eton and New College, Oxford, and his commission in the 2nd Battalion, the Grenadier Guards might mark him out in your mind as one of a class who expected to rule and to be respected and obeyed as a matter of course, as a birthright. He had no such pompous expectations. Life was good to him, but it dealt him hardships too. Aggers will take you through those; they tested him as few of us would want to be tested.

I first met him when I was invited to appear on the Radio 4 quiz game Trivia Test Match.

‘Ah, Fryers!’ he cried as I entered the pavilion of the cricket club where the show was to be recorded. ‘Welcome. This is your first time, so perhaps we ought to have a net.’

‘Fryers’? Only he could convincingly abbreviate my name by doubling its letter-count.

Within seconds of meeting him, I felt we were . . . not friends, that would be silly . . . we were the kind of warm acquaintances who would always be glad to see each other again. We spoke of Billy ‘Almost a Gentleman’ Bennett, Sandy Powell, Robb Wilton, George Robey and other music-hall stars, most of whom he had seen many times, and some of whom he knew personally from his old In Town Tonight days. The greatest light came into his eyes when he told tales of the Crazy Gang, his favourites from the golden age of British stage comedy. It was a mystery to many of his TMS listeners as to why he always referred to a Pakistani cricketer called Mansur as ‘Eddie’. Only aficionados of the Crazy Gang would know that the craziest of the gang was always called ‘Monsieur’ Eddie Gray.

To bump into Brian at Lord’s, in the part of London I shall always think of as St Johnners Wood, was the greatest pleasure of a British summer. With him passed something of England we shall never get back.

Introduction

There are many people who have had an impact on my life – while I was growing up, as a professional cricketer, as a journalist and a commentator. But, my father apart, none has been as significant as Brian Johnston.

One of the most natural communicators and broadcasters there has ever been, the man known around the world simply as ‘Johnners’ was a seasoned entertainer on a wide range of programmes on the BBC. He began his career at a time when up to twenty million people would crowd around their radios every Saturday evening. Whether he was spending the night in the Chamber of Horrors at Madame Tussaud’s, lying beneath a railway track as an express train thundered overhead, or gently interviewing a nervous resident of a sleepy village on Down Your Way, Brian Johnston’s decades of broadcasting made him a household name, and every one of his listeners felt as if they knew him, even those who had never met him and were never likely to. But he was best-known as the legendary friendly, welcoming voice of Test Match Special.

Brian was more than merely the presenter of TMS; he was the heartbeat of the programme. He brought to it humour, colour, drama, the ability to establish personal contact with an audience, and, of course, a deep love of cricket that lasted a lifetime; ingredients that made his commentary burst into life in a way that no one had ever quite managed before. Listeners knew, too, that lying just beneath the surface the spirit of a schoolboy was bursting to get out. Be it deliberately waiting until his colleague had stuffed his mouth full of cake before asking him a question on air, or sniggering at even the most contrived double entendre, Johnners was a big kid at heart. And yet, at the age of only ten, he had watched helplessly from a Cornish beach as his father drowned in front of him, while during the Second World War his bravery under enemy fire was such that he was awarded the Military Cross.

Brian was nearly fifty years older than me when I joined Test Match Special in 1991, following in his footsteps as the BBC’s fourth cricket correspondent. We had never met before, but as with many who knew him, something immediately clicked. For someone of my age, Brian was like a kindly old grandfather who the youngsters can quietly tease, but who never loses his temper. Within a few weeks of starting to work together we inadvertently created the notorious broadcasting cock-up now known simply as ‘the Leg Over’, which is still replayed as much today as it was when it first brought much of the nation to a standstill.

Johnners and I will always be linked as a double act because of those ninety seconds of madness, but the impact that living and working alongside him left on me was far greater than the effects of just one giggling fit, however famous it may subsequently have become. I, and many others in commentary boxes around the world, continue to seek to emulate Brian’s relaxed and informal description of cricket, and his ability to make everyone who is either listening or working with him feel welcome.

This book is not a biography of Brian Johnston. The journalist Tim Heald has written the authorised story of Brian’s life, while Brian’s eldest son Barry beautifully recorded every aspect of his father’s full and varied time at the crease in The Life of Brian. I am especially grateful to Barry, and all the Johnston family, for their help and support in the writing of this book.

Thanks, Johnners is a tribute written from the perspective of a man who was fortunate enough to work alongside such a talented and genuinely warm-hearted individual at a key time in his life. Brian Johnston liberated me as a broadcaster, and gave me the confidence to commentate without apprehension or nerves. He showed me how easy and welcoming communication ought to be. Now, in a world governed by brief soundbites, Test Match Special can sometimes seem to stand virtually alone in the broadcast media in allowing conversation, good company and colourful description to flourish in a way that still makes radio intimate in a way that television can never be.

For some who read this book, ‘the Leg Over’ may be their only memory of Brian Johnston. If that is so, well, it is a start at least. But if today’s Test Match Special brings the wonderful game of cricket alive for you, makes you feel involved and, through gentle humour and leg-pulling, puts a smile on your face, then we have succeeded in preserving Johnners’ legacy.

Jonathan Agnew

June 2010

Chapter One

The Guest Speaker

I can remember the first time I heard Test Match Special. I was aged eight or nine, and enjoying another idyllic summer of outdoor life on our farm in Lincolnshire when I became aware of my father carrying a radio around with him. It was not much of a radio, certainly not by the standards of today’s sleek, modern digital models, but was what we would have called a transistor. It was brown in colour and, typical of a farmer’s radio, was somewhat beaten up and splattered with paint. The aerial was always fully extended. Dad would often laugh out loud as he carried it about, the programme echoing loudly around the barns and grain silo as he stored the freshly harvested wheat and barley. It is the perfect summer combination, the smell of the grain and the sound of the cricket, and whenever I think of it the sun always seems to be shining, although that is probably stretching things a bit. When he had finished work for the day, we would play cricket together in the garden, Dad teaching me with tireless patience the basic bowling action. He so wanted me to become an off-spinner like him.

Soon the unmistakable voices became very familiar: Arlott, Johnston, Mosey and the others who with their own different and individual styles helped the summers pass all too quickly with their powerful descriptions and friendly company. The programme sparked an interest in me, in the same way it has in so many tens of thousands of children down the years, igniting a passion that lasts a lifetime. Whether it be playing the game, scoring, watching, umpiring or simply handing down our love of cricket to the next generation, listening to Test Match Special is how most of us got started.

Thanks to that programme, and Brian Johnston’s commentary in particular, I have always associated cricket with fun, banter and friendship. As a boy, if there was cricket being played, I would be following it either on the television or on the radio. Brian was always incredibly cheerful, and it was impossible not to listen with a smile – even if England’s score was really terrible and Geoffrey Boycott had just run somebody out again. Dad’s enjoyment of the humour within the cricket commentary was infectious, and made me appreciate everything that sets Test Match Special apart from other radio sports programmes.

I became rather obsessed with the game, even to the point of blacking out the windows of our sitting room and watching entire Test matches on the television. Until I was ten Brian commentated more on the TV than on the radio, but in 1970, when he was dumped by BBC television with no proper explanation, he moved to radio’s Test Match Special full time. So I joined the legions of cricket nuts who watch the television with the sound turned down and listen to the radio commentary instead. I actually lived the hours of play, with Mum appearing a little wearily with a plate of sandwiches at lunchtime, and some cake at tea. I would not miss a single ball on that black-and-white television, and while my parents recognised how much of a passion I was developing for cricket, I think they felt I needed to get out more. I remember a cousin of mine, Edward, being invited to stay during a Test match. I was furious, and felt this was clearly a plot to get me out of the house and into the fresh air. But Edward sat quietly beside me in the dark for the next five days. By the end, I think he was even starting to like it a little.

At the end of the day’s play it was out into the garden, where I would bowl at a wall for hours on end, trying to repeat what I had seen, and imitating the players, whose styles and mannerisms were etched in my mind. I developed quite a reasonable impersonation of the England captain Ray Illingworth, even down to the tongue sticking out when he bowled one of his off-spinners, and I loved John Snow’s brooding aggression and moodiness. How did Snow bowl so fast from such an ambling run-up? Little could I have imagined that Illingworth would become my first county captain, and that when I moved to journalism Snow would be my travel agent. Then there was the captivating flight and guile of Bishen Bedi, wearing his brightly coloured turbans, and the trundling, almost apologetic run-up of India’s opening bowler, Abid Ali. And Pakistan’s fast bowler Asif Masood, who seemed to start his approach to the wicket by running backwards, and who Brian Johnston famously – and, knowing his penchant for word games and his eye for mischief, almost certainly deliberately – once announced as ‘Massive Arsehood’.

I loved the metronomic accuracy of Derek Underwood, who was utterly lethal bowling on the uncovered pitches of that time, and still have a vivid memory of the moment he bowled out Australia in 1968 – helped, I am sure, by the fact that Johnners was the commentator when the final wicket fell. It was an extraordinary last day of the final Test at The Oval, where a big crowd had gathered in the hope of seeing England secure the win they needed to square the series. A downpour in the early afternoon seemed to put paid to the game, but when it stopped the England captain, Colin Cowdrey, appeared on the field and encouraged the spectators to arm themselves with whatever they could find – towels, mops, blankets and even handkerchiefs – and get to work mopping up the vast puddles of water. On they all came, to the absolute dismay, I imagine, of the Australians, and in contravention of just about every modern-day ‘health and safety’ regulation in existence. Before long, with sawdust scattered everywhere, ‘Deadly Derek’ was in his element. With only three minutes of the Test left, and with all ten England fielders crouching around the bat, he snared the final wicket: the opener John Inverarity, who had been resisting stubbornly from the start of Australia’s innings. Inverarity was facing what was almost certainly the penultimate over, with the number 11, John Gleeson, at the non-striker’s end.

‘He’s out!’ shouted Johnners at the top of his voice. ‘He’s out LBW, and England have won!’

This was my first memory of the great drama and tension that cricket can conjure up, and it came as a result of watching heroes and epic contests on television. This is the reason for my dis appointment that most of today’s children do not have the same opportunity. How can you fall passionately in love with a sport you cannot see?

At Taverham Hall, the prep school just outside Norwich that I attended as a boarder from the age of eight, there was a small television in the room in which you sat while waiting to see matron in the adjoining sick bay. She was a big one for dispensing, twice per day for upset tummies, kaolin and morphine, which tasted utterly disgusting, and then, as a general pick-me-up, some black, sticky, treacly stuff which was equally foul. Despite that, my best pal, Christopher Dockerty, and I would rotate various bogus ailments on a daily basis in order to get a brief look at the cricket on her telly – even just a glimpse of the score was enough. Matron never twigged that Christopher and I were only ever under the weather during a Test match. Incidentally, Chris was a brilliant mimic who could bowl with a perfect imitation of Max Walker’s action while commentating in a more than passable John Arlott. He was also the most desperately homesick little boy in the school. His later life would take an unexpected and ultimately tragic turn. As Major Christopher Dockerty he became one of the most senior and respected counter-terrorism experts in the British Army. Posted to Northern Ireland, he was a passenger on the RAF Chinook helicopter that crashed on the Mull of Kintyre in June 1994, killing all twenty-nine people on board.

My first cricket coach at school was a woman. Eileen Ryder was married to an English teacher, Rowland Ryder, whose father had been the Secretary of Warwickshire County Cricket Club in 1902, when Edgbaston staged its first Test match. The R.V. Ryder Stand, which stood to the right of the pavilion before the recent redevelopments, and where I used to interview the England captain before every Test match there, was named after him. Mrs Ryder was patient and kindly, and along with my father was the person who really taught me how to bowl at a tender age. Like him, she reinforced the image I already had of cricket as a happy and friendly occupation.

A couple of years later we had our first professional coach when Ken Taylor, a former Yorkshire and England batsman, professional footballer and wonderful artist, moved to Norfolk. A gentle and quiet man, he might well have played more than his three Tests had he been more pushy and enjoyed more luck. It has been said that he was an exceptional straight driver because of the narrowness of the ginnells – those little passageways that run between the terraced houses of northern England – in which he batted as a child. I suspect some of the ginnells might even have been cobbled, which would have made survival seriously hard work.

The privileged boys of Taverham Hall, in their caps and blazers of bright blue with yellow trim, must have been quite an eye-opener for Ken. I saw him for the first time in the best part of forty years when Yorkshire CCC held a reunion for its players in 2009, and one of his paintings was auctioned to raise money for the club. It was the most lifelike image one could imagine of Geoffrey Boycott playing an immaculate cover drive. I regret not buying it now, given my close connections to both men. In any case, I managed to encourage Ken onto Test Match Special, and memories of hours spent in the nets with him at Taverham came flooding back.

A trip to London in those days was considered by my dad to be quite an outing, but he booked tickets for the two of us to watch Lancashire play Kent in the 1971 Gillette Cup final at Lord’s. He was still reeling from a disastrous attempt to find Heathrow airport by car at the start of our recent family summer holiday. Utterly lost and desperate, he flagged down a passer-by who kindly offered to take us there, but instead directed us to his house somewhere in London, whereupon he jumped out, leaving us stranded. We opted for the train this time.

The whole occasion had a profound impact on me. The smell and sound of Lord’s was captivating, and it was a good match. I was thrilled by the sight of Peter Lever, the Lancashire fast bowler, tearing in from the Nursery end from what seemed to me an impossibly long run-up. Sitting side-on to the pitch in the old Grandstand, I had never seen a ball travel so fast, and Peter immediately became my childhood hero. The Lancashire captain Jack Bond took a brilliant catch in the covers, and David ‘Bumble’ Lloyd scored 38; these ex-players are all now friends of mine. Dad took his radio, but with an earpiece so I could listen and gaze up at the radio commentary box high to my right in the nearest turret of the Pavilion. All the usual suspects were on duty, and it is surprising to remember now that Brian Johnston, then aged fifty-nine, was only one year away from compulsory retirement as the first BBC cricket correspondent. I suppose I might have wished that one day I would also be commentating from that box, with its wonderful view of the ground. Twenty years later, I would be doing just that.

I moved on to Uppingham School in Rutland in 1973, and one year there was great excitement amongst the boys because Brian Johnston was coming to give a talk. These events usually took place in one of the smaller assembly rooms, which were commonly used for concerts and such things, or in the school theatre. Guest speakers did not normally arouse much excitement among the boys at Uppingham, and those who did come were usually untidily bearded professors and the like. But this was different, and any boys who were not aware of who Brian was, would have been told firmly by their fathers to attend. In the end, such was the demand that Brian addressed us in the vast main hall, which spectacularly dominates the central block of the school’s buildings and which could seat all the pupils and staff – a total of close to nine hundred people. It was almost full. I remember Johnners wearing a grey suit, and standing very tall at a lectern in the middle of the enormous stage. If he had any notes, they can have been little more than a few scribbled jottings. He certainly did not read from a script.

I was sitting about a third of the way down the room, and assumed that Brian would talk purely about cricket, but this was the moment I started to realise that there was more to his life than just cricket commentary. Typically, he was more interested in getting laughs during his well-honed speech than he was in telling us about the more interesting and intimate aspects of his life. That would also be the case when we worked together, because for Johnners everything simply had to be rollicking good fun; almost excessively so. Significant and poignant events in his life, such as the unimaginable horror of watching his father drown off a Cornish beach at the age of ten, or being awarded the Military Cross in the Second World War for recovering casualties under enemy fire, were absolutely never mentioned. Is it possible that his almost overpowering bonhomie, which some people could actually find intimidating rather than welcoming, had been a means of coping with the impact of his father’s sudden and tragic death when Brian was a youngster?

The annual summer trip to Bude was a Johnston family tradition that had been started by Brian’s grandmother, and even extended to their renting the same house every year. The Johnstons were a large family with a very comfortable background as landowners and coffee merchants. Reginald Johnston, Brian’s grandfather, was Governor of the Bank of England between 1909 and 1911, and his father, Charles, had been awarded both the Distinguished Service Order and the Military Cross while serving as a Lieutenant Colonel on the Western Front in the First World War. At the end of the war he returned to the family coffee business, which required him to work long hours in London. As a result Brian, the youngest of four children, saw little of his father, and consequently they did not enjoy a close relationship. Brian’s early childhood was, nonetheless, a happy time, spent on a large farm in Hertfordshire, and with the war over, he and his family had every reason to feel optimistic about the future.

All this was destroyed in the summer of 1922, when the Johnston clan, together with some family friends who were holidaying with them, settled down for a day on the beach at Widemouth Sands in north Cornwall. Ironically, Brian’s father had been due to return to London that morning, but had decided to stay on. At low tide, they all went for a swim. The official version of events is that Brian’s sister Anne was taken out to sea by the notoriously strong current and, seeing that she was in trouble, the Colonel and his cousin, Walter Eyres, swam out to rescue her.

Anne was brought to safety by Eyres, but Brian’s father, who was not a strong swimmer, was clearly struggling as he battled against the tide to reach the shore. A rope was found, and one end was held by the group on the beach while another member of the party, Marcus Scully, took the other end, dived into the water and desperately swam out in an attempt to save Colonel Johnston. But the rope was too short. Scully could not reach the Colonel, who was swept out to sea and drowned at the age of forty-four.

The tragedy was clearly a devastating moment in Brian’s life, and neither he nor his brothers and sister could ever bear to talk about it. To the ten-year-old Brian, his father, a highly decorated army officer, must have been an absolute hero. How can the young boy have felt as he stood helplessly on the shore and watched his father drifting slowly out to sea? A few weeks after the Colonel’s death, his own father – Brian’s grandfather – died from shock.

The whole dreadful saga was made even more complicated by an extraordinary turn of events. Only a year later, Brian’s mother, Pleasance, remarried. Her second husband was none other than Marcus Scully, whose rescue attempt had failed to save Brian’s father. There had been some gossip about the pair having been on more than friendly terms before the Colonel perished. However, it seems more likely that Scully, who was the Colonel’s best friend, suggested that he take on the family in what appeared, to the children at least, to be a marriage of convenience. In the event, it did not last long, and when they divorced Brian’s mother reverted to being called Mrs Johnston.

Interestingly, Brian’s recollection of his father’s death in his autobiography differs from this, the official account, in one crucial respect. As Brian told it, it was Scully who found himself in trouble, not Brian’s sister Anne, and it was a heroic attempt to rescue Scully by the Colonel that cost him his life. This version of events appears to have been a typically charitable act by Brian in order not to distress his sister, who, the family privately agreed, was at fault for ignoring warnings not to swim too far away from the beach, and got into difficulties. Brian could not bring himself to blame her for their father’s death in print, and so concocted a different story for his book.

Brian’s education had started at home with a series of governesses, then at the age of eight he was sent away to boarding school. Temple Grove, located in Eastbourne in Brian’s day, sounds rather an austere establishment, with no electricity or heating. Brian, who was a rather fussy and predictable eater throughout his life, found the food particu -larly awful, and supplemented his diet with Marmite. Years later, I remember him asking Nancy, the much-loved chef whose kitchen was directly below our commentary box in the Pavilion at Lord’s, for a plate of Marmite sandwiches as a change from his usual order of roast beef, which he used to collect from her every lunchtime. Brian appears to have remembered Temple Grove for two reasons: the matron had a club foot, and the headmaster, the Reverend H.W. Waterfield, a glass eye. How did he know he had a glass eye? ‘It came out in conversation!’

Although cricket was Brian’s first love, it seems that he might have been more successful at rugby, in which he was a decent fly-half. He kept wicket for the first XI in his final two years at Temple Grove – he always referred to wicketkeepers as standing ‘behind the timbers’ – and was described in a school report as ‘very efficient’ and unfailingly keen. His batting appears to have been rather eccentric, and he was a notoriously poor judge of a run. This might explain his excitement during commentary on Test Match Special at the prospect of a run-out, and especially at the chaos invariably created by overthrows, which he always referred to as ‘buzzers’. This appears to be very much, although not exclusively, an Etonian expression. Henry Blofeld, like Johnners an Old Etonian, remembers ‘buzzers’ rather than ‘overthrows’ being the term of choice in matches involving the old boys, the Eton Ramblers. Like Johnners, Henry always describes buzzers with particular relish.

From Temple Grove, Brian went on to Eton, which he loved, and remembered as being like a wonderful club. It was there that he discovered he could make people laugh, and also where it is believed he started his unusual habit of making a sound like a hunting horn from the corner of his mouth. We often heard this from the back of the commentary box, usually in the form of two gleeful ‘whoop whoops’ whenever he detected even the faintest whiff of a double entendre in the commentary, or just to amuse himself. ‘It’s amazing,’ Trevor Bailey observed once of an excellent delivery from the Pakistani fast bowler Waqar Younis, ‘how he can whip it out just before tea.’ Rear of commentary box: ‘Whoop whoop!’

As was the case at prep school, cricket was Brian’s particular love at Eton, although he still seemed to be more successful at rugby. He proudly told the story of being surely the only player in the history of the sport to score a try while wearing a mackintosh. This occurred while he was at Oxford. He lost his shorts while being tackled, and had retired to the touchline and put on the coat ‘to cover my confusion’, as he put it. The ball was passed down the three-quarter line and Brian out rageously reappeared on the wing, mackintosh and all, to score between the posts. Oh, to have seen that.

Inevitably, Brian’s dream in his final summer at Eton in 1931 was to represent the first XI and to play against the school’s great rivals, Harrow, in the traditional two-day showpiece at Lord’s. This was almost as much of a date in the calendar of the social elite as it was a cricket match, and it was the ambition of every cricketer at both schools to make the cut. But Brian never did, and as would be the case with his sacking from the BBC television commentary team many years later, he deeply resented the fact, and often spoke quite openly about it. He laid the blame firmly at the feet of one Anthony Baerlein, who had kept wicket for the Eton first XI for the previous two years. Brian always held the firm belief that Baerlein should have left school at the end of the summer term, allowing Brian a free run at his place behind the timbers in his final year. But according to Brian, Baerlein, with an eye on a third appearance at Lord’s, decided to stay on an extra year, and dashed Brian’s hopes. (Records show that Baerlein was indeed nineteen and a half years old when he, rather than Johnners, played against Harrow in the summer of 1931, but also that he had arrived at Eton in 1925, and was therefore in the same year as Brian. He would go on to become a novelist and journalist before joining the RAF in the Second World War. He was killed in action in October 1941, at the age of just twenty-nine.)

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.