Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

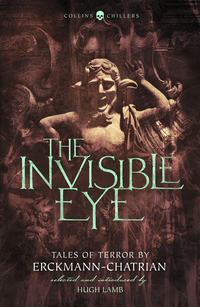

Kitabı oku: «The Invisible Eye: Tales of Terror by Emile Erckmann and Louis Alexandre Chatrian», sayfa 2

By what strange intuition did she suspect anything? I know not; but I gently lowered the uplifted slate into its place, and gave over watching for the rest of that day.

The day following Fledermausse appeared to be reassured. A jagged ray of light fell into the gallery; passing this, she caught a fly, and delicately presented it to a spider established in an angle of the roof.

The spider was so large, that, in spite of the distance, I saw it descend then, gliding along one thread, like a drop of venom, seize its prey from the fingers of the dreadful old woman, and remount rapidly. Fledermausse watched it attentively; then her eyes half-closed, she sneezed, and cried to herself in a jocular tone: ‘Bless you, beauty! – bless you!’

For six weeks I could discover nothing as to the power of Fledermausse: sometimes I saw her peeling potatoes, sometimes spreading her linen on the balustrade. Sometimes I saw her spin; but she never sang, as old women usually do, their quivering voices going so well with the humming of the spinning-wheel. Silence reigned about her. She had no cat – the favourite company of old maids; not a sparrow ever flew down to her yard, in passing over which the pigeons seemed to hurry their flight. It seemed as if everything were afraid of her look.

The spider alone took pleasure in her society.

I now look back with wonder at my patience during those long hours of observation; nothing escaped my attention, nothing was indifferent to me; at the least sound I lifted my slate. Mine was a boundless curiosity stimulated by an indefinable fear.

Toubec complained.

‘What the devil are you doing with your time, Master Christian?’ he would say to me. ‘Formerly, you had something ready for me every week; now, hardly once a month. Oh, you painters! As soon as they have a few kreutzer before them, they put their hands in their pockets and go to sleep!’

I myself was beginning to lose courage. With all my watching and spying, I had discovered nothing extraordinary. I was inclining to think that the old woman might not be so dangerous after all – that I had been wrong, perhaps, to suspect her. In short, I tried to find excuses for her. But one fine evening, while, with my eye to the opening in the roof, I was giving myself up to these charitable reflections, the scene abruptly changed.

Fledermausse passed along her gallery with the swiftness of a flash of light. She was no longer herself: she was erect, her jaws knit, her look fixed, her neck extended; she moved with long strides, her grey hair streaming behind her.

‘Oh, oh!’ I said to myself, ‘something is going on!’

But the shadows of night descended on the big house, the noises of the town died out, and all became silent. I was about to seek my bed, when, happening to look out of my skylight, I saw a light in the window of the green chamber of the Boeuf-gras – a traveller was occupying that terrible room!

All my fears were instantly revived. The old woman’s excitement explained itself – she scented another victim!

I could not sleep at all that night. The rustling of the straw of my mattress, the nibbling of a mouse under the floor, sent a chill through me. I rose and looked out of my window – I listened. The light I had seen was no longer visible in the green chamber.

During one of these moments of poignant anxiety – whether the result of illusion or reality – I fancied I could discern the figure of the old witch, likewise watching and listening.

The night passed, the dawn showed grey against my window-panes, and, slowly increasing, the sounds and movements of the re-awakened town arose. Harassed with fatigue and emotion, I at last fell asleep; but my repose was of short duration, and by eight o’clock I was again at my post of observation.

It appeared that Fledermausse had passed a night no less stormy than mine had been; for, when she opened the door of the gallery, I saw that a livid pallor was upon her cheeks and skinny neck. She had nothing on but her chemise and a flannel petticoat; a few locks of rusty grey hair fell upon her shoulders. She looked up musingly towards my garret; but she saw nothing – she was thinking of something else.

Suddenly she descended into the yard, leaving her shoes at the top of the stairs. Doubtless her object was to assure herself that the outer door was securely fastened. She then hurried up the stairs, three or four at a time. It was frightful to see! She rushed into one of the side rooms, and I heard the sound of a heavy box-lid fall. Then Fledermausse reappeared in the gallery, dragging with her a life-size dummy – and this figure was dressed like the unfortunate student of Heidelberg!

With surprising dexterity the old woman suspended this hideous object to a beam of the over-hanging roof, then went down into the yard to contemplate it from that point of view. A peal of grating laughter broke from her lips – she hurried up the stairs, and rushed down again, like a maniac; and every time she did this she burst into fresh fits of laughter.

A sound was heard outside the street door, the old woman sprang to the dummy, snatched it from its fastening, and carried it into the house; then she reappeared and leaned over the balcony, with outstretched neck, glittering eyes, and eagerly listening ears. The sound passed away – the muscles of her face relaxed, she drew a long breath. The passing of a vehicle had alarmed the old witch.

She then, once more, went back into her chamber, and I heard the lid of the box close heavily.

This strange scene utterly confounded all my ideas. What could that dummy mean?

I became more watchful and attentive than ever. Fledermausse went out with her basket, and I watched her to the top of the street; she had resumed her air of tottering age, walking with short steps, and from time to time half-turning her head, so as to enable herself to look behind out of the corners of her eyes. For five long hours she remained abroad, while I went and came from my spying-place incessantly, meditating all the while – the sun heating the slates above my head till my brain was almost scorched.

I saw at his window the traveller who occupied the green chamber at the Boeuf-gras; he was a peasant of Nassau, wearing a three-cornered hat, a scarlet waistcoat, and having a broad laughing countenance. He was tranquilly smoking his pipe, unsuspicious of anything wrong.

About two o’clock Fledermausse came back. The sound of her door opening echoed to the end of the passage. Presently she appeared alone, quite alone in the yard, and seated herself on the lowest step of the gallery-stairs. She placed her basket at her feet and drew from it, first several bunches of herbs, then some vegetables – then a three-cornered hat, a scarlet velvet waistcoat, a pair of plush breeches, and a pair of thick worsted stockings – the complete costume of a peasant of Nassau!

I reeled with giddiness – flames passed before my eyes.

I remembered those precipices that drew one towards them with irresistible power – wells that have had to be filled up because of persons throwing themselves into them – trees that have had to be cut down because of people hanging themselves upon them – the contagion of suicide and theft and murder, which at various times has taken possession of people’s minds, by means well understood; that strange inducement, which makes people kill themselves because others kill themselves. My hair rose upon my head with horror!

But how could this Fledermausse – a creature so mean and wretched – have made discovery of so profound a law of nature? How had she found the means of turning it to the use of her sanguinary instincts? This I could neither understand nor imagine. Without more reflection, however, I resolved to turn the fatal law against her, and by its power to drag her into her own snare. So many innocent victims called for vengeance!

I hurried to all the old clothes-dealers in Nuremberg; and by the evening I arrived at the Boeuf-gras, with an enormous parcel under my arm.

Nikel Schmidt had long known me. I had painted the portrait of his wife, a fat and comely dame.

‘Master Christian!’ he cried, shaking me by the hand, ‘to what happy circumstance do I owe the pleasure of this visit?’

‘My dear Mr Schmidt, I feel a very strong desire to pass the night in that room of yours up yonder.’

We were on the doorstep of the inn, and I pointed up to the green chamber. The good fellow looked suspiciously at me.

‘Oh! don’t be afraid,’ I said, ‘I’ve no desire to hang myself.’

‘I’m glad of it! I’m glad of it! for frankly, I should be sorry – an artist of your talent. When do you want the room, Master Christian?’

‘Tonight.’

‘That’s impossible – it’s occupied.’

‘The gentleman can have it at once, if he likes,’ said a voice behind us; ‘I shan’t stay in it.’

We turned in surprise. It was the peasant of Nassau; his large three-cornered hat pressed down upon the back of his neck, and his bundle at the end of his travelling-stick. He had learned the story of the three travellers who had hung themselves.

‘Such chambers!’ he cried, stammering with terror; ‘it’s – it’s murdering people to put them into such! – you – you deserve to be sent to the galleys!’

‘Come, come calm yourself,’ said the landlord; ‘you slept there comfortably enough last night.’

‘Thank Heaven! I said my prayers before going to rest, or where should I be now?’

And he hurried away, raising his hands to heaven.

‘Well,’ said Master Schmidt, stupefied, ‘the chamber is empty, but don’t go into it to do me an ill turn.’

‘I might be doing myself a much worse one,’ I replied.

Giving my parcel to the servant-girl, I went and seated myself among the guests who were drinking and smoking.

For a long time I had not felt more calm, more happy to be in the world. After so much anxiety, I saw approaching my end – the horizon seemed to grow lighter. I know not by what formidable power I was being led on. I lit my pipe, and with my elbow on the table and a jug of wine before me, and sometimes rousing myself to look at the woman’s house, I seriously asked myself whether all that had happened to me was more than a dream. But when the watchman came, to request us to vacate the room, graver thoughts took possession of my mind, and I followed, in meditative mood, the little servant-girl who preceded me with a candle in her hand.

III

We mounted the window flight of stairs to the third storey; arrived there, she placed the candle in my hand, and pointed to a door.

‘That’s it,’ she said, and hurried back down the stairs as fast as she could go.

I opened the door. The green chamber was like all other inn bedchambers; the ceiling was low, the bed was high. After casting a glance round the room, I stepped across to the window.

Nothing was yet noticeable in Fledermausse’s house, with the exception of a light, which shone at the back of a deep obscure bedchamber – a nightlight, doubtless.

‘So much the better,’ I said to myself, as I re-closed the window-curtains; ‘I shall have plenty of time.’

I opened my parcel, and from its contents put on a woman’s cap with a broad frilled border; then, with a piece of pointed charcoal, in front of the glass, I marked my forehead with a number of wrinkles. This took me a full hour to do; but after I had put on a gown and a large shawl, I was afraid of myself; Fledermausse herself was looking at me from the depths of the glass!

At that moment the watchman announced the hour of eleven. I rapidly dressed the dummy I had brought with me like the one prepared by the old witch. I then drew apart the window-curtains.

Certainly, after all I had seen of the old woman – her infernal cunning, her prudence, and her address – nothing ought to have surprised even me; yet I was positively terrified.

The light, which I had observed at the back of her room, now cast its yellow rays on her dummy, dressed like the peasant of Nassau, which sat huddled up on the side of the bed, its head dropped upon its chest, the large three-cornered hat drawn down over its features, its arms pendant by its sides, and its whole attitude that of a person plunged in despair.

Managed with diabolical art, the shadow permitted only a general view of the figure, the red waistcoat and its six rounded buttons alone caught the light; but the silence of night, the complete immobility of the figure, and its air of terrible dejection, all served to impress the beholder with irresistible force; even I myself, though not in the least taken by surprise, felt chilled to the marrow of my bones. How, then, would a poor countryman taken completely off his guard have felt? He would have been utterly overthrown; he would have lost all control of will, and the spirit of imitation would have done the rest.

Scarcely had I drawn aside the curtains than I discovered Fledermausse on the watch behind her window-panes.

She could not see me. I opened the window softly, the window over the way softly opened too; then the dummy appeared to rise slowly and advance towards me; I did the same, and seizing my candle with one hand, with the other threw the casement wide open.

The old woman and I were face to face; for, overwhelmed with astonishment, she had let the dummy fall from her hands. Our two looks crossed with an equal terror.

She stretched forth a finger, I did the same; her lips moved, I moved mine; she heaved a deep sigh and leant upon an elbow. I rested in the same way.

How frightful the enacting of this scene was I cannot describe; it was made up of delirium, bewilderment, madness. It was a struggle between two wills, two intelligences, two souls, one of which sought to crush the other; and in this struggle I had the advantage. The dead were on my side.

After having for some seconds imitated all the movements of Fledermausse, I drew a cord from the folds of my petticoat and tied it to the iron stanchion of the signboard.

The old woman watched me with open mouth. I passed the cord round my neck. Her tawny eyeballs glittered; her features became convulsed.

‘No, no!’ she cried, in a hissing tone; ‘no!’

I proceeded with the impassibility of a hangman.

Then Fledermausse was seized with rage.

‘You’re mad! you’re mad!’ she cried, springing up and clutching wildly at the sill of the window; ‘you’re mad!’

I gave her no time to continue. Suddenly blowing out my light, I stooped like a man preparing to make a vigorous spring, then seizing my dummy slipped the cord about its neck and hurled it into the air.

A terrible shriek resounded through the street; then all was silent again.

Perspiration bathed my forehead. I listened a long time. At the end of an hour I heard far off – very far off – the cry of the watchman, announcing that midnight had struck.

‘Justice is at last done,’ I murmured to myself; ‘the three victims are avenged. Heaven forgive me!’

I saw the old witch, drawn by the likeness of herself, a cord about her neck, hanging from the iron stanchion projecting from her house. I saw the thrill of death run through her limbs and the moon, calm and silent, rose above the edge of the roof, and shed its cold pale rays upon her dishevelled head.

As I had seen the poor young student of Heidelberg, I now saw Fledermausse.

The next day all Nuremberg knew that ‘the Bat’ had hung herself. It was the last event of the kind in the Rue des Minnesängers.

THE OWL’S EAR

On a warm evening in July 1835, Kasper Boeck, a shepherd of the small village of Hirchwiller, presented himself before the burgomaster, Pétrus Mauerer, who had just finished his supper and was having a glass of Kirsch to help his digestion.

The burgomaster, tall and wiry, with his upper lip covered with a huge grey moustache, had in days gone by served in the armies of the arch-duke Charles. His was a bantering disposition, he had the village under his thumb, it was said, and ruled it with a rod of iron.

‘Mr Burgomaster!’ exclaimed the shepherd.

But Pétrus Mauerer, without waiting for the end of his speech, frowned and said to him: ‘Kasper Boeck, start by removing your hat, remove your dog from the room, and then speak clearly, intelligibly, without stammering, so that I can understand you.’

Kasper took out his dog and returned with his hat off.

‘Ah well!’ said Pétrus, seeing him silent. ‘What’s going on?’

‘What’s going on is that the “ghost” has appeared again in the ruins of Geierstein!’

‘Ah! I suspected it. Did you get a good look at it?’

‘Very good, Mr Burgomaster.’

‘Without shutting your eyes?’

‘Yes, Mr Burgomaster. I had my eyes wide open. It was a fine moonlit night.’

‘What shape did it have?’

‘That of a small man.’

‘Good!’ And turning towards a glass door on his left, ‘Katel!’ the burgomaster shouted.

An old female servant half-opened the door.

‘Sir?’

‘I am going to take a walk on the hill. You will wait for me till ten o’clock. Here is the key.’

‘Yes, master.’

Then the old soldier took down a gun from above the door, checked its priming, and slung it across his shoulder; then addressing Kasper Boeck: ‘You will alert the constable to meet me in the small holly bush lane behind the mill,’ he said. ‘Your “ghost” must be some marauder … but if it turns out to be a fox, I will have myself a magnificent hat with long flaps made of it.’

Mauerer and the humble Kasper went out. The weather was splendid, the stars clear and innumerable. While the shepherd went and knocked at the constable’s door, the burgomaster disappeared up a small lane of alder trees, which wound its way behind the old church. Two minutes later Kasper and the constable Hans Goerner, a pistol at his hip, ran to join Master Pétrus in the holly-lined lane. The three of them proceeded together to the ruins of Geierstein.

These ruins, situated some twenty minutes from the village, seemed quite insignificant; they were some pieces of dilapidated walls, four to six feet high, which stretched out in the midst of the heather. Archaeologists call them the aqueducts of Seranus, the Roman camp of the Holderlock, or the remains of Théodoric, according to their whim. The only thing which was really remarkable in these ruins was the stairway of a chamber hewn from the rock.

In a manner contrary to spiral stairs, instead of concentric circles narrowing at each step, the spiral of this one got wider, so that the bottom of the cistern was three times wider than the entrance. Was it a whim of architecture, or rather some other reason which gave rise to this bizarre structure? Little does it matter! The fact is that there resulted from it in the cistern this vague roaring such as can be heard by pressing a seashell to one’s ear, and that one can hear the steps of the travellers on the gravel, the stirring of the air, the rustling of the leaves, and even the distant words of those passing along at the foot of the hill.

And so our three characters climbed the little path, between the vines and the kitchen-gardens of Hirchwiller.

‘I can see nothing,’ said the burgomaster, raising his nose mockingly.

‘Nor I,’ repeated the constable, imitating the tone of the other.

‘It is in the hole,’ murmured the shepherd.

‘We shall see, we shall see,’ took up the burgomaster.

Thus it was that after a quarter of an hour they arrived at the entrance to the chamber. The night was bright, clear, and perfectly calm. As far as the eye could see the moon outlined nocturnal landscapes of bluish lines, studded with slender trees, whose shadows seem sketched in black pencil. The heather and the broom in blossom perfumed the air with their sharp smell and the frogs of a neighbouring pool sang their full-throated chorus, interrupted with silences. But all these details escaped our fine countrymen. Their sole thoughts were of catching the ‘spirit’.

When they reached the stair, all three stopped and listened, then looked into the darkness. Nothing appeared, nothing stirred.

‘Confound it,’ said the burgomaster. ‘We have forgotten to bring a candle. You go down, Kasper, you know the way better than me. I’ll follow.’

At this suggestion the shepherd stepped back suddenly. If left to his own devices the poor man would have taken flight. His woeful countenance made the burgomaster burst out laughing.

‘Ah well, Hans, since he doesn’t want to go down, you show me the way,’ he said to the constable.

‘But, master burgomaster,’ said the latter, ‘you are well aware that there are steps missing. We would risk breaking our necks!’

‘Well then, what are we to do?’

‘Yes, what are we to do?’

‘Send your dog,’ resumed Pétrus.

The shepherd whistled for his dog, showed him the stairs, urged him down; but he was no more willing than the rest to try his luck.

At that moment a bright idea struck the constable.

‘Hey, Mr Burgomaster,’ he said. ‘If you were to fire a shot into it …’

‘Indeed,’ exclaimed the other, ‘you are right. One will see clearly, at least.’

And without hesitation the good fellow approached the stair, levelling his gun.

But because of the acoustic effect described earlier, the ‘spirit’, the marauder, the individual, who was actually in the chamber, had heard everything. The idea of being shot at didn’t appeal to him, for in a piercing, high-pitched voice he shouted out: ‘Stop! Don’t shoot! I’m coming up!’

Then the three dignitaries looked at each other, chuckling, and the burgomaster, leaning forward again into the opening, exclaimed in a coarse voice: ‘Hurry up, you rogue, or I’ll shoot! Hurry up!’

He cocked his gun. The click appeared to hasten the ascent of the mysterious character. Stones could be heard rolling. However it took another minute before he appeared, the chamber being over sixty feet deep.

What was this man doing in the midst of such darkness? He must be some great criminal! Thus at least thought Pétrus Mauerer and his assistants.

At last a vague shape emerged from the shadow, then slowly a small man, four and a half feet tall at the most, thin, in rags, his face wizened and yellow, his eyes sparkling like those of a magpie and his hair untidy, came out shouting: ‘What right have you to come and trouble my studies, you wretches?’

This grandiloquence hardly matched his clothes and his appearance, so the indignant burgomaster replied: ‘Try and show some respect, you rogue, or I’ll start by giving you a thrashing.’

‘A thrashing!’ said the little man, hopping with anger and standing right under the burgomaster’s nose.

‘Yes,’ resumed the former, who couldn’t help but admire the courage of the pygmy, ‘if you don’t answer satisfactorily the questions that I am going to put to you. I am the burgomaster of Hirchwiller, here is the village constable and the shepherd with his dog. We are stronger than you … be sensible and tell me who you are, what you are doing here, and why you don’t dare appear in broad daylight. Then we can see what shall be done with you.’

‘All that’s none of your business,’ answered the little man in his curt voice. ‘I shall not answer you.’

‘In that case, march,’ said the burgomaster, grasping him by the nape of the neck. ‘You’ll spend the night in prison.’

The little man struggled but in vain. Completely exhausted, he said (not without some nobility), ‘Let me go, sir. I yield to force. I shall follow you.’

The burgomaster, who wasn’t lacking in manners himself, became calmer in his turn.

‘Your word?’ he said.

‘My word!’

‘Fine … Quick march!’

And that is how on the night of 29 July 1835 the burgomaster captured a small red-haired man, as he emerged from the cave of Geierstein.

On their return to Hirchwiller, the vagabond was double-locked in, not forgetting the outside bolt and the padlock. Afterwards everyone went to recover from their exertions. Pétrus Mauerer, once in bed, pondered over this strange adventure till midnight.

The next day, about nine o’clock, Hans Goerner, the constable, having received orders to bring the prisoner to the town-hall, so that he could undergo a new examination, went with four sturdy lads to the cell. They opened the door, quite curious to look at the will-o’-the-wisp. They saw him hanging by his tie from the bars of the skylight. Several say that he was still kicking … others that he was already stiff. Whichever it was, someone ran off to get Pétrus Mauerer, to inform him of the fact. What is certain is that at the arrival of the latter, the little man had breathed his last.

The magistrate and the doctor of Hirchwiller drew up a formal report of the catastrophe. The unknown man was buried and all was settled.

Now about three weeks after these events, I went to see my cousin Pétrus Mauerer. I am his closest relative and, consequently, his heir. This circumstance maintains an intimate relationship between us. We were dining together, chatting of this and that, when the burgomaster told me the little story as I have just related it.

‘It’s strange, cousin,’ I said to him, ‘really strange. And you have no other information on this unknown man?’

‘None.’

‘Have you found anything that could put you on the track of his intentions?’

‘Absolutely nothing, Christian.’

‘But after all, what could he have been doing in the chamber? What was he living on?’

The burgomaster shrugged his shoulders, filled our glasses, and answered me: ‘Your health, cousin.’

‘And yours.’

We remained silent for some moments. It was impossible for me to accept the sudden end of the adventure. In spite of myself I gloomily pondered over the sad fate of certain men who appear and disappear in this world, like the grass in the fields, without leaving the slightest memory or the slightest regret.

‘Cousin,’ I resumed, ‘how long would it take from here to the ruins of Geierstein?’

‘Twenty minutes at the most. Why?’

‘Because I would like to see them.’

‘You know that today we have a meeting of the town council and I cannot accompany you.’

‘Oh! I shall be able to find them on my own.’

‘No, the constable shall show you the way, he has nothing better to do.’ My dear cousin called his servant.

‘Katel, get Hans Goerner … make him hurry up … It’s two o’clock. I must go.’

The servant went out and the constable wasn’t long in coming. He received orders to guide me to the ruins.

While the burgomaster was making his way solemnly to the council chamber, we were already going up the hill. Hans Goerner pointed out the remains of the aqueduct. At this point the rocky ridges of the plateau, the bluish distances of the Hundsrück, the dismal dilapidated walls, covered in a dark ivy, the tolling of the bell of Hirchwiller, summoning the dignitaries to the meeting, the constable panting, clinging to the brushwood … took on in my eyes a sad, harsh hue. It was the story of this poor hanged man which stained the horizon.

The stairway to the chamber appeared very strange, its spiral elegant. The prickly bushes in the clefts of each step, the deserted appearance of the surroundings, all were in harmony with my sadness. We descended. Soon the bright point of the opening which seemed to grow narrower and narrower and to assume the form of a star with curved rays, alone sent us its pale light.

When we reached the bottom of the chamber what a superb view awaited us of those stairs lit up underneath, throwing their shadows with wonderful regularity. Then I heard the buzzing which Pétrus had told me about; the huge granite conch had as many echoes as stones!

‘Since the little man, has anyone come down here?’ I asked the constable.

‘No, sir. The peasants are afraid. They think that the hanged man will return.’

‘And you?’

‘Me, I’m not curious.’

‘But the magistrate … his duty was …’

‘Humph! What would he be doing in the “Owl’s Ear”?’

‘They call this the Owl’s Ear?’

‘Yes.’

‘It is almost that,’ I said, looking up. ‘This inverted vault forms the outer ear very well, the underneath part of the steps represents the drum, and the bends of the stairway the cochlea, the labyrinth and the opening of the ear. That then explains the murmuring that we can hear: we are at the bottom of a colossal ear.’

‘That is very possible,’ said Hans Goerner, who seemed to understand nothing of my observations.

We were on our way back up. I had already taken the first steps when I felt something snap beneath my foot. I bent down to see what it could be and I noticed at the same time a white object in front of me. It was a sheet of torn paper. As for the hard matter that had been pulverized, I recognized a sort of pot made of glazed stoneware.

‘Ho! Ho!’ I said to myself, ‘this will be able to throw some light on the burgomaster’s story for us.’

And I joined Hans Goerner, who was by now waiting for me at the kerb of the cistern.

‘Now, sir,’ he shouted to me, ‘where would you like to go?’

‘First of all let us sit down a little, we shall see presently.’

And I found a place on a large stone, while the constable let his hawk-like eyes gaze all around the village, to discover marauders in the gardens, if there were any.

I carefully examined the stoneware vessel, of which no more than a fragment remained. This fragment took the shape of a funnel, lined with down on the inside. It was impossible for me to make out its purpose. Next I read the piece of paper, which was written on in a very steady hand. I transcribe it here according to the text. It seems to be a continuation of another sheet, for which I have since searched in the vicinity of the ruin, but in vain.

My ‘microeartrumpet’ has therefore the double advantage of multiplying ad infinitum the intensity of sounds, and of being able to fit the ear, which in no way impedes the observer. You cannot imagine, my dear master, the charm that one feels on hearing these thousands of imperceptible sounds which, on fine summer days, blend into one mighty buzzing. The bee has his song like the nightingale, the wasp is the warbler of the mosses, the cicada is the lark of the tall grasses, in this the mite is the wren – it has only a sigh, but this sigh is melodious!

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.