Kitabı oku: «Bowland Beth: The Life of an English Hen Harrier»

COPYRIGHT

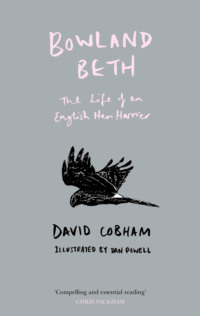

William Collins An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF WilliamCollinsBooks.com This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2017 Copyright © David Cobham 2017 Illustrations (including cover artwork) by Dan Powell David Cobham asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins. Source ISBN: 9780008251895 Ebook Edition © August 2017 ISBN: 9780008251925 Version: 2017-07-11

William Collins An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF WilliamCollinsBooks.com This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2017 Copyright © David Cobham 2017 Illustrations (including cover artwork) by Dan Powell David Cobham asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins. Source ISBN: 9780008251895 Ebook Edition © August 2017 ISBN: 9780008251925 Version: 2017-07-11

For Stephen Murphy,

who guards the flame that

keeps alive the future of our

English hen harriers.

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Prologue

Bowland Beth

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Epilogue

Acknowledgements

Index

About the Publisher

Bowland Beth, named after the Forest of Bowland where she was bred, was an exceptional hen harrier. Some harriers, when near to fledging, stand head and shoulders above the rest of the brood. They are bigger, their plumage is glossier and richer in colour, their eyes are brighter and they fledge ahead of their siblings. Beth was one such.

Following the style of Henry Williamson’s Tarka the Otter and Fred Bodsworth’s Last of the Curlews, I have dramatised Beth’s short life between 2011 and 2012, trying to enter her world to show what being a hen harrier today is like. I have immersed myself not only in the day-to-day regimen of her life – the hours of hunting, bathing, keeping her plumage in order and roosting – but have also attempted to express the fear of living in an environment managed to provide packs and packs of driven grouse for a few wealthy people to shoot for sport.

I hope that by dramatising Bowland Beth’s life I can rally another group of conservationists to join other groups already working hard to challenge those who are determined to illegally exterminate English hen harriers in the interests of driven grouse shooting.

Nearly fifty years ago I made a film of Tarka the Otter, and when it was finished we held a special press show for children, mostly teenagers. Afterwards I asked the audience to come forward and ask questions. Mostly they wanted to know how we made the bubbles and blood in the river. Finally, I was left with one teenaged girl standing before me. When I asked her whether she had liked the film, she said: ‘The otter died. It made me cry.’ To her astonishment I replied: ‘That’s wonderful. You felt something.’

I’m often told that my film of Tarka played an important role in getting otter hunting banned in England and Wales in 1980. Can this dramatised version of Beth’s life awaken similar emotions in people’s hearts and compel them to stand up and deplore in the strongest terms the illegal persecution of the few remaining breeding hen harriers in England? I hope so.

I have been able to dramatise Beth’s life because she was fitted with a satellite tag, and the moment she fledged she was tracked as she sped off to a grouse moor at Nidderdale thirty miles away. A select few watched with delight and alarm as she foraged over a wider and wider area. She survived the winter, and in late spring her hormones kicked in and she started searching high and low for a mate. Her journeys up into the wilds of Scotland made her a national celebrity. On one journey north she covered 125 miles in just eight and a half hours, but without fail she returned to where she had been fledged in the Forest of Bowland.

I knew about the Forest of Bowland because my wife Liza had visited it whenever she could when she was performing in plays at the Grand Theatre in Blackpool. Each time she came back she was bubbling over at the number of harriers she had seen and how kind Stephen Murphy, Natural England’s hen harrier project officer in Bowland, had been in showing her round.

Now, on 24 May 2012, I was going to see Bowland myself. I was researching for a book I was writing on the state of our birds of prey in Britain today and my companion was Eddie Anderson, whom I had known for nearly fifty years. When I first met him he was a gamekeeper. Eventually, after seven years, he gave up gamekeeping and forged a fine career making programmes for Anglia TV and BBC East.

We travelled by train from Norfolk. At Clitheroe, our destination, we were met by the late Mick Carroll, one of Stephen Murphy’s most dependable hen harrier watchers. He was going to drive us around Bowland, so we got into his car and he whisked us off to The Hark to Bounty pub in Slaidburn, where we were booked in for two nights.

We had a brief meeting with Stephen Murphy after breakfast. He promised to show us around the following day and then handed us over to Bill Hesketh and Bill Murphy, Stephen’s local, highly regarded harrier watchers. The rain had cleared, and the fells and moorland sparkled like a newly minted coin.

The rolling hills were dominated by a patchwork of green sprouting heather set against lower areas of grass split up into tiny fields by fences and stone walls, and I could quite understand why the place had been named an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty, a European designation that recognises the importance of its heather moorland and blanket bog as a special habitat for upland birds.

The wild, desolate landscape is an excellent location for bird watching. Curlew, golden plover, oystercatchers and snipe are all found here, and migrating dotterel pass through in spring and autumn. The summer population of breeding curlew is one of the most buoyant in England, and short-eared owls can regularly be seen hunting in daylight for their favourite prey, short-tailed field voles.

Three important birds of prey breed in the Forest of Bowland: the merlin, our smallest bird of prey and not much bigger than a mistle thrush, the much larger peregrine falcon, which, with its 200 mph scything stoop, has been described as the most successful bird in the world, and the hen harrier. The hen harrier is the symbol of the Forest of Bowland and used to be seen regularly as it floated low over moorland hunting for small birds and field voles.

March 2011. Late in the afternoon at the beginning of March, a dark chocolate-brown female hen harrier wheeled over the Forest of Bowland. The low sun enhanced her brilliant orange eyes, deep set in her owl-like face. She was looking down on the moors, still in the grip of last night’s frost. Lines of grouse butts, positioned at the end of each drive, threw long shadows across the heather. A quick flick of a tail feather and a stronger down-beat on one wing brought her facing north. Below, she could pick out Ward’s Stone, the highest point in the Forest. Beyond, in the far distance, her eyes, eight times sharper than ours, picked out the Wig Stones thirty miles to the north. She was hungry. Her only kill had been a meadow pipit, not much of a meal. Where were the other harriers hunting?

She turned, flying across the Roman road towards the source of the Whitendale River. At once she spotted two harriers hunting the boggy ground draining into the river, so she spread her tail to check her speed, half closed her wings and in a series of zig-zags, the air whispering through her primaries, dropped down to join them.

Selecting an area to hunt over, she flew downwind, letting the wind do all the work, her wings held in a ‘V’ above her back. She scanned the hoarfrost-rimed rushes and Molinia grasses passing slowly beneath her for any sign of movement, then turned at a dry stone wall and flew upwind. Flap, flap, flap, glide. She quartered up and down the marshy area like a person searching for something they had lost, but she was hungry and needed to make a kill.

She saw little piles of cut grasses piled on the banks of a rivulet – signs of water voles, snug and warm in their burrows. She flapped her wings, spread her tail and slowed down. Ahead was a muddy patch that was untouched by the overnight frost. The cryptic plumage of a common snipe blended with the zig-zag pattern of the short grasses in the background, and it was only the sudden movement as the snipe plunged its sensitive bill into the mud that gave it away. The harrier suddenly flapped her wings once, stretched her legs down in line with her targeting eye and plunged down, her needle-sharp talons crushing the life out of the snipe.

She carried her kill away to a dense clump of rushes where she could pluck it and feed undisturbed. Ten minutes later, hunger satisfied, she joined the other harriers that were making their way back to the communal roost site at Brackenholes Clough.

The story of Bowland Beth is indelibly linked to Stephen Murphy, who leads the Natural England mission to safeguard the few remaining hen harriers in Bowland. I have known Stephen since 2006, when he radio-tagged a pair of marsh harrier chicks at the Hawk and Owl Trust reserve at Sculthorpe Moor in Norfolk. With the help of my original interviews with him in 2012 – and many recorded over the years 2014 to 2016 – I have been able to piece together the events that ushered Bowland Beth into the world.

I am looking at a photograph of him as I write. He has close-cropped hair, fine-chiselled features and is grinning at the camera because he is holding a month-old hen harrier chick on his knee. He radiates a natural enthusiasm for hen harriers, infecting everyone he meets with his love for these birds.

‘My dream job at Bowland, which I started in 2002, was seen, by some, as a poisoned chalice,’ he says. ‘Bowland is a place I love dearly. It had once been the stronghold of breeding pairs of hen harriers in England – twenty-plus pairs in the 1980s. From then on, the productivity of the birds yo-yo’d up and down every two or three years. Now, in 2012, we’re down to one breeding pair.’

A survey of hen harriers in the British Isles was carried out in 2010. There were then 630 pairs, with the great majority – five hundred-plus pairs – in Scotland, small populations in Wales and Northern Ireland of just under sixty pairs, and a diminishing population of thirty pairs on the Isle of Man. In England the breeding population was a mere twelve pairs, although conservationists tell us that there is suitable moorland habitat for three hundred-plus pairs.

March 2011, Norfolk. The cold darkness before sunrise after a sharp overnight frost. The three-year-old male hen harrier stood up from his roosting place, a soft couch in an area of sphagnum bog surrounded by rushes, heather and dwarf silver birch. Deep within his body chemical changes were taking place, urging him to fly north and seek a mate, forces that would shape everything that would happen in the future. He scanned the roost and counted the dark shapes – four other harriers nearby. It was common land and had been used by harriers as a safe roosting place for centuries.

The harrier stepped forward and cast up a pellet, an oblong mass of fur, feather and bones. He had arrived two days earlier, having overwintered in France, and was now in peak condition. The first light of the rising sun showed a very handsome bird: bright orange eyes, the cere above his sharply curved beak bright yellow, his body – apart from his scapulars and mantle, which were a dusky brown – covered in a silver-grey plumage, black primaries, grey tail and long yellow legs with sharp black talons. He took off, and as he circled higher and higher he saw beneath him the sugar beet fields, where yesterday he had hunted for finches, pipits and migrant thrushes. A few pink-footed geese, stragglers, were flighting in to feed on the sugar beet tops. Further on he skirted the Wash, a vast mud flat separating Norfolk from Lincolnshire. He saw huge flocks of wading birds taking to the air and flying inland as the rising tide covered the glistening mud.

Deep within his brain, information stored from his first view of the nest in which he was hatched directed the sturdy pectoral muscles in his chest, forcing his spread wings down, driving him forward. At the end of each stroke other muscles retracted the wing, ready for the next driving forward stroke. He was heading two hundred miles north-west to the Forest of Bowland, where he had been born three years ago.

Halfway through the Mesolithic Age, ten thousand years ago, the hen harrier would have been a common sight in England. Then, there were millions of acres of heaths, moors, mountains and barren lands. These, together with undrained bogs and marshes, would have provided huge areas of suitable hunting and nesting habitat for harriers to enjoy. The late Derek Yalden and Umberto Albarella found just such a landscape in the Bialowieza National Park on the Polish–Byelorussian border, and in their historical reconstruction they described what bird life would have been like in Britain at that time. Taking the average densities in areas studied by experts in Britain and combining them with the fact that there would have been no persecution or interference, Yalden and Albarella were able to calculate a Mesolithic hen harrier population of 2,803 pairs.

Mesolithic man, a hunter-gatherer, made little impact on the landscape. It was Neolithic man, who arrived in Britain five thousand years ago, who began clearing forest and scrub to make fields. He planted grain crops and his livestock grazed the grasslands on the chalk areas. The sophistication of farming increased during the Bronze Age, when the importance of soils and a good supply of water became understood. The village, in its simplest form, was a cluster of dwellings surrounded by three common fields, fertile and easy to farm, with ox-drawn ploughs being used to strip-plough the land. One of the fields would be planted with wheat or rye for bread, another with grains for beverages and the third would lie fallow. After the Norman Conquest churches were built in each village, the population quadrupled, and farming and clearance of the scrub and forest accelerated. But the yields of grain were poor, barely sufficient to feed the population.

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.