Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

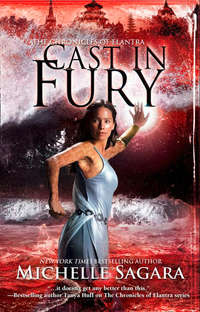

Kitabı oku: «Cast In Fury», sayfa 2

He nodded again. “It’s natural. Kaylin, I’m five years older than you are. Five years ago—”

“It’s not your age,” she said, swatting the words away. Willing to be this truthful. “It’s you.”

“Perhaps. But I have often found understanding my enemies gives me an edge when confronting them.” He paused and then added, “The first Tha’alani I met was Ybelline herself.”

“You met her first?”

“I was under consideration for the Shadows,” he told her. “Ybelline could read everything of note, and still remain detached. There are very few others who could. She was summoned. And it is very, very hard to fear Ybelline.”

Kaylin smiled at this. It was a small smile, but it acknowledged the truth: it was hard to fear her. Even though she could ferret all truth, all secrets, from a human mind. Because in spite of it, one had the sense that Ybelline could know everything and like you anyway.

Maybe that was something they could work with.

CHAPTER 2

Kaylin’s first impression of Richard Rennick could be summed up in two words: Oh, god.

She wasn’t fussy about which god, either. She was pretty sure she couldn’t name half of the ones that figured in official religions, and of the half she could name, the spelling or accents would be off. One of the things that living in the fiefs taught you was that it didn’t particularly matter which god you prayed to—none of them listened, anyway.

Rennick looked like an Arcanist might look if he had been kept from sleep for a week, and kept from the other amenities that came with sleep—like, say, shaving utensils—for at least as long, if not longer. His hair made her hair look tidy. It wasn’t long, but it couldn’t be called short either, and it seemed to fray every which way the light caught it. He didn’t have a beard, and he didn’t have much of a chin, either. It was buried beneath what might, in a few long weeks, be a beard—but messier.

His clothing, on the other hand, was very expensive and had it been on any other person, would have gone past the border of ostentatious; on him it looked lived in. She thought he might be forty. Or thirty. It was hard to tell.

What wasn’t hard to tell: he was having a bad day. And he wasn’t averse to sharing.

He didn’t have manners, either. When Sanabalis entered the room, he looked up from his desk—well, from the very, very long dining table at which he was seated—and grunted in annoyance.

The table itself was what one would expect in the Palace—it was dark, large, obviously well oiled. But the surface was covered in bits and pieces of paper, some of it crumpled in balls that had obviously been thrown some distance. Not all of those were on the table; the carpets had their fair share too.

“Mr. Rennick,” Lord Sanabalis said, bowing. “Forgive me for intruding.”

Another grunt. Sanabalis didn’t even blink an eye.

“I would like to introduce you to Corporal Handred and Private Neya. These are the people Ybelline Rabon’alani spoke of when we last discussed the importance of your work.”

He looked up at that, and managed to lose some slouch. “I hope you last longer than my previous assistants.”

“You had other assistants for this?”

“Oh, not for this project. In general, the office of Official Imperial Playwright comes with assistants.” The sneer that he put in the words managed to remain off his face. Barely.

“They won’t, however, allow me to hire my own assistants, and the ones they’ve sent me must have been dredged from the bottom of the filing pool.”

Kaylin gave Sanabalis what she hoped was a smile. She moved her lips in the right direction.

“We don’t intend to interfere in any way,” she began.

“Oh, please. Take a number and stand in line. If you somehow—by some small miracle—manage not to interfere, you’ll be the only people in this godsforsaken Palace who haven’t tried to tell me how to do my job.”

Sanabalis offered Kaylin a smile that was at least as genuine as hers had been.

On the other hand, if the Emperor hadn’t eaten Rennick, things obviously weren’t as formal as all that, and Kaylin felt a surprisingly strong relief; she was almost happy to have met him. Or would have been, if it were all in the past.

“This is not like filing,” he added, clearly warming up. He even vacated his seat and shoved his hands into pockets that lined the seams of his robes. “This is not an exact bloody science. Do you have any idea what they’ve asked of me?”

She had a fairly good idea, but said, “No.”

Something in her tone caused his eyes to narrow and Severn’s foot to stray slightly closer to hers. But she offered what she hoped was a sympathetic grimace; it was all she was up for.

“No, you probably don’t. But I’ll tell you.”

Of this, no one could be in any doubt.

“They want me to write a play that makes the Tha’alani human.”

There was certainly a sneer in his expression now, and Kaylin had to actively work to keep her hands from becoming fists. You’ve said worse, she told herself. You’ve said a lot worse.

Yes, she added, but he’s never going to go through what you did to change your bloody mind. Because she was used to arguing with herself, she then thought, And we’re going to have to do what experience won’t. Oh, god.

“I am willing to face a challenge,” he added. “Even one as difficult as this—but the Tha’alani themselves don’t seem to understand the purpose of the play I did write. They said it wasn’t true. I told them I wanted a bigger truth. It wasn’t real, but truth isn’t always arrived at by the real.”

“I can see how that would confuse them,” she offered.

“And now they’ve sent you. Have you ever even seen one of my plays?”

“I haven’t seen a play that wasn’t written for children,” she replied.

This didn’t seem to surprise him. He seemed to expect it.

Severn, however, said, “I have.”

“Oh, really?” A voice shouldn’t have legally been able to contain that much sarcasm. And, Kaylin thought, a person shouldn’t be subject to as much sarcasm as this twice in a single day. “Which one?”

“Winter,” Severn replied.

Rennick opened his mouth, but for the moment, he seemed to have run out of words. His eyes widened, his jaw closed, and his lips turned up in a genuine smile. Thirty, Kaylin thought. Or maybe even younger. “That was my second play—I wrote it before I won the seat.” He paused, and then his eyes narrowed. “Where did you see it?”

“It was staged in the Forum,” Severn replied, without missing a beat. “Constance Dargo directed it. I believe the actress who played the role of Lament was—”

“Trudy.”

“Gertrude Ellen.”

“That would be Trudy.” His eyes, however, had lost some of their suspicion. “She could be such a bitch. But she made a number of good points about some of the dialogue.”

“The dialogue was changed?”

“Good god, yes. Dialogue on the page is always stiffer than spoken dialogue—you can’t get a real sense of what it sounds like until actors put it through its paces. The first staging of any play defines the play. What did you think of it?”

“I thought it very interesting, especially given where it played, and when. It was also unusual in that it didn’t feature a relationship as its central motivation.”

“Starving people seldom have the time to worry about social niceties.”

Severn glanced at Kaylin.

“But you might be the first person sent me who’s actually familiar with my work,” Rennick said, picking up the reins where he had dropped them.

“And as one such person, I have no intention of guiding your work. You know it. I don’t.”

“And let me tell you—you don’t … Oh.”

“But the Emperor’s dictates are clear,” Severn continued, into the very welcome silence. “Winter was a work that reached out to people who had everything and reminded them, for a moment, of the fate of the rest of the city. You were chosen to write this for a reason.”

“I was chosen because they don’t have to pay me more.”

At that, Kaylin did chuckle. Rennick actually looked in her direction, but the hostility had ebbed. Slightly. As far as Rennick seemed to be concerned, Dragons didn’t exist, and he didn’t bother to glance at Sanabalis.

Kaylin did. The Dragon’s eyes were a placid gold. Clearly, he had met Rennick before, and for some reason, he had decided not to kill him then.

“Look,” Rennick added, running his hands through his hair as if he would like to pull it all out by its roots, “Winter wasn’t meant to be a message. It wasn’t meant to tell the audience anything about the state of the poor or the starving. I loved Lament—I wanted to tell her story in a way that would move people. Talia Korvick was the first Lament—I’ll grant that Trudy did a better job, but Trudy wouldn’t touch my unknown little play for its first staging.”

The idea that Rennick cared about moving anyone in a way that didn’t mean out of my sight surprised Kaylin. Almost as much as the fact that he would admit it.

“You achieved that—but you also made people think about what her life entailed, and how her life might have been different.”

“Yes—but that was incidental. I don’t know how to make people think differently. And the Emperor appears to want me to … to educate people. With characters that are in no way my own creations. It’s dishonest,” he added.

Given that he told lies for a living, this struck Kaylin as funny. Sanabalis, however, stepped on her foot.

“Lament wasn’t a real person but you made her real. The Tha’alani are real in the same way that the rest of us are—and Lament was human.” Severn frowned slightly, his thinking expression. “Have you been out in the streets since the storm?”

Rennick frowned. “Not far, no.”

“People are afraid. Frightened people are often ugly people. The Tha’alani—”

“From all reports, they tried to kill us.”

Kaylin didn’t care at that moment if Sanabalis stepped on her foot and broke it. “By standing in the way of the tidal wave? They would have been the first people hit by the damn thing!”

Rennick actually looked at her, possibly for the first time. After a moment, he said, “There is that.”

“Look, I don’t know what you’ve heard, and I don’t bloody care—they tried to save the city. And if this is what they get for trying to save it, they should have just let it drown.”

“And you know this how?”

“I was there—” She shut her mouth. Loudly. “I’m the cultural expert,” she told him instead.

“You were there?”

“She was not,” Sanabalis said, speaking in his deep rumble. “But she is a friend of the Tha’alani, and as much as anyone who was not born Tha’alani can, she now understands them. Mr. Rennick, I am aware that you find the current assignment somewhat stressful—”

“The Imperial Playwright writes his own work,” Rennick snapped. “This is—this is political propaganda.”

“But what you write, and what you stage—provided any of the directors available meet your rather strict criteria—will influence the city for decades to come. It is necessary work, even if you find it distasteful.”

“In other words,” Kaylin added sweetly, “The Emperor doesn’t care what you think.”

Severn glanced at Kaylin, and his expression cleared. Whatever he had been balancing in the back of his mind had settled into a decision. “With your leave, Lord Sanabalis, we have duties elsewhere.”

“What?” Rennick glared at Severn. “You definitely haven’t outlasted the previous assistants.”

“Our presence has been requested by the castelord of the Tha’alani,” he continued, ignoring Rennick—which might, to Kaylin’s mind, be the best policy. “And if you think it would be of help to you, you may accompany us.”

Hard to believe that only a few weeks ago, Kaylin would have skirted this Quarter of the town as if it had the plague. Fear made things big; her mental map of the Tha’alani district had been a huge, gray shadow that would, luck willing, remain completely in the dark.

Now, it seemed small. It had one large gate, and way too few guards—usually one—between it and the rest of the city. The only people who left the Quarter for much of anything were the Tha’alani seconded to the Imperial Service—and like many, many people in Elantra, they hated their jobs. Of course they did their jobs to prevent the Emperor from turning their race into small piles of ash, but they didn’t make this a big public complaint.

And they still liked the Hawks. Kaylin privately thought that was crazy—in their situation, she wouldn’t have.

Lord Sanabalis had arranged for a carriage, but he had not chosen to accompany them to the Quarter. This was probably for the best, as a Dragon wandering the streets could make anyone who noticed him nervous. On the other hand, people were already nervous, and if they wanted to take it out on something, Kaylin privately had a preference for something that could fight back, although she conceded that this was a fief definition of the word “fight.”

Rennick was silent for the most part, which came as a bit of a shock. He stuck his head out the window once or twice when something caught his eye, and he frequently stuck his arm out as if writing on air, but Severn said nothing; clearly Rennick was not of a station where babysitting was considered part of their duties.

But he pulled both arm and head into the carriage when they at last began the drive up Poynter’s road, because even Rennick could tell that the bodies on this particular street were on the wrong side of “tense.” They were like little murders waiting to happen.

“Don’t they have anything better to do?” she muttered to Severn.

He said nothing.

It was Rennick who said, “Probably not. They don’t want the Tha’alani to leave the Quarter, and they’re making sure that they don’t. Hey! That man has a crossbow!”

Kaylin had seen it. The fact that it was still in his hands implied that the Swords had far more work than they should have, and it troubled her. But not enough that she wanted to stop the carriage, get down and start a fight.

Because it would be a fight, and it would probably get messy.

“They’re frightened,” she said, surprising herself.

“Funny how frightened people can be damn scary,” Rennick replied. But he looked thoughtful, not worried.

“How many?” Kaylin asked Severn.

“A hundred and fifty, maybe. Some of them are in the upper windows along the street. I imagine that the Tha’alani who serve the Emperor are being heavily escorted.”

“Or given a vacation.”

He nodded.

“Has there been any official word about the incident?” Rennick asked quietly.

Kaylin shrugged.

“You don’t know?”

“Right up until one of those idiots fires his crossbow or swings his—is that a pickax?” Severn nodded. “Swings his ax,” she continued, “it’s not Hawk business. It’s Sword, and the Swords are here.”

And they were. Kaylin had thought they’d send twenty men out; she was wrong by almost an order of magnitude. She thought there were maybe two hundred in total—no wonder the Halls of Law were so damn quiet.

But while they lined the street, they hadn’t built an official barricade, they did meet the carriage in the road, well away from the gatehouse, and they did tell the driver to step down. They also opened the doors, and Kaylin made sure she tumbled out first.

“Private Neya?” said the man who had delivered the curt instructions. He was older than Kaylin by about fifteen years, and the day seemed to have added about a hundred new wrinkles, and a layer of gray to his skin, but she recognized him. “Max—Uh, Sergeant,” she added, as he looked pointedly over her soldier. “Sergeant Voone. You’re out here?”

Max wasn’t retired, exactly, but he spent a lot of his time behind a desk. He appeared to like it a great deal more than Marcus—but a corpse would have given that impression as well. And Max looked tired.

“Most of us are, as you put it, out here. I know why we’re here—what are you doing in a fancy box?”

“Oh. Uh, we were sent here.”

“By?”

“Lord Sanabalis.”

He whistled. “To do what?”

“Not to step all over your toes, relax.”

His chuckle was entirely mirthless. “We’ll relax when these people remember they have jobs and family.”

“I’m thinking they remember the family part,” Kaylin replied. “People go crazy when they think they’re protecting their own.”

“Tell me about it. No, strike that. Don’t.”

“When did it get this bad?”

“There was an incident two days ago.”

“Incident?”

“It was messy,” he replied, his voice entirely neutral. “The Swordlord made it clear that there will be no more incidents. The Emperor was not impressed.”

She winced. It wasn’t often that she felt sympathy for the Swords. But while she resented the easy life the Swords generally called work, she liked them better than the people with the crossbows down the street.

“You know they’re armed?” she asked casually.

“We are well aware that they’re armed. And no, thank you, we don’t require help in disarming them. They’re waiting for an invitation. Let them wait. At that distance.”

She looked at Severn as Severn exited the carriage. Rennick tumbled out after him. “Sergeant Voone,” Severn said, before the sergeant could speak, “Richard Rennick. He’s the Imperial Playwright.”

“This is not a good time for sightseeing,” the Sword said to Rennick.

Rennick looked him up and down, and then shrugged. “It wasn’t my idea.” But he was subdued, now. He lifted a hand to his face, rubbing the scruff on his chin.

“You can call the Hawks out,” Kaylin continued. “At least the Aerians—”

“We’ve got Aerians here. They’re not currently in the air,” he added. And then he gave her an odd look. “The Hawks have their own difficulties to worry about. I was sorry to hear the news.”

“What news?”

His whole expression shuttered, not that it was ever all that open.

“Voone, what news? What’s happened?”

“You came from the Halls?”

“The Halls don’t usually have access to Imperial Carriages. What happened?”

“No one died,” he replied, and his tone of voice added yet. “But you might want to check in at the office before you head home.”

She wanted to push him for more, but Severn shook his head slightly. “Ybelline.”

There was no Tha’alani guard at the guardhouse. That position was taken up by a dozen Swords. They wore chain, and they carried unsheathed swords. You’d have to be crazy to rush the gatehouse.

Kaylin approached it quietly and answered the questions the Swords asked; they were all perfunctory. Voone escorted them to the squad and left them there, after mentioning her name loudly enough to wake the dead. She noted all of this and tried to squelch her own fear. Severn was right, of course. They’d come here for Ybelline. But the sympathies of Voone made her nervous.

The Swords hadn’t entered the Quarter; they were met by Tha’alani guards. Four men in armor. Their stalks swiveled toward her as she entered.

She saw that they, too, bore unsheathed swords, and it made her … angry. Those weapons just looked wrong in Tha’alani hands; she wondered if they even knew how to use them.

But using them wasn’t an issue. They bowed to her, almost as one man. “Ybelline is waiting for you,” one told her quietly.

“At her house?”

“Not at her domicile. Demett will take you to her.” The man so identified stepped away from his companions.

“Where is she?”

“At the longhouse” was his reply—spoken in the stiff and exact cadence that Tha’alani who were unused to speech used. He obviously expected her to know what the longhouse was, and she didn’t bother to correct him.

She followed him, and it took her a moment to realize why the streets here felt so wrong—they were empty. Usually walking down a Tha’alani street was like walking in the Foundling Hall—it was a gauntlet of little attention-seeking children, with their open curiosity and their utter lack of decorum.

She didn’t care for the change. Hell, even the plants were drooping. Rennick walked between Severn and her, and made certain that there was always at least one body between him and the nearest Tha’alani. He wasn’t overly obvious about it, but it rankled. Even when Kaylin had been terrified of the Tha’alani, she wouldn’t have tried to hide. One, it wouldn’t have done much good and two—well, two, she didn’t casually throw strangers to fates she herself feared.

It was not going to be easy working with Rennick. She spared him a glance every so often, which was more than any of the Tha’alani did. They hadn’t even questioned his presence. It would have been convenient if they had. He’d be on the other side of the gates, where he’d be marginally less annoying.

The guards walked past the latticework of open—and utterly empty—fountains; past the blush of bright pink, deep red and shocking blue flower beds that bordered them; past the neat little circular domes that reminded Kaylin of nothing so much as hills. And if those homes were hills, they were approaching a small fortress that nestled among them. It was two stories tall, and the beams that supported the clay face were almost as wide as she was, and certainly taller. It was larger by far than the building in which Ybelline, the castelord—a word that didn’t suit her at all—chose to live. It was almost imposing.

It was also bloody crowded.

It boasted normal doors—rectangular doors, not the strange ones that adorned most of the Tha’alani homes; these doors weren’t meant to blend with the structure. They stood out. And they were pulled wide and pegged open. Which, given the number of people on the other side of them, made sense—closed doors would have made breathing anything but stale air and sweat almost impossible. As it was, it was dicey.

“This is the longhouse,” Kaylin said.

Demett nodded.

“Demett,” she said, as he turned, “what is the longhouse used for?”

His face went that shade of expressionless that actually meant he was talking—but only to the Tha’alaan: to the minds of his people, and the memories of the dead. She waited for it to pass, as if it were a cloud; it took a while.

“Wait for Ybelline,” he told her quietly.

Ybelline came through the crowd slowly. You could see where she might be moving because her movement caused the other Tha’alani to move, like a human wave composed entirely of bodies. The building was packed. Kaylin thought there might be six or seven hundred people just beyond the open doors, more if the children so absent from the streets were also there.

But Ybelline did not come alone; the movement of the crowd, the slow outward push, wouldn’t have been necessary to allow just one person through. The people spilled out into the streets, beyond Kaylin and Severn. Rennick’s shoulders curled in, and he brought his hands up once or twice, as if to fend off any contact.

The Tha’alani in turn avoided him.

They would. They knew fear when they saw it, especially Rennick’s fear—and his fear was poison to them. They tried just as hard as he did to avoid any contact, but Kaylin had to admit they were more polite about it.

Ybelline appeared at last, between the shoulders of about sixteen tightly grouped men and women. She wore robes, an earth-brown with green edges; her hair was arranged both artlessly and perfectly above her slender neck. Her eyes were the honey-brown of that hair, but they were ringed with gray circles. She looked exhausted.

Exhaustion did not stop her from opening her arms, stepping forward and hugging Kaylin. And nothing in the world would have stopped Kaylin from returning that hug. Nothing.

“Tell me,” she whispered, her lips beside Ybelline’s ear. She knew she should have introduced Rennick, but it had been Severn’s idea to drag him here, and he was therefore, for the moment, Severn’s problem.

The slender stalks, which were the most obvious racial trait of all the Tha’alani, brushed strands of Kaylin’s hair from her forehead, and then settled gently against skin.

They were so delicate, the touch so light, they could hardly be felt at all.

But Ybelline could be—and more, she could be clearly heard. Could clearly hear. With this much contact, she could, if she wanted to, peruse every memory Kaylin had, including ones she wasn’t aware of herself. All the hidden things could be revealed, every bad or stupid or humiliating thing Kaylin had ever done.

And Kaylin, knowing this, didn’t care.

But she wasn’t prepared for Ybelline’s voice when it came. It was raw and, at first, there were no words—just the sense of things that might have become words with enough distance and effort. With too much distance and effort.

But she saw what Ybelline meant her to see in the brief glimpse of steel and blood and the bodies of the fallen, all interposed, all flashing over and over again in quick succession in front of Kaylin’s eyes. Except that her eyes were closed.

Help me. Just that, two words.

Kaylin rolled up her sleeves and, without even looking at her wrist, pressed the gems on the bracer in the sequence that would open it: white, blue, white, blue, red, red, red. She dropped it on the ground as if it were garbage—but she could. If she’d tossed it on a garbage heap, it would find its way back to her. She’d only tried that once. Maybe twice.

This was magic’s cage. And without it, she was free to do whatever she could. For this reason it was technically against orders to remove it.

Her hands were tingling. “Ybelline,” she said, and then, Ybelline.

Ybelline, you have to let go of me.

The Tha’alani castelord did as Kaylin bid; she let go, withdrew her arms, her stalks. With them went the wild taste of fear—Ybelline’s fear. She kept it from the Tha’alaan, and therefore from her people, but she was exhausted. And Kaylin understood the exhaustion; it was hard for any Tha’alani to live alone, on the inside of their thoughts, the way humans did.

The way humans needed to.

The Tha’alani who had followed Ybelline out of the longhouse had come bearing stretchers. Four stretchers. Four men. They might once have worn armor—had, Kaylin thought, remembering the brief flash of images that had emerged from her contact with Ybelline.

But they weren’t dead. They weren’t dead yet.

“Put them down,” Kaylin said, easing her voice into the command that came naturally when she was on the beat. There were no children here; she had time to notice their absence, to be grateful for it. No more.

The crowd stepped back. The bodies lay on stretchers. Someone had dressed wounds, had cleaned burns—burns!—had done what they could to preserve life. Freed of the constraints that the ancient bracer placed on her magic, Kaylin knelt between two of these stretchers and touched two foreheads with her right and left palms. She was gentle, although she didn’t have to be—the men here were in no danger of regaining consciousness anytime soon. They had that gray-white pallor that spoke of loss of blood. She was surprised that they hadn’t succumbed to the wounds they had taken. Many of those wounds weren’t clean cuts; they had been caused by people who weren’t used to handling weapons.

Kaylin grimaced. “Severn?”

She saw his shadow. Knew he was listening.

“Get water,” she told him. “I’ll need it.”

“There are four men—”

“I can do this. Just—water. Food.”

His shadow was still for a moment, but he was silent. Everything they said or did now—every single thing—would be watched by all of the Tha’alani, no matter where they were, no matter how young or how old, how strong or how weak. All of the Tha’alani who watched would see, and what they saw would become part of the Tha’alaan, the living memory of the entire race; Tha’alani children four hundred years from now could search the Tha’alaan and see the events of this day through the eyes of these witnesses.

And for once in her life, Kaylin was determined to make a good impression.

Severn knew; he wasn’t an idiot. He knew that humans—her kind, and his—had done this damage. He knew how important it was to the city that humans be seen to undo it. She didn’t even hear him go.

It was hard.

It was harder than destroying walls that were solid stone, harder than killing a man. Healing always was. It was harder than saving infants who were trapped in a womb; harder, even, than holding their mothers when shock and loss of blood threatened their lives.

Harder than saving a child in the Foundling Hall.

But she had done all of that.

She felt the shape of their bodies and the beat—erratic and labored—of their hearts. She heard their thoughts, not as thoughts, but as memories, almost inseparable from her own. She felt their injuries, the broken bones, the old scars from—falling out of a tree? She even snorted. These weren’t men who got caught out in bar brawls.

They weren’t men who were accustomed to war of any kind.

She could save them. She could see where infection had taken its toll, eating into flesh and muscle. Two men. If she wanted them to live, she couldn’t use any more power than was absolutely necessary. No miracles, not yet. No obvious miracles.

But the subtle ones were the only ones that counted.

The bones that would knit on their own, she left; the ones that wouldn’t mend properly, she fixed. She tried not to see what had caused the breaks, but gave up quickly. That took too much effort, too much energy.

When she lifted her hands from their faces, she felt the touch of their stalks, clinging briefly to her skin. She told them to sleep.

She heard Ybelline’s voice. Felt Severn’s hands under her arms, shoring her up as she stood and wobbled. She didn’t brush him off, didn’t try. She let him carry some of her weight as she approached the last two men, their stretchers like pale bruises on the ground.

She felt grass beneath her knees as she crushed it, folding too quickly to the ground. Righting herself, which really meant letting Severn pick her up, she reached out to touch them.

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.