Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

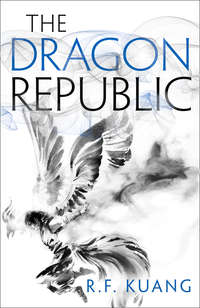

Kitabı oku: «The Dragon Republic»

THE DRAGON REPUBLIC

R. F. Kuang

Copyright

HarperVoyager

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2019

Copyright © Rebecca Kuang 2019

Maps by Eric Gunther, copyright © Springer Cartographics 2017, 2019

Cover illustration © JungShan

Cover design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2019

R.F. Kuang asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008239855

Ebook Edition © July 2019 ISBN: 9780008239879

Version: 2019-07-11

Dedication

To

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Maps

Arlong, Eight Years Prior

Part I

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Part II

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Part III

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Dramatis Personae

Acknowledgments

Also by R. F. Kuang

About the Publisher

Maps

ARLONG, EIGHT YEARS PRIOR

“Come on,” Mingzha begged. “Please, I want to see.”

Nezha seized his brother by his chubby wrist and pulled him back from the shallows. “We’re not allowed to go past the lily pads.”

“But don’t you want to know?” Mingzha whined.

Nezha hesitated. He, too, wanted to see what lay in the caves around the bend. The grottoes of the Nine Curves River had been mysteries to the Yin children since they were born. They’d grown up with warnings of dark, dormant evils concealed behind the cave mouths; of monsters that lurked inside, eager for foolish children to stumble into their jaws.

That alone would have been enough to entice the Yin children, all of whom were adventurous to a fault. But they’d heard rumors of great treasures, too; of underwater piles of pearls, jade, and gold. Nezha’s Classics tutor had once told him that every piece of jewelry lost in the water inevitably wound up in those river grottoes. And sometimes, on a clear day, Nezha thought he could see the glimmer of sunlight on sparkling metal in the cave mouths from the window of his room.

He’d desperately wanted to explore those caves for years—and today would be the day to do it, when everyone was too busy to pay attention. But it was his responsibility to protect Mingzha. He’d never been trusted to watch his brother alone before; until today he’d always been too young. But this week Father was in the capital, Jinzha was at the Academy, Muzha was abroad at the Gray Towers in Hesperia, and the rest of the palace was so frazzled over Mother’s sudden illness that the servants had hastily passed Mingzha into Nezha’s arms and told them both to keep out of trouble. Nezha wanted to prove he was up to the task.

“Mingzha!”

His brother had wandered back into the shallows. Nezha cursed and dashed into the water behind him. How could a six-year-old move so quickly?

“Come on,” Mingzha pleaded when Nezha grabbed him by the waist.

“We can’t,” Nezha said. “We’ll get in trouble.”

“Mother’s been in bed all week. She won’t find out.” Mingzha twisted around in Nezha’s grip and shot him an impish smile. “I won’t tell. The servants won’t tell. Will you?”

“You’re a little demon,” Nezha said.

“I just want to see the entrance.” Mingzha beamed hopefully at him. “We don’t have to go in. Please?”

Nezha relented. “We’ll just go around the bend. We can look at the cave mouths from a distance. And then we’re turning back, do you understand?”

Mingzha shouted with delight and splashed into the water. Nezha followed, stooping down to grab his brother’s hand.

No one had ever been able to deny Mingzha anything. Who could? He was so fat and happy, a bouncing ball of giggles and delight, the absolute treasure of the palace. Father adored him. Jinzha and Muzha played with him whenever he wanted, and they never told him to get lost the way Jinzha had done so often to Nezha.

Mother doted on him most of all—perhaps because her other sons were destined to be soldiers, but she could keep Mingzha all to herself. She dressed him in finely embroidered silks and adorned him with so many lucky amulets of gold and jade that Mingzha clinked everywhere he walked, weighed down with the burden of good fortune. The palace servants liked to joke that they could always hear Mingzha before they saw him. Nezha wanted to make Mingzha stop to remove his jewelry now, worried it might drag him down under waves that already came up to his chest, but Mingzha charged forward like he was weightless.

“We’re stopping here,” Nezha said.

They’d gotten closer to the grottoes than they had ever been in their lives. The cave mouths were so dark inside that Nezha couldn’t see more than two feet past the entrances, but their walls looked beautifully smooth, glimmering with a million different colors like fish scales.

“Look.” Mingzha pointed at something in the water. “It’s Father’s cloak.”

Nezha frowned. “What’s Father’s cloak doing at the bottom of the river?”

Yet the heavy garment lying half-buried in the sand was undeniably Yin Vaisra’s. Nezha could see the crest of the dragon embroidered in silver thread against the rich cerulean-blue dye that only members of the House of Yin were permitted to wear.

Mingzha pointed to the closest grotto. “It came from in there.”

An inexplicable, chilly dread crept through Nezha’s veins. “Mingzha, get away from there.”

“Why?” Mingzha, stubborn and fearless, waded closer to the cave.

The water began to ripple.

Nezha reached out to pull his brother back. “Mingzha, wait—”

Something enormous burst out of the water.

Nezha saw a huge dark shape—something muscled and coiled like a serpent—before a massive wave rose above him and slammed him facedown into the water.

The river shouldn’t have been deep. The water had only come up to Nezha’s waist and Mingzha’s shoulders, had only been getting shallower the closer they moved to the grotto. But when Nezha opened his eyes underwater, the surface seemed miles away, and the bottom of the grotto seemed as vast as the palace of Arlong itself.

He saw a pale green light shining from the grotto floor. He saw faces, beautiful, but eyeless. Human faces embedded in the sand and coral, and an endless mosaic studded with silver coins, porcelain vases, and golden ingots—a bed of treasures that stretched on and on into the grotto as far as the light went.

He saw a blink of movement, dark against the light, that disappeared as quickly as it came.

Something was wrong with the water here. Something had stretched and altered its dimensions. What should have been shallow and bright was deep; deep, dark, and terribly, hypnotically quiet.

Through the silence Nezha heard the faint sound of his brother screaming.

He kicked frantically for the surface. It seemed miles away.

When at last he emerged from the water, the shallows were mere shallows again.

Nezha wiped the river water from his eyes, gasping. “Mingzha?”

His brother was gone. Crimson streaks stained the river. Some of the streaks were solid, lumpy masses. Nezha knew what they were.

“Mingzha?”

The waters were quiet. Nezha stumbled to his knees and retched. Vomit mixed into bloodstained water.

He heard a clink against the rocks.

He looked down and saw a golden anklet.

Then he saw a dark shape rising before the grottoes, and heard a voice that came from nowhere and vibrated his very bones.

“Hello, little one.”

Nezha screamed.

PART I

CHAPTER 1

Dawn saw the Petrel sail through swirling mist into the port city of Adlaga. Shattered by a storm of Federation soldiers during the Third Poppy War, port security still hadn’t recovered and was almost nonexistent—especially for a supply ship flying Militia colors. The Petrel glided past Adlaga’s port officers with little trouble and made berth as close to the city walls as it could get.

Rin propped herself up on the prow, trying to conceal the twitching in her limbs and to ignore the throbbing pain in her temples. She wanted opium terribly and couldn’t have it. Today she needed her mind alert. Functioning. Sober.

The Petrel bumped against the dock. The Cike gathered on the upper deck, watching the gray skies with tense anticipation as the minutes trickled past.

Ramsa drummed his foot against the deck. “It’s been an hour.”

“Patience,” Chaghan said.

“Could be that Unegen’s run off,” Baji said.

“He hasn’t run off,” Rin said. “He said he needed until noon.”

“He’d also be the first to seize this chance to be rid of us,” Baji said.

He had a point. Unegen, already the most skittish by far among the Cike, had been complaining for days about their impending mission. Rin had sent him ahead overland to scope out their target in Adlaga. But the rendezvous window was quickly closing and Unegen hadn’t shown.

“Unegen wouldn’t dare,” Rin said, and winced when the effort of speaking sent little stabs through the base of her skull. “He knows I’d hunt him down and skin him alive.”

“Mm,” Ramsa said. “Fox fur. I’d like a new scarf.”

Rin turned her eyes back to the city. Adlaga made an odd corpse of a township, half-alive and half-destroyed. One side had emerged from the war intact; the other had been bombed so thoroughly that she could see building foundations poking up from blackened grass. The split appeared so even that half houses existed on the line: one side blackened and exposed, the other somehow teetering and groaning against the ocean winds, yet still standing.

Rin found it hard to imagine that anyone still lived in the township. If the Federation had been as thorough here as they’d been at Golyn Niis, then all that should be left were corpses.

At last a raven emerged from the blackened ruins. It circled the ship twice, then dove straight toward the Petrel as if locked on a target. Qara lifted a padded arm into the air. The raven pulled out of its dive and wrapped its talons around her wrist.

Qara ran the back of her index finger over the bird’s head and down its spine. The raven ruffled its feathers as she brought its beak to her ear. Several seconds passed. Qara stood still with her eyes shut, listening intently to something the rest of them couldn’t hear.

“Unegen’s pinned Yuanfu,” Qara said. “City hall, two hours.”

“Guess you’re not getting that scarf,” Baji told Ramsa.

Chaghan yanked a sack out from under the deck and emptied its contents onto the planks. “Everyone get dressed.”

Ramsa had come up with the idea to disguise themselves in stolen Militia uniforms. Uniforms were the one thing Moag hadn’t been able to sell them, but they weren’t hard to find. Rotting corpses lay in messy piles by the roadside in every abandoned coastal town, and it took only two trips to scavenge enough clothes that weren’t burned or covered in blood.

Rin had to roll up the arms and legs of her uniform. Corpses of her stature were difficult to come by. She suppressed the urge to vomit as she laced on her boots. She’d pulled the shirt off a body wedged inside a half-burned funeral pyre, and three washes still couldn’t conceal the smell of charred flesh under salty ocean water.

Ramsa, draped absurdly in a uniform three times his size, gave her a salute. “How do I look?”

She bent down to tie her boot laces. “Why are you wearing that?”

“Rin, please—”

“You’re not coming.”

“But I want to—”

“You are not coming,” she repeated. Ramsa was a munitions genius, but he was also short, scrawny, and utterly worthless in a melee. She wasn’t losing her only fire powder engineer because he didn’t know how to wield a sword. “Don’t make me tie you to the mast.”

“Come on,” Ramsa whined. “We’ve been on this ship for weeks, and I’m so fucking seasick just walking around makes me want to vomit—”

“Tough.” Rin yanked a belt through the loops around her waist.

Ramsa pulled a handful of rockets from his pocket. “Will you set these off, then?”

Rin gave him a stern look. “I don’t think you understand that we’re not trying to blow Adlaga up.”

“Oh, no, you just want to topple the local government, that’s so much better.”

“With minimal civilian casualties, which means we don’t need you.” Rin reached out and tapped at the lone barrel leaning against the mast. “Aratsha, will you watch him? Make sure he doesn’t get off the ship.”

A blurry face, grotesquely transparent, emerged from the water. Aratsha spent most of his time in the water, spiriting the Cike’s ships along to wherever they needed to go, and when he wasn’t calling down his god he preferred to rest in his barrel. Rin had never seen his original human form. She wasn’t sure he had one anymore.

Bubbles floated from Aratsha’s mouth as he spoke. “If I must.”

“Good luck,” Ramsa muttered. “As if I couldn’t outrun a fucking barrel.”

Aratsha tilted his head at him. “Please be reminded that I could drown you in seconds.”

Ramsa opened his mouth to retort, but Chaghan spoke over him. “Everyone take your pick.” Steel clattered as he dumped out a chest of Militia weapons onto the deck. Baji, complaining loudly, traded his conspicuous nine-pointed rake for a standard infantry sword. Suni scooped up an Imperial halberd, but Rin knew the weapon was purely for show. Suni’s specialty was bashing heads in with his shield-sized hands. He didn’t need anything else.

Rin fastened a curved pirate scimitar to her waist. It wasn’t Militia standard, but Militia swords were too heavy for her to wield. Moag’s blacksmiths had fashioned her something lighter. She wasn’t yet used to the grip, but she also doubted the day would end in a sword fight.

If things got so bad that she needed to get involved, then it would end in fire.

“Let’s reiterate.” Chaghan’s pale eyes roved over the assembled Cike. “This is surgical. We have a single target. This is an assassination, not a battle. You will harm no civilians.”

He looked pointedly at Rin.

She crossed her arms. “I know.”

“Not even by accident.”

“I know.”

“Come off it,” Baji said. “Since when did you get so high and mighty about casualties?”

“We’ve done enough harm to your people,” said Chaghan.

“You did enough harm,” Baji said. “I didn’t break those dams.”

Qara flinched at that, but Chaghan acted as if he hadn’t heard a word. “We’re finished hurting civilians. Am I understood?”

Rin jerked out a shrug. Chaghan liked to play commander, and she was rarely in a state to be bothered. He could boss them around all he liked. All she cared about was that they got this job done.

Three months. Twenty-nine targets, all killed without error. One more head in a sack, and then they’d be sailing north to assassinate their very last mark—the Empress Su Daji.

Rin felt a flush creep up her neck at the thought. Her palms grew dangerously hot.

Not now. Not yet. She took a deep breath. Then another one, more desperate, when the heat only extended through her torso.

Baji clamped a hand on her shoulder. “You all right?”

She exhaled slowly. Made herself count backward from ten, and then up to forty-nine by odd numbers, and then back down by prime numbers. Altan had taught her that trick, and it mostly worked, at least when she took care not to think about Altan when she did it. The fever flush receded. “I’m fine.”

“And you’re sober?” Baji asked.

“Yes,” she said stiffly.

Baji didn’t take his hand off her shoulder. “You’re sure? Because—”

“I’ve got this,” she snapped. “Let’s go gut this bastard.”

Three months ago, after the Cike had first sailed out from the Isle of Speer, they’d faced a bit of a dilemma.

Namely, they had nowhere to go.

They knew they couldn’t return to the mainland. Ramsa had pointed out, quite astutely, that if the Empress had been willing to sell the Cike out to Federation scientists, then she wouldn’t be happy to see them alive and free. A quick, furtive supply trip to a tiny coastal city in Snake Province confirmed their suspicions. All of their faces were plastered on the village post boards. They’d been named as war criminals. Bounties were out for their arrest—five hundred Imperial silvers dead, six hundred alive.

They’d stolen as many crates of provisions as they could and hurried out of Snake Province before anyone saw them.

Back in Omonod Bay, they’d debated their options. The only thing they could all agree on was that they needed to kill the Empress Su Daji—the Vipress, the last of the Trifecta, and the traitor who had sold her nation to the Federation.

But they were nine people—eight, without Kitay—against the most powerful woman in the Empire and the combined forces of the Imperial Militia. They’d had few supplies, only the weapons they carried on their backs and a stolen skimmer so banged up that they spent half their time bailing water out of the lower decks.

So they’d sailed down south, past Snake Province into Rooster territory, tracing the coastline until they reached the port city Ankhiluun. There they had come into the employ of the Pirate Queen Moag.

Rin had never met anyone she respected as much as she did Moag—the Stone Bitch, the Lying Widow, and the ruthless ruler of Ankhiluun. She was a consort-turned-pirate who went from Lady to Queen when she murdered her husband, and she’d been running Ankhiluun as an illegal enclave of foreign trade for years. She’d skirmished with the Trifecta during the Second Poppy War, and she’d been fending off the Empress’s scouts ever since.

She was more than happy to help the Cike rid her of Daji for good.

In return, she demanded thirty heads. The Cike had returned twenty-nine. Most had been low-level smugglers, captains, and mercenaries. Moag’s primary income stream came from contraband opium imports, and she liked to keep her eye out for opium dealers who didn’t play by her rules—or at least line her pockets.

The thirtieth mark would be harder. Today Rin and the Cike intended to topple Adlaga’s local government.

Moag had been trying to break into the Adlaga market for years. The little coastal city didn’t offer much, but its civilians, many with lingering addictions to opiates since the days of Federation occupation, would gladly spend their life savings on Ankhiluuni imports. Adlaga had held out against Moag’s aggressive opium trade for the past two decades only because of a particularly vigilant city magistrate, Yang Yuanfu, and his administration.

Moag wanted Yang Yuanfu dead. The Cike specialized in assassination. They were a matchmaker’s dream.

Three months. Twenty-nine heads. Just one more job and they’d have silver, ships, and enough soldiers to distract the Imperial Guard long enough for Rin to march up to Daji and wrap flaming fingers around her throat.

If port security was lax, wall defense was nonexistent. The Cike passed through Adlaga’s walls with no interference—which wasn’t hard to do, considering the Federation had blown great holes all across the boundary and none of them were guarded.

Unegen met them behind the gates.

“We picked a good day for murder,” he said as he guided them into the alleyway. “Yuanfu’s due in the city square at noon for a war commemoration ceremony. He’ll be out in broad daylight, and we can pick him off from the alleys without showing our faces.”

Unlike Aratsha, Unegen preferred his human form when he wasn’t calling down the shape-shifting powers of the fox spirit. But Rin had always sensed something distinctly vulpine in the way he carried himself. Unegen was both crafty and easily startled; his narrow eyes were always darting from side to side, tracking all of his possible escape routes.

“So we’ve got what, two hours?” Rin asked.

“A little over. There’s a warehouse a few blocks down from here that’s fairly empty,” he said. “We can hunker down to wait in there. Then, ah, we split pretty easily if things go south.”

Rin turned toward the Cike, considering.

“We’ll take the corners of the square when Yuanfu shows up,” she decided. “Suni in the southwest. Baji northwest, and I’ll take the northeast.”

“Diversions?” Baji asked.

“No.” Normally diversions were a fantastic idea, and Rin loved assigning Suni to wreak as much havoc as possible while she or Baji darted in to slit their target’s throat, but during a public ceremony the risk to civilians was too great. “We’ll let Qara take the first shot. The rest of us clear a path back to the ship if they put up resistance.”

“Are we still trying to pretend we’re normal mercenaries?” Suni asked.

“Might as well,” Rin said. They’d done a decent job so far of concealing the extent of their abilities, or at least silencing anyone who would spread rumors. Daji didn’t know the Cike were coming for her. The longer she believed them dead, the better. “We’re dealing with a better opponent than usual, though, so do what you need to. At the end of the day, we want a head in a bag.”

She took a breath and ran the plan once more through her mind, considering.

This would work. This was going to be fine.

Strategizing with the Cike was like playing a chess game in which she had several massively overpowered, unpredictable, and bizarre pieces. Aratsha commanded the waters. Suni and Baji were berserkers, capable of leveling entire squadrons without breaking a sweat. Unegen could transform into a fox. Qara not only communed with birds, she could shoot out a peacock’s eye from a hundred meters away. And Chaghan … she wasn’t quite sure what Chaghan did, other than irritate her at every possible turn, but he seemed capable of making people lose their minds.

All of them combined against a single township official and his guards seemed like overkill.

But Yang Yuanfu was used to assassination attempts. You had to be, if you were one of the few uncorrupt officials left in the Empire. He shielded himself with a squadron of the most battle-hardy men in the province wherever he went.

Rin knew, based on Moag’s reports, that Yang Yuanfu had survived at least thirteen assassination attempts over the past fifteen years. His guards were well accustomed to treachery. To get past them, you’d need fighters of unnatural ability. You needed overkill.

Once inside the warehouse, the Cike had nothing to do but wait. Unegen kept watch by the slats in the wall, twitching continuously. Chaghan and Qara sat with their backs against the wall, silent. Suni and Baji stood slouched, arms crossed casually as if simply waiting for their dinners.

Rin paced the room, focusing on her breathing and trying to ignore the twinges of pain in her temples.

She counted thirty hours since she’d ingested any opium. That was longer than she’d gone for weeks. She twisted her hands together as she walked, trying to force the twitching to go away.

It didn’t help. It didn’t stop the headache, either.

Fuck.

At first she’d thought she only needed the opium for the grief. She thought she would smoke it for the relief, until the memories of Speer and Altan dulled to a faint ache, until she could function without the suffocating guilt of what she’d done.

She thought guilt must be the word for it. The irrational feeling, not the moral concept. Because she’d told herself she wasn’t sorry, that the Mugenese deserved what they got and that she was never looking back. Except the memory loomed like a gaping chasm in her mind where she’d tossed in every human feeling that threatened her.

But the abyss kept calling for her to look in. To fall inside.

And the Phoenix didn’t want to let her forget. The Phoenix wanted her to gloat about it. The Phoenix lived on rage, and rage was intricately tied to the past. So the Phoenix needed to claw apart the open wounds in her mind and set fire to them, day after day, because that gave her memories and those memories fueled the rage.

Without opium the visions flashed constantly through Rin’s mind’s eye, often more vivid than her surrounding reality.

Sometimes they were of Altan. More times they weren’t. The Phoenix was a conduit to generations of memories. Thousands upon thousands of Speerlies had prayed to the god in their grief and desperation. And the god had collected their suffering, stored it, and turned it into flames.

The memories could also be deceptively calm. Sometimes Rin saw brown-skinned children running up and down a pristine white beach. She saw flames burning higher on the shore—not funeral pyres, not flames of destruction, but campfires. Bonfires. Hearth fires, warm and sustaining.

And sometimes she saw the Speerlies, enough of them to fill a thriving village. She was always amazed by how many of them there were, an entire race of people that sometimes she feared she’d only dreamed up. If the Phoenix lingered, then Rin could even catch fragments of conversations in a language she almost understood, could see glimpses of faces that she almost recognized.

They weren’t the ferocious beasts of Nikara lore. They weren’t the mindless warriors the Red Emperor had needed them to be and every subsequent regime had forced them to be. They loved and laughed and cried around their fires. They were people.

But every time, before Rin could sink into the memory of a heritage she didn’t have, she saw on the fading horizon boats sailing in from the Federation naval base on the mainland.

What happened next was a haze of colors, accumulated perspectives that shifted too fast for Rin to follow. Shouts, screams, movement. Rows and rows of Speerlies lined up on the beach, weapons in hand.

But it was never enough. To the Federation, they must have seemed savages, using sticks to fight gods, and the booms of cannon fire lit up the village as quickly as if someone had held a light to kindling.

Gas pellets launched from the tower ships with terribly innocent popping noises. Where they hit the ground they expelled huge, thick clouds of acrid yellow smoke.

Women fell. Children twitched. The warrior ranks broke. The gas did not kill immediately; its inventors were not so kind.

Then the butchering began. The Federation fired continuously and indiscriminately. Mugenese crossbows could shoot three bolts at a time, unleashing an unceasing barrage of metal that ripped open necks, skulls, limbs, hearts.

Spilled blood traced marble patterns into white sand. Bodies lay still where they fell. At dawn, the Federation generals marched to the shore, boots treading indifferently over crushed bodies, advancing to slam their flag into the bloodstained sand.

“We’ve got a problem,” Baji said.

Rin snapped back to attention. “What?”

“Take a look.”

She heard the sudden sound of jangling bells—a happy sound, utterly out of place in this ruined city. She pressed her face to a gap in the warehouse slats. A cloth dragon bobbed up and down through the crowd, held up on tent poles by dancers below. Dancers waving streamers and ribbons followed behind, accompanied by musicians and government officials lifted on bright red sedan chairs. Behind them was the crowd.

“You said it was a small ceremony,” Rin said. “Not a fucking parade.”

“It was quiet just an hour ago,” Unegen insisted.

“And now the whole township’s clustering in that square.” Baji squinted through the slats. “Are we still going by that ‘no civilian casualties’ rule?”

“Yes,” Chaghan said before Rin could answer.

“You’re no fun,” Baji said.

“Crowds make targeted assassinations easier,” Chaghan said. “It’s a better opportunity to get in close. Make your hit without being spotted, then filter out before his guards have time to react.”

Rin opened her mouth to say That’s still a lot of witnesses, but the withdrawal cramps hit her first. A wave of pain tore through her muscles; it started in her gut and flared out, so sudden that for a moment the world turned black, and all she could do was clutch her chest, gasping.