Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

Kitabı oku: «The Secret Key»

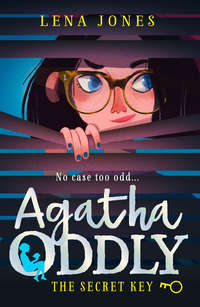

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollins Children’s Books in 2018

Published in this ebook edition in 2018

HarperCollins Children’s Books is a division of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd,

HarperCollins Publishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

The HarperCollins Children’s Books website address is

Text copyright © Tibor Jones 2018

Cover design © HarperCollinsPublishers 2018

Cover illustration by Alba Filella

Tibor Jones asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook onscreen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008211837

Ebook Edition © July 2018 ISBN: 9780008211844

Version: 2018-04-12

For Kika and Mylo

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

1. A Lesson in Chemistry

2. Hemlock and Foxglove

3. The Silver Tattoo

4. Run-in

5. The Red Slime

6. The Missing Plans

7. Breaking and Entering

8. Under the Weeping Tree

9. The Turning Eye

10. The Face of Tomorrow

11. A Vision of the Damned

12. The White Maze

13. Where No One Can Hear You Scream

14. Trapped

15. Epilogue

Acknowledgements

About the Publisher

‘This is the twelfth –’ the headmaster glances up from his notes – ‘no, let me correct that – the thirteenth time you’ve been in trouble this term, Agatha.’

We’re sitting in his office, the air sticky, and that’s not just because of the heatwave outside.

I look down at the floor. It’s true, and I don’t know what to say.

Dr Hargrave (Ronald Hargrave OBE, BPhil, MEd) likes to fill silences. He’s very good at that, and it’s best to wait until he’s done. He isn’t a doctor, as you and I think of them, but he likes to be called one. He has five liver spots in the shape of the constellation Cassiopeia on his forehead, and a steely glare, which I would say is a 4B on the eye-colour chart I have hanging in my bedroom.

He reads from his list:

‘One – you were found hiding in the ceiling space above the chemistry labs, because you believed Mr Stamp was stealing sulphuric acid to sell on eBay.’

This really happened – he was – but without evidence I had to drop my investigation. Plus, Dad grounded me.

‘Two – you tried to miss lessons by convincing the groundskeeper that you were an apprentice tree surgeon who needed to scale a tree near the boundary wall … and just so you could get out of school …’

I zone out. I’ve always found this easy – like switching channels on TV. If I want to watch something more interesting, I just imagine it. I call it my ‘Change Channel’ mechanism.

The headmaster’s desk is very shiny and if I look down I can see my own reflection in the caramel-coloured wood. I’m wearing my red beret – Dr Hargrave hasn’t even started lecturing me on this breach of uniform rules yet. My bob-cut hair frames my face, and my eyebrows are knitted together as though concentrating on his lecture. And, just like that, my reflection shimmers, shifts and becomes someone else. A small man in a hat and a bow tie looks back up at me. Smoothing out his moustache, he steps out of the desk, hops neatly to the floor and stands behind the headmaster.

‘How long do you think le docteur Hargrave will go on this time?’ he asks in a soft Belgian accent.

I zone back in to hear what my headmaster is saying now …

‘Four – you installed a listening device in the wall of the staffroom …’ – and then I glance back to where Hercule Poirot, famous detective, is looking at the clock.

‘Your headmaster has already been talking for twenty-two minutes.’ Poirot raises an eyebrow, as though daring me to do something about it. ‘He might break his record of twenty-seven, no?’

Actually, I reckon the headmaster is almost done – his stomach just rumbled, and it’s long after lunchtime. My eyes flicker around the room, details lighting up my mind like a pinball machine.

‘Twenty-four,’ I say out loud.

‘What?’ The headmaster looks up from his notes.

‘Nothing.’ I clear my throat.

Poirot nods in recognition – I have made my bet.

‘Are you listening to me, Agatha?’

‘Absolutely, sir. You were saying that impersonating a health inspector is a criminal offence.’

‘Yes, I was. Do you not take that seriously, Agatha?’

I nod seriously. ‘I do, Headmaster. I was just starting to worry.’

‘Worry? Worry about what?’ The headmaster’s eyebrows furrow.

‘That you’d be late for lunch with your wife.’

A look of confusion creases his face at the change of tack. ‘My … wife?’

‘Yes. You’re wearing a very nice shirt, sir. And aftershave. And I couldn’t help notice the box of chocolates on your table, clearly a gift for a lady …’ I smile, pleased with my investigatory skills.

‘Aha, yes,’ he splutters, ‘my wife.’ He looks at the clock on his wall. The words hover in the air like fireflies. ‘As you were saying, I’m going to be late for lunch … with my wife.’

‘Well, sir, I wouldn’t want to make you late,’ I say.

Dr Hargrave stands up, brushing invisible crumbs from his suit. ‘Yes. I’d better get going.’ He glances around, as though looking for the exit. ‘As for you, Agatha, I would advise you to think about … um … everything I’ve said.’

‘I will, sir.’

Dr Hargrave seems to be sweating as he shows me to the door where Poirot stands, smiling with approval. Poirot looks at his pocket watch.

‘Twenty-four minutes – you were right, mon amie.’

I smile as Dr Hargrave opens the door for me.

‘Bien sûr,’ I say.

‘What was that?’ asks the headmaster.

‘I said, enjoy your lunch, sir.’

He presses his lips together, as though holding something back, then mutters – ‘Be careful, Agatha Oddlow. Be very careful.’

Liam Lau, my best friend, is pacing the corridor outside when I come out of the office. He turns to face me, his face all scrunched-up-serious. It takes me a moment to remember why. Ah yes – Liam knew I was in trouble and thinks I’m going to be expelled. In fact, Liam has been expecting my expulsion from St Regis since the day we met – only this time he’s sure that this latest adventure will be my last. Wanting to draw out the suspense, I pull a sad face.

Liam covers his face with his hands. ‘What did I tell you?’ he wails. ‘Who will I eat lunch with now?’

It’s true, Liam and I do eat lunch together – every day, in fact – at least whenever we cross over after lessons. We sit on ‘Exile Island’ – the table in the refectory where all the weird kids sit.

‘Liam …’ I start.

‘I know I shouldn’t moan,’ he groans.

‘Liam …’

‘Expelled …’ He groans again. ‘Oh, Agatha, maybe we can get him to reconsider? Maybe if we get your dad to write a letter—’

‘Liam!’ I shake him by the shoulders. Finally, he stops to listen.

‘I’m not going to be expelled,’ I say again.

He freezes. ‘You’re …’

‘Not. E-x-p-e-l-l-e-d.’ I spell the letters out, one by one, and examine my nails, painted forest green and bitten to the quick.

A smile smooths the worry lines from Liam’s face. He grabs me and gives me a massive hug. ‘What did Dr Hargrave say?’

I give him a sideways glance from under a fallen strand of hair. ‘I’ll tell you all about it. Come on – or we’re going to be late for chemistry.’

‘That’s not a superpower.’

‘I’m just saying – not getting expelled would be a pretty useful superpower.’

‘But superpowers are stuff like invisibility, or levitation. “Not getting expelled” is just what normal people do.’

The school day is over, and Liam and I are meeting back in our form room.

‘Normal people don’t have as much fun as I do.’

Liam imitates the school librarian, looking disapprovingly over his glasses, and I can’t help but smile. He always manages to cheer me up. He never judges me for Changing Channel, or for talking to people who aren’t there. ‘So, did you find any more clues about the caretaker?’ he asks.

I shrug. That’s why I was in trouble in the head’s office in the first place – for dressing as a health inspector to check up on the caretaker who has been acting suspiciously for weeks. I’ve wanted to be a detective since I was young and love putting on a disguise. Mum always encouraged me. She liked setting me trails of clues to follow and solve. But, as you know, after several, ahem, incidents, I’ve been – well, I’ve been banned by the headmaster from doing anything that might be called ‘snooping on innocent people’. Liam isn’t as passionate about being a detective as I am, but he does enjoy solving puzzles and cracking codes. That’s why we’ve set up the Oddlow Agency (no ‘detective’ in the title, to avoid annoying the headmaster).

‘So shall we start the meeting, Agatha?’

‘Yes,’ I nod. ‘I’ll have to be quick, though; I need to get some stuff for dinner.’

‘Haute cuisine? Cordon bleu?’ Liam puts on an exaggerated French accent like I sometimes do when Poirot is with me.

‘Oui. That’s the idea, anyway.’

He nods seriously and opens the brand-new record book of Oddlow Investigations. My name is so often abused by other people (Oddly, Oddball, Odd Socks) that I’ve made it a part of my motto – ‘No Case Too Odd’. Unfortunately, the Oddlow Agency hasn’t been employed for a case yet. Still, that’s no reason not to keep proper records.

‘First order of business,’ I begin, ‘is the design of the insignia to be used on all official correspondence, business cards and rubber stamps. Any thoughts?’

Liam ponders for a second.

‘What about a lion … holding a magnifying glass!’

Really? I give him a hard stare and change the subject. It doesn’t sound very imaginative to me. ‘Why don’t we think about stationery later? We could practise taking identification notes?’

‘Sure. But you’ll have to tell me what identification notes are.’ He grins.

I look across at him and smile. ‘Identification notes are important facts about everyone. I write them for all sorts of people – anyone who might be important in an investigation.’ I shrug. ‘They help me remember what they looked like, how they dressed, what perfume they had on … that kind of thing.’

‘OK, I reckon I can do that.’ Liam nods. ‘Let’s start by giving it a go for each other.’

‘OK, so take your notebook and write three identifying things about me. Things that are unusual – that make me stand out. I’ll do the same for you.’

We put our heads down and scribble for a few minutes, then swap notebooks. Thoughtfully, I chew on my pencil as I hand them over.

My identification notes for Liam Lau –

1. Liam used to be smaller than me by a couple of inches, but has recently had a growth spurt that brings us level pegging.

2. He has black-rimmed glasses and dark hair, which is always immaculate. ‘Geek chic’ would describe his look.

3. He’s inseparable from Agatha Oddlow.

Liam’s identification notes for me –

1. Agatha is thirteen years old, 5 ft 2 (ish?). She has chestnut-brown hair worn in a bob.

2. She likes wearing vintage clothes – floral dresses, trench coats, DMs. So many trench coats. She’s often writing in a notebook.

3. Always hanging out with Liam Lau.

I’m about to say that my hair is dark brown, not chestnut, when someone bursts loudly into the classroom.

‘We can use this room, it’s just Oddball and Boy Wonder in here,’ they say.

I know immediately whose voice it is before I turn round – Sarah Rathbone, one of the three CCs, and she’s got the other two with her – Ruth Masters and Brianna Pike. They say that CC stands for Chic Clique, but everyone else says it stands for Carbon Copies. With their identically blonde hair, manicured nails and primped and preened appearances, they stand for everything St Regis is about. The school is full of the rich and beautiful like them, and making the rest of us feel unpopular is what they’re best at.

Some identification notes, for telling one CC from another –

1. Sarah Rathbone – If the other two are copies, Sarah is the original. The jewellery she wears has real diamonds, but it’s small and tasteful.

2. Ruth Masters – Second-in-command, Ruth is ruder than Sarah, which is saying something. Her dad works in PR, and Ruth is just as conscious of her public image, carefully managing who the CCs talk to and who they avoid.

3. Brianna Pike – Brianna is Sarah’s other henchwoman. She plays with her hair a lot and spends all day posting pictures of herself pouting on social media.

I face Sarah, head on. ‘I’m afraid we’re using this room,’ I say.

‘Using it for what?’ Sarah sneers. ‘Making detective notes with your little friend?’

Brianna approaches me. She draws her shoulders back and swings her blonde hair like a weapon. ‘Move.’

‘But we’re in the middle of something,’ I say.

‘We’re in the middle of something?’ Ruth sing-songs back at me. ‘Well, get in the middle of this – SCRAT.’ She brings her face up-close-and-personal and I automatically spring back. She picks up the book I’m reading from the table – Poisonous Plants of the British Isles – and shoves it into my chest.

‘Enough messing around,’ Brianna joins in, ‘get out, Agatha. Get going.’ She pushes my shoulder.

I brush my blazer as though some dirt has landed there. ‘Come on, Liam,’ I say, gathering my things. ‘We’re outnumbered.’ And then I mutter under my breath, ‘Physically, if not mentally.’

By the time the CCs realise they’ve been insulted, we’ve already left the room. The door slams behind us. I sigh, letting my frustration show.

‘You OK, Aggie?’

‘Yes … thanks, Liam.’ I shrug. Sometimes I hate St Regis more than anywhere in the world. My first school, Meadowfield Primary, was so different. The buildings might have been falling down and there was never enough money for new books, but it had been bright and friendly, and the teachers had encouraged all of us just to get along. I had a nickname there – The Brain – which hadn’t been a bad thing. It was a dumb nickname, but secretly I had liked it. At Meadowfield, being brainy was OK. When nobody else knew the answer to a question, they’d turn to me. Then had come the scholarship to St Regis that my teacher had put me forward for. I almost hadn’t shown it to Dad. When he saw the letter, he’d said it would be silly not to at least take the test. He’d been right, hadn’t he? There was nothing to lose. Even if they offered me a place, I could still turn it down, right? And they probably wouldn’t offer me a place anyway, would they?

I took the test.

I won the scholarship.

Dad sent a letter back, saying I would accept, starting in September.

I had been excited about going to a prestigious school at first. My new school had more money floating around than Meadowfield could have ever dreamed of. New computers, new classrooms, spotless walls and carpets. But in this place of shiny things, it was me who ended up seeming shabby. It didn’t matter whether I was brainy. In fact, it didn’t matter whether I was kind or funny or whatever else might have made me the person I was. I just didn’t fit, until I met Liam …

I’d been sitting in the canteen (or refectory, as they preferred) of St Regis, eating lunch, when I pulled the Sunday Times from my satchel and started trying to do the cryptic crossword.

13 down – Calling for business meeting, talker gets excited.

‘Perhaps “calling” means a telephone call.’ A voice came from across the table. I jumped – I hadn’t realised that I’d been thinking out loud. I looked up and saw a boy my own age who I recognised from class. His name was Liam Lau. I don’t think I’d heard him speak once, except to answer ‘present’ when register was called.

‘Sorry, did I startle you?’

‘No, I … I just didn’t realise I was talking to myself.’

He smiled. ‘Do you do that often?’

‘Maybe. Sometimes.’

‘Me too.’ He nodded, grinning. ‘They say it’s the first sign of madness.’

‘Hmm … Maybe you’re right about “calling” being a telephone call.’ I said. Then, as though my brain had suddenly decided to co-operate – ‘Oh, and what if “excite” means “jumble” – there might be an anagram in there?’

‘Yes, that sounds good … Hmm, what about “meeting talker”?’ Liam said. ‘That’s the right number of letters.’

We both stared at the letters M E E T I N G T A L K E R for a long moment. Then, together, we both shouted –

‘Telemarketing!’

I was grinning as I took up my pen and put the answer in.

‘Agatha …’

Liam’s voice shakes me out of the memory. Here we are, almost a year later. I’m still a social outcast, but I have Liam as a friend. I look at him. ‘Yes?’

‘Promise me something?’

‘What?’ I ask.

‘Try not to get expelled tomorrow?’

I roll my eyes. ‘I promise.’

He grins. ‘Come on, then – you can walk me to the bus stop.’

I’ve just finished liquidising a pile of vegetables when Dad walks into the kitchen, begrimed with mud and smelling of manure. I’d forgotten my tiredness in the excitement of making something new.

‘What on earth are you doing, Aggie?’

‘Making dinner,’ I say.

‘With all the green mush, I thought it might be some kind of science experiment,’ he laughs.

I sigh – Dad can be soooo closed-minded sometimes. He isn’t a bad cook, but he isn’t a very good one, either. I often make dinner for the two of us, but it’s usually one of his favourites – something easy, like sausages and mash or beans on toast. Who can blame me for wanting to try something different for a change? I’d found a dog-eared copy of Escoffier’s Le Guide Culinaire from a bookshop on the Charing Cross Road, and then spent an evening trying to decode his instructions from the original French. Dad looks over at the wreckage, shaking his head, and trudges off to get clean.

Dad – Rufus to everyone but me – has been a Royal Park warden since he left school at sixteen. He’s worked his way up to the position of head warden of Hyde Park, so we live in Groundskeeper’s Cottage. Still, even though Dad’s in charge, he refuses to let others do all the dirty work and is never happier than when he’s got his sleeves rolled up and is getting his hands dirty. He reappears in a fresh shirt, smelling strongly of coal-tar soap, which is an improvement from the manure. He looks over at the food I’m making, stroking his gingery-blond beard.

‘What … is it?’

‘Vegetable mousse, with fillets of trout, decked with prawns and chopped chervil.’

‘Looks quite fancy, love.’

‘Just try it – you’ll never know if you like it otherwise.’

Dad shrugs and sits down.

I’ve been saving up for weeks for the ingredients. Dad gives me pocket money in exchange for a couple of hours shovelling compost at the weekend so it’s been a hard earn. But it’s worth it – everyone should have a chance to try the better things in life, shouldn’t they? Dad reaches for his fork, staring at the plate. He searches for something diplomatic to say, and fails. ‘It’s not very English.’

I smile.

‘Poirot says something like, “the English do not have a cuisine, they only have the food,”’ I recalled.

He groans at the mention of my favourite detective. I go on about Hercule Poirot so much that Agatha Christie’s great detective is a bit of a sore spot for Dad.

‘You and those books, Agatha! Not everything that Poirot says is gospel, you know.’

I ignore this last comment and plonk a plate of the fish and veg medley in front of him. He takes a fork of everything, and I do the same.

‘Bon appetit!’ I smile, and we eat together.

Something is wrong. Something is very wrong.

I look to Dad, and I’m impressed by how long he manages to keep a straight face.

Something awful is happening to my taste buds. I can’t bring myself to swallow for a long moment, and then I force it down, gagging.

‘I may have … mistranslated.’

Dad swallows, eyes watering.

‘Might I have a glass of water, please?’

When the last of the mousse has been scraped into the bin, we go off to buy fish and chips. I decide not to paraphrase Poirot’s thoughts on fish and chips, that ‘when it is cold and dark and there is nothing else to eat, it is passable’. I don’t think Dad would be amused and, besides, I really like fish and chips.

After carrying them back from the shop in their paper parcels, our stomachs rumbling, we eat in happy silence. I savour the crisp batter, the soft flakes of fish, the salty, comforting chips. For once, I have to admit that Poirot might have been wrong about something.

While we eat, Dad asks about my day, but I don’t feel like talking about school and the CCs, or the headmaster, or about how I’d zoned out in chemistry class, so I ask about his instead.

‘So are the mixed borders doing well this year?’

‘Not bad,’ he grunts.

I think of the book I’m reading at the moment.

‘And do you grow digitalis?’

‘If you mean foxgloves, then there are patches of them down by the Serpentine Bridge.’

‘What about aconitum?’ I eat a chip, not looking Dad in the eye.

‘Monkshood? You know a lot of Latin names … Yes, I think there’s some in the meadow, but I wouldn’t cultivate it. It’s good for the bees, though.’

‘Ah … what about belladonna?’

‘Belladonna …’ His face darkens, making a connection. ‘Foxglove, aconitum, belladonna … Agatha, are you only interested in poisonous plants?’

I blush a little. Found out! Poisonous Plants of the British Isles is sitting in my school satchel as we speak.

‘I’m just curious.’ Deep breath.

‘I know that, love, I do. But I worry about you sometimes. I worry about this … morbid fascination. I worry that you’re not living in the real world.’

I sigh – this is not a new discussion. Dad loves to talk about the REAL WORLD, as though it’s a place I’ve never been to. Dad worries that I’m a fantasist – that I’m only interested in books about violence and murder. He’s right, of course.

‘I’ll do the washing-up,’ I say, quickly changing the subject. Then I look over at the sieves, pans and countless bowls that I’ve used in my culinary disaster. Perhaps not.

‘My turn, Agatha,’ says Dad. ‘You get an early night – you look tired.’

‘Thanks.’ I hug him, smelling coal-tar soap and his ironed shirt, then run up the stairs to bed.

When we’d first moved into Groundskeeper’s Cottage, I chose the attic for my bedroom. Mum had said it was the perfect room for me – somewhere high up, where I could be the lookout. Like a crow’s nest on a ship. I was only six then, and Mum had still been alive. Before that, we’d squeezed into a tiny flat in North London, and Dad had ridden his bike down to Hyde Park every day. He’d been a junior gardener when I’d been born, still learning how to do his job. The little flat was always full of green things – tomato plants on the windowsills, orchids in the bathroom among the bottles of shower gel and shampoo …

The attic has a sloping ceiling and a skylight that is right above my bed so, on a clear night, I can see the stars. Sometimes I draw their positions on the glass with a white pen – Ursa Major, Orion, the Pleiades – and watch as they shift through the night.

The floorboards are covered with a colourful rug to keep my toes warm on cold mornings. We don’t have central heating, and the house is draughty, but in mid-July it’s always warm. It’s been scorching today, so I go up on my tiptoes and open the skylight to let some cool air in. My clothes hang on two freestanding rails. Dad is saving to get me a proper wardrobe, but I quite like having my clothes on display.

On one wall there’s a Breakfast at Tiffany’s poster with Audrey Hepburn posing in her black dress. Next to her is the model Lulu. There’s also a large photo of Agatha Christie hanging over my bed, which Liam gave me for my birthday. On the other is a map of London … Everything I need to look at.

My room isn’t messy. At least, I don’t think it is, even if Dad disagrees. It’s simply that I have a lot of things, and not much room to fit them in. So the room is cluttered with vinyl records, with books, with a porcelain bust of Queen Victoria that I found in a skip. Every so often, Dad makes me clear it up.

And so, I try to tidy now. But with so little space it just looks like the room has been stirred with a giant spoon.

I take the heavy copy of Le Guide Culinaire and place it on my bookshelf, which takes up one wall of the room. I sigh – what a waste of time. What a waste of a day.

I run my hand along the spines of the green and gold-embossed editions – the mysteries of Poirot, Miss Marple, and Tommy and Tuppence – the complete works of Agatha Christie, who my mum named me after. She’d got me to read them because I liked solving puzzles, but said I should think about real puzzles, not just word searches and numbers. When I’d asked what she meant, she had said –

‘Everybody is a puzzle, Agatha. Everyone in the street has their own story, their own reasons for being the way they are, their own secrets. Those are the really important puzzles.’

I feel hot tears prick the back of my eyes at the thought that she’s not actually here any more.

‘I got called in front of the headmaster today …’ I say out loud. ‘But it was OK – he just let me off with a warning.’ I continue, tidying up some clothes. I do this sometimes. Tell Mum about my day.

I change from my school uniform into my pyjamas, hanging everything on the rails and placing my red beret in its box. What to wear tomorrow? I choose a silk scarf of Mum’s, a beautiful red floral Chinese one. I love pairing Mum’s old clothes with items I’ve picked up at jumble sales and charity shops, though some of them are too precious to wear out of the house.

Next, I go over to my desk in the corner and unearth my laptop, which is buried under a pile of clothes. I switch it on and log in. People at school think I don’t use social media, but I do. I might read a paper copy of The Times instead of scrolling down my phone, and write my notes with a pen. But I’m more interested in technology than they’d know. You can find out so much about people by looking at what they put online. Of course, I don’t have a profile under my own name. No – online, my name is Felicity Lemon.

Nobody seems to have noticed that Felicity isn’t real. Several people from school have accepted my friend requests, including all three of the CCs. None of them have realised that ‘Felicity Lemon’ is the name of Hercule Poirot’s secretary, or that my profile photo is a 1960s snap of French singer Françoise Hardy.

I scroll through Felicity’s feed, which seems to be endless pictures of Sarah Rathbone, Ruth Masters and Brianna Pike. They must have flown out to somewhere in Europe for a mini-break over half-term. They pose on sunloungers, dangle their feet in a hotel swimming pool and sit on the prow of a boat, hair blowing behind them like a shampoo commercial. Despite myself, I feel a twinge of jealousy and put the lid down.

Rummaging through my satchel, I take out the notebook that I started earlier in the day. I put it by my bed with my fountain pen, in case inspiration strikes in the night – that’s what a good detective does: they note down everything, because they never know what tiny detail might be the key to cracking a case.

Most of my notebooks have a black cover, but some of them are red – these are the ones about Mum – all twenty-two of them. They have their own place on a high shelf. My notes are in-depth – from where she used to get her hair cut to who she mixed with at the neighbourhood allotments. Every little detail. I don’t want to forget a single thing.

I look over at Mum’s picture in its frame on my bedside table. She’s balanced on her bike, half smiling, one foot on the ground. She’s wearing big sunglasses, a crêpe skirt, a floppy hat and a kind smile. There’s a stack of books strapped to the bike above the back wheel. The police had blamed the books for her losing control of her bike that day – but Mum always had a pile of books like that. I don’t believe that was the real cause of her accident. That’s not why Mum died. Something else had to be the reason.

I climb into bed and pull the sheet over me, then take a last look at the photograph.

A lump rises in my throat. ‘Night, Mum,’ I say, as I turn out the light.

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.