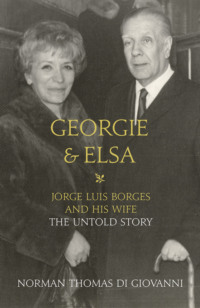

Kitabı oku: «Georgie and Elsa: Jorge Luis Borges and His Wife: The Untold Story», sayfa 2

One version of Elsa’s reappearance on the matrimonial scene tells that Borges’s mother learned that Elsa was now a widow and urged her son to contact her. A meeting was arranged via Elsa’s sister Alicia. Elsa showed Borges a ring he had given her years before; he was moved that she had kept it. Borges later showed Elsa a photograph of her that he had kept between the leaves of a book; doña Leonor told Elsa that for years he looked at it every night before going to bed. All this is too pat and smacks too much of a fairy tale to ring true.

Exactly when these events were supposed to be taking place we do not know. There was some mention of Elsa’s qualifications, as she knew no English. A second version of the story is that another of Borges’s old flames, Margarita Guerrero, was mooted as a possible wife. This too seems to me an absurdity. Margot, as she was known, was a striking beauty, tall, elegant, and worldly. All the things Elsa was not. Was Margot one more of Borges’s – or his mother’s – preposterous fancies?

Eventually Borges chose Elsa, proposed to her, and she accepted. Again there are no dates for any of this. Plans were made for the registry and the church ceremonies. Now it was time for Elsa – unknown in Buenos Aires literary or social circles – to be paraded for inspection. As was to be expected, doña Leonor’s circle of upper-class women, snobs to the last one, sniffed and probed and found Elsa wanting. It was an ocular inquisition. She proved frumpish, unsophisticated, and lacking in looks. It is true that even with her mouth shut tight Elsa was loud. When she laughed her cackle turned shrill and went on far too long. But she would have had little to laugh about at these gatherings; Elsa knew what was taking place and in the end she got her own back by snubbing the lot of this smart set who had arranged a party for the newlyweds on the eve of their departure for the United States. Elsa simply did not show up, leaving Georgie to attend the gathering on his own.

Within a week the couple set off on their great adventure, arriving in Boston on 29 September 1967.

3. Off on the Wrong Foot

At Harvard, Elsa was immediately plunged into the thick of an academic community and a life that she could not have foreseen and that Georgie could not have prepared her for. This was not the froth of upper-class, pseudo-intellectual Buenos Aires ladies who had informed a large part of Borges’s existence in Argentina. Elsa could deal with such people by ignoring them and falling back on her own family and friends.

Here in Cambridge, Borges’s colleagues were all each other’s close friends as well as being highly professional world-class Hispanic scholars. Borges had made the acquaintance of some of these men and women during a visit to Harvard with his mother in 1961 or 1962, when he spent a semester at the University of Texas. Others were old friends and associates from earlier years together in Buenos Aires.

Juan Marichal, who had been at Harvard since 1949, was chairman of the Romance Languages and Literatures Department at the time of Borges’s appointment to the Norton lectureship. Recognized as one of the most important intellectuals of the Spanish diaspora following the civil war, Marichal was a historian, literary critic, and essayist. He spent ten years rescuing and assembling the scattered and suppressed works of Manuel Azaña, a leading politican and victim of the Franco dictatorship. Marichal’s wife was Solita Salinas, daughter of the poet Pedro Salinas – whose writings Marichal also edited – and sister of the Madrid publisher Jaime Salinas.

It so happened that one of the late Pedro Salinas’s closest friends and associates was Jorge Guillén, whom Borges regarded as the finest living poet of the Spanish language. In retirement, Guillén resided in Cambridge with his wife Irene and his daughter Teresa, who was married to Stephen Gilman, also a Harvard professor. Gilman was a Hispanist who wrote, among other books, specialist studies of classics like the Cid and the Lazarillo de Tormes, the theatre of Lope de Vega, the fifteenth-century La Celestina, its author Fernando de Rojas, and the nineteenth-century novelist Benito Pérez Galdós.

Between all these people the links were tight. To occupy his time and keep from falling into boredom, in addition to his six public lectures Borges in his first term at Harvard gave a small class on Argentine writers. Who was it who volunteered to pick him up from his flat and shepherd him to his classroom, where they sat in on his lectures? Teresa Gilman and Irene Guillén.

Also at Harvard was the unassuming Raimundo Lida, whom Borges had known since the early 1930s and the founding of Sur. Lida had then served as its managing editor. From 1953 he had been at Harvard, where he preceded Marichal as department chairman. Lida was a philologist, a philosopher of language, and an expert in the Romance philology of the Spanish Golden Age. He had been born into a Yiddish-speaking family in a part of the Austro-Hungarian empire that is now Ukraine. When only a few months old he emigrated with his family to Buenos Aires. His wife was Denah Lida, a professor at nearby Brandeis University, where her specialities were Ladino and Sephardic languages. She too wrote a book on Pérez Galdós. It was Lida who retrieved Borges and Elsa from the airport on their arrival and helped set them up in their first flat.

Joan Alonso, the widow of another scholar known to Borges, also formed part of the preceding circle. Amado Alonso had been born in Spain, but emigrated to Argentina before he finally established himself at Harvard. He had been a distinguished philologist, linguist, and literary critic. Joan, who was not of Spanish origin, had at some point become a friend of Borges’s mother, with whom she carried on a correspondence and reported to doña Leonor on Borges and Elsa’s comings and goings in Cambridge.

There was another Argentine well known to Borges who taught at Harvard at this time – the writer, literary critic, and novelist Enrique Anderson Imbert. His stories, branded micro-cuentos, were much admired in the Argentine at the time for their blend of fantasy and magical realism. Borges loathed and looked down on Anderson Imbert, partly from envy of the latter’s success and partly because Borges disliked being linked to Anderson through the kind of writing they both exercised. Consequently at Cambridge they hardly ever met.

Such then was the company Elsa was expected to keep. It was not her lack of English that turned out to be the problem; all these people spoke Spanish. Rather, it was her lack of intellect. Borges, who should have foreseen this, was simply oblivious of the problem. As ever, he was locked in self-absorption, in his own private, hermetic existence. He made a feeble attempt to interest Elsa in English by applying to her one of his pet ideas – that of learning a language through the study of its poetry. He saddled her with a favourite text, Robert Louis Stevenson’s brief ‘Requiem’:

Under the wide and starry sky

Dig the grave and let me lie:

Glad did I live and gladly die,

And I laid me down with a will.

This be the verse you ’grave for me:

Here he lies where he long’d to be;

Home is the sailor, home from the sea,

And the hunter home from the hill.

But Elsa had no interest in English verse; Borges should have known the experiment was doomed to fail.

On one occasion, as Borges told it, Elsa baulked and refused to attend a party given by some of his Harvard colleagues when she learned that her husband was not to be the guest of honour. But Elsa was cleverer than Borges gave her credit for. This was her way of extricating herself from a class of people she simply could not deal with, allowing her to escape from the real or fancied humiliation she felt in their company. Consequently, social engagements and invitations dried up, and out of forced loyalty to his wife Borges was stuck at home, having to settle for a kind of bleak exile.

4. The Norton Lectureship

As Elsa had announced, she was going to be in Cambridge on a honeymoon. She can’t have known a thing about the Charles Eliot Norton Professorship in Poetry or about any of the previous incumbents of the chair.

The lectureship had been founded in 1925 in memory of Harvard’s first fine arts professor, who taught the subject from 1874 to 1898. The term poetry was interpreted in the widest sense to include musicians, painters, sculptors, and architects as well as poets, scholars, and writers. The incumbents are in residence throughout their tenure and are expected to deliver at least six lectures.

The series was inaugurated in 1926-27 by the venerable classicist Gilbert Murray. Among subsequent figures have been T.S. Eliot, Robert Frost, Igor Stravinsky, Aaron Copland, E.E. Cummings (who called his talks ‘nonlectures’ and warned from the outset that ‘I haven’t the remotest intention of posing as a lecturer.’), Herbert Read, Edwin Muir, Ben Shahn, Jorge Guillén, Pier Luigi Nervi, and Cecil Day Lewis. The 1940-41 lectures were delivered by Pedro Henríquez Ureña, the man who first drew Georgie and Elsa together, but it is unlikely that anyone would have brought this to Elsa’s attention.

Elsa found fault with the living quarters obtained for her by the university but soon located a flat to her liking in Concord Avenue. Borges had been provided with an office in Radcliffe’s Hilles Library, which he seldom used, and was offered the services of a secretary, John Murchison, an Anglo-Argentine graduate student.

In his lectures, Borges sat behind a table, stiff and upright, always insisting on having a glass of water in front of him, which he would reach out to touch to make sure it was the right distance from his hand. He refused to begin without it but rarely had recourse to it. Being blind he used no papers or notes. He had a large round pocket watch attached by a chain to his left lapel and would start by lifting the dial right up to his eye. That much he could make out. He knew he had to speak, hopefully without referring to the watch again, for at least fifty minutes.

He always dressed in a grey suit of a decidedly out-of-date cut. His necktie, which he referred to as ‘a trick tie’, was one of those ready-made affairs that he could clip together himself under his collar and not have to bother to knot. His stiffness and his old-fashioned clothes lent him an air of formality that he would not have been aware of. At the same time, unable to see or gauge his audience, he exuded unworldliness, vulnerability, and perhaps a hint of pathos. Everyone seemed to be aware that they were about to be addressed by a lone blind man. As he sat waiting while a technician tested and adjusted a microphone, Borges would cradle one of his hands in front of him into the palm of the other.

Then he would begin. His spoken English was very good. He might stutter occasionally out of nerves and he had a bit of a Scottish burr which required getting used to. He did not have a loud register and was not good at projecting his voice, but this only made people listen more attentively. Out of fear of missing a word, his audiences kept exceptionally quiet.

When his nerves settled he would toss out the odd crowd-pleaser so as to get his listeners to warm to him.‘Of course, I’m decidedly old-fashioned,’ he would say, and they would howl with delight. Here was a writer worshipped for being the last word in avant-garde and he was claiming just the opposite. He would mention and quote from writers nobody read any more – De Quincey, Wells, Stevenson, Chesterton – suddenly giving them, in his audience’s view, a new allure, a new promise. His reading had stopped around 1930 and he knew little or nothing of contemporary writers. This was another aspect of his appealing old-fashionedness – he made the past new, revisitable, and alive again.

It was uncanny how his tricks worked. His talks were simple, quite personal, and peppered with anecdotes (‘My memory carries me back to a certain evening some sixty years ago, to my father’s library in Buenos Aires’) and idiosyncrasies. He frequently went off on asides – etymologies were one of his favourites. On days when he felt unsure of himself or of his audience he laid on the self-deprecation and, tongue in cheek, would belittle his own literary creation, which he spoke of as ‘my so-called work’. Self-effacement was another of his tools. When he spoke of his life in writing, he would add, ‘or trying my hand at writing’. He was never relaxed behind his table, and the public saw this, which put them on his side.

He could charm with his bookishness and his harmless ‘out-of-the-way learning’, as he called it. He quoted Shakespeare or Keats or Wordsworth seemingly at will and would flatter his listeners with his undisguised partisanship. He relished speaking of ‘Literature – that is, English literature.’ He fascinated his audience with his keen interest in remote subjects like Old English and Old Norse.

At the same time, his talks were not without their flaws. He misquoted, sometimes over-indulged in the self-effacement department, and often jumped from one subject to another without providing adequate transitions. The public never noticed or seemed to care. They were in the presence of Borges.

The truth is that audiences flocked to his lectures. Whether at Harvard, or the Poetry Center of New York’s YM-YWHA, or countless classrooms across America, or the lowliest ill-lit, draughty, dilapidated auditorium of lost towns of his native pampa, Borges always packed them in. So many unexpected listeners turned up for his inaugural Norton lecture that the venue had to be shifted from the Fogg Museum and across Harvard Yard to the Sanders Theatre in rambling Memorial Hall.

Borges’s first talk at Harvard, entitled ‘The Riddle of Poetry’, was given on 24 October 1967. The series of six he called This Craft of Verse.

5. Meeting Borges and Setting Out with a Master

In the late autumn of 1967, while Borges was mentally preparing his third lecture and Georgie and Elsa were nursing their marital bliss, I innocently entered their lives.

It was all a matter of accidents, coincidences, and luck. I’d been reading bits of Latin American poets, got hooked on Borges, and decided to repair to Schoenhof’s foreign bookshop, in Harvard Square, for a copy of his collected poems in Spanish. When the clerk handed me the book he casually announced that Borges would be speaking there at Harvard the next week. I had no inkling Borges might be anywhere but in his own country.

I was in Memorial Hall that next week – it was 15 November – to hear his second Norton Lecture, a talk on ‘The Metaphor’. Borges’s spoken English immediately struck me, as did his views on his chosen subject. A week passed, and I sat down and wrote to him. My letter said that I was interested in producing a volume of his poems in English translation along the lines of the fifty poems from Jorge Guillén’s Cántico that I had published two years before. It was all a stab in the dark. I had no idea of the regard in which Borges held Guillén, nor had I any idea that Guillén’s daughter Teresa and wife Irene were attending Borges’s classes on Argentine writers.

Within a week I had a reply from John Murchison, Borges’s Harvard secretary, to tell me that Borges was pleased with my suggestion and ‘would be delighted to have you phone him at his home …’

A few days later I phoned. A woman answered, it was Elsa, but as I was unused to Argentine Spanish I thought hers was an Italian voice. She seemed to be speaking Italian when she called out, ‘Georgie’. This was my introduction to the accent and intonation of rapid-fire porteño Spanish.

Borges answered, I identified myself, and he was at once lively and interested. He spoke in a clipped voice, with an English accent, and asked me right off what edition of the poems I had. When I told him, he said, ‘Well, that’s not the latest.’

‘Oh, dear.’

‘That’s of no consequence,’ he said. ‘I don’t know if the new edition is even in print yet. I have added a few new poems – all short ones. I have them all memorized.’

Then he asked would I come today. What time? Six o’clock. He gave me the address and repeated the apartment number twice. Eagerly, he also asked me to bring some of the translations. I told him he had misunderstood; I hadn’t any translations yet but would be commissioning them.

‘Well, come and we’ll talk,’ he said, his enthusiasm undiminished.

It did not occur to me then that Borges would have asked Teresa Gilman, or perhaps even Guillén himself, about me. I know in their loyalty they would have given me a warm report. Elsa would have invested this train of events with prophetic significance, calling it fate. But predetermination is not one of my beliefs; what was taking place at breakneck speed I knew to be just dumb luck.

That evening, for a couple of hours, Borges and I sat at a wooden table opposite each other on the benches of the flat’s old-fashioned built-in breakfast nook. We discussed the planned volume in general terms and then went over some specific lines in a couple of poems I had been tinkering with in English translation.

The present book – the story I am trying to tell here – is about Georgie and Elsa. I want it to be a book about two married people, one of whom happens only incidentally to be a famous writer. My interest is strictly in them, not in literary criticism. And yet it was the work that Borges and I were embarking on that was the glue that held the three of us together. Perhaps, then – as an aside – the briefest, pedantry-free description of our daily enterprise would not be out of place.

I first read through his poems – they dated from 1923 to 1967 – and then joined him to hammer out a suitable broad selection. I brought notes, and while Borges would volunteer information about this or that poem I would scribble down jottings that might later prove useful to a prospective translator. Our views of what to include or exclude in a volume of a hundred poems rarely failed to coincide. Next I would take to our meetings a literal line-by-line handwritten draft of the poems, each of which we discussed at length. As Borges was blind, I read him one line at a time and added changes and corrections as he guided me.

There was a long history of visual abnormalities running through the male side of Borges’s family. His father before him had lost his sight, and from his early years Borges was severely myopic. His vision had gradually deteriorated down the years until around 1955, when he could no longer read. When I met him he was able to distinguish the colour yellow as a luminous patch and so had a preference for yellow neckties. This too left him in time. When our books were published he would hold the title page up close to his face and make out the large letters. I noticed that he saw outlines better in bright light, and that his psychological state was a factor as well. This blindness worked to the advantage of our translations, since everything had to be read to him and demanded his strict attention.

For the rest, the task was one of lengthy administrative duties. On my own I began to match up poems and translators, beginning with some of the same poets who had assisted me in the Guillén volume. This time I included myself among the translators. I corresponded with each contributor, criticized their English versions when they came back to me (often toing and froing with them several times per poem), and generally kept my stable of writers working. When I felt a poem was finished, I read it to Borges for a final nod of approval.

Other administrative duties consisted of raising funds to pay the translators and, most important of all, finding a publisher. It was a whirlwind of activity. I first met Borges at his flat on 4 December 1967. Before that month was out I had landed my publisher, Seymour Lawrence, and Borges had written to his, Carlos Frías, in Buenos Aires – dictating the letter to me – to secure English-language rights. I was amused and flattered when in the letter he referred to me as ‘the onlie begetter of this generous enterprise’. He quickly explained that Frías was also a professor of English literature, so the Shakespeare link would not be wasted on him.

Work on these selected poems began in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and they were three years in the making before being finished in Buenos Aires. The book was then a fourth year in production.

I have mentioned that in the months before I met him Borges had chosen – had been forced to choose – isolation as his daily lot. Worse than his isolation was his stark loneliness. No one came to visit, he told me, and after a while he asked if I could come to work with him on Sundays. His empty Sundays seemed to him to yawn on for ever. I was puzzled by this – the crowds at his public lectures, the emptiness at home – but I did not press him for an explanation. In the flat there was great tension between him and Elsa, which I feigned not to notice. I could see that he was immediately cheered by our work together, and he told me it gave him justification for his existence.

I said he told me that no one came to see him, but I remember that for a couple of days during my early visits a black boy, who may have been a Harvard student with an interest in writing, would be sitting in the kitchen with Borges. The young man said nothing, and Borges said nothing to him. I felt that Borges wanted to get rid of him by maintaining silence and not responding. As Borges snubbed him, the lad stopped coming. Borges never mentioned the incident nor did I.

Fani, the Borges’s Argentine maidservant, reported that one day in Buenos Aires Borges received a visit from two Brazilian women. ‘They stayed the whole afternoon,’ Fani said. ‘When they left the señor came to the kitchen and asked me what they were like physically. I told him they were blacks. “What do you mean blacks? Why didn’t you tell me? ¡Qué horror, I would have thrown them out!”’

I don’t know what it was about black people, but he did have an aversion to them. He sometimes wrinkled his nose and spoke of their catinga, an Argentine word for the smell of their sweat.

For her part, Elsa too seemed pleased to welcome me into the fold. I lifted her out of her gloom. My presence gave her more time for herself, needed space from Borges, and some new company she could trust.

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.