Sadece Litres'te okuyun

Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

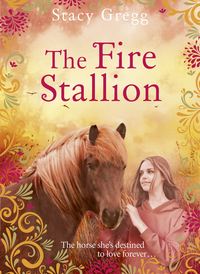

Kitabı oku: «The Fire Stallion»

Stacy Gregg

Bir şeyler ters gitti, lütfen daha sonra tekrar deneyin

₺1.019,86

Türler ve etiketler

Yaş sınırı:

0+Litres'teki yayın tarihi:

30 haziran 2019Hacim:

243 s. 72 illüstrasyonISBN:

9780008261436Telif hakkı:

HarperCollins