Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

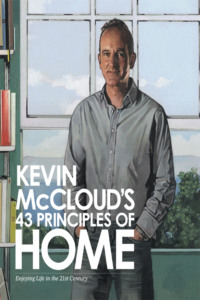

Kitabı oku: «Kevin McCloud’s 43 Principles of Home: Enjoying Life in the 21st Century», sayfa 2

Q: Which is the most eco-friendly car in this list?

A Toyota Prius

A 1937 Alfa Romeo tourer

A Ferrari

A 37-year-old Bond 875 (my first car)

The Innocent Smoothie van

An Aston Martin DB9

A Range Rover

You might plump for the Prius as the angel of the pack and the Range Rover as the devil.

Let me ask you another question: if you had the money, would you commission a small firm of English cabinet-makers to make you a bespoke, crafted piece of furniture? Or buy a cheap copy from the Far East? Well, the more ethical solution has to be the former: it’s a local transaction, it involves much less shipping, it creates relationships between the makers and the owner. The automotive equivalent is buying an Aston Martin over a Toyota Prius.

Surely this is rubbish. The Prius emits 145 grams of carbon per kilometre while the Aston emits nearly 500. But even these figures are meaningless. Who is the biggest environmental sinner? The man who drives his Prius 20 miles to and from work each day? Or the man who travels 50 miles on the train? Or the man who owns an Aston Martin and walks across his yard to his office and drives his car at weekends only? It’s probably the Prius driver.

This is just an exercise to point out that whatever you think of executive SUVs, hybrid cars and GT sports cars, calculating the environmental impact of these vehicles is very complex and ultimately dependent much more on how we use our vehicles than how big their engines are or where they were built.

So here’s another little test.

Q: Which do you think is the most environmentally friendly house?

1. A 500-year-old farmhouse, built from local materials—any stones that were just turned up out of the field—and oak trees from the farm in which it sits, with stone floors laid on the earth and thick walls with a high thermal mass. Albeit the place is listed and hasn’t got double glazing.

2. A house built by Ben Law in the forest in Sussex, entirely from the forest in Sussex. Ben cut 10,000 shingles from his own coppiced chestnut trees. The frame is coppiced chestnut and the oak cladding, straw-bale insulation and ash window frames are all from his woods and cut and assembled by him. This place does have double glazing, and it’s off grid, has its own water supply and is heated by Ben’s own wood thinnings from his sustainable forestry business, making charcoal and hurdles.

3. A three-bedroom family home in Scotland. It has super-insulated walls, it’s airtight, it has a state-of-the-art Panelvent timber panel construction sitting on a concrete plinth for high thermal mass, it’s triple-glazed and it comes with a heat recovery system.

So which is greenier than green? Well, it has to be Ben’s, of course. Maybe followed by the Scottish timber box. With the farmhouse a poor third, maybe. Which, it turns out, has no oil-fired range, has 10 inches of loft insulation and is heated with a biomass boiler.

Again, it’s down to use. You can construct a super-insulated, resource-meagre dwelling, turn the heating up and then open all the windows. Or live in a freezing mansion with no heating and one bath a week. There is no such thing as an eco-home, just as there’s no such thing as an eco-car. It’s our use of these things that determines not how environmentally friendly they are but how environmentally friendly we are.

1 Peter Marcuse, Environment and Urbanization, vol. 10, no. 2, October 1998

2 Our Common Future, OUP, 1987

3 Stern Review on the Economics of Climate Change, HM Treasury, 2006

4 www.bioregional.com/our-vision/one-planet-living/

5 Paul King and Pooran Desai, The Little Book of One Planet Living, Alastair Sawday, 2006

Part 1 Energy

Chapter 01 Setting Fire to Things

There are those days when the sun just hammers down through a blue sky and you think to yourself what a fine day for a barbecue. At least you do if you’re an unreformed male who jumps at every opportunity to reach back into the cave and set fire to something. Men who have been known never to stray within thrown pan range of a kitchen cast their husbandly reputations to the wind in order to incinerate as much protein as they can find in the fridge.

B-B-Q-ing is a man thing: an atavistic chest-banging, wandering-around-the-woods-sniffing-each-other’s-bottoms thing that connects male human beings to their pasts and the pasts of all their friends and their friends’ bottoms. Barbecues have done more for the social integrity of our modern world than all the Beaver Societies, Round Tables and Working Men’s Clubs put together. Alcohol may play a part. But the tradition of overcooking food on an uncontrollable open fire is a venerable social glue.

Stephen Pyne, professor at Arizona State University and fire expert, even goes so far as to describe fire as something dependent on life itself, not the other way around, which is what you would expect. You have to discount burning comets, volcanoes and lightning from his argument, but he is right when he points out that for a proper conflagration you need organic materials to burn: wood, trees, grass and dry leaves and their fossilized products such as coal, tar and oil. These materials in turn need sunlight and water to grow. In effect fire and water and the oxygen-rich air that plants produce are all part of the same cycle. ‘Fire is a creation of life: terrestrial life provides the fuel, and life everywhere furnishes the oxygen required for combustion.’ 1

Man’s relationship with fire has historically been a far more controlling one than you might imagine. Around 5,300 years ago a traveller died in the Tyrolean Alps at an altitude of 10,400 feet and was preserved in the ice until 1991, when he was dug up, named Ötzi and given his own museum. Ötzi died having been chased and struck with an arrow, expiring while clutching a last remaining comfort, a small box made of birch bark. In it, wrapped in fresh maple leaves, were lumps of charred wood. Either Ötzi was just setting up an alpine barbecue for some friends who decided to kill him and run off with the raw meat, or he was carrying smouldering charcoals, a source of warmth and a readily portable form of fire. 2

‘With or without people, the Earth will burn, though its human firebrands preferentially consume biomass by means of combustion and burn it in particular ways. They use their firepower to reshape the planet, to render it more suitable to their needs. In effect, humans … cook the earth.’

But in using such a powerful tool to reshape the planet, humans have developed a psychological relationship with fire as well.

‘Nearly all fire origin myths identify the acquisition of fire as the means of passage from life among the beasts into special status as a human being. In ecological terms that mythology contains more than a kernel of truth. Anthropogenic fire is as much a cultural artefact as are chopping stones and skyscrapers. And landscapes forged in those fires are as much a creation of human societies as are marble sculptures and parking lots.’ 3

I like to think that fire has elevated me from the level of ‘beast’ to my special status as a human being. I have a good relationship with fire. At home I have three woodburners to heat my house, which consume timber that I grow on my farm. Three years ago I installed a 120-kilowatt Austrian woodchip burner to heat the whole farm, including the outbuildings that I rent out to businesses and offices. It runs on chipped waste timber from things like broken pallets and it burns the stuff with the same gusto and noise as a Eurofighter Typhoon on afterburn. I’ve got my own miniature inferno to play with.

If the 18th Century inventor Benjamin Franklin were around today he would delight in the high-tech screen that spews out performance statistics in English and German (it only talks in German when it goes wrong but he would have spoken back to it in German or French or Latin). He would marvel at the self-feeding augur screw and sweep arm that suck the woodchips from the 90-cubic-metre storage bin next door. Benjamin Franklin was a man of fire, among many other things. And those other things were prodigious.

One of my woodburners is a Franklin, designed to sit in a large inglenook, and I’m fond of it. It has doors that can be left open to enjoy the flames or shut to keep a fire in overnight. Separate sliding plates govern how much air can be let in for combustion and how large the exhaust port is. Together with the doors, these plates minutely control what happens inside the stove and have been the stock-in-trade features of any and every cast-iron woodburner ever made. Except Benjamin Franklin figured it out first. His lifetime’s letters are peppered with correspondence with gentlemen from all over the globe seeking to improve the efficiency of their homes’ heating: how they might stop their rooms from being choked with smoke when the wind changes direction; how they might get better value out of their fuel and live more comfortably and safely. And for Franklin, it seems that dealing with this steady barrage of requests was if anything a pleasure.

Perhaps this was because fire was in his blood: his grandfather had been a blacksmith in England. Perhaps, though, just as Ötzi knew fire to be essential to survival and a tool to manipulate nature, Franklin knew that controlling energy was to become the most significant source of economic growth for any emerging country. Here was a man who depended on heat for his scientific experiments, who was discovering the extraordinary potential power of electricity in nature, who saw his friends set up furnaces and foundries, and who saw the incipient application of science and the enlightenment in industry and the growth of national prosperity. He didn’t just enjoy what energy had to offer: he could see its value. And its extraordinary destructive force, too. Which is why he set up the Union Fire Company in 1736.

If Franklin were around now, I know one thing that he would remark on and that is how setting fire to things in the 21st century has moved from the open fire to the closed one. We set fire to things in metal boxes now. As Pyne says, humanity has metamorphosed ‘from the keeper of the flame to the custodian of the combustion chamber’. 4

Franklin might be amused to see how his invention, a metal chamber in which wood could be burnt more efficiently and controllably, would come to be seen as the first internal combustion machine. Its descendants power our cars and planes. But I think he would equally be aghast at how we take fuel for granted now. In Franklin’s time you either had to chop down a tree (which would warm you once), stack the wood (warming you twice) and then bring it indoors to burn. Or you had to pay someone to do it for you, leaving a cold, empty feeling in the wallet. Either way you had direct contact with the fuel, its source and the human energy required to get it as far as the hearth. And not surprisingly you were interested in as many means of making that process more efficient, and in getting as much heat out of the fuel as possible. Nowadays fuel comes through rubber hoses from underground tanks or out of an electrical socket. Franklin would have loved to see that, the ‘commodiousness’ or ease with which fuels can get to our homes. But he would have scratched his head at the fuel inefficiency of a 4-litre Porsche Cayenne. He might even have wondered why he’d bothered.

But there is still something to be said for the inefficiency and beauty of an open fire—which is why Benjamin designed my stove with big folding front doors that can be opened. If you enjoy looking at the flames of an open hearth licking up the chimney, then you should make a visit to a blacksmith’s forge. You’ll see and hear material combust as though in the Devil’s own crucible. If I get bored burning wood, I can wander over to the forge that Richard Jones runs in the yard next door. It’s another open fire, and one that in design has not changed much for several thousand years. Richard burns coke at temperatures hot enough to soften steel and melt your iPod. That’s what happens when you start burning things in the open air. He also occasionally cooks food on coals chucked into a 50-gallon oil drum vertically sawn in half to form a large half-round tray with a steel grille laid on top. Good basic cooking. And thanks to the racks of steel stock he buys in, I’ve been able to nick the odd length of half-inch bar to pursue my own DIY barbecue projects.

Principle 01

Demand that your home consumes the minimum of energy yet keeps you warm and comfortable. Demand a healthy environment with fresh, clean air. Demand that your building does not just save energy but produces it. Demand that your home has a minimal environmental footprint and uses our precious resources wisely and sparingly.

He lived for almost the entire 18th century—from 1704 to 1790—and has been described as the ‘first American’; his written contributions to the American Declaration of Independence assured him of that. But he was also a polymath, printer, inventor, scientist, statesman, soldier, diplomat, philosopher of the Enlightenment and social activist. He lived in England, Europe and America. He founded the first volunteer fire brigade and the first public lending library in America. He invented bifocals, the speedometer, swimming aids and musical instruments. His work on electricity made him world famous. And he spent a lifetime perfecting a particular invention, the Franklin stove.

Here’s a list of my homemade barbecues to date. Not all of which have been successful:

For this version I took a leaf out of my camping friend Phil’s book and dug a fire pit. Sounds impressive, but it is in fact only a shallow hole in the ground around 1 metre in diameter and 20 centimetres or so deep. What is attractive about this version is that it retains the heat in the earth around the fire, is draught proof, being under ground level, is a lot cheaper than a barbie from the DIY shed and puts you in touch with your caveman self. Ugg. It also works both as a grill (lay some metal mesh over the hole and you have your griddle) and as a stove. This is where the three lengths of half-inch bar come in useful. Stack them to form a tripod and tie together with soft wire at the top. The bottom ends should be shoved into the ground and then you can hang a chain and pot from the top point. Fill pot with food and some water, light fire and watch food cook for several days before serving woodland stew. Do not allow small children to fall into fire pit.

This was probably the least efficient and most dangerous version and wasn’t actually a barbecue but just a griddle placed on top of an open fire lit outside the kitchen on some open hard-standing on the farm. ‘Hard-standing’ is an agricultural term for concrete. When you light a fire on concrete, it cracks and expands massively. In fact it explodes. Which by itself represents a danger to life and limb. But of course it wasn’t just shards of concrete that flew through the air in every direction for 5 metres: it was burning wood, scalding embers, griddle and superheated sausages. I had to do a lot of explaining to the parents of my niece’s friend, who wandered home covered in what looked like enthusiastic love bites. Not good.

The problem with both Mks I and II is that you have to spend some time on your knees. So when it came to rebuilding part of the garden at home with raised beds, set in between with benches made from sleepers, I thought how civilized it might be to incorporate a barbie. Not one of those nasty pressed-steel machines with plastic wheels and a gas bottle hidden inside. That isn’t a barbecue, that’s the culinary equivalent of a leaf blower: another ridiculous outdoor machine that should never have been invented and which, when you use it, makes you look and feel less like Caveman and more like Modern Man who Can’t Cope. Ötzi’s notion of leaf blowing was entirely to do with keeping his charcoal fizzing.

I wanted a barbecue in that robust home-made 1970s way. So where better to turn to than the Reader’s Digest Complete Do It Yourself Manual of 1968. Terence Conran’s Garden DIY (1995) was helpful too. But the spirit of the brick-built barbecue is rooted in the era of Starsky and Hutch and Shampoo. I don’t have a pool with a pool boy, so a barbecue’s the next best thing. Mine was of quite modest proportions, brick built, rendered, set into the sleeper wall of a raised bed and surrounded with lush planting. It had a storage space underneath, a hearth base and a low wall surround topped with some metal mesh. Altogether fit for purpose.

I’ve used it now twice in five years. The first time to cook some fish that my son caught. I’d forgotten about the hard-standing thing until all the cement render around the barbie started to crack and splinter with the heat—although the fish was untainted. Delicious, in fact. So next time no render. Remember that. The second time was on a blistering summer’s day when I set fire to not only the charcoal but also the garden. The lush planting surrounding the barbecue comprised big miscanthus and zebra grasses, their considerable height added to by the height of the raised bed, so they presented a wall of green 10 feet high. To watch the odd dry frond catch the flame and crackle as it vanished was amusing for the first few minutes. To watch the whole bed of plants—about 2 metres by 6 –go up in a sheet of roaring flame was spectacular and a bit hairy, and not planned. I didn’t feel like having lunch that day, sitting in a charred wasteland.

And I have never used the thing since because of one logistical error: it’s about a two-minute walk from the kitchen—too far to bother really. Now I’ve gone and bought a simple forged steel barbecue, Mark IV, from the local hardware store. I suspect it’s made in China, because the stainless-steel components of it (griddle, tool rack, etc.) are rusting. But the thing is light and very serviceable, and I can keep it near the kitchen. It gets used more than anything I’ve ever tried to build myself and Benjamin Franklin would frown but be almost satisfied.

Given the special relationship between people and flames, and especially given the capricious and destructive nature of fire, it is hardly surprising that we have come to invest combustion with god-like powers. In 1841 the fuel specialist John Holland wrote:

Besides its importance as an auxiliary in the Hebrew sacrifiture, fire became an object of actual worship with several Gentile nations in the East. The Chaldeans accounted it as a divinity; and in the province of Babylon there was a city of Ur, or of fire, consecrated to this usage. The Persians also adored God under the similitude of fire, because it is fire that gives motion to everything in Nature: they had temples called Pyroea, or fire temples, set apart for the preservation of the sacred element… In Old Rome, fire was worshipped in honour of the Goddess Vesta, and virgins called vestals were appointed to keep it up. 5

Holland himself was an enthusiast of fire. He saw its anthropological and social value and recognized four chief uses for it:

–In connexion with Religion

–For culinary purposes

–For promoting personal comfort by means of warmth

–For the various operations of Metallurgy and the Arts.

What he failed to identify was a fifth use already expanding widely in popularity: locomotion. A century and a half later, transport of materials by lorry, car mobility powered by engines and holidays powered by turbofan jets are the increasingly hungry consumers of fossil fuels.

Not that we perceive or understand fire any more. Its visible and symbolic roles in the hearth and incense burner have been replaced by more covert and mundane roles. And more diverse too. Whereas in 1841 we might have kept a couple of coal or wood fires going at home in the kitchen range and drawing-room fireplace, today we might have a condensing gas boiler for heat, cook on electricity from a nuclear or diesel or coal-fired power station and drive a car that runs on gasoline—or maybe bioethanol if we’re progressive and American. We may not use colza oil lamps or burn whale oil (we still light the occasional candle made from processed animal fat, stearine) but generally our fuel use is far more sophisticated and freely available. About the only thing we burn as primitively as we did then is tobacco. Oh, and charcoal in the barbecue—but more of that later when we really do get cooking. Generally, we use more fuels to live faster, more luxurious lives, but we don’t know anything about those fuels or where they come from. Nor, it seems, do we care. And consequently we’re finding it rather hard to accept what all that burning might be doing to our atmosphere.

Holland held a rather quaint view, quite to be expected for his pre-oil time, that, without coal, the fuel of the age, a society’s fabric would crumble: ‘Our cities and great towns must then become ruinous heaps for want of fuel, and our mines and manufactories must fail from the same cause, and consequently our commerce must likewise fail.’ 6 It’s curious to compare his view with that of modern environmentalists who foresee the same fate befalling us but through an overuse of the same kind of fuel that Holland celebrated. Yet Holland was right, because it is cheap affordable energy, concentrated in an insanely efficient way in our fossil fuels, that has helped to build the modern world.

You might be forgiven for thinking that, in advocating burning things and in attempting to persuade you that burning things is not only good but also part of the earth’s natural systems, I’m encouraging us all to go out and burn more. I’m not. I’m just making the point that, despite our relationship to all kinds of fuel being an honourable one, we have forgotten what fuel is and where it comes from. Just as children nowadays know that fish are rectangular and orange and come in boxes, so adults believe that petrol is an alien, synthesized chemical and comes out of a hose from a tank in the ground to be briefly glimpsed and smelt on its way into the bowels of your 4x4. We don’t understand petrol; we don’t even see it being burnt. It’s a fossil fuel, but when we use those words what we really should be saying is that petrol comes from trees—from the trees and plants that rotted hundreds of millions of years ago to make our coal and gas and oil reserves. So it’s interesting that Pyne uses that word biomass to describe pretty well all the fuels we have available to us, be they coal, petrol, benzene, charcoal or straw. They are all, he reminds us, the products of photosynthesis. Plant growth is what keeps us warm, fed, moving and clothed, and we shouldn’t forget it.

*

Time to experiment with some fuels, then, and see how they burn. By which I mean see them burning.

A physicist may tell you that fire is just extremely rapid oxidation, whereby perfectly normal substances such as petrol, wood and old copies of Nun Wrestling magazine will alchemically transform to cinders before your eyes. When deprived of oxygen such combustible materials won’t burn; so you should know that it is impossible to set fire to risqué magazines in space, for example. On Earth, I know from experience how difficult it is to set fire to a straw bale. This was a scientific test and a highly necessary one that I conducted in 2000 because I was about to build a studio for myself out of straw bales because they are cheap, available and very good building insulators, both thermally and acoustically. I just wanted to make sure they were also not prone to bursting into flames if a casual passer-by tried to set light to my workplace. Of course when built my studio was going to be rendered on the outside and plastered on the inside, with not a single straw to stick out like a tempting fuse. But for my own peace of mind I had to know just how vulnerable the building was.

So on a dry and windless spring morning I carefully cleared a large area of our concrete farmyard and laid several fire extinguishers around (chiefly for effect). In the centre I heaved one very dense bale of straw up on to a pair of trestles. To the side, two small steel fuel containers, one half full of petrol, the other of diesel; a pair of long gauntlets, safety glasses and a woollen balaclava that I knew I could pull down over my eyebrows if it all went wrong. The balaclava had to be wool because I remembered from my days designing theatre sets that silk and wool, being animal based, are self-extinguishing –at least up to a temperature where everything else has long gone up in flames (useful that animals, at least at their first point of resistance, are self-extinguishing. Animal fats, of course, are not and they’ve been supplying us with candles, tapers, rush lights and lamp oil for millennia). A polyester balaclava would have been no good because it would have melted into my eyebrows. In my pocket I had some matches.

Principle 02

Sustainability is not a bolt-on, nor a government department, but a culture: a way of doing things.

Principle 03

A sustainable way of life means not a diminution of choices but a change of choices and an increase. It can be measured not in terms of standard of living but in quality of life.

The first test was a resounding success, in that the moment I put the lit match to the loose straw around the bale it crackled, burst into flame and then quickly spread more jumping flames around the surface of the bale before going out completely. Only the loose straw had caught and my bale was left more or less intact with a few charred strands on it. I’d just given it a haircut. So I waited half an hour, to be safe, and then carefully poured a little petrol over it, as if dousing it gently in gravy. When lit, this caught fire spectacularly. In fact it didn’t so much catch fire as form a giant fireball that ascended, wreathed in swirling black smoke. The petrol had started to evaporate even before I’d struck the match. I kept looking at the flaming bale and then the fireball and then the bale, thinking, Flames, fireball, flames, explosion? But the bale just went out again. The petrol was gone. It had been heated, evaporated and ignited in a few seconds, leaving a blackened but to all intents and purposes completely unburnt straw bale in the wake of its rocket-like ascent. I waited another half-hour. Then I remembered to put the balaclava on. Then I poured a few gravy boats of diesel over my indestructible bale and waited for the fuel to leach slowly through the straw and soak it good and proper. This time it had to go up in flames, surely?

The important thing I’ve learnt since about diesel is that it’s very hard to ignite. Diesel engines work by compressing the fuel until it explodes, not by introducing a spark as a petrol engine does. A straw bale soaked in diesel fuel can stink of the stuff but it might as well be soaked in water for all the enthusiasm it can muster when approached with a lit match. The fact that my bale didn’t present me with anything other than pre-charred straw didn’t help. It meant I was trying to set fire to something I’d already set fire to. I had to get a blowtorch.

This was a good idea, because getting what fire officers call a ‘satisfactory spread of flame’ was very enjoyable with the torch, like grilling the sugar on a giant crème brûlée. The bale crackled and the fire started to spread. This was exciting and not a little worrying, not least because I was generating an enormous cloud of black smoke and hadn’t told any of the neighbours. They must have thought I was burning tyres. But this felt good: the bale was really on fire. And so were the trestles underneath. They were going like jet-engine afterburners. Time to pull back.

What happened next was a surprise. One of the trestles, admittedly not very sturdy, collapsed. There was a great rush of sparks and vertical flame as wood fell on wood, the trestles fell on each other in a huge conflagration of fuel-soaked timber and the bale rolled free—only to go out. As the wood roared its way up the super-oxygenated space highway to oblivion, my straw bale lay intact, smouldering and defiant on the concrete. The air just couldn’t get into it. It was too dense, too thick, too stupid to catch fire.

There’s a thought. Some things are just too stupid to burn. Others, too clever at it. Best to surround yourself with stupid materials, then.

NB: when it’s loose, straw burns freely—too freely as a fuel, but it makes useful kindling for a barbecue. You don’t want to use petrol or diesel, of course, because they’ll taint the food and remove your eyebrows. Best to start with some straw, dry newspaper, dry leaves or brown cardboard, all of which burn well, and then add your charcoal, the ideal fuel for cooking. And come to that the ideal fuel for burning in your fire too.

*

Charcoal has a certain magic to it, an alchemical quality. Scientists call charcoal the solid carbon residue following pyrolysis (carbonization or destructive distillation) of carbonaceous raw materials. Which is accurate but incomprehensible. I call charcoal the miracle transformation from useless wood into an extraordinary useful fuel.

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.