Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

Kitabı oku: «World War Two: History in an Hour»

WORLD WAR TWO

History in an Hour

Rupert Colley

About History in an Hour

History in an Hour is a series of ebooks to help the reader learn the basic facts of a given subject area. Everything you need to know is presented in a straightforward narrative and in chronological order. No embedded links to divert your attention, nor a daunting book of 600 pages with a 35-page introduction. Just straight in, to the point, sixty minutes, done. Then, having absorbed the basics, you may feel inspired to explore further.

Give yourself sixty minutes and see what you can learn ...

To find out more visit http://historyinanhour.com or follow us on twitter: http://twitter.com/historyinanhour

Contents

Cover

Title Page

About History in an Hour

Introduction

Germany Invades Poland: ‘This is how I deal with any European city’

The Finnish–Soviet War: The ‘Winter War’

The Norwegian Campaign: ‘Missed the bus’

The Fall of France: ‘France has lost a battle but France has not lost the war’

The Battle of Britain and the Blitz: ‘It can only end in annihilation for one of us’

The Mediterranean: ‘One moment on a battlefield is worth a thousand years of peace’

North Africa: ‘A great general’

Germany’s Invasion of the Soviet Union: ‘The whole rotten structure will come crashing down’

War in the Far East: ‘Your boys are not going to be sent into any foreign wars’

The Battles of Stalingrad and Kursk: The new field marshal

The Holocaust: ‘The man with an iron heart’

The Battle of the Atlantic: ‘The U-boat peril’

The Big Three

Italy Falls: ‘You are the most hated man in Italy’

The Bomber Offensive: ‘My name is Meyer’

The Normandy Invasion: D-Day

France Free: ‘Liberated by her own people’

Approach from the East: ‘For the good have fallen’

The End of the War in Europe: The Death of a Corporal

The End of the War in Japan: ‘Complete and utter destruction’

Appendix 1: Key Players

Appendix 2: Timeline of World War Two

Copyright

Got Another Hour?

About the Publisher

Introduction

Lasting six years and a day (until the formal surrender of Japan), the Second World War saw the civilian, both young and old, fighting on the front line. Civilian deaths accounted for 5 per cent of those killed during the First World War; but during the Second, of the 50 million-plus killed, they made up over 66 per cent. During the 2,194 days of the conflict, a thousand people died for each and every hour it lasted. With eighty-one of the world’s nations involved, compared to twenty-eight during the First World War, this was a world war in the truest sense.

Germany Invades Poland: ‘This is how I deal with any European city’

The Nazi-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact, signed on 23 August 1939, allowed Hitler to pursue his ambitions in the east without fear of Russian interference; ambitions that included the destruction of Poland and the subjugation of its people. The attack on Poland began at 4.45 on the morning of Friday, 1 September 1939.

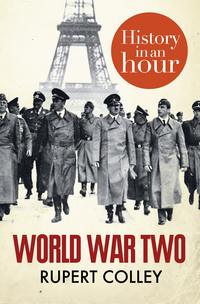

Hitler inspects German troops invading Poland, September 1939

Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-S55480 / CC-BY-SA

The Germans, not intending to be bogged down again in a war of trenches and stalemate, swept aside all resistance in a lightning war of blitzkrieg, using technological military advances, co-ordinated attacks and abrasive speed. Following up the rapid advances, German forces engaged in brutality, executions and merciless aggression against the civilian population.

Neville Chamberlain, who had been Britain’s Conservative prime minister since 1937, and who five months earlier had guaranteed the Poles assistance if attacked, dutifully declared war on Germany on 3 September followed, six hours later, by the French. The British contribution to the Polish cause was not with arms, nor soldiers, nor aid, but with leaflets – by the million, dropped by plane over Germany, urging the population to stand up against Hitler and the war.

On 17 September, as the German war machine advanced its way towards Warsaw, the Soviet Union as secretly agreed in the Non-Aggression Pact, attacked from the east. Crushed between two totalitarian heavyweights, Poland crumbled, and on the twenty-seventh, Warsaw surrendered. Agreeing on the partition of Poland, the Germans and Russians then set about the total subjugation of the defeated population. Villages were razed, inhabitants massacred, the Polish identity eradicated; and in towns, such as Lodz, Jews were herded into ghettos before eventual transportation to the death camps. With his first objective achieved, Hitler visited Warsaw on 5 October, and casting a satisfied eye over the devastated capital, declared: ‘this is how I deal with any European city’.

The Finnish–Soviet War: The ‘Winter War’

Stalin, knowing that his country’s pact with Germany would not last indefinitely, sought a buffer zone against any future German attack. By June 1940, he had bullied Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania into co-operation, swiftly followed by full annexation. Finland, however, resisted, preferring to fight than submit to Soviet demands. The 105-day ‘Winter War’ started with Russia’s attack on Finland on 30 November 1939. Russia, expecting an easy victory as the Germans had had over the Poles, was soon disabused, underestimating Finnish bravery, tenacity and expertize at guerrilla warfare.

Finnish soldiers during the Soviet–Finnish War, February 1940

Coupled with the Soviet Union’s lack of military proficiency, following Stalin’s military purge of the 1930s, and poor equipment that froze in the plummeting temperatures, the Soviets learnt a hard but useful lesson, eventually subduing the Finns in March 1940 by sheer weight of numbers.

The Norwegian Campaign: ‘Missed the bus’

The supply of iron ore from Sweden to Germany via the northern Norwegian port of Narvik was essential to the German war machine. Both the Germans and British decided to take Narvik, the former to protect its supply route, the latter to disrupt it. When, on 8 April 1940, British ships started laying mines off the Norwegian coast, Chamberlain crowed that Hitler had ‘missed the bus’.

But the Germans advanced swiftly into Scandinavia, forcing Denmark into a rapid surrender and compelling neutral Norway to take up arms as, one by one, her ports fell to the Germans. The British response, although fast, was dogged with inefficiency and disruption, with troops landing in snowy Norway without skis and provided only with tourist maps. When, on 10 May, Germany attacked Holland and Belgium, British forces in Norway were evacuated to the Low Countries, leaving Norway to fall under German control and to be ruled by the Norwegian Nazi, Vidkun Quisling.

Winston Churchill, as First Lord of the Admiralty, took responsibility for the Norwegian debacle, but it was Chamberlain, as prime minister, who fell. Unable to form a coalition government, he was forced to resign amidst shouts in the House of Commons of ‘Go, go, go!’. He was replaced, ironically, by Churchill. The date, 10 May, was the day that Hitler unleashed blitzkrieg south of the Channel. Six months later, Chamberlain was dead.

The Fall of France: ‘France has lost a battle but France has not lost the war’

The period from the beginning of the war to 10 May 1940 was known in Britain as the ‘phoney war’, when the conflict still seemed far away. Children were evacuated to the countryside, rationing was introduced, as were evening blackouts and the carrying of gas masks.

Belgium, overwhelmed by the German advance, appealed to the Allies for assistance. The British and French responded by moving into Belgium to counter the German attack. Along the Franco-German border the French fielded a weaker force, putting faith in the Maginot Line, a defensive 280-mile-long fortification, built in the early 1930s as protection against the Germans. The Germans rendered it obsolete within a morning in May 1940 by merely skirting around the north of it, through the Ardennes forest, which, because of its rugged terrain, the French considered impassable. Reaching the town of Sedan on the French side of the Ardennes on 14 May and brushing aside French resistance, the Germans pushed, not towards Paris as expected, but north, towards the English Channel, forcing the Allies further and further back. In 1916, the Germans had failed to take Verdun despite ten months of trench warfare; in May 1940, it took them one day.

In Holland, Rotterdam was heavily bombed and, on 15 May, the Dutch, fearing further losses, capitulated. On 28 May Belgium also surrendered. Allied forces, with their backs to the sea in the French coastal town of Dunkirk, were trapped. But the Germans, poised to annihilate the whole British Expeditionary Force, were inexplicably ordered by Hitler to halt outside the town. Between 26 May and 3 June, over 1,000 military and civilian vessels rescued and brought back to Britain 338,226 Allied soldiers. This was not achieved without scenes of panic, broken discipline and soldiers shot by their officers for losing self-control. Meanwhile, Hitler’s generals watched, puzzled and rueing an opportunity missed.

Allied troops awaiting evacuation from Dunkirk to England, May 1940

On 4 June in the House of Commons, Churchill was careful not to call the ‘miracle of Dunkirk’ a victory but merely a ‘deliverance’. He continued to deliver his famous ‘We shall fight on the beaches’ speech, concluding with the immortal words, ‘We shall never surrender’. However, the French saw it somewhat differently – with the Germans closing in on Paris, they considered the Dunkirk evacuation a huge betrayal.

On 10 June, Italy declared war on the Allies. Four days later, Hitler’s forces entered a largely deserted Paris, over 2 million Parisians having fled south. Soon the swastika was flying from the Arc de Triomphe.

On 16 June, the French general, Charles de Gaulle (pictured below), escaped France to begin his life of exile in London. He was later sentenced to death – in absentia by the Vichy government. From London, de Gaulle broadcast a declaration, asserting that: ‘France has lost a battle but France has not lost the war … The flame of French resistance must not and shall not die.’ His words became the battle cry of the Free French movement.

Charles de Gaulle, 1942

Also on 16 June, the French prime minister Paul Reynaud resigned, to be replaced by 84-year-old Marshal Philippe Pétain, hero of the 1916 Battle of Verdun. Pétain’s first acts were to seek an armistice with the Germans and order Reynaud’s arrest. On 22 June, fifty miles north-east of Paris, the French officially surrendered, the ceremony taking place in the same spot and in the same railway carriage where the Germans had surrendered in 1918. Straight afterwards, on Hitler’s orders, the railway carriage and the monuments commemorating the 1918 signing were destroyed. The following day Hitler visited Paris, his only visit to the capital, for a whistle-stop sightseeing tour of the city. On visiting Napoleon’s tomb, he said: ‘That was the greatest and finest moment of my life.’ Before departing, he ordered the demolition of two First World War monuments, including the memorial of Edith Cavell, the British nurse shot by the Germans in Brussels in October 1915.

Hitler visits Paris following France’s defeat in June 1940

Pétain and his puppet government ruled from the spa town of Vichy in central France. The Vichy government actively did the Nazis’ dirty work: conducting a vicious civil war against the French Resistance, implementing numerous anti-Jewish laws, and sending tens of thousands of Jews to the death camps.

In July 1940, Churchill established the Special Operations Executive (SOE) to help resistance groups in France and elsewhere in Europe in the work of sabotage and subversion. In October 1940, Pétain met Hitler, and although Pétain opposed Hitler’s demands that France should participate in the attack on Britain, photographs of the two men shaking hands were soon seen across the world – evidence of Vichy’s complicity with the Nazis.

In July 1940, Churchill issued an ultimatum to the admiral of the French fleet docked in Mers-el-Kebir, Algeria – to hand the ships over to the British or scuttle them to prevent them from being used by the Kriegsmarine, the German navy. When the admiral refused to comply, Churchill ordered the Royal Navy to open fire, killing 1,297 French sailors. The incident served to sever relations between Vichy and Britain.

The Channel Islands were occupied by a German garrison from 30 June 1940 until the German surrender in May 1945. The only part of Great Britain to be occupied by the Germans throughout the war, there was almost one German for every two islanders. The islands were not of any strategic importance, but occupation of British territory was considered symbolically important to the Germans. Food supplies, delivered from France, were severely curtailed after the Normandy invasion of June 1944, and although the occasional Red Cross ship got through, by the time of liberation both the Germans and the islanders were on the point of starvation.

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.