Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

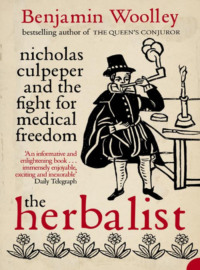

Kitabı oku: «The Herbalist: Nicholas Culpeper and the Fight for Medical Freedom»

THE HERBALIST

Nicholas Culpeper and the fight for medical freedom

BENJAMIN WOOLLEY

DEDICATION

In memory of Joy Woolley,

1921–2003

PREFACE

In the landscape of history, Nicholas Culpeper has not always been welcome. If monarchs, ministers, political notables and scientific luminaries are stately oaks or cultivated blooms, Culpeper is the Cleavers (or Goosegrass, or Barweed, or Hedgeheriff, or Hayruff, or Mutton Chops, or Robin-Run-in-the-Grass, to use any of its multitude of names), a common grass that is ‘so troublesome an Inhabitant in Gardens’, creeping into the herbaceous borders and snagging clothes. As a result, he has been weeded out of the historical record, and barely a trace of him is left. The only documentation relating to him that survives is a brief memoir, one letter, a couple of manuscript fragments, several tantalising mentions in official papers, and some pamphlets. His own voluminous writings brim with character, but are almost empty of biographical details. Official medical and botanical histories written while he lived and since have contributed nothing, and in some cases have taken a great deal away. For this reason, Nicholas’s presence in history, and in the account that follows, is necessarily fleeting.

However, hidden in the undergrowth is a startling story, entangled with so many others, with the struggles of the woodturner Nehemiah Wallington to survive the plague, with the mischievous prophesies of the astrologer William Lilly, with the Olympian struggles and self-belief of King Charles I, and most of all with the anatomical explorations and loyal ministrations of the King’s doctor William Harvey, the Isaac Newton of medical science and model of medical professionalism. Like the Cleavers and other discarded weeds championed in his Herbal, Nicholas certainly had ‘some Vices [but] also many Virtues’. His vices were well known, itemised by friends as well as his many enemies: smoking, drinking, ‘consumption of the purse’. But he was also audacious and adventurous. He championed the poor and sick at a time when they were more vulnerable than ever. He took on an establishment fighting for survival and ferociously intent on preserving its privileges.

The heirs of that same establishment are inevitably the custodians of much of the material upon which this book relies, in particular the Royal College of Physicians, which provided generous access to its archives. Acknowledgement must also go to the Society of Apothecaries, the British Library, the Bodleian Library at Oxford, the Cambridge University Library, the Records Offices of the counties of East and West Sussex, Kent, Surrey, and of London, primarily the Guildhall Library, the Corporation of London and the Metropolitan Archives. Individual thanks are due to Briony Thomas and the Revd Roger Dalling for local information on Nicholas’s childhood, to Dr Jonathan Wright for reading the manuscript and Dr Adrian Mathie for checking some of the medical information.

The dates given are new style unless otherwise stated. Spelling and punctuation have been modernised where appropriate. Notes at the back provide details on sources, clarifications and definitions of some of the medical and astrological terminology, and brief discussions of the historical evidence. One final note: the capitalised ‘City’ refers to the square mile that is the formally recognised city of London, a distinct political as well as urban entity with its own government and privileges, lying within the bounds of the ancient city walls. ‘London’ or the ‘city’ refers to the wider metropolitan area, embracing the city of Westminster to the west, Southwark on the south bank of the Thames, and the sprawling suburbs to the north and east.

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Preface

Tansy: Tanacetum vulgare

Borage: Borago officinalis

Angelica: Angelica archangelica

Balm: Melissa officinalis

Melancholy Thistle: Carduus heterophyllus

Self-Heal: Prunella vulgaris

Rosa Solis, or Sun-Dew: Drosera rotundifolia

Bryony, or Wild Vine: Bryonia dioica

Hemlock: Conium maculatum

Lesser Celandine (Pilewort): Ranunculus ficaria

Arrach Wild & Stinking: Atriplex hortensis, olida

Wormwood: Artemisia absinthium/pontica

Epilogue

Notes

Bibliography

Index

P.S. Ideas, Interviews & Features …

About the Author

About the Book

Read On

About the Author

Praise

By the Same Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

TANSY

Tanacetum vulgare

Dame Venus was minded to pleasure Women with Child by this Herb, for there grows not an Herb fitter for their uses than this is, it is just as though it were cut out for the purpose. The Herb bruised and applied to the Navel stays miscarriage, I know no Herb like it for that use. Boiled in ordinary Beer, and the Decoction drunk, doth the like, and if her Womb be not as she would have, this Decoction will make it as she would have it, or at least as she should have it.

Let those Women that desire Children love this Herb, ’tis their best Companion, their Husband excepted.

The Herb fried with Eggs (as is accustomed in the Spring time) which is called a Tansy, helpeth to digest, and carry downward those bad Humours that trouble the Stomach: The Seed is very profitably given to Children for the Worms, and the Juice in Drink is as effectual. Being boiled in Oil it is good for the sinews shrunk by Cramps, or pained with cold, if thereto applied.

Also it consumes the Phlegmatic Humours, the cold and moist constitution of Winter most usually infects the Body of Man with, and that was the first reason of eating Tansies in the Spring. At last the world being overrun with Popery, a Monster called Superstition perks up his head … and now forsooth Tansies must be eaten only on Palm and Easter Sundays, and their neighbour days; [the] Superstition of the time was found out, but the Virtue of the Herb hidden, and now ’tis almost, if not altogether, left off.*

Tansy has a tall, leafy stem, two or three feet high, with ferny foliage and flowers like golden buttons.1 Maud Grieve describes it as having ‘a very curious and not altogether disagreeable odour, somewhat like camphor’. The name probably comes from the Greek Athanaton, meaning immortal, either because it flowers for so long, or because of its use in ancient times to preserve corpses. It was said to have been given to Ganymede (‘the most beautiful of mortals’, carried off by Zeus to Olympus to serve as cupbearer and catamite) to make him immortal.

The herb was long associated not only with immortality but birth, hence the link with Easter, when, according to Grieve, ‘even archbishops and bishops played handball with men of their congregation, and a Tansy cake was the reward of the victors’. Richard Mabey, echoing Culpeper, writes that its original medicinal use at Easter time was to counteract the ‘phlegm and worms’ arising from the heavy consumption of seafood during Lent.

Though tansy has a strong, bitter taste, the cake was sweet. According to a traditional recipe, it was made by adding to seven beaten eggs a pint of cream, the juice of spinach and of a small quantity of tansy pounded in a mortar, a quarter of a pound of Naples biscuit (sponge fingers similar to macaroons, but made with ground pine nut kernels rather than almonds), sugar to taste, a glass of white wine, and nutmeg. The ingredients were combined, thickened in a saucepan over a gentle heat, poured into a lined cake tin, and baked.2

A dark, gnarled yew stood next to the lych-gate, poisoning with a drizzle of noxious needles anything that grew beneath it. Rose bushes still in flower were scattered across the graveyard, planted, according to local tradition, by the betrothed on the graves of their dead lovers. A mound of fresh earth marked the spot where, a few days earlier, Maurice Sackville, the late rector of Ockley, had been interred. This was the scene beheld on 15 September 1615 by the Revd Nicholas Culpeper, Sackville’s hastily-appointed successor. He had arrived just four days after Sackville’s funeral from his old post as vicar of nearby Alciston. He was in his mid-thirties and, for a country parson, uncommonly well educated, boasting a degree from the University of Cambridge.3

Ockley was a modest but busy parish on the border of the counties of Surrey and Sussex, straddling Stane Street, the Roman road that still acted as the main thoroughfare from Chichester on the south coast to London. The church itself was a quarter of a mile from the village, perched on a hill, next to the remains of a castle and Ockley Manor, owned by Nicholas’s cousin and patron Sir Edward Culpeper.4

Nicholas and Sir Edward were from branches of the same family that was joined three generations back, part of a voracious dynasty that grew like white bryony through the counties of Sussex, Kent, and Surrey. The origin of the Culpeper name is obscure. Some have speculated that it derived from the place where the first family members settled, perhaps Gollesberghe in Sandwich, Kent or Culspore in Hastings, Sussex. To most, however, it was more suggestive of politics than geography. ‘Cole’ was a prefix meaning a fraud, as in cole-prophet, a false prophet, or ‘Colle tregetour’, a magician or trickster mentioned by Geoffrey Chaucer in his poem The House of Fame.5 Colepeper, one of innumerable spellings, would therefore mean a false pepperer, someone trading illicitly as a grocer outside the Fraternity of Pepperers, the guild incorporated in 1345 which later became the Grocers’ Company. Or the ‘pepper’ could simply refer to the herb’s association with offensiveness. Jack Straw, a supposed leader of the fourteenth-century Peasants’ Revolt, was described by a contemporary writer as a ‘culpeper’, meaning mischief maker.6

Elements of the family had certainly lived up to this interpretation of the name. Wakehurst, the family’s main seat in Sussex, had come to the Culpepers after the daughters of its original owners were abducted by brothers Richard (1435–1516) and Nicholas (1437–1510). A grandchild of their elder brother John, Sir Thomas Culpeper, was beheaded in 1541 for treason, accused of being the lover of Catherine Howard, Henry VIII’s fifth wife, herself the daughter of Joyce Culpeper, Thomas’s sixth cousin, once removed.

By the early seventeenth century, the leading Culpepers were eager for respectability. Edward Culpeper, the current occupant of Wakehurst and the great-great-grandchild of Richard, had risen to become a Sergeant-at-Law (a high-ranking barrister). But in those days, lawyers, like physicians and merchants, were not considered gentlemen. Titles and land were the real currency of social rank, and Edward was ruthless in his pursuit of both. In 1603, he bought himself one of the new knighthoods that James I sold on his succession to the English throne in order to finance an opulent court. Through legal action as well as acquisition, Edward also enlarged his estate at Wakehurst into one of the most extensive in Sussex, and built an impressive mansion in the middle of it to show off his new-found status. Among the many lucrative plots for which he litigated was one of 120 acres at Balcombe, on the south-west border of his Wakehurst estate. This had been the principal possession of the Revd Nicholas Culpeper’s grandfather, leaving that branch of the family incurably reduced. Nicholas had inherited just £120 on his twenty-first birthday, enough to pay for his education at Cambridge University, where he received an MA in 1608. Thereafter he was dependent on the patronage of Sir Edward.

Now, as rector of Ockley, entitled to the living or ‘benefice’ generated by local church taxes, Nicholas could look forward to a comfortable, if undemanding, life. He had also become engaged to Mary, the twenty-year-old daughter of another rector, William Attersoll of Isfield, a village near Nicholas’s old parish of Alciston and within the same deanery or church administrative district.7 A month after Nicholas took up his position at Ockley, they were married at Isfield.

Nicholas’s first few weeks in the parish were busy with funerals. Coffin after coffin was carried past the old yew into the church yard, six before Christmas, a high number for a village with a population of a hundred or so. One of them contained Katherine Sackville, wife of the late rector, suggesting that both had succumbed to a disease passing through the village. Nicholas must have been concerned about the infection lingering in the rectory he and his new wife had so recently occupied.8

Within the year, Nicholas too was dead, around the time of the first anniversary of his marriage to Mary, who was about to give birth to their first child. There is no record of what killed Nicholas, but there was a ready supply of possible causes. At around this time, the practice began of hiring old women – ‘ancient Matrons’ – to roam parishes as ‘searchers of the dead’, recording the number and causes of death for regularly published ‘Bills of Mortality’. There was some controversy about this practice. According to John Graunt, who started analysing these figures in the 1660s, people questioned ‘why the Accompt of Casualties is made’, since death was a divine, not a demographic, matter; its time preordained; its cause the instrument by which God’s will was performed. No intervention, physical or otherwise, could prevent it. ‘This must not seem strange to you,’ advised William Attersoll two years before his son-in-law’s death, ‘for the whole life of a Christian should be nothing but a meditation of death … You must consider that nothing befalleth us by chance or fortune, all things are ruled and guided by the sovereign providence of almighty God.’9

Despite qualms about the searchers’ work, they were diligent in their efforts and came up with an elaborate catalogue of causes: apoplexy, bleach, cancer, execution, fainting in the bath, gout, grief, itch, lethargy, lunacy, murder, palsy (paralysis), poison, sciatica, and ‘suddenly’. But one class of cause prevailed over all these: infectious disease.

There was no concept of germs in the seventeenth century. Infection was a corruption of the air, a humidity or ‘miasma’ that exuded from the earth, a theory that lingers today in the belief in the benefits of ‘fresh’ or ‘country’ air. Some places were more prone to infection than others because they were near sources of this miasma, such as sewers and swamps. London, with its cramped streets, fetid streams, and cesspits, oozed contagion. But the countryside could be just as dangerous. Some settled rural populations – for example in remote parts of the West Country or on the chalk uplands of the Sussex Downs – had high levels of shared immunity to native bugs and lack of exposure to foreign ones. A village such as Hartland in Devon enjoyed infant mortality and life expectancy rates so low they would not be matched nationally until the 1920s. But other areas were as bad as any urban pesthole, notably large tracts of Sussex and Kent. ‘Marish’ and estuarine terrain, alluvial tracts, swampy low-lying basins, and sluggish rivers were suffused with ‘marsh fever’ or the ‘ague’ – malaria (from the Italian for ‘bad air’). The disease was familiar, and its diagnosis precise, categorized according to the frequency of the feverish attacks that announced its onset: daily (quotidian), every other day (tertian), and every third day (quartan).10 The convulsions produced by marsh fever, though distressing, were not usually fatal. However, they left sufferers more susceptible to enteric diseases – gut infections such as typhoid and dysentery. These were less clearly differentiated, but more deadly, frequently killing off one in ten of the population of a village in a single year.11

Just such a crisis seemed to overtake Ockley in 1615 and 1616. Autumn was the killing season for enteric infections, and nearly all of the twenty deaths in the parish during those years occurred between September and December. The summer of 1615 was particularly hot, and the stagnation of water supplies and sewers produced an epidemic of typhoid across the region.12 Perhaps it was this that carried away Nicholas Culpeper. If so, the sickness would have taken three weeks to pass through its elaborate pageant of pain: innocuous aches at first, possibly accompanied by nosebleeds and diarrhoea; a fortnight or more of high fever and skin rashes, interrupted by brief remissions. This was the first phase. The second was a week of tortuous stomach pains and delirium.

If he was in this state, very little could be done for him. Mary would have been expected to mix up some palliative medicines, based on recipes she had learned from her mother, or from local women with more experience. Typical remedies known to soothe the symptoms of fever were flowers of camomile beaten into a pulp and mixed with cloves and vervain, to be applied, as one herbal unhelpfully reported, according to ‘mother Bombies rule, to take just so many knots or sprigs, and no more, lest it fall out so that it do you no good’.13

A local ‘wizard’ or ‘cunning woman’ may have come to call. Bishop Latimer had noted in 1552 that ‘A great many of us when we be in trouble or sickness … run hither to witches, or sorcerers … seeking aid and comfort in their hands’.14 They were still a part of life in rural villages such as Ockham in the early 1600s, promising with remarkable assurance that they could heal a variety of ailments using a combination of magical rituals and semi-religious invocations or spells. Techniques included burning or burying animals alive, immersing sufferers in water flowing in a particular direction, dragging them through bushes, or touching them with a magical talisman or staff. Such methods were justified on the basis of no particular medical or magical theory, though many were inspired by the principle of sympathy – the idea that one thing (such as a disease) had an affinity with another that was similar or connected to it in some way. Thus, to cure a headache, a lock of hair might be taken from the victim and boiled in his or her urine.15

However, the Revd Nicholas Culpeper was very unlikely to have allowed such people near him. Their superstitious practices were closely associated with witchcraft, and a Christian minister would have considered them either fraudulent or diabolical. Mary’s attitude may have been different. She was still a comparative stranger in the village, having been in the parish for little more than a year, and was heavily pregnant, expecting to give birth any day. In such a state of isolation and vulnerability, as Nicholas lay unconscious on his sickbed, she may have yielded to the temptation of letting a charismatic healer through the rectory door.

She may also have called for a doctor, though his chances of success were little better. The nearest large town, Horsham, was ten miles away, and the county town of Guildford a further five, so it would have taken some time and cost for him to come. Had one been summoned, his most likely treatment during the feverish stage of the illness would have been bleeding and purgation – in other words letting blood from the arm and prescribing toxic herbal emetics and laxatives to provoke violent vomiting and the evacuation of the bowels. Mary would have had to administer these medicines both orally and anally according to a strict timetable, and they would have intensified her weak husband’s sufferings, forcing him to endure hours spending blood into a basin, retching over a bucket, and squatting on a chamber pot, until he was finally overcome.

The Revd Nicholas Culpeper was buried in his own graveyard on 5 October 1616. Less than a fortnight later, at 11 p.m. on 18 October 1616, in the dark of that dismal rectory, the venue for three deaths in thirteen months, his widow gave birth to their son. The boy, baptized six days later at Ockley church, was named Nicholas in honour of the father he would never know.

Sir Edward Culpeper’s patronage apparently expired along with his relation, and Mary was forced to leave the rectory almost immediately. Some time that winter, mother and infant set off along Stane Street, headed for the village of Isfield in Sussex, forty miles away.

The handsome parish church of Isfield is at the confluence of the Rivers Uck and Ouse in Sussex. It sits alone in the middle of a water meadow that floods during wet seasons, bringing water lapping up to the church gate. The small village it serves is nearly a mile away to the south-east, on higher ground. According to local lore (now considered doubtful), it moved there following the Black Death in the fourteenth century, to escape the unhealthy miasma thought to rise from the marshy valley bottom.16 This was the isolated domain of the man who was to be surrogate father to baby Nicholas, his grandfather William Attersoll.

The Revd William Attersoll was, like his recently deceased son-in-law, a Cambridge scholar, having taken his MA at Peterhouse in 1586. Now in his mid-forties, he had served as rector of Isfield since 1600 in a mood of resentment. The living was, by his estimation, ‘poor’. So was the ‘cottage’ that acted as his rectory. A minister of his education deserved better.

The deficiencies of his situation were exacerbated by an ungrateful and ignorant congregation. He was surrounded by ‘enemies to learning’, he claimed, whose judgement was no more valid ‘than the blind man of colours, or the deaf man of sounds’.17

The problem was his theology. Attersoll was a Puritan. The label is a difficult one, covering a multitude of opinions, not all consistent with one another. It was coined in the sixteenth century as a term of abuse (an Elizabethan equivalent of ‘fundamentalist’ or ‘extremist’) to refer to Protestant zealots.18 Those marginalized as Puritan by some were happily accepted as mainstream Protestants by others. They are characterized as hair-shirted ascetics who wanted to ban Christmas and close theatres, yet some of the most theatrical figures of the Elizabethan age – courtiers such as Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex, and Sir Walter Raleigh – were associated with the term.

Attersoll’s Puritanism was theologically absolute, and politically conservative. In 1606 he had published his first book, The Badges of Christianity. Or, A treatise of the sacraments fully declared out of the word of God. It was a critical examination of the role of various Christian rites based on a detailed examination of biblical principles. His idea was to purify religious ritual of a residue of Catholic tradition and restore it to the role ordained in the scriptures.

Like most rural communities, the villagers of Isfield were solidly anti-Catholic. However, it was nationalism, not religion, that fed their hatred of ‘papists’. Isfield was just a few miles from the south coast, which had been in a state of alert for over half a century, in constant expectation of a Catholic invasion that might well have happened but for the famous defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588. But on matters of religious practice, many wanted to keep the rituals that dated back to the Catholic era. Saints’ days and sacraments were woven into the pattern of their lives. They enjoyed church ales (parish fund-raising events during which potent home brews were sold) and tansy cake. They were reassured by visitations of the sick and ‘churching’, a service for accepting the mother of a newborn back into the congregation after her confinement. Such ceremonies provided them with ‘comfort and consolation’, as Attersoll grudgingly acknowledged. But he believed comfort and consolation could never come from the cosy familiarity of empty pageants. It must come from reading the scriptures, intense self-examination, and devout prayer. He disapproved, for example, of the Catholic ritual of applying ‘extreme unction’, healing holy oil, even though it was still common practice and widely believed to cure illness. No ‘material oil’ could heal them, he protested, only the ‘precious oil of the mercy of God’.19 Illness was even to be welcomed. ‘Sickness of the body is a physic of the soul,’ Attersoll said.20

Life for the villagers was tough enough without having to put up with this, and around 1610 they attempted to oust their austere rector. ‘The calling of a Minister, is a painful and laborious, a needful and troublesome calling,’ Attersoll lamented.21 Nevertheless, he was not prepared to go, and appealed for help to Sir Henry Fanshaw, another scholar and his mentor at Cambridge, who had since become an official in the Royal Court of Exchequer.

The manner of Fanshaw’s intervention is unknown, but it was successful, and Attersoll would continue as rector of the parish for decades to come. Perhaps as a snub to his parishioners, and probably encouraged by the appearance of King James’s Authorized Version of the Bible in 1611, he devoted more time than ever to biblical analysis, producing a number of hefty tomes over the next eight years: The Historie of Balak the King and Balaam the False Prophet (1610), an exposition on the Old Testament Book of Numbers that continued The Pathway to Canaan of 1609; A Commentarie vpon the Epistle of Saint Pavle to Philemon (1612); The Neuu Couenant, or, A treatise of the sacraments (1614); and a massive combined edition of his expositions on Numbers, the Commentarie vpon the Fourth Booke of Moses, in 1618. This was prolixity even by Puritan standards, in the case of the commentary on St Paul’s letter to Philemon, five hundred plus pages arising from just one in the Bible.

He was working on the Commentarie vpon the Fourth Booke of Moses when his daughter Mary appeared at his doorstep, carrying his infant grandchild Nicholas. Attersoll was unlikely to have welcomed the interruption, particularly as he may have been expecting the Culpepers to provide for his widowed daughter. Sir Edward Culpeper had innumerable properties scattered across his Sussex estate, including many close to Attersoll’s parish. Any one of these would have provided a comfortable home for Mary and her fatherless boy. Perhaps such offers had been made, and Mary had declined them in preference for her father. If that was so, the decision was one both he and she would come to regret.

Whatever the circumstances of Mary’s arrival in Isfield, Attersoll had no option but to accommodate mother and child in the cramped rooms of his ‘cottage’ and assume responsibility as Nicholas’s guardian. Being but a ‘poor labourer in the Lord’s vineyard’, the extra cost of having to provide once more for a daughter and now a baby must have a put a strain on Attersoll’s finances, and exacerbated the bile that had built up over his material circumstances.22

There is no mention of Attersoll’s wife at the time Nicholas was in Isfield, suggesting that he was a widower and had been living alone. He had at least one son, also called William, but he was at Cambridge at the time of Mary’s return to the household, preparing dutifully to follow his father into the Church. The university fees and maintenance costs would have added a further strain on the old man’s fixed income.23 This must have made the presence of a child in the midst of Attersoll’s cloistered, scholastic world all the more disruptive.

He certainly did not like children. ‘We see by common experience, that a little child coming into the world, is one of the miser-ablest and silliest creatures that can be devised, the very lively picture of the greatest infirmity that can be imagined, more weak in body, and less able to help himself, or shift for himself, then any of the beasts of the field.’ Looking at an infant, all he could see was the image of men ‘through sin & their revolt from God fallen down into the greatest misery, and lowest degree of all wretchedness’.24

Nevertheless, the care of children was a theme of great concern to him, because it related not only to the children of parents, but also to the children of God. Protestantism was a rebellion against the father-figure of the Pope (whose very title was derived from ‘papa’, the childish word for father). Some Protestants saw this as a liberation, allowing every Christian to find their own way to Christ, carrying the Bible and their sins with them, like Bunyan’s burdened hero in The Pilgrim’s Progress. But it worried Attersoll greatly. He saw ‘godly’ Protestants as being like the Israelites of the Old Testament, escaping the tyranny of the Pope just as the Jews had thrown off the tyranny of the Pharaoh. But the Jews had needed their Moses to guide them to the Promised Land.25 This is what drew Attersoll to the study of Numbers, the fourth book of the Bible, and the penultimate section of the ‘Pentateuch’, the five books said to have been dictated directly to Moses by God. Numbers told the story of the Israelites in the Sinai desert, and Attersoll noted how, as they gathered there, they ‘murmured’ against Moses. Led by Korah, Datham, and Abi’ram, they became idolatrous, conspiring and threatening to destroy, as Attersoll put it, the ‘order and discipline of the Church’ – his intentionally anachronistic term for the religious organization around the Tabernacle, the portable structure used by the Israelites as their place of worship during the Exodus.26 ‘Thus … the wicked multitude usurped ecclesiastical authority,’ Attersoll railed, ‘and endeavoured to subvert the power of the Church-government, and to bring in a parity, that is, an horrible confusion.’ The wicked multitude of his own parish had done the same thing, as had others across the country. All around there were rebellions and usurpations, and there was a social as well as religious need for figures of authority. ‘Magistrates and rulers are needful to be set over the people of God,’ he wrote. They are the ‘father[s] of the country’. Similarly, though ministers of God like himself were no longer called padre, fatherhood was still their role: ‘The Office of the Pastor and Minister of God, is an Office of power and authority under Christ.’27