Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

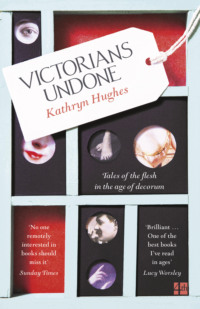

Kitabı oku: «Victorians Undone: Tales of the Flesh in the Age of Decorum», sayfa 2

1

Lady Flora’s Belly

I

It is the last week of June 1839, and a young woman lies dying in Buckingham Palace. Outside, in the grand mansions of Mayfair and the long, sweltering sweep of Piccadilly, the Season is winding down, and anyone who is anyone is getting ready to leave London in search of stiff sea breezes and creamy country air. But thirty-three-year-old Lady Flora Hastings is adamant that she will not make the long trip home to the Scottish Lowlands for what will surely be her last few days on earth. It is important that she dies here, in central London, in view of the gawping public and the equally ravenous press. Lady Flora ‘remains much in the same state’, the Standard assures its anxious readers. Lady Flora ‘is still in extreme and undiminished danger’, explains the Morning Post, which has come to feel a proprietorial claim on this whole terrible business. ‘This unfortunate lady is, we fear, sinking rapidly to the grave,’ murmurs the Bradford Observer, as if it were standing by the patient’s bed on the first floor of the palace, taking her pulse. If the Observer actually had been present, it would not have liked what it saw. Lady Flora is as thin as a skeleton and almost as bald, a discarded rag doll rather than a soft, solid woman in her prime. Still, what you find your eyes drawn to again and again is not the patient’s once-elegant neck, now stretched like twisted rope, nor even her scalp, which is a rucked patchwork of bristle and skin. No, what you notice is her belly, which thrusts obscenely from her sparrow frame. In fact, if it did not seem so unlikely, you would swear that Lady Flora is about to give birth.

One floor up, the twenty-year-old virgin Queen of England sits writing her journal, as she does every night. It is, Victoria declares, ‘disagreeable and painful’ to have a dying person in her home. Just this week she has been obliged – although only after much ‘gulping’, according to one hostile witness – to cancel the end-of-Season ball she was planning in the Throne Room. Now that the novelty of Victoria’s fairy-tale first year on the throne has worn off, a smart quadrille is the only thing guaranteed to restore a rosy flush to that boiled-egg face. Sharp-eyed commentators can’t help noting a ‘bold and discontented’ tone to everything the young Queen does now. It was she who first started the rumour that the unmarried Lady Flora Hastings was, to use the polite equivocation, ‘enceinte’. Or if Victoria wasn’t the originator of the scandal, she was certainly quick to take it up, batting it around the middle-aged matrons in her retinue, searching their faces to see which bits of the story could be made to stick. And, although the doctors have more or less scotched the possibility, there is still an outside chance that at the very last moment Lady Flora, whether dying or not (and, frankly, the Queen has her doubts), will suddenly produce a baby from under her virgin skirts.

To understand ‘the Lady Flora Hastings affair’, a constitutional crisis that threatened to end Queen Victoria’s sixty-three-year reign almost before it had begun, you need to go back to 1834. It was in February that year that Lady Flora Hastings, then twenty-eight, sailed into court life under false colours. Officially she had been appointed as lady of the bedchamber to Victoria’s widowed mother, the Duchess of Kent, with whom the fourteen-year-old then-Princess lived in a suite of grubby rooms at Kensington Palace. But from all the muttered corner conversations and sliding glances it hadn’t taken the teenage heiress presumptive to the British throne long to work out that Mama’s new lady-in-waiting was actually intended as a companion for herself. The problem was that Victoria already had a confidante – her beloved governess Louise Lehzen, to whose firm care she had been entrusted at the age of five. Lehzen had been the Princess’s staunch ally in her struggles with the infamous ‘Kensington System’, that regime of isolation and control designed to ensure that when Victoria came to the throne at the age of seventeen or so (her ageing uncle William IV could not last much longer), she would appoint her mother as her Regent before retiring to the schoolroom for a further five years. That would allow time for the Kent coffers to refill, for the Duchess to entrench her Coburgian clan at court, and for Sir John Conroy, the Duchess’s Comptroller, to establish himself as the real power behind the throne.

Baroness (Louise) Lehzen

Yet for all its strenuous intentions, the Kensington System had proved unequal to its crooked task. According to Conroy, who had devised the elaborate set of rules by which young Victoria was to be shielded from any influence that might lessen her mother’s or his own, Lehzen had turned out to be a snake in the grass. Hiding in plain sight, as governesses are apt to, Lehzen ‘stole the child’s affections’ and set Victoria ‘against her mother’. The climax had come in 1835, when the sixteen-year-old heir to the throne refused to sign the papers that a desperate Conroy and the Duchess waved in front of her, the ones that promised to make them her Private Secretary and Regent the moment she became Queen. And in return for Lehzen’s steely support throughout all the shouting, slamming of doors and spraying of spittle, Victoria had funnelled towards her governess the affection that should, for safety’s sake, have been spread more evenly. When Lehzen’s name appears in Victoria’s nightly journal, it is spontaneously lavished with ‘dearest’ and ‘best’. The Duchess, meanwhile, is simply ‘Mama’, with an occasional limp ‘dear’ dutifully careted in as an afterthought.

The Duchess and her Comptroller had shuffled their plot to substitute Flora Hastings for Louise Lehzen behind a cover story about the latter’s unsuitability as companion to the young woman who could at any moment be called to be Queen. Lehzen might be known by the nominal title of ‘Baroness’, but that hardly qualified a Hanoverian pastor’s daughter who chomped caraway seeds (the Victorian equivalent of chewing gum) to provide the social gloss required to turn a German dumpling who muddled her ‘w’s and ‘v’s into an English Rose. Or, indeed, into ‘the Rose of England’, which is what some of the more gushing prints insisted on calling the heiress presumptive to the British throne. Dinner guests at Kensington Palace had started to whisper how unfortunate it was that Princess Victoria had yet to master the knack of eating with her mouth closed, especially given her habit of stuffing it so full of food that she resembled a small, pouched rodent. By contrast, Lady Flora’s table manners – indeed everything about her – were exemplary. The eldest daughter of the late Marquess of Hastings was known to be naturally pious yet sufficiently worldly to belong to what the newspapers liked to call ‘the Fashionables’. From the late 1820s you might spot the tall, slender young woman gliding around the supper room at Almack’s or attending one of Queen Adelaide’s Drawing Rooms (her brother was a gentleman of the bedchamber), her graceful figure and modish outfit warranting a short admiring paragraph in the gossipy Morning Post.

The Duchess of Kent and her daughter Princess Victoria, 1834

Within days of Lady Flora’s arrival at the Kensington court-in-waiting on 20 February 1834, fourteen-year-old Princess Victoria had protested in the only way available to her, by taking to her bed. Over the next six weeks she ran through her habitual repertoire of headaches, backache, sore throat, ‘biliousness’ and a fever, which not only got her the concentrated attention of ‘dear Lehzen’, who was ‘unceasing … in her attentions and care to me’, but also handily kept Mama’s new lady and her long neck at bay. Still, Lady Flora could not be dodged for ever. As summer gave way to autumn the Duchess made it clear that wherever Victoria and Lehzen went, Lady Flora was to go too, like an elegant hobble. The new lady of the bedchamber gamely trailed the inseparable girl and governess as they huffed up and down Hampstead Heath for the sake of the Princess’s convalescence, whiled away the holiday months in a series of grubby rented houses on the south coast, and sat through I Puritani at the opera for what seemed like the hundredth time. And it was here, in these awkward triangular huddles, that young Victoria had first grown to loathe Lady Flora as a ‘spie’ who snooped on her most private conversations, quarried her most intimate thoughts and bore them back in triumph to Conroy and Mama.

In the end, though, the Kensington System was bested simply by one silly old man living longer than anyone thought possible. By the time William IV, he of the pineapple-shaped head, died in the early hours of 20 June 1837, Victoria had passed her eighteenth birthday and was constitutionally entitled to reign alone. In those first thrilling days of power she tore through the old Kensington court like a tiny Tudor tyrant bent on restoring her favourites and casting her enemies into outer darkness (the Tower, sadly, being no longer an option). Lehzen was put in charge of running the royal household and became Victoria’s ‘Lady Attendant’, while the Duchess, angling for the title of ‘Queen Mother’, was told sharply that the thing was impossible. Lady Flora was left in no doubt either that her services as a companion to the new Queen were not required, although nothing could be done about the fact that she was still a member of the Duchess’s household, and would be moving with her employer to Buckingham Palace. Mercifully left behind in Kensington for good were the hateful Conroy girls, Victoire and Jane, whom Victoria had been forced to endure for years as unofficial maids of honour. Like the ugly sisters at the end of the pantomime, the beanpole pair now withdrew from the stage, and could henceforth be heard squawking loudly in the local shops about how much the new Queen still depended on dear Papa.

Just four years earlier Victoria had been playing with her dolls, a collection of 130 adult female figures named after celebrity aristocrats of the day and dressed to perfection by Lehzen’s clever needle. Now, in their place, the new Queen assembled twenty-six real, breathing women to be her daily companions. At the head of the new household was the fashionable Duchess of Sutherland, whose fairy-tale title was Mistress of the Robes. Other senior ladies included Lady Lansdowne (socially awkward but keen to please), Lady Portman (nice but dull) and Lady Tavistock (plain but tactful). The more junior maids of honour included Miss Pitt (beautiful), Miss Spring Rice (annoyingly friendly with Lady Flora), Miss Paget (‘coaxy’ and ‘wheedly’), not forgetting Miss Dillon, who was said to be ‘wild’ and required careful handling. Less glamorous in every way was Miss Mary Davys, the daughter of Victoria’s former tutor and chaplain Dr George Davys, who now became Resident Woman of the Bedchamber and was, noted Victoria in her journal, ‘a very nice girl (though not at all pretty)’.

With the exception of Mary Davys, ‘the ladies’ were drawn from the pool of great Whig families that furnished Lord Melbourne’s current government. Lady Tavistock was sister-in-law to Melbourne’s ally, the doll-sized Lord John Russell; Lady Lansdowne was married to the Lord President of the Council; while Lady Portman’s husband, newly ennobled, was doing sterling service in the Upper House. To wait on the young Queen was an extension of a political way of life that billowed out from Westminster to the grand Whig townhouses of Mayfair and from there to the rolling blue-green acres of Woburn, Chatsworth and Bowood. A confidence exchanged over dinner at Buckingham Palace might end up, a year later, back at Westminster, wrapped in a bit of new legislation or tossed away as a knowing joke.

On 17 July 1837 Mary Davys left her family home for this ‘dream of grandeur’, gusted along by a handsome salary of £400 a year. But although she was now hobnobbing with ‘the rank and fashion of London’, Mary soon discovered that the life of a courtier was no less mundane than life in a sedate vicarage. On receiving your ‘daily orders’ each morning, you might find yourself called upon to accompany the Queen on a walk, to church or on a visit to blind, elderly Princess Sophia, still mouldering away at Kensington Palace. Alternatively, there might be some kind of official business: a factory inspection, perhaps, or a visit to an orphanage, or one of the quarterly ‘Drawing Rooms’. But whatever the setting, the rules remained the same. You were required to walk far enough behind her little Majesty so as not to throw her into shadow (she wasn’t even five feet tall, although she insisted that she was still growing), but near enough to be useful if she needed to hand you something: a limp posy that had been offered by a none-too-clean fist perhaps, or a shawl that was now surplus to requirements. Indeed, ‘shawling’ was the name one wearied veteran gave to the whole fiddle-faddle of spending your days as a glorified lady’s maid, one who didn’t even get cast-offs and tips to compensate for all those hours lost to blank-eyed tedium and aching calves.

The evenings, too, could be numbing. Being placed next to the very deaf Duke of Wellington meant spending hours either shouting or being shouted at. Having Lord Palmerston – aka ‘Cupid’ – as your neighbour required you to shuffle your knees under the table to avoid his hopeful pokes and squeezes. And sitting next to one of Her Majesty’s more leaden cousins – Prince Augustus, say – involved racking your brains until you found a subject on which the young man from Saxe-Coburg would venture more than a single syllable. Dinner over, you might find yourself corralled into interminable games of ‘schilling’ whist with the Duchess of Kent, whose impenetrably Germanic English required you to strain to catch her drift. Finally, the teenage Queen, able for the first time in her life to determine her own bedtime, insisted on everyone staying up until past midnight, which meant that the larks in the company spent two hours stifling yawns and trying not to glance too obviously at the clock.

‘You must accustom yourself,’ Lady Ravensworth advised her daughter on her appointment as maid of honour in 1841, ‘to sit or stand for hours without any amusement save the resources of your own thoughts.’ But it was your own thoughts that were often the problem. As Mary Davys quickly discovered, the vacancy at the heart of court life quickly filled up with gossip, intrigue and petty drama from which it was impossible to remain aloof. The fact that the senior ladies were mustered on a rota, coming into waiting for only several months of the year, should have allowed for a regular freshening of the atmosphere. But in reality it never felt like that. Life at court was rather like attending a select girls’ boarding school where lessons had been temporarily suspended and some of the older pupils were breasting the menopause.

Take the business of nicknames. The habit of giving people aliases had begun during the last years at Kensington. John Conroy was known behind his back as ‘O’Hum’, and stage-whispered comments were made about his origins in ‘the bogs of Ireland’. O’Hum in turn had flung back remarks about Louise Lehzen’s table manners, making reference to ‘the hogs from Low Germany’. Other tags were ostensibly more benign, although you could never be quite sure, especially in a bilingual court where meanings and intentions quickly skidded. Flora Hastings had long been known as ‘Scotty’. Another of the Duchess’s attendants, Lady Mary Stopford, was ‘Stoppy’. Miss Spring Rice was ‘Springy’. Newcomer Mary found herself called ‘Humphry’ after the inventor of Davy’s safety lamp, designed to protect workers in enclosed spaces from suffocation and sudden combustion. Given Mary’s role as the royal household’s peacemaker and go-between, this sounds about right.

Yet despite her determination to resist the ‘too attractive, too fascinating’ lures of court life, Mary Davys found herself dragged into the household’s increasingly toxic churn. During the interminable drawing-room sessions after dinner the Duchess of Kent made a point of trying to pump her former chaplain’s daughter for information about what the Queen was thinking and doing. (Where once the Duchess had slept in the same room as her daughter and monitored her every waking moment, now she was crammed into pointedly poor accommodation at the other end of the palace, and only got to see her when there were other people present.) And although Mary resisted the Duchess’s fishing expeditions as tactfully as she knew how by keeping the conversation fixed firmly on such neutral topics as the novels of Sir Walter Scott, she could not help feeling sorry for the middle-aged woman in the too-bright silks who complained that she was now treated ‘as nothing’. Banished to the far end of the long dining table with Lady Flora Hastings, the Duchess could be heard sighing theatrically about how horrible it was to see Victoria’s ‘pretty young face’ next to Lord Melbourne’s old one, night after night.

Actually, the Duchess had a point. Spending up to six hours a day with her Prime Minister, including dinner most evenings, Victoria had started to hang on Melbourne’s every word, gulping down his thoughts on such pressing matters as how to spell ‘despatches’ and why women pack more for a short trip than men. More delightful still was the retrospective sympathy he offered over her struggles with the trifecta of Mama, Conroy and Lady Flora. The girl who had been brought up by her governess to give nothing away was, within a few weeks, telling Melbourne all about ‘very important and even to me painful things’, including what she insisted on describing as the ‘torments’ of her Kensington ‘imprisonment’. And he in turn, a middle-aged widower who had recently lost his only child, found himself enchanted with his confiding little mistress.

Lord Melbourne, c.1839

The political diarist Charles Greville, watching the new reign from his vantage point as Clerk of the Council, reckoned that the young Queen’s feelings for her Prime Minister were ‘sexual, though She does not know it’. What struck Greville was the greed with which Victoria lapped up Melbourne – not just his jokes and his thirty years of political knowledge and his remnant good looks, but his thrilling romantic history. For not only was Lord Melbourne the widower of the doomed Lady Caroline Lamb, who had gone mad with love for Lord Byron, but just the previous year he had been accused of ‘criminal conversation’ in the divorce trial of the notorious Mrs Caroline Norton. One of the founding intentions of the Kensington System had been to insulate the Princess from exactly this sort of dirty talk, which had been the lingua franca of her uncles George IV and William IV’s courts. A cordon sanitaire had been thrown around the girl, and no man was allowed to approach, unless he happened to be a cousin from the Continent. Indeed, one aristocratic lady visitor, arriving at Kensington Palace to take tea with the Duchess and the Princess, had been taken aback to be told that her six-year-old son would have to wait outside in the carriage.

‘Susannah and the Elders’ (1837), by John Doyle, shows Victoria flanked by Lords Melbourne and Palmerston

All of which made this sudden access to men, and stories about men, quite thrilling. It wasn’t just Lord Melbourne, although he remained the sun of Victoria’s solar system. It was also the gentlemen in her household, each dedicated to anticipating her needs before she had registered them as the merest flicker. There was Mr Charles Murray, who was master of the household; Colonel Cavendish, the equerry; and Sir Robert Otway, the groom-in-waiting. One young man, pretty Lord Alfred Paget, had taken chivalry to the most elaborate heights. The gallant young equerry kept a picture of the Queen in a locket around his throat, and made sure that his golden retriever, Mrs Bumps, was similarly attired. During the court’s periodic residences at Windsor all the gentlemen, including Lord Melbourne, wore ‘the Windsor Uniform’, an olden-days rig of breeches, buckles and cutaway coat with scarlet facings. It was like a fairy tale. It was a fairy tale.

II

If the Duchess of Kent appeared to have deflated to half her former size in the move to Buckingham Palace, her favourite lady-in-waiting had become more sharply defined. It was as if someone had outlined Lady Flora with a firm lead pencil: wherever you looked she was always there, ‘spying’ on the company and making her sharp little jokes. All of which was ironic when you considered that her status had tumbled along with her employer’s. At Kensington Flora had prided herself on keeping her desk as well-organised as ‘a Secretary of States’, as befitted a key member of the court-in-waiting. But with Victoria ascending to the throne on 20 June 1837 as a legal adult, Flora had been demoted overnight to the position of paid companion to the middle-aged widow of a minor Prince. Yet if she felt the humiliation, she said nothing. Instead she continued to behave as she always had: ‘restrained and uncommunicative’, according to Mary Davys, who was shaping up to be as good a ‘spie’ as Lady Flora herself. While the other court ladies popped in and out of each other’s sitting rooms to while away the endless hours with drawing, sewing, practising magic tricks and reading the Bible, Lady Flora made it quite clear that she was not open to such invitations: ‘we never think of going to her room’, explained Mary; ‘she does not wish it’.

At the end of April 1838 Lady Mary Stopford, about to finish her current period of waiting on the Duchess, was getting ready to hand over to Lady Flora, who had been away from court since the previous August. For the first time since their positions had been so dramatically reversed during the first few hours of the new reign, those two old foes, Baroness Lehzen and Lady Flora Hastings, would be obliged to live alongside each other once more. Lady Mary Stopford took advantage of a brisk carriage ride around Windsor Great Park to give Mary Davys ‘some hints about my conduct to Lady Flora Hastings, and said now was the time that I might by a little tact be useful to the Baroness and Queen whom she will try to annoy’. Twenty-two-year-old Mary, though, was not optimistic about her chances of neutralising ‘Scotty’s’ astringent reappearance at the palace. ‘The poor Baroness will be much plagued, I fear!’ wrote the worried clergyman’s daughter, ‘but we will hope for the best.’

Victoria, meanwhile, was not hoping for the best at all. On 18 April the young Queen confided to ‘Lord M’ how much she ‘regretted’ the fact that Lady Flora would soon be back in waiting, since she was, and always had been, the ‘Spie’ of her mother and Sir John. Lord M pronounced himself ‘sorry’ at the news too, and proceeded to pluck from his teeming memory a scurrilous account of Lady Flora’s antecedents. In response to the Queen’s pointed enquiry as to whether the late Marquess of Hastings had been a man of any talent, Lord M said emphatically not: ‘he could make a good pompous speech and gained a sort of public admiration’, but ‘“he was very unprincipled about money”’. Five days later, and with the ‘odious’ Lady Flora’s arrival now imminent, Victoria returned to the subject that had begun to obsess her: ‘I warned him against … [Lady Flora], as being an amazing Spy, who would repeat everything she heard, and that he better take care of what he said before her; he said: “I’ll take care”; and we both agreed it was a very disagreeable thing having her in the House. Spoke of J.C., &c.’

This segue in Victoria’s journal from Lady Flora to ‘JC’, trailed by that insinuating ‘et cetera’, was nothing new. During the Kensington years she had been forced to watch as Lady Flora and Sir John plotted ostentatiously in corners to get Lehzen – whom they snootily dubbed ‘the nursery governess’ – dismissed from Kensington Palace and bundled back to Hanover. But now, with that battle definitively lost, the fact that the conspirators were still spending so much time together was beginning to make people talk. Conroy’s constant presence at Buckingham Palace could be explained away by the fact that, while he had been dismissed from the Queen’s household (or rather, never appointed), he was still her mother’s Comptroller. To emphasise the point, he had taken to travelling every day from his Kensington mansion to the Duchess’s cramped suite in what was still referred to as the ‘new palace’, where he got under the feet of her visiting Coburg relatives and provoked some of Victoria’s more nimble ladies to dive for cover whenever they heard his booming voice on the stairs. There was, though, one room where he could always be sure of a warm welcome. Even Mary Davys, who tried so hard to keep her mind on ‘subjects of higher importance’, allowed herself to drop hints in her letters home. The real reason, she explained, why she would not think of knocking on Lady Flora’s door was because ‘I should be afraid of meeting Sir John who is there a good deal.’

Sir John Conroy, 1837

To those who wondered what on earth the stand-offish Scotswoman and the noisy Irishman had in common, it was doubtless pointed out by more sober-minded courtiers that, actually, their two families had been allies for decades. Conroy’s brother had been the Irish-born Marquess of Hastings’s aide de camp during his governorship of India from 1813 to 1823. The two men had bonded in adversity when both had been implicated in a banking scandal that had left their reputations in tatters – hence Lord Melbourne’s jibe about Hastings being ‘unprincipled about money’. In addition, Conroy’s anger at being let down by the Crown chimed with Flora’s own family mythology. Twenty years earlier her father had been left bankrupt after lending money to the Prince Regent. Lord Hastings’s final years had been spent trying to scrabble back his fortune by accepting the Governorship of Malta, a position that smacked of desperation for a man who had once been spoken of as a future Prime Minister.

So Lady Flora and Sir John had ample reason to bond over the way ingrate monarchs habitually swindled their most devoted public servants. In a letter written at the end of the first summer of the new reign, Conroy had spewed out his bile to Flora at how the Queen and Melbourne were currently batting away his claims to a peerage. Flattered by being taken into his confidence, the usually ‘uncommunicative’ Flora responded with what sounds remarkably like passion: ‘I feel that to know how deeply that letter touched me, you would require to see into my heart – I feel all its nobleness, all its generosity; of how kind in you thus to allow me to enter into your feelings to think me worthy of sharing them, to tell me I can be a comfort to you!’ Lady Flora is adamant that Conroy is ‘not treated as you deserve’, and that he ‘suffers for his integrity’. However, ‘these are days when the injustice of a court can influence only its own petty tribe of sycophants. You have met with much ingratitude & doubtless you will meet with more, but there are true hearts still left.’ Sir John, she concludes, is her ‘dearest friend’. From here her thoughts scramble to the fact that ‘in much you resemble my father. In much also your fate bears some analogy to his’, before finishing with ‘your reward is in Heaven’, which is probably not what Conroy was hoping to hear. At this point the usually ‘restrained’ lady of the bedchamber signs off to ‘my beloved friend’, calling herself simply ‘Flora’.

Around the time Lady Flora came back into waiting, Conroy unleashed the full blast of his anger towards Victoria for withholding the things that made his black heart beat faster: power, a peerage, a public stage on which to strut and bluster. By 11 June 1838, a fortnight before the coronation, to which he was pointedly not invited, Conroy had filed a charge of ‘criminal information’ against The Times. In effect he was suing the paper for claiming that he had siphoned off money from the Duchess of Kent’s bank account. Such was the tinderbox of bad feeling between the two households at the palace that Conroy suspected Victoria of having planted the piece herself. The list of witnesses to be called included Lord Melbourne, the Duchess of Kent and a jittery Baroness Lehzen, who had turned to jelly at the prospect of giving evidence at the Queen’s Bench. Which is exactly, of course, what Conroy had hoped for.

In the end none of the witnesses appeared. All the same, the Times business provided the nagging mood music to Victoria’s post-honeymoon period as Queen, a grinding reminder that the ‘torments’ of the Kensington years had not gone, but were waiting to bloom in strange new shapes. ‘I got such a letter from Ma., Oh! oh! such a letter!’ recorded a blazing Victoria in January 1838, reluctant to commit further details to paper, convinced that someone was reading her journal and blabbing its contents around the court. A few weeks later the Duchess attempted to patch things up by writing Lehzen a conciliatory note, but when that fell flat she retreated into her old nest of grievances, and added a few new ones for good measure. She complained that her ‘childish’ daughter was rude to her in front of other people and always took the opposite side in any argument. She put it about that Victoria had broken her heart, and paraded around déshabillée to prove the point. She spoiled Victoria’s nineteenth birthday that May by slyly presenting her with a copy of King Lear, and then sulked all the way through the anniversary ball. She believed John Conroy when he told her there was a plot to get rid of her, but couldn’t understand why Victoria continued to be so hostile to the man who was dragging the royal household through the courts. There had never, concurred Lord M, been a more foolish woman, not to mention a more untruthful one. Mind you, he added with a knowing look, the Duchess was fifty-two, which everyone knew was an ‘awkward’ age for a woman.