Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

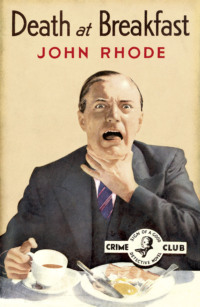

Kitabı oku: «Death at Breakfast»

JOHN RHODE

Death at Breakfast

Copyright

COLLINS CRIME CLUB

an imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by Collins Crime Club 1936

Copyright © Estate of John Rhode 1936

Cover design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 1936, 2017

John Rhode asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008268756

Ebook Edition © October 2017 ISBN: 9780008268763

Version: 2017-09-08

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Prologue

Chapter I: A Mishap While Shaving

Chapter II: Clues in Abundance

Chapter III: ‘Stanley Fernside’

About the Author

About the Publisher

Prologue

Victor Harleston stirred uneasily. He grunted, then opened his eyes. Was he awake? Yes, he thought so. He stretched himself, to make quite sure of the fact.

It was still dark behind the closed curtains, on this January morning. Too dark for Harleston to see the time by his watch, which lay upon the table beside his bed. He was too lazy to stretch out his hand and switch on the light. Instead of this, he lay still and listened.

Very little noise came to him from without the house. Matfield Street was a backwater, lying not far south of the Fulham Road, and comparatively little traffic passed along it. One or two early risers were evidently about. Harleston could hear the hurried tap of a woman’s heels upon the pavement. This passed and gave place to a popular tune, whistled discordantly. A boy on a bicycle, probably. Considering that the window of his bedroom looked out at the back of the house, it was surprising how distinctly one could hear the noises from the street, Harleston thought idly.

But these were not what he was listening for. His ears were tuned to catch a familiar sound from within the house. Ah, there it was! A rattling of crockery. Janet would be along soon with his early tea. Harleston pulled up the eiderdown a few inches, and composed himself for a few minutes doze.

Then, suddenly, his memory returned, and in an instant he was wide awake. It was the morning of January the 21st, the day which was to make him rich! No more dozing for him now. Rather an indulgence in luxurious anticipation. Before the day was out, he could be his own master, if he chose. He hadn’t decided yet what he should do. Better not throw up his job at once. People might wonder. On the whole, it would be best to wait until the Spring, then take a long holiday and consider the future. There was no earthly need for a hurried decision.

He heard a door slam, somewhere downstairs, and then steps approaching his room. Janet, with the tea. It must be half-past seven.

Then the expected knock on the door, and a girl’s voice, ‘Are you awake, Victor?’

‘Yes, come in,’ he replied.

The door opened, and the girl placed her hand on the switch, flooding the room with light. She wore a gaily coloured apron, and was carrying a tray. Seen even this early in the morning, she was not unattractive. Full, graceful and unhurried in her movements. A slim figure, with her head well set upon her shoulders. Her face was certainly not pretty, but, on the other hand, it could not be described as ugly. Plain Jane, she had been called at school. And the nickname aptly described her. Janet Harleston was plain, without anything special about her face to capture the attention.

If you looked at her twice, you did so the second time because your curiosity was aroused. You wondered if her expression was natural to her, or whether something had occurred that moment to cause it. You noticed the sullen droop of her lips, the hard, unsympathetic look in her grey eyes. A sulky girl, you would have thought.

Her behaviour on this particular morning would have strengthened that impression. She put the tray down upon the table by Victor Harleston’s bed, and left the room without a word.

He made no effort to detain her. His mind was too full of plans for the future to find room for trifles. He raised himself to a sitting position, blinking in the sudden light. Seen thus, his face appearing above his brightly striped pyjamas, he was definitely unlovely.

Victor Harleston was a man of forty-two, and at this moment he looked ten years older. His coarse, heavy face was wrinkled with sleep, and his sparse, mouse-coloured hair, already beginning to turn grey, had gathered into thin wisps. These lay at fantastic angles on his head, disclosing unhealthy looking patches of skin. What could be seen of his body was flabby and shapeless. His eyes were intelligent, almost penetrating. But there was something malefic, non-human about them.

He yawned, disclosing a set of discoloured teeth, in which were many gaps, and looked about him. Janet was still upset, then. She hadn’t troubled to draw the curtains or light the gas-fire. Well, he couldn’t help her troubles. She’d get over them in time. She’d have to.

This last reflection brought a grin to his face. He loved to feel that people had to do what he wanted. At present, the number of such people was disappointingly small. Janet, and a few juniors at the office. It galled him to think that, up till now, he had himself had to do what his employer wanted. Up till now! Money was a precious thing, to be carefully hoarded. There was only one way in which a rational man was justified in spending it. The purchase of freedom for himself, and of servitude for others.

Still, he would have to make up his mind about Janet. He might make her an allowance, and tell her to go to the devil. But the prospect of parting with any of the fortune now within his grasp was repugnant to him. Why should he make Janet an allowance? Why part with one who was, after all, an efficient and inexpensive servant? He would only have to replace her, and the money spent on the allowance would be utterly thrown away, bringing him no benefit. Yes, that was the plan. He would stay here, in this house which was his own and suited him. But he wouldn’t spend the rest of his life earning money for other people. He would enjoy himself, and Janet should continue to look after him. But she must never be allowed to guess at his sudden access of fortune. That was a secret to be hugged to his own breast.

As for her temper, that had never troubled him yet, and it was not likely to now. She was too dependent upon him to let her ill-nature go to extremes. Dependent upon him for every mouthful she ate, every shred she wore. It was a delicious thought. He could dispose of her as he pleased. And it pleased him that she should remain and keep house for him. Victor Harleston poured himself out a cup of tea, added milk and sugar, and left it to cool.

He resumed his interrupted train of thought. No need to take seriously her threat of the previous evening. She would leave him, and go and stay with Philip until she found a job for herself! Not she! She knew too well which side her bread was buttered to do a silly thing like that. Jobs that would suit her couldn’t be had just for the picking up. There was only one job she was fitted for, that of a domestic servant. And what would Philip, with his high-flown ideas, say to that? It was all very well for the young puppy to encourage her. He wasn’t earning enough to keep her, that was quite certain. And he had a perfect right to forbid Philip the house, if he wanted to.

Victor Harleston drank his tea, and got out of bed. His first action was to draw the curtains. A sinful waste to use electric light if he could see to dress without it. Yes, it was a bright morning, clear and frosty. He switched off the light. Then he took a cigarette from a box which stood on his chest of drawers, and put the end of it in his mouth. He found the box of matches which he always kept hidden in a drawer, underneath his handkerchiefs. He struck a match, turned on the gas-fire, and lighted it. With the same match he lit his cigarette. No sense in using two matches when one would serve. Then he put the box back in its accustomed place.

As he did so, a sheet of paper which he had placed on the dressing table the previous evening caught his eye. It was a business letter. He read it over again, and smiled. All right. He had not the slightest objection to receiving something for nothing. He would try the experiment, right away.

Standing in front of the gas-fire, warming himself, his thoughts reverted to his impending fortune. He picked up a pencil from the mantelpiece, and with it made a few calculations on the back of the letter. The resulting figures seemed to please him, for he nodded contentedly. Quite a lot of money, if carefully husbanded.

He folded the letter in half, and tore it across. Then put the two halves together, folded them as before, and once more tore them across. With each of the four scraps of paper thus produced he made a spill. These he added to a bundle of similar spills which stood in a vase. No sense in wasting matches, when with one of these one could light a cigarette from the gas-fire.

He took his dressing-gown from a hook behind the door, put it on, and went along to the bathroom.

I

A Mishap While Shaving

1

Doctor Mortimer Oldland, though no longer young, was still full of energy. He would tell his patients, sometimes rather acidly, that hard work had never killed anybody yet. It certainly showed no signs of killing him. His extensive practice in Kensington left him very little leisure. But he always seemed ready at any moment to tackle a fresh case or to persevere with an old one.

He believed in early rising, summer or winter. By half-past eight on the morning of January 21st he had finished his breakfast, and was sitting over the fire consulting his case-book. As the clock struck the half hour, the door opened, and the parlourmaid appeared. ‘There’s a lady called to see you. sir. She says it’s urgent.’

‘It’s always urgent when ladies call at this hour,’ replied Oldland calmly. ‘I suppose she has brought the usual small boy, suspected of swallowing a sixpence?’

‘No, sir. She’s alone, and seems in a terrible state. She was too upset to tell me her name. And I don’t think I’ve ever seen her here before, sir.’

‘All right. I’ll see what I can do for her.’ Oldland put down his case-book, and walked into his surgery.

He was confronted by a distraught woman, a perfect stranger to him. ‘Oh, Doctor!’ she exclaimed, as soon as he appeared. ‘Can you come round at once? My brother has been taken very ill, and I don’t know what to do for him.’

Oldland’s experience had made him a pretty fair judge of character. She did not seem to him the sort of woman who would fly into a panic over nothing. ‘I’ll come,’ he replied shortly. ‘Where is your brother?’

‘At home, 8 Matfield Street. It’s quite close …’

‘So close that it will be quicker to walk there than ring up for a taxi. And you can tell me the details as you go.’

He picked up his emergency bag, and they set off, Oldland walking at his usual smart pace, the girl, for it was evident that she was quite young, half running to keep up with him. In broken words she described the symptoms. Her brother had come down to breakfast as usual, but complaining of not feeling very well. He had drunk a cup of coffee, but had been almost immediately sick. He had complained of being terribly giddy, and had seemed unable to walk. On leaving the dining-room, he had collapsed on the floor of the hall, where he lay, unable to speak or move.

‘I see,’ said Oldland. ‘We’ll see what we can do for him. By the way, I don’t think I caught the name?’

‘Harleston. I’m Janet Harleston, and my brother’s name is Victor. He’s only my half-brother, and he’s a good deal older than I am. I keep house for him. I’ve never known him like this before. He’s always perfectly well.’

Oldland asked no more questions, and they covered the remainder of the distance in silence. The front door of number eight Matfield Street was standing ajar. Janet Harleston ran up the half-dozen steps which led to it, and pushed it open.

Oldland followed her into a narrow, linoleum-laid hall. He had no need to inquire the whereabouts of his patient. Victor Harleston lay huddled on the floor. At a first glance Oldland saw that he was completely unconscious. He examined the patient rapidly, then took a syringe from his bag and administered an injection. ‘Is there a sofa handy?’ he asked sharply.

Janet was standing by, watching him anxiously. ‘Yes, in the sitting room,’ she replied. ‘Just through this door.’

‘Is there a maid in the house?’

‘No, my brother and I live alone. We have a charwoman, but she doesn’t come until the afternoon.’

‘That’ll be too late. He’s a heavy man, and I hardly think we could manage him between us. Will you run out, please Miss Harleston, and fetch a policeman. There’s one at the corner of the Fulham Road, I noticed him as we passed. Tell him I sent you. He’s sure to know my name.’

She ran out obediently, and Oldland resumed his examination of the patient. Victor Harleston, his toilet completed, was more presentable than he had appeared in bed. His hair was brushed and neatly parted, and his clothes, if not smart, were clean and nearly new. But he had apparently cut himself while shaving, and the patch of sticking-plaster adhering to his cheek was scarcely an ornament. Oldland, holding his pulse, shook his head ominously.

Within a couple of minutes Janet returned with a policeman. He and Oldland exchanged nods of mutual recognition. ‘This young lady asked me to come along, sir …’ he began.

‘Yes, that’s right, Carling.’ Oldland cut in curtly. ‘Poor fellow. Taken ill. I want to get him on to the sofa next door. You take his shoulders, and I’ll take his legs. That’s right.’

The two men carried Victor Harleston into the sitting-room, Janet following them. The unconscious man having been deposited on the sofa, the policeman turned to go. But Oldland detained him. ‘Don’t run away for a moment’ he said. ‘I may want you to help me move him again presently. Miss Harleston, I want you to run over to my house again. When the parlourmaid opens the door, ask her to give you the small black case which is lying on the mantelpiece in the surgery. The black one, mind, not the red. And bring it back here as soon as you can.’

For the second time she ran off, and Oldland listened to her footsteps as they descended the front steps. As though to satisfy himself of her departure, he went to the front door and watched her till she disappeared round the corner of Matfield Street. Then he came back to the policeman. ‘Your turn to run errands, now, Carling,’ he said. ‘There’s no telephone in this house, that I can see. Slip round to the nearest box, and ring up Scotland Yard. Ask for Superintendent Hanslet. He knows me well enough. And tell him that there’s a job waiting for him here. I’ll stop in the house until he comes, or sends somebody else. Got that?’

‘Yes, sir,’ replied Carling. ‘Will you want me again?’

Oldland shook his head. ‘Neither you nor I can do any more for this poor chap. He’ll be dead within the next few minutes.’

Left alone with his patient, Oldland’s expression changed. His usual rather cynical smile gave place to a look of sterness such as few of his friends had seen. He picked up the inert wrist once more, and remained holding it until the irregular pulse had fluttered into lifelessness. Then, with a sharp sigh, he composed the body in a natural attitude, and stood for a moment looking at it as though he half expected the departing soul to reveal its secret. At last he shrugged his shoulders, and abruptly left the room.

He had already taken in the arrangement of the house. Two doors opened off the hall. The one nearest the front was that of the sitting-room, into which Victor Harleston had been carried. The second door was ajar, revealing a table laid for breakfast. Evidently the dining-room. At the end of the hall was a flight of steps leading downwards to the basement, and another flight leading upwards to the first floor. Oldland hesitated for a moment, then walked into the dining-room.

It was adequately furnished with objects of a peculiarly ugly type. A heavy, clumsy looking table stood in the middle of the floor, which was covered with a rather worn carpet. On the table was spread a white cloth, apparently fresh from the wash. The room contained a set of dining-room chairs, two of which had been drawn up to the table. One of these had been overturned, and lay on its side. The other, on the opposite side of the table, seemed to have been pushed back hurriedly.

Oldland inspected the preparations for breakfast, being careful, however, to touch nothing. In front of the overturned chair was a respectable meal. A couple of fried eggs and two rashers of bacon on a plate. These had not been touched, and were now cold and greasy. The knife and fork lying beside the plate were not soiled. A second plate, on which was a piece of toast, broken in half, but otherwise untouched, and a pat of butter. A cup, which had evidently been drunk from, empty but for some dregs of coffee at the bottom.

The meal laid at the other side of the table was more modest. No eggs and bacon, merely a plate with toast and butter, some of which seemed to have been eaten. A cup of coffee, full and untouched. At this end of the table stood a coffee-pot. Oldland, anxious to disturb nothing, did not lift the lid. Beside it stood a jug, about a third full of milk which had once been hot. In the centre of the table was a toast-rack, with four pieces of toast still in it. There was also a butter dish, with a few pats of butter, and a cruet with salt, pepper, and mustard.

At one end of the room was a recess, with a window looking out at the back of the house, over an unkempt patch of garden. In this recess was a roll-top desk, with the top closed. Oldland noticed that the key was in the lock. This key was on a ring with three others of various kinds. Two of these were Yale keys.

Oldland, who had quick ears, heard the sound of hurried footsteps on the pavement. He returned to the hall, in time to confront Janet Harleston as she entered the house. ‘I’m sorry, Doctor,’ she said breathlessly. ‘But the parlourmaid said she couldn’t find the black case anywhere.’

‘No, I’m afraid you had your trouble for nothing. Miss Harleston,’ Oldland replied. ‘It was in my bag all the time. I found it just after you had gone.’

‘Oh, I’m so glad!’ she exclaimed. ‘How’s poor Victor? Is he any better?’

‘I’m sorry to say that your brother is dead, Miss Harleston,’ replied Oldland, with what seemed cruel curtness.

But amazement, rather than grief, appeared to be the effect caused by this bold statement. ‘Dead!’ she exclaimed incredulously. ‘But he was perfectly well when I took him his tea at half-past seven.’

‘That may be, Miss Harleston. You understand that, under the circumstances, I cannot give a death certificate, and that I shall have to communicate with the coroner?’

She shook her head helplessly. ‘I don’t know anything about these things, Doctor. Does that mean there’ll be an inquest?’

‘I’m afraid so. In any case, arrangements will have to be made to take the body to the mortuary. Have you any other relations alive, Miss Harleston?’

‘My mother and father are dead. But I have another brother. Philip, who lives in Kent. He’s my real brother, a year older than I am. He was here to supper yesterday evening. I’d better send him a wire to come up at once, hadn’t I?’

‘Plenty of time, plenty of time’ replied Oldland absently. He glanced at his watch. Past nine o’clock! His car and chauffeur would be waiting for him. He had a long round of visits to pay that morning. But he couldn’t leave this sinister house, yet. It was a damnable nuisance. ‘What was your brother’s occupation?’ he asked abruptly, more for the sake of continuing the conversation, than because he felt any interest in the matter.

‘He was a clerk in an accountant’s office. Slater & Knott is the name of the firm. Their offices are in Chancery Lane. Victor had been with them for years.’

‘Had he many friends in London?’

She shook her head. ‘No, Victor wasn’t the sort to make friends. He … Oh!’

Janet Harleston broke off with a sudden exclamation. She seemed suddenly to have remembered something, and Oldland glanced at her with a faint renewal of interest. ‘You were going to say?’ he suggested.

‘I was going to say that as far as I know, he hadn’t any friends, and then I remembered the man at the door, when I went to fetch you. I’ve been so upset, that I never thought of him again until this moment.’

Oldland might have pursued the subject, but at that moment the door bell rang insistently. ‘I’ll answer it,’ he said. ‘I expect it’s somebody for me.’ He walked swiftly to the door and opened it. On the threshold stood Superintendent Hanslet himself. ‘Morning, Doctor!’ he exclaimed cheerfully. ‘What’s the matter here?’

Oldland made no reply, but drew him inside and propelled him into the sitting-room. Janet, motionless in the hall, watched them with wide-open, frightened eyes, but said nothing. It was not until he and Hanslet were standing together in front of the sofa that Oldland spoke. ‘That’s what’s the matter,’ he said curtly.

Hanslet took a step forward, and bent over the body. ‘Dead?’ he asked.

‘Dead,’ replied Oldland grimly. ‘I was called in, and reached here at five-and-twenty minutes to nine. The man was then alive, but his condition was hopeless, and he died a few minutes later.’

‘What did he die of?’ asked Hanslet suspiciously.

‘Acute poisoning of some kind. And it appears that he lived alone with his half-sister, the girl you saw in the hall just now. The rest is up to you. I’ve got my work to attend to. You know where to find me if you want me.’

And before Hanslet could protest, he had slipped out of the house.

2

The superintendent shrugged his shoulders. He had always considered Oldland a bit eccentric, though he fully recognised his abilities. The two men had been acquainted for some few years.

Though Hanslet continued to stare at the body for some few moments, he did so more out of curiosity than in the hope of learning anything from it. He was fully prepared to accept Oldland’s statement. The problem before him would be simply expressed. The task of the police was to find out how the poison had been administered, and by whom.

Hanslet turned swiftly on his heel, and left the sitting-room, to find Janet still rooted to the spot where he had last seen her. ‘Allow me to introduce myself,’ he said. ‘I am Superintendent Hanslet of the Criminal Investigation Department. Acting upon information received, I have come here to make inquiries. To begin with, may I ask you your name?

She started, as though his words had awakened her from a deep reverie. ‘My name?’ she replied. ‘Janet Harleston.’

‘And the dead man was your brother?’

‘My half-brother, Victor Harleston. My father married twice. Both he and my mother have been dead for some years.’

‘You and your half-brother lived here alone?’

‘Yes. My father left the house to Victor. I stayed with him to look after him, since he was not married.’

‘I see. Now, will you tell me what you can of your brother’s illness? Everything that you can remember, please. But we need not stand here. I expect you would like to sit down?’

She led the way into the dining-room, and sat down stiffly upon one of the chairs which stood against the wall. Hanslet seated himself beside her. Before them were displayed the remains of the interrupted breakfast.

Janet began to speak without emotion, as though she were describing some remote event, entirely unconnected with herself. ‘I took him up his cup of tea at half-past seven, as I always do. He was all right then. I’m sure he was, for he looked just the same as he always did. I put his tray down by his bed …’

Hanslet interrupted her. ‘One moment, Miss Harleston. Did you speak to your brother when you took him his tea?’

‘I asked him if he was awake, before I opened his door, and he answered me.’

‘You didn’t ask him how he was, or any similar question?’

‘No,’ she replied sharply. ‘I didn’t speak to him while I was in his room.’

The tone of her voice did not escape Hanslet. It was clear to him that brother and sister had not been on the best of terms. But he did not comment on this. ‘What happened next?’ he asked.

‘I don’t know. I went down to the kitchen to get breakfast. It was a little after eight when I brought it in here. Victor came down a few minutes later. I saw that he looked rather pale, and I noticed that he had a piece of sticking-plaster on his face. I asked him if he had cut himself shaving, and he said something about any fool being able to tell that, since he wasn’t in the habit of putting plaster on his face to improve his appearance. I saw that he was as grumpy as usual, and didn’t say any more.’

Hanslet made a mental note of that phrase, ‘as grumpy as usual.’ ‘You had no reason to think that your brother was seriously ill?’ he asked.

‘Not for a few minutes. I poured out his coffee and passed it to him. Usually he eats his breakfast and then drinks his coffee. This morning he took a piece of toast and a pat of butter, but though he broke the toast in half he didn’t eat any of it. And he didn’t eat any of the eggs and bacon I had done for him, either. He seemed impatient for his coffee to get cool, and, as soon as he could, he drank it all off at once.’

‘Had he previously drunk the cup of tea which you had brought him?’

‘I don’t know. I haven’t been up to his room since. I saw that his hand shook as he held the coffee-cup, and I wondered what was the matter. After he had drunk his coffee, he sat for a minute or two in his chair, twitching all over. Then he got up, as though he was so stiff that he could hardly move. He was so clumsy that he upset his chair. Then he staggered to the door, waving his arms and trying to speak. He was very sick as soon as he got into the hall, and then he swayed for a moment, and fell down flat. I ran out to him, and saw that he was very ill. He didn’t seem able to move, and he couldn’t speak. I thought he had a stroke, or something. So I ran out at once to fetch the doctor.’

‘Is Doctor Oldland your usual medical attendant?’

‘Oh, no. We had no regular doctor. Nobody has been ill in the house since my father died, and the doctor who attended him has gone away now. But I had often noticed Doctor Oldland’s plate when I was out shopping, and as he lives quite close, I went to him.’

‘Since there was nobody else in the house, you had to leave your brother alone while you went for the doctor?’

A puzzled look came into her face. ‘That’s the funny part about it,’ she said, using the adjective in its commonly perverted sense. ‘I opened the front door and ran out, almost colliding with a man who was coming up the steps. He said, “Excuse me, are you Miss Harleston? I’m a friend of your brother’s.” I told him that my brother had been suddenly taken ill, and that I was just going for the doctor. He replied that he would stay with him while I was gone. I ran on towards Doctor Oldland’s, and I was so upset about Victor that I never gave the man another thought.’

‘But you and Doctor Oldland found him when you came back, I suppose?’

‘No, that’s the funny thing about it. We didn’t, there was nobody here.’

‘Are you sure that this man actually entered the house?’

She hesitated. ‘I’m almost sure. You see, I was in a desperate hurry, and only stopped on the steps for a moment when he spoke to me. I feel pretty certain that he walked through the front door as I ran away, but I didn’t look back to see what had become of him. I’m sure I didn’t shut the door, and Doctor Oldland and I found it ajar when we got back here.’

‘I gather that this man was a stranger to you, Miss Harleston?’

‘I had never seen him before. He said he was a friend of my brother’s, which would have surprised me if I had had time to think, for I didn’t know that Victor had any friends. Oh! I’ve just thought! Perhaps he meant that he was a friend of Philip’s.’

‘Philip?’ Hanslet repeated inquiringly.

‘Yes, my real brother. He was here to supper last night, and perhaps this man thought that he had stayed for the night.’

‘Can you give any description of this man?’

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.