Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

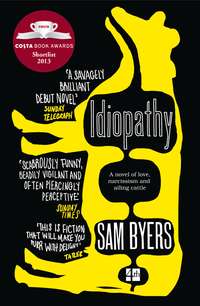

Kitabı oku: «Idiopathy»

Table of Contents

Title Page

Comparatively recently, during …

Daniel was in …

The café in …

A typical argument …

In Katherine’s mind, …

‘Love you darling. …

Nathan’s parents, as …

In Angelica’s absence, …

The feeling of …

Acknowledgements

Copyright

About the Publisher

noun

A disease or condition which arises spontaneously or for which the cause is unknown.

ORIGIN late 17th cent.: from modern Latin idiopathia,

from Greek idiopatheia, from

idios ‘own, private’ + -patheia ‘suffering’.

Ubi pus, ibi evacua.

Comparatively recently, during a family function about which Katherine’s mother had used the term three-line whip, but which Katherine’s sister had nevertheless somehow avoided, Katherine’s mother had shown a table of attendant relatives the photographs she kept in her purse. The relatives were largely of the aged kind, and their reliable delight in photos was a phenomenon Katherine had long been at a loss to understand. As far as she was concerned, ninety per cent of photographs (and relatives) looked the same. One grinning child was much like the next; one wedding was indistinguishable from another; and given that the majority of her family tended to holiday in depressingly predictable places, the resultant snaps of their trips abroad were fairly uniform too. So while the other relatives – Aunt Joan and Uncle Dick and their oddly wraith-like daughter, Isabel, plus two or three generic wrinklies who Katherine dimly remembered but with whom she had little interest in getting re-acquainted – cooed and hummed at the photos the way one might at a particularly appetising and well-arranged dessert, Katherine remained quiet and shuttled her eyes, as she so often did on these occasions, between the face of her mother and that of her watch, neither of which offered any reassurance that the event would soon be over.

Katherine’s mother’s purse, unlike the hands that held it, was smooth and new; recently purchased, Katherine happened to know, at Liberty, where Katherine’s mother regularly stepped outside her means.

‘What a lovely purse,’ said some removed cousin or other, clearly aware that any accessory Katherine’s mother produced in public had to elicit at least one compliment or else find itself summarily relegated to one of the sacks of abandoned acquisitions that she deposited with alarming regularity at the local charity shop. It struck Katherine that if the relatives had only shown a similar sense of duty when it came to the men in her mother’s life, her mother might be living in quite different circumstances.

‘Isn’t it darling?’ said Katherine’s mother, true to form. ‘Liberty. An absolute snip. Couldn’t resist.’

The photos were remarkably well-preserved considering that Katherine’s mother treated the majority of objects as if they were indestructible and then later, peering forlornly at their defunct remains, bemoaned the essentially shoddy nature of modern craftsmanship.

‘Look at these,’ said Katherine’s mother, referring to the photographs in exactly the same tone of voice as she’d used when discussing the purse. ‘Aren’t these just lovely?’

She passed round the first picture – a passport-sized black-and-white of Katherine’s sister Hazel clasping a flaccid teddy. With its rolling eyes and lack of muscle tone, the little creature looked like it had been drugged, lending Hazel (in Katherine’s eyes at least) the appearance of some sinister prepubescent abductor.

‘The teddy was called Bloot,’ said Katherine’s mother as the photo went from hand to hand, ‘although God knows why. It went all floppy like that after she was sick on it and we had to run it through the wash. There wasn’t a thing that girl owned that she wasn’t at some point sick on. Honestly, the constitution of a delicate bird.’

‘Such a shame she couldn’t be here today,’ someone said.

‘Oh, I know,’ said Katherine’s mother. ‘But she doesn’t have a moment to herself these days. She just works and works. And what with all this terrible cow business …’

Heads nodded in agreement, and although Katherine couldn’t be sure, and would later convince herself she’d imagined it, she thought for a moment that more than one pair of eyes flicked her way in the reflex judgement typical of any family gathering: attendance was closely related to employment. People were grateful if you came, but then also assumed that your job was neither important nor demanding, since all the relatives with important and demanding jobs were much too busy to attend more than once a year, at which time they were greeted like knights returning from the crusades and actively encouraged to leave throughout the day lest anything unduly interfere with their work. Katherine’s sister had revelled in this role for several years now, and it irked Katherine that the less Hazel showed up, the more saintly and over-worked she became in everyone’s minds, while the more Katherine put in appearances and made an effort to be attentive to the family, the more she was regarded as having wasted her life. It was, admittedly, slightly different on this occasion, given that half the roads were now closed on account of the cows. Everyone that had made it seemed grimly proud, as if they’d traversed a war zone. Katherine couldn’t have cared less about the cattle, but she was enjoying the momentary respect her attendance seemed to have inspired.

The second photo was not produced until the first had completed its circuit. It was of Katherine’s father, dressed in a waxed jacket and posing awkwardly with a shotgun.

‘There’s Nick,’ said Katherine’s mother. ‘He didn’t hit a thing, of course, but he enjoyed playing the part. He had all the kit, needless to say, but that was Nick. Strong on planning, poor in execution. I took that picture myself.’

She paused pointedly before passing it round, encouraging a few nods of sympathy from the aunts and uncles. Katherine’s mother had, for as long as Katherine could remember, reliably played the sympathy card when discussing the man who had fathered her children, lingered a couple of years, and then decamped for Greece with a woman he’d met at the doctor’s surgery while waiting to have his cholesterol levels checked. Katherine received two cards a year from her father, for Christmas and her birthday, with a third bonus card if she achieved anything noteworthy. He’d called her just once, soppy-drunk and clearly in the grip of a debilitating mid-life crisis, and told her always to beware of growing up to be like either of her parents.

The photograph circled the table and was followed, with precision timing, by a colour snapshot of Homer, the family dog, who, never the most intelligent of animals, had leapt to his death chasing a tennis ball over a series of felled trees, impaling himself on a shattered branch and leaving Katherine, who had thrown the ball, to explain to her mother why her precious mongrel was not only dead but in fact still needed to be prised from his branch, while her daughter remained inexplicably unharmed and unforgivably dry-eyed.

The next and, as it turned out, final photograph, was of Daniel, Christmas hat tipsily askew, raising a glass from his regal position behind a large roast turkey.

‘Ahh,’ said Katherine’s mother. ‘There’s Daniel, look. Such a darling. Did you ever meet Daniel? Oh, of course, he came to that thing a few years ago. Such a charmer. I just adored him. Poor Katherine. He’s the one that got away, isn’t he, dear?’

‘Not really,’ said Katherine. ‘No.’

‘Still a rough subject,’ said Katherine’s mother, smiling at Katherine in a maternal fashion – something she only ever did in public. ‘Daniel’s doing ever so well these days, of course, unlike some, who shall remain nameless.’ Her gaze, morphing like the liquid figures of a digital clock, became sterner. ‘So easy to get stuck, isn’t it?’

She slid the last picture back into the folds of her purse, snapped the clasp, and returned the purse to her handbag, leaving everyone to look once, briefly, at Katherine, and then gaze uncomfortably at the tabletop, silent until the welcome arrival of coffee, at which point Katherine politely excused herself in order to go to the bathroom and tear a toilet roll in half.

Katherine didn’t like to think of herself as sad. It had a defeatist ring about it. It lacked the pizzazz of, say, rage or mania. But she had to admit that these days she was waking up sad a lot more often than she was waking up happy. What she didn’t admit, and what she would never admit, was that this had anything whatsoever to do with Daniel.

It wasn’t every morning, the sadness, although it was, it had to be said, more mornings than would have been ideal. Weekends were worst; workdays varied. The weather was largely inconsequential.

Time in front of the mirror didn’t help. She got ready in a rush, then adjusted incrementally later. She hadn’t been eating well. Things were happening to her skin that she didn’t like. Her gums bled onto the toothbrush. It struck her that she was becoming ugly at a grossly inopportune time. Breakfast was frequently skipped in favour of something unhealthy midway through her working morning. She couldn’t leave the house without a minimum of three cups of coffee inside her. Recently, she’d started smoking again. It helped cut the gloom. She felt generally breathless but coughed only on a particularly bad day. At some point during the course of her morning, any morning, she would have to schedule time for nausea.

For the past two years, Katherine, having moved from London to Norwich by mistake, had been the facilities manager at a local telecommunications company. Her job had nothing to do with telecommunications, but centred instead on the finer points of workplace management. She was paid, she liked to say, to be an obsessive compulsive. She monitored chairs for ongoing ergonomic acceptability and suitable height in relation to desks and workstations, which she checked in turn to ensure compliance with both company guidelines and national standards for safe and healthy working environments. She performed weekly fire alarm checks and logged the results. Each morning she inspected the building for general standards of hygiene, presentation and safety. She fired at least one cleaner per month. She was widely resented and almost constantly berated. People phoned or messaged at least every hour. Their chairs, their desks, the air conditioning, the coffee-maker, the water cooler, the fluorescent strip lighting – nothing was ever to their liking. The numerous changes Katherine was obliged to implement in order to keep step with current health and safety legislation made her the public advocate of widely bemoaned alterations. Smokers had to walk further from the building. Breaks had to be re-negotiated. Her job allowed no flexibility, meaning that she frequently came off as humourless and rigid. The better she was at her job, the more people hated her. By general consensus, Katherine was very good at her job.

Aside from the basic majority of colleagues who couldn’t stand her, there also existed a splinter group comprising the men who wanted to fuck her. Katherine thought of them as contested territory. Some of them wanted to fuck her because they liked her, and some of them wanted to fuck her because they hated her. This suited Katherine reasonably well. Sometimes she fucked men because she felt good about herself, and sometimes she fucked them because she hated herself. The trick was to find the right man for the moment, because fucking a man who hated you during a rare moment of quite liking yourself was counter-productive, and fucking a man who was sort of in love with you at the peak of your self-hatred was nauseating.

To date, Katherine had fucked three men in her office, one of whom, Keith, she was still fucking on a semi-regular basis. The other two, Brian and Mike, had faded ingloriously into the middle distance, lost amidst the M&S suits and male-pattern baldness. Brian had been first. She’d broken her no-office rule for Brian and, with hindsight, he hadn’t been anywhere near worth it. She’d broken her married-man rule too, and the rule about men with kids. She resented this because it seemed, in her mind and, she imagined, in the minds of others, to afford Brian a sense of history he in no way deserved. The reality was, at the time Katherine had made a conscious and not entirely irrational decision to jettison so many of the rules by which she had up to that point lived her life, Brian had happened to be in the immediate vicinity, and had happened, moreover, to be a living exemplar of several of those rules. Hence the sex, which took place quite suddenly one Tuesday afternoon after he drove her home, continued through to the following month, and then ended when Katherine began wondering if some of her rules had in actual fact been pretty sensible. Brian was fifty-something (another rule, now that she thought about it), fat, and in the midst of an epic crisis. He drove a yellow Jaguar and had a son called Chicane. They never finished with each other or anything so tiresome. Katherine simply ceased to acknowledge his existence and the message was quietly, perhaps even gratefully, received.

Mike was, on the outside at least, different. He was Katherine’s age (thirty, although there was room for adjustment depending on her mood), single, and surprisingly good in bed. Even more surprisingly, Katherine found him to be capable of several almost full-length conversations when the mood took him. Their affair (it wasn’t really an affair, but Katherine liked to define it as such because it added value to the experience and because she’d not long previously fucked Brian and was hoping, in a secret, never-to-be-admitted way, that she might be in a phase of having affairs, which would of course completely legitimise her sleeping with Mike) lasted almost two months. It ended when Mike found out that Katherine had slept with Brian. Much to Katherine’s irritation, Mike turned out to be in possession of what he proudly called a moral compass. Katherine was not impressed. As far as she was concerned, morals were what dense people clung to in lieu of a personality. She told Mike as much after he tried to annex the high ground over the whole adultery issue. He ignored her. He couldn’t respect her, he said. Katherine would always remember him walking away from the drinks cooler, shaking his head and muttering softly, Poor Chicane … poor, poor Chicane. She felt grimly vindicated. Mike didn’t have any morals. He just had a bruised male ego and an inability to express himself.

All this, of course, had been a while ago, and there had been other, non-office-based men floating around during the same time period. Nothing had gone well. Katherine had started waking up sad a lot more often. The thing with her skin had started. She’d gained weight, then lost it, then lost a little more. Sleep was becoming increasingly difficult. Once, during a stretch of annual leave she’d taken purely to use up her quota and which she’d spent wearing a cereal-caked dressing gown and staring slack-faced at Nazis on the History Channel, she’d swallowed a fistful of pills and curled up in bed waiting to die, only to wake up five hours later in a puddle of vomit, many of the pills still whole in the mess. She had words with herself. She got dressed the next day and did her makeup and went into the city and collided with Keith, who suggested coffee, then food, then violent, bruising sex in his garage, her stomach pressed against the hot, ticking metal of his car bonnet.

‘I remember once …’ said Keith, lying back against the car afterwards, Katherine beside him, both of them smoking and waiting for the pain to subside. ‘What was I … Fuck it, it’s gone.’

There were days when it all seemed sordid and doomed; days which, oddly, Katherine romanticised more than the days of hope. There was something doomed about Keith generally, she thought, and she liked it. He was forty-one (because, she thought, once you’d broken a rule, it was no longer really a rule, and so couldn’t be said to have been broken a second time); thin on top and thick round the middle. At work he wore crumpled linen and skinny ties. In the evenings he favoured faded black denims and battered Converse. He liked songs about blood and blackness: guitar-driven thrash-outs that made him screw up his face and clench his teeth like a man battling a bowel obstruction. He had pale, slightly waxy skin and grey eyes with a white ring around the iris. Katherine had read somewhere that this had medical implications but she couldn’t remember what they were and so chose not to mention it. She liked the idea that Keith was defective; that he might be dying. She liked the fact that he was open about what he called his heroin years. She even liked the way he hurt her in bed: the sprained shoulder, the deep gouge on her left thigh. Keith was different in what Katherine saw as complementary ways. He would never love her, would probably never love anyone or anything, and Katherine admired this about him. He seemed beyond the concerns that threatened daily (yes, daily by now) to swallow her whole. By definition, of course, this also placed him beyond her, but she liked that too.

She didn’t live in London. There were mornings when she had to stare forcefully into the mirror and repeat this to herself like a mantra. On a good morning she could just about say the name of her actual location, but it was hard. She and Daniel had moved here together, ostensibly for his job. There were unspoken implications regarding the pitter-patter of little feet. But announcements were not forthcoming, and then they broke up, and then London looked like it would be lonely, and now she was stuck.

Her mother rang with reliable frequency. Always a practical woman, Katherine’s mother felt the best way to voice her concerns about Katherine’s well-being was to be direct at all times. This seemed to involve repeatedly asking Katherine if she was OK, which of course had the effect of making Katherine feel a long way from OK.

‘Are you eating enough?’ her mother would say bluntly. ‘Are you eating healthy foods?’

‘Yes,’ Katherine would say, midway through a doughnut. ‘This morning I had porridge for breakfast, and for lunch I had a baked potato with tuna fish. For dinner I’m going to have grilled chicken breast.’

‘Are you being facetious? Because it’s unattractive you know. And not entirely mature.’

‘I’m being honest. Is that mature?’

‘That depends entirely,’ said her mother, ‘on what you’re being honest about.’

She met with Keith only on selected evenings. They fucked and drank and rarely spoke, which suited Katherine. He bought her a vibrator as a present: gift-wrapped, with a heart-shaped tag that read ‘Think of me’. She donated it, tag and all, to her local charity shop on her way to work, buried at the bottom of a carrier bag filled with musty paperbacks and a selection of Daniel’s shirts she’d found amidst her archived clothes. She never saw it for sale, and wondered often what had become of it. She liked to think one of the elderly volunteers had taken it home and subjected herself to an experience so revelatory as to border on the mystical.

‘Keith,’ she said one evening, deliberately loudly, in a crowded restaurant she’d selected precisely because she knew it would be crowded when she asked the question. ‘How many people are you fucking right now?’

‘Including you?’

‘Excluding me.’

‘Three,’ he said calmly. ‘You?’

‘Four,’ she lied.

‘Is it Daniel?’ her mother asked during one of her interminable phone calls. ‘Because I understand, you know, I really do.’

‘It’s not Daniel, Mother.’

‘He sent me a birthday card last week. He always sends me Christmas and birthday cards. Isn’t that nice?’

‘It’s not nice,’ said Katherine. ‘It’s anally retentive. He sends you cards because you’re on his list. It’s basically an automated response. It never occurs to him to change anything.’

‘Does he send you cards?’

‘No.’

She hated the idea that she might be the sort of person who had mummy issues. She was, or so she liked to think, much too alternative and free a person to find herself constrained by an unimaginative inability to slough off all those childhood hurts. That said, she wasn’t entirely above the occasional girlish fantasy of dying and yet somehow still being able to watch her own funeral, where her mother would, she hoped, hurl herself, weeping like a Mafia wife, onto her coffin. As a child, Katherine had almost always imagined her death to be the result of suicide. Now, older as she was, and so much more aware of the utter lack of romanticism in killing herself, she imagined instead that some tragic external event would be responsible for her passing; something sudden and only just within the realm of possibility, such as being struck by lightning or pancaked by tumbling furniture.

One could, Katherine was aware, come to all sorts of dim GCSE-level psychological conclusions about her mother, her father etc. etc. Needless to say, Katherine drew none of these conclusions for herself and was so resistant to their application that few people tried to draw them for her. Daniel, of course, being Daniel, had been one of those few, and it had caused such an almighty argument, which snowballed from an exchange of words into an exchange of crockery, that he had never dared go near the subject again unless, as was sometimes the case, he quite consciously wished to start an argument. He had once, in a display so petulant and pathetic that Katherine had merely stood aside and laughed, flounced around the lounge in what he clearly thought was an excellent impression of Katherine – all pouty lips and flappy hands – saying in a put-on baby voice that forever afterwards severely limited his sexual appeal in Katherine’s eyes, My mummy doesn’t love me. This was, of course, towards the end of their relationship, and while not exactly a contributing factor in the split, certainly didn’t work in his favour.

The truth, if there was such a thing, was that Katherine rather admired her mother. Daniel, clearly proud of himself at coming up with the metaphor, had likened this to Stockholm Syndrome. There was, Katherine would be the first to admit, an atomic element of truth in this, but it was also, or so she maintained, a rather gross misunderstanding of the sort of relationship she and her mother had enjoyed (yes, enjoyed) over three decades of mud-slinging, belittling, mocking and general one-upmanship. Katherine’s mother was, plainly, so utterly dysfunctional that it was a wonder she even managed to wash her armpits and find something to eat of a morning. But far from concealing this, or feeling any sense of shame about it, she advertised it, as if it were the very thing that set her apart from everyone else. Which, of course, it was. Katherine had seen her mother in almost every degrading situation in which it was possible for a mother to find herself in the presence of her daughter: drunk on Pernod at ungodly hours of the day; sprawled naked in Katherine’s bed having inexplicably led her latest conquest there instead of to the master bedroom; dumped in public by Julio, her swarthy squeeze of indeterminate Mediterranean origin. It was so predictable as to be banal. But oddly, Katherine felt rather proud to have come from such stock, and the whole picture reassured her that having children didn’t have to be the end of unpredictability. After all, she and her sister had both turned out reasonably OK, and her mother had maintained a verve and sense of daring usually reserved for women with zero in the way of offspring. It seemed, Katherine thought, a reasonable compromise. Indeed, she had to think this; there was no other choice. Opinionated as Katherine was, and as quick as she might have been to charge into the realm of near-total judgement and dismissal of others who failed to meet her own, admittedly rather warped sense of the world, she was not a hypocrite, and would not allow herself, no matter what her inward feelings of predictable pain might be, to castigate her mother for enjoying a lifestyle and attitude Katherine herself aspired to. Whatever effect her mother’s waywardness had had on Katherine, Katherine still had to judge her not as her mother, but as a woman, and this was convenient in that it simultaneously reinforced Katherine’s beliefs about all manner of subjects (motherhood, womanhood, men, relationships, and so on and so on) but also allowed her to completely ignore so many other issues which would, if she actually thought about them, cause not only inconvenience but probably also considerable pain.

The problem, though, was Daniel, and all the things that changed with his arrival. Katherine had managed, through stubbornness and evasiveness and distraction, to stave off introducing him to her mother for almost a year, and when she did, her worst fears were realised. Katherine’s mother, for all her flippant pronouncements about men and the ever-growing list of things for which they were no good, actually approved of Daniel in a way she hadn’t even hinted at when Katherine had introduced her to previous boyfriends. After a suitably dull dinner, during which all concerned did their best not to stray from the middle of the conversational road, Katherine had seen Daniel out to his car and returned to find her mother smiling happily, her glass of wine unexpectedly untouched beside her, her cigarette not even lit, filled with nothing but praise for the man whom Katherine had been so convinced she would hate. Not that there was, on the surface, much to hate about Daniel. He was personable and polite and oddly charming in a quiet, slightly under-confident way. It was just that Katherine had assumed, given the weight of previous evidence, that her mother would by her nature disapprove of anyone so sensible, so reliable, so (or so she’d thought at the time) normal. And from the moment Katherine’s mother pronounced Daniel the best thing ever to have happened to Katherine, everything that had felt so certain seemed to fall apart in Katherine’s hands, and there was already, so early on, a creeping sense that she and Daniel were doomed and, as a result, so were she and her mother. Because as she listened to her mother talk that evening – sober and calm and sensible in a way Katherine was sure she had never been before – Katherine realised that the things she admired about her mother were not, as her mother was so adept at convincing those around her, things her mother admired about herself. Her individualism, her rugged isolation, her mistreatment of the men in her life, were only, it seemed, worn as badges of honour because it was better than wearing them as the things they really were: flaws, injuries, failings. The telling remark was when she told Katherine that this was what she’d always wanted for her – a good man, a stable relationship, a happy home life. In that instant, Katherine could feel it all evaporating, rising ceiling-ward with the smoke from her mother’s cigarette, which she had waited for the duration of the conversation to light.

During the evenings she wasn’t with Keith, which were numerous given that Keith had three other fucks to squeeze into his week, Katherine read and watched the news. She rarely watched anything else on television. Like much of Katherine’s life, what she read and what she watched were governed by her sense of types of people: types she wanted to be versus types she couldn’t stand. She didn’t want to be the sort of woman who watched soaps and weepie movies. She wanted to be the sort of woman who watched the news and read the Booker list. She imagined herself at parties, despite the fact she never went to parties, being asked her opinion on world affairs and modern literature.

Confronted with such topical discussions, however, she found herself adrift and exposed. It wasn’t that she didn’t know what was happening, or that she didn’t, in some distant and largely hypothetical way, care: it was simply that she felt unable to muster appropriate levels of distress. Once this fact became clear, it seemed to spread its tentacles into the rest of her life in such a way as to make her question, not for the first time, exactly how human she could lay claim to being. Watching the news was, essentially, watching life, and the manner of her watching unnerved her. She thought of it as a certain lack of connection, a phrase, coincidentally, that she often used about men with whom she hadn’t gotten along. Others saw it as coldness, a phrase men Katherine hadn’t gotten along with often used to describe her. Unmoved was a word that came up a lot, both in Katherine’s head and in other people’s descriptions of her. Emotionally hard-to-impress, was the way she preferred to think about it. Just as declarations of love were not enough to stir the same in her, so footage of, say, starving Haitians was not enough, in and of itself, to cause the kind of damp-eyed distress that seemed so automatic in others. Swollen, malnourished bellies; kids with flies in their eyes; mothers cooking biscuits made of earth. It was faintly revolting. Sometimes, when in a particularly quarrelsome mood, Katherine asked people exactly what the relevance was. For some reason, people tended to find this question offensive. They cited vague humanitarian criteria. The word children came up a lot, as if simply saying it explained everything.

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.