Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

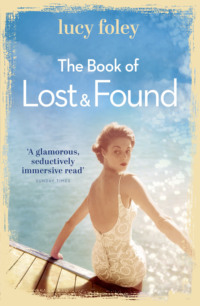

Kitabı oku: «The Book of Lost and Found: Sweeping, captivating, perfect summer reading», sayfa 4

The Tale of Evelyn Darling

Evelyn Darling was born into the sort of life in which most things could be guaranteed. Her father, Bertram, had inherited his father’s metallurgical business, and had seen business boom during the First World War. As his only child, Evelyn stood assured of a large inheritance and a cosseted future. However it soon became clear that she wasn’t to be satisfied by the sort of life that heiresses normally lead. She had more ambitious and unusual plans for her future.

As a girl, Evelyn had gone several times to the ballet with her parents, and she had never seen anything as beautiful, as magical, as the creatures that flitted back and forth before her on the stage. It became her wish to learn to dance like them, and her father, unable to refuse her in anything, paid for her to have lessons – as many lessons as she could endure. He wasn’t sure about letting her perform: it didn’t seem to be quite the thing for girls of the sort of class to which he aspired. Eventually, though, he permitted her to dance in a small way at private gatherings.

Evelyn became rather good. Not, perhaps, of the highest calibre, but talented enough by nineteen to catch the eye of one young gentleman in particular. She might not have been conventionally pretty, Evelyn, but she had a way of moving – like a wood nymph – and a voice like the high clear ringing of a bell.

In 1935 Evelyn and Harry were engaged to be married. Evelyn would take up dancing again after they wed, but she would probably never perform again: it wasn’t fitting for a married woman to do so, and, besides, Harry was the love of her life now.

A scant couple of months before the date that had been set for the ceremony, Harry took Evelyn for a drive in the Sussex countryside in the new car that Bertram had bought them as an early wedding present. It was a glorious day, full of the promise of summer, the air filled with sunlight, the roads dry, so no one could be quite sure what it was that caused the tyres to skid. What could be established, however, was that the car was travelling at great speed, far too fast for Harry to have righted their course before they ploughed into one of the beech trees that lined the roadside. Evie was lucky. She lost the baby that she had not even known that she had been carrying, and her right leg was fractured in seven places, forever after to be held together by an ingenious framework of metal pins and bands. Harry was not so fortunate: he was killed outright.

Evelyn, for all the overabundance of her youth, was possessed of an innate toughness of character. She knew that she would never dance again, professionally or otherwise, that she would never again bear children, and that she could probably never love another man in the way she had Harry. And yet she took to the rehabilitation programme devised for her with great determination. Every day she would make the journey to Battersea Park – just across the bridge from her father’s townhouse – to perform her strengthening exercises in the green surrounds. It was here that she saw the troupe of orphanage girls in their maroon smocks taking their walk, with two of the sisters at helm and aft. In that moment the idea was born.

I don’t think it would be untrue to say that in my mother Evie found the daughter that she had never been able to bear, along with, perhaps, the story of success that could never have been hers. She taught her everything she knew. A year after Mum first crossed the threshold of the ballet studio, Evie had adopted her as her own.

In 1938, my eight-year-old mother won a scholarship to the Sadler’s Wells Ballet School and Company. The rest, as they say, is history. The orphanage, the hand-me-down costume that she’d first worn to train in – these became part of my mother’s fairy tale.

Fairy tales, however, do not always end happily – in fact, quite often it’s the opposite, despite what modern retellings may ask you to believe. That was a difficult lesson to learn; perhaps I am learning it still. The fourteenth of April 1985. I tried to think, later, of what I was doing at the time, the exact time when the crash happened. Did I know, at that moment, in some fundamental part of my being? I have a terrible suspicion that I was buying a round for some of my old art-school friends at the Goodge Street pub we met in: blithely going about my day with no idea of how my life had suddenly changed.

After the plane crash I moved back into the house in Battersea where the three of us had lived: a big, cluttered Victorian conversion on one of those streets leading away from the park. It was only me there now. A couple of years before, Evie had gone into a home, diagnosed with progressive dementia. For a long time, Mum had refused to consider the possibility of moving her into care. Her work as a choreographer had seen her travelling frequently, but she said that she would downsize and find work closer to home so she could spend more time looking after Evie. Yet Evie’s behaviour became increasingly confused and erratic. When she was found on the other side of the borough with a broken elbow and no knowledge of how she’d got so far from home, it became clear that she didn’t simply need more extensive care, she needed it round-the-clock. Mum couldn’t afford to stop working completely, and I had to be at the Slade, where I was taking my degree in Fine Art.

‘It would be better’, said the social worker at St George’s, who had an illustrated-textbook turn of phrase, ‘for her to have the company of others – which can be achieved with at-home visits, but is far more easily accomplished in a nursing home, where she can have a social life, too.’

I can see why my mother found the decision such a difficult one to make. This was the woman who had cared for her from infancy, without whose love and influence she would never have had the life she did. I know she suffered over it, felt that she was committing a terrible form of betrayal. There was the added complication that Evie didn’t always seem in a particularly bad way – she could have moments of sudden and startling lucidity, and there were whole days when it would appear that nothing at all was amiss. But the bad days were very bad, and the possibilities of what could happen in the hours Evie might be alone were frightening. In the end, Mum had accepted that there was no alternative.