Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

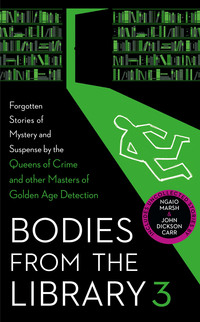

Kitabı oku: «Bodies from the Library 3»

BODIES FROM THE LIBRARY

3

Forgotten stories of mystery and suspense by the Queens of Crime and other Masters of the Golden Age

Selected and introduced by

Tony Medawar

Copyright

COLLINS CRIME CLUB

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

Published by Collins Crime Club 2020

Selection, introduction and notes © Tony Medawar 2020

For copyright acknowledgements, see Acknowledgements

Cover design by Holly Macdonald © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2020

Cover illustrations © Shutterstock.com

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008380939

Ebook Edition © July 2020 ISBN: 9780008380946

Version: 2020-05-28

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Introduction

SOME LITTLE THINGS

Lynn Brock

HOT STEEL

Anthony Berkeley

THE MURDER AT WARBECK HALL

Cyril Hare

THE HOUSE OF THE POPLARS

Dorothy L. Sayers

THE HAMPSTEAD MURDER

Christopher Bush

THE SCARECROW MURDERS

Joseph Commings

THE INCIDENT OF THE DOG’S BALL

Agatha Christie

THE CASE OF THE UNLUCKY AIRMAN

Christopher St John Sprigg

THE RIDDLE OF THE BLACK SPADE

Stuart Palmer

A TORCH AT THE WINDOW

Josephine Bell

GRAND GUIGNOL

John Dickson Carr

A KNOTTY PROBLEM

Ngaio Marsh

THE ORANGE PLOT MYSTERIES:

THE ORANGE KID

Peter Cheyney

AND THE ANSWER WAS …

Ethel Lina White

HE STOOPED TO LIVE

David Hume

MR PRENDERGAST AND THE ORANGE

Nicholas Blake

THE YELLOW SPHERE

John Rhode

THE ‘EAT MORE FRUIT’ MURDER

William A. R. Collins

Footnotes

Acknowledgements

Also Available

About the Publisher

INTRODUCTION

‘You and I, serene in our armchairs as we read a new detective story, can continue blissfully in the old game, the great game, the grandest game in the world.’

John Dickson Carr

One of the many joys of visiting the British Library and other repositories is coming across forgotten or unknown works by some of the most highly regarded writers of the Golden Age of crime and detective fiction, a period that can be considered to have begun in 1913 with Trent’s Last Case by E. C. Bentley, and to have ended in 1937, the year in which Dorothy L. Sayers sent Lord Peter Wimsey on a Busman’s Honeymoon.

This, the third collection of Bodies from the Library, continues our mission to bring into the light some of these little-known short stories and scripts, as well as works that have only appeared in rare volumes and never previously been reprinted. For this edition, there is a previously unpublished mystery featuring Ngaio Marsh’s famous detective, Inspector Roderick Alleyn, as well as a long lost novella in which John Dickson Carr’s satanic sleuth Henri Bencolin goes head to head with a brutal murderer. Stuart Palmer’s Hildegarde Withers confronts ‘The Riddle of the Black Spade’, and six authors go in search of a character as they rise to the challenge of building a short story around the same two-line plot. Among the more famous detectives featured are Anthony Berkeley’s Roger Sheringham, who does his bit to help defeat Hitler, and Senator Brooks U. Banner investigates a murderous scarecrow in a case from the pen of Joseph Commings.

And, in the year that marks 100 years of Agatha Christie stories, the inimitable Hercule Poirot investigates a murder foretold …

Tony Medawar

March 2020

These stories were mostly written in the first half of the twentieth century and characters sometimes use offensive language or otherwise are described or behave in ways that reflect the prejudices and insensitivities of the period.—T.M.

SOME LITTLE THINGS

Lynn Brock

Inspector Clutsam of the Yard came into the office of the senior partner of Messrs Gore and Tolley on the morning of Thursday, June 27, looking peeved. He came because Chief Inspector Ruddell of the Yard had called to see Colonel Gore at three o’clock on the afternoon of the preceding Monday and had not been heard of since.

‘Afternoon, Clutsam,’ said Gore, brightly. ‘Hot, isn’t it? You’d find it cooler without that natty little bowler, wouldn’t you?’

‘Now look here,’ growled the visitor. ‘What did Ruddell come to see you about? The Isaacson necklace, wasn’t it?’

‘Yes.’

‘Did he say anything to indicate any line of action he had in view concerning it?’

‘Not definitely. I gathered that he wanted us to drop the case. He conveyed to me that he had some information which made us quite superfluous. However, as he had by then spent half an hour trying to pump me for information, I concluded that he was talking through his hat.’

‘What time did he leave you?’

‘A little before four.’

‘Say where he was going next?’

‘I gathered somewhere where there was beer. Monday afternoon was also very hot, you remember, and unfortunately I could only offer him whisky. Which reminds me—’

Inspector Clutsam undid his face partially and accepted a cigarette and a whisky without prejudice. ‘In that case, Colonel,’ he said, ‘you’re the last person we know of who saw Ruddell alive.’

‘That,’ replied Gore, ‘is a very real consolation to me for his loss.’

‘S’nothing to be funny about,’ snapped Clutsam.

‘In life,’ murmured Gore, agreeably, ‘Chief Inspector Ruddell was not an amusing person. In death, I admit, he will be a very serious proposition for any sort of Hereafter to tackle. You think he is—er—deceased?’

‘Think? Ruddell’s been put away—I know it. There are plenty who’d do the job and glad of it. He’s been bumped off—I tell you I know it. He was due back at the Yard on Tuesday morning for a conference with the Commissioner. He didn’t stay away from that just to be funny. And we haven’t been able to find him for two days. Someone’s got him.’

‘As we are on the fourth floor,’ said Gore, reassuringly, ‘we have no cellar. But you are at liberty to inspect our strongroom—’

‘Why did you ask him to come here if you had nothing to tell him?’

‘We didn’t.’

‘He told the clerk you did—that you rang him up at two o’clock on Monday and told him you had something special for him about the Isaacson necklace.’

Gore considered his cigarette thoughtfully. ‘Now, there’s an instance of the importance of little things, Clutsam. If Ruddell had mentioned to me that he had got that message, I rather think both you and he would have been saved some trouble. But he didn’t. He just blew in as if he owned my office, talked eyewash for half an hour, lost his temper, and made an unsuccessful attempt to bluff us off the case. Pity; but, as it happens, it makes things more interesting.’

‘What things?’ snarled Clutsam.

‘Oh—stolen necklaces and things. As a rule, they bore us horribly—necklaces do. As a matter of fact, in strictest confidence, we decided just twenty-five minutes ago to leave Lady Isaacson to you gentlemen at the Yard. I’m wondering now if we shall.’

‘Stop wondering,’ growled the visitor. ‘You take it from me, Colonel, this Isaacson woman is a—’

‘Now, that’s just what Ruddell said about her,’ smiled Gore, winningly. ‘Have another little drink, and tell me why you people dislike this poor little lady so much. By the way, I hope you haven’t been very unkind to her about that smash-up on the Portsmouth Road last month, have you?’

Lady Isaacson was the wife of a millionaire and a very showily-handsome young woman. She had been comparatively unknown to fame until, some six weeks previously, she had made a determined attempt to kill one of His Majesty’s Ministers. Returning in the small hours of the morning from London to her Surrey residence near Farnham, she had crashed into a car going Londonwards, near Guildford. The Important Personage had escaped without injury, though his car had been badly damaged. But the incident had been given elaborate publicity by a certain section of the press, owing to the fact that the lady had been driving well over on the wrong side of the road at a furious pace, and, it was alleged, in a condition of intoxication. She had refused to disclose the name of a gentleman—not her husband—who had been her passenger at the time of the accident and on whose lap, according to the Important Person’s chauffeur, she had been sitting; a detail which had added additional piquancy to the fact that she had been returning from a very notorious night-club. The loss, a few weeks later, of an immensely valuable diamond necklace, which had been stolen from her town residence in Grosvenor Square, had revived the interest of the British public in this sprightly young person. The necklace had been insured for £120,000; but Lady Isaacson had issued a statement to the press disclaiming all intention to hold the insurance company concerned to its liability. She desired, she said, to discover if the police, who spent so much time in attending to other people’s business, could attend to their own with any satisfaction to the public.

Inspector Clutsam had shut up his face again. It was quite clear that he did not intend to answer the last question. Upon consideration of the face Gore picked up an unsigned letter from a little heap upon his desk, tore it across and dropped it into the waste-paper basket.

‘These little things—’ he said. ‘Now, you know you and Ruddell have been bullying Lady Isaacson to get out of her the name of that man who was with her.’

Clutsam made a noise of contempt as he rose.

‘Why did you decide to take Ruddell’s advice?’ he demanded.

‘We didn’t.’

‘Then why did you decide to drop the necklace affair?’

Gore reached for the Morning Post which lay on the top of his desk, and indicated a small paragraph tucked away at the foot of an unimportant page. ‘Another little thing, Inspector. Let’s see what you make of it.’

‘A curious occurrence,’ Clutsam read, ‘is reported from Bath. William Brandy, an elderly tramp, was admitted to the Infirmary on Tuesday suffering from injuries to his head and eye. According to his statement, he was struck by a heavy object while asleep during the previous night on his way from Salisbury to Westbury and rendered unconscious. On awakening in the morning he found close to him a wash-leather bag containing a necklace of what he supposed to be diamonds, fastened by a gold clasp set with three emeralds. Upon examination, however, by a Bath firm of jewellers, the supposed precious stones proved imitations. No explanation is forthcoming of the circumstances which occurred shortly after midnight in a remote spot at a considerable distance from any road or habitation. It is feared that the unfortunate man will lose the sight of the injured eye.’

‘Curious little story, isn’t it?’ Gore commented. ‘You remember that Lady Isaacson’s necklace had a clasp with three emeralds. Not that I suggest for a moment that hers is a fake … But that’s why we thought of dropping the case—’

‘It seems a damn silly reason to me’, blew Clutsam. He dropped the newspaper disdainfully. ‘Hell—I’m fed up. I’ve heard enough fairy tales in the last twenty-five years. I tell you what it is, Colonel. I’m sick of this job. Here I am running round like a potty rabbit for the last forty-eight hours, without a square meal or half-an-hour’s sleep, with everyone yelling at me, “Have you got Ruddell? Why the what’s-it haven’t you? You get him or you get out. There’s a man waiting for your job.” And these beggars in the papers blackguarding you. People looking at you as if you were a mad dog. Hell, I’m tired of it. Here, can I use your ’phone for a moment? My kid’s bad—diphtheria. I haven’t been able to get home since Monday morning.’

The burly, dogged figure bent over the instrument and rang up a Balham number. ‘That you, Alice? How’s the boy? Worse. Yes—get another doctor at once. No, I can’t go—I can’t, old thing … Sorry, girlie … Get the second opinion at once—the best man … I’ll ring up this evening … Stick it, kid …’

Clutsam straightened himself. ‘The kid’s got to go, the Missus says,’ he said, simply. ‘Bit of good news for a chap, isn’t it? Well, good morning, Colonel.’

A little thing—but it moved Gore. On the whole, his relations with the police, professionally, were rather trying. But no one knew better than he how hard was the task to which Clutsam and his colleagues, in uniform and out of it, were bound day and night—the ceaseless vigilance that alone made life for the citizen even tolerably secure. At the moment the man in the street and the man on the bench had their knives into the police. No doubt, in private life, Clutsam and his Alice had to suffer the averted eyes and sotto-voces of their neighbours.

Experience had taught Gore, too, what sort of a job it was to look for a lost man in London—long days, perhaps long weeks of false scents and monotonous failure—the search for a needle in a haystack of stupidity, falsehood and hostility. Also he was interested by William Blandy’s misadventure.

He took Clutsam by the shoulders and pushed him down into a chair. ‘Don’t be in a hurry,’ he said. ‘That telephone message we didn’t send has given me an idea. The cigarettes are there. It’s only an idea—but there is the fact that the lift was not working on Monday afternoon, and that Ruddell went down by the stairs. Sit tight for a bit, will you?’

The bit lengthened to nearly half an hour before he returned; but he returned with news which brought the impatient Clutsam to his feet in a hurry.

‘I think I’ve found where Ruddell went when he left here,’ he said. ‘Care to see?’

The building in Norfolk Street, which housed Messrs Gore and Tolley on its fourth floor, contained the offices of some score of assorted businesses. On the third floor, by the staircase down which Gore led Clutsam, were, at one end of a long corridor, the offices of a literary agent, at the other end those of a turf accountant named Welder, and, facing them, those of the ‘Victory’ Aeroplane Company. In the doorway of Mr Welder’s offices the caretaker of the building awaited them, jangling his bunch of keys. They went in and surveyed the three meagrely-furnished rooms. Gore pointed to a window which he had opened.

‘I rather think they got him in here somehow. And I rather think they got him out of here by that window, when they were ready—probably at night, when it was quiet.’ He leaned out to point down into a narrow yard below. ‘Some of the tenants here park their cars down there. There’s a gate into the street. It would be quite simple to cart him away …’

Clutsam stared about him incredulously. ‘Bunkum,’ he snapped. ‘There isn’t a chair out of place. Ruddell would have wrecked this place before six men got him. There isn’t anything to show—’

Gore pointed to a cigarette which lay under the table of the inner office. ‘Just one little thing, Clutsam. Look at it. Been in trouble, hasn’t it?’

Clutsam stooped and picked up the cigarette, which was badly bent and burst at its middle. But he derived no other information from it.

‘You smoked one of that brand just now, Clutsam,’ Gore smiled. ‘If you’ll forgive swank, it’s rather an expensive brand. Also you notice that it has barely been smoked. Now, I gave Ruddell a cigarette just as he was leaving me on Monday afternoon. Of course, they tidied up. But they left this little thing. Careless of them! Why wasn’t the lift working on Monday afternoon, Parker?’

The caretaker could not say. The lift had jammed at a little before three, but had been got right shortly after four. He had never seen Mr Welder, never known anyone to use these offices since they had been taken by Mr Welder a couple of weeks before. From the agents who had let the offices the telephone elicited no information except that Mr Welder had paid six months’ rent in advance. They had never seen him.

‘Let’s see,’ suggested Gore, ‘if the people over the way can tell us anything about him.’

But the clerk in charge of the ‘Victory’ Company’s offices—apparently the staff consisted of a clerk and the manager, Mr Thornton, who was away—had not seen anyone enter or leave Mr Welder’s offices.

‘Not on last Monday afternoon—about four?’

‘I wasn’t here on Monday, sir. The boss gave me a day off.’

‘Ah, yes,’ smiled Gore. ‘That must have been nice. Mr Thornton himself, I suppose, was here that afternoon?’

‘I believe so, sir.’

‘On Tuesday?’

‘No, sir. He went down to the works at Bath on Monday night. He’s down there now, sir.’

‘Ah, yes, yes, yes,’ said Gore, affably. ‘Many thanks.’

On the landing he looked at his watch. ‘Two more little things, Clutsam. And here’s a third. On the occasion of her first visit to us, Lady Isaacson was indiscreet enough to inform me that Mr Thornton had recommended her to consult us … Care for a run down the Bath road? I ought to be able to get you back to London by six.’

Inspector Clutsam was not a nervous man, but he was, for many reasons, glad when the big Bentley deposited him in Bath two and a half hours later. They failed to see Mr Thornton; he was ‘up’, it seemed, testing a bus. It was not known when he would come down.

But they saw Mr William Blandy—not at the Infirmary, which he had left that morning, but at a police station behind Milsom Street, where the arrival of the celebrated Inspector Clutsam created a feverish stir. Before they saw William Blandy, who had been brought in on a charge of drunkenness, they saw the necklace—a quite first-rate bit of fake.

‘No pains spared,’ Gore commented. ‘Sixty-four diamonds, three emeralds, and twelve small diamonds in a clasp of Egyptian design—’

Blandy was produced—a haggard, depressed old down-and-out, still stupid with beer, which had made him peevish. The pupil of one bloodshot eye was still distended with atropine; he had torn off the plaster from an ugly cut on his forehead, which was still oozing blood. His story was that on Monday morning he had set out from Salisbury for Westbury and Bath, that he had lost his way trying to make a short cut across the Plain, and had ultimately lain down to sleep somewhere or other—he had no clear idea where, save that next day he had walked for two hours before reaching Westbury. He had been sound asleep when he had been struck by a mysterious missile which had rendered him unconscious. When daylight had come he had awakened, still sick and dizzy, and had found the wash-leather bag lying beside him. There had been no road near the spot, no house in view—as he himself expressed it, ‘no blinking nuffin’.’ His eye had been very painful, and his forehead had bled a lot, but he had contrived to walk to Bath. He was very indignant over his arrest, which he denounced as part of the plan of the police to deprive him of his reward. Nothing could shake his belief that the necklace was the genuine thing.

‘Quite sure,’ Gore asked, ‘that that ugly big cut on your forehead was made by this thick, soft, wash-leather bag?’

‘Sure? Of course I’m sure.’

Gore turned to the station sergeant. ‘Found anything else on him, Sergeant?’

In deference to Inspector Clutsam, the sergeant apologised profusely. The man had only been brought in an hour before. He fell upon the unfortunate Blandy at once, and, to his considerable surprise, extracted from various parts of his dingy person the sum of nine pounds odd in notes and silver, together with an expensive fountain pen. Blandy refused to say how he had come by this wealth.

‘That’s a very smart boot you’ve got on your right foot, my man,’ said Gore. ‘Let’s have a look at it. Don’t be coy.’

The prisoner’s footwear made certainly the oddest of pairs. His left boot was a shapeless, split, down-at-heel old ruin, and presented the appearance of having been dipped in whitewash the day before. The right boot was a dapper, sharp-toed, even foppish, affair of excellent quality, still presenting, beneath its dust, evidences of recent polishing.

‘Now, it’s a curious thing, Clutsam,’ mused Gore, ‘but I recall distinctly that Ruddell was wearing an extremely doggy pair of boots on Monday afternoon. I wonder if by any chance—’

Clutsam had the boot off and examined it with bristling ruff. Then he fell upon the luckless Blandy with a ferocity which suddenly sobered that unlucky finder of windfalls. He admitted that he had found the boot, close to where he had found the bag—about a hundred yards away. He had also found the nine pounds odd and the fountain pen in a pocket wallet. He had thrown away the wallet and his old right boot. He was placed forthwith in Gore’s car, which, followed by another containing a posse of uniformed searchers and two plain-clothes men on motor-cycles, made a bee-line for the high escarpments which rise against the sky to the south of Westbury, climbed them by a vile cart-track, which ended at the top, and came to a pause with the vast, flatly-heaving expanse of Salisbury Plain stretching away miles and miles to blue, daunting horizons.

The task of finding Mr Blandy’s sleeping-place appeared, in face of that vast, bare expanse, rising and falling endlessly with the monotony of the sea, almost hopeless. The man had clearly the vaguest recollection of the route by which he had reached that point—the last point of which he was even tolerably certain. The cortège remained motionless, gazing dubiously at the dismaying scenery.

But fortunately another little thing presented itself for Gore’s attention.

‘That left boot of yours has been in wet chalk,’ he said. ‘There’s been no rain for a fortnight. How did you manage it?’

‘I got in some water, looking about,’ Blandy replied, surlily.

Gore stopped his engine.

‘He came along this track, he thinks, Clutsam. Well—there’s only one kind of water on Salisbury Plain. We’ve got to find a dew pond with an old boot and a wallet near it. If you multiply twenty by twenty-five you’ll get the size of Salisbury Plain in square miles. I’m afraid you won’t get back to town by six, Inspector.’

They placed Blandy upon the track—little more than a sheep-track—and urged him forward. For nearly two miles he drifted slowly southwards, followed by his escort. But track crossed track; he went down into long, twisting valleys, and toiled up over long, baffling slopes, and became visibly more and more doubtful. At length he halted, completely lost. They left him at that point in charge of a man, and spread out to look for dew ponds.

It was just seven o’clock when an excited motor-cyclist rounded up the part with the tidings that Blandy’s discarded boot had been found, as Gore had predicted, close to a large dew pond, about four miles south-east of the point at which they had debouched on to the Plain. Hurried concentration produced, after some time, some further finds—Chief Inspector Ruddell’s wallet, a bunch of keys, a small automatic pistol with an empty magazine, one of Messrs Collins’ pocket novels, and a silk handkerchief marked with the initials W.R.

At Gore’s suggestion these articles were left where they were found, spaced out at varying intervals over a distance of nearly a mile, and marked by sentinels. Blandy was moved up to point out the exact spot where he had slept, and indicated the gorse bush in which the automatic had been found. He admitted then that he had found it, but had been afraid to take it. He agreed that possibly it might have been the automatic which had struck him.

Gore looked along the line of sentinels. ‘Anything occur to you, Clutsam? I mean, from the fact that these things are all along one dead straight line—from this dew pond to where that farthest man is. Let’s just see where Bath lies from here.’

One of the motorcyclists produced a map; Gore himself produced a pocket compass. A very brief inspection revealed the fact that the line of sentinels ran dead for the point where, invisible and thirty miles away to north-west, Bath lay among its hills. ‘By Jing!’ muttered Clutsam.

Gore turned about to face south-east again. ‘Well, now,’ he smiled, ‘all we have to do is to go along our line until we come to Ruddell.’

The vast emptiness of the landscape chilled Clutsam’s hope.

‘Hell!’ he murmured.

‘Well,’ demanded Gore, ‘if you can find me in England a likelier place for a stunt of this sort, we’ll go there. Of course, Ruddell’s your bird, my dear fellow.’

‘Well, we’ll go on—for a bit,’ agreed Clutsam at last.

The party spread out and advanced in parallel, with occasional halts to verify the line of march. The sun went down in a final crash of gold and scarlet, the landscape greyed; a chill little wind whispered of the coming night. The men began to mutter. Were they going to walk to Salisbury? As the miles crept up, even Gore himself began to think of a dinner that wouldn’t happen.

But the end of the quest came with startling suddenness. Abruptly, from behind one of those rings of beeches that studded the desolation blackly, an aeroplane shot up, wheeled, and came rushing towards them. Twice it circled above their heads, then fled away to north-west, along the line by which they had come.

‘Well, we shan’t find Mr Thornton,’ commented Gore. ‘Perhaps not Ruddell. All the same, I should like to see if there’s anything in that clump of beeches.’

They pushed on for a last mile and passed into the gloomy shadow of the trees. In there was an abandoned farm, silent and desolate. But in its living room they found the remains of a recent picnic meant for four people. And in a padlocked cellar of extremely disagreeable dampness and darkness they found Chief Inspector Ruddell, handcuffed and flat on his back on the slimy floor to which he was securely pinned down. Above his head a water butt stood on trestles, and from its spigot, at intervals of thirty seconds or so, a drop fell upon his forehead. For the greater part of three days and two nights that drop had fallen in precisely the same spot—between the victim’s eyes. Ruddell was a man of iron nerve, but he was rambling a bit already.

Day was breaking when Gore deposited Inspector Clutsam outside his house at Balham. He waited until the big, burly man came hastening down the narrow little strip of garden again.

‘Good news, Colonel,’ he said. ‘The kid’s got through the night. They say he’ll pull through now. I won’t forget this. It’ll be a big thing for me.’

‘Good,’ smiled Gore. ‘But don’t forget the little things. You never know …’

Whatever it proved for Inspector Clutsam, the Yard maintained a modest silence concerning the affair. But Lady Isaacson was quite frank about it in a little chat which she had with Gore next day. In their anxiety to identify her male companion in the night of the smash (they suspected that he had been the driver of the car), Ruddell and Clutsam had undoubtedly overdone their repeated examinations of the lady, who had determined to ‘get some of her own back’. Thornton, a well-known flying man and, as Gore suspected, the hero of the ‘smash up’, arranged the plan and enlisted the necessary aides, three reckless airmen. An imitation necklace was procured and a vacant office opposite Thornton’s taken; a bogus robbery of the real necklace was actually carried out, leaving careful clues as bait for the police. The next step was to enlist Messrs Gore and Tolley as stool pigeons, and get Ruddell to their offices at a known hour. At three o’clock on the Monday afternoon the lift had been put out of action, Ruddell was in Gore’s office, and everything was ready.

As he went down the stairs, Ruddell had been met on the third floor by a young man who, under the pretence of having some information to give him, had persuaded him to enter ‘Welder’s’ offices. There, in an inner room, the fake necklace had been produced and had completely deceived the Chief Inspector. While he was examining it, Thornton and his fellow conspirators had entered the outer room. As Ruddell came out, they caught him neatly with a noosed rope, gagged him, and handcuffed him—not without a severe struggle, despite the odds—and, when the building was quiet, had lowered him in a sack to the Yard, and quite simply carted him off to Bath. There he had been transferred to a big passenger plane and carried off a little before midnight to the lonely old farm on Salisbury Plain which had been rented for the ‘stunt’.

The mysterious windfalls were simply accounted for. Above the Plain Thornton had had the pleasant idea of slinging the unfortunate Chief Inspector over the side of the plane by his waist and legs. In due course Ruddell’s pockets had emptied themselves of their heavier contents, while the rope holding one leg had slipped and had pulled off one of his boots.