Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

Kitabı oku: «Letters to the Earth»

Copyright

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2019

Original content copyright © Emma Thompson, Daniel Joyce, Tilly Lunken, Jenny Ngugi, Laline Paull, Ottilie Neser, Kayden Van Veldhoven, Sally Jane Hole, Jem Bendell, Niamh McCarthy, Simon Jay, Agnes Homer, Cate Chapman, Ella Crowley, Liz Darcy Jones, Simon McBurney, Ollie Barnes, Jackie Morris, Professor Stefan Rahmstorf, Tabitha Ravula, Stuart Capstick, Nicola Espitalier Noel, Jessica Taggart Rose, Elliotte Mitchell, Joanna Pocock, Daniela Torres Perez, Tyrone Huggins, Haydon Bushell, Rob Cowen, Christopher Nicholson, Isobel Bruning, Saibh Da Silva, Justin Roughley, Clare Crossman, Mary Benefiel, Jessica Siân, Lindsay Clarke, Veronika Schmidinger, Anna Hope, Blythe Pepino, Jo Baker, Katie Skiffington, Jay Griffiths, Ann Lowe, Polly Higgins, Claire Rousell, Nathan Bindoff, Emma Cameron, Alex Morrison Hoare, Tia Khodabocus, Tamara von Werthern, Bridget McKenzie, Harriet Hulme, Dr Rupert Read, Steve Waters, Molly Wingate, Bob Langton, Eva Geraghty, Kerala Irwin, Mark Rylance, Mairéad Godber, Renato Redentor Constantino, Nivya Stephen, Luke Jackson, Toni Spencer, Ashby Martin, Dr Gail Bradbrook, Hannah Palmer, Marian Greaves, Mike Prior, Minnie Rahman, Tamara Ashley, Casper Taylor, Professor Julia Steinberger, Luca Chantler, Caroline Lucas MP, Megan Murray-Pepper, Silvia Rodriguez, Lilli Hearsey, Trilby Rose, Eve Houston, Fiona Glen, Dulcie Deverell and Edi Rouse, Bishop Rosa dos Santos Bassotto, Farhana Yamin, Claire Rousell, Harkiran S. S. Dhingra

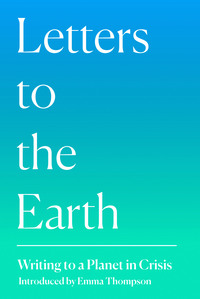

Cover design by Jack Smythe

Swallow illustration by Jakie Morris

The authors assert their moral right to be identified as the authors of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008374440

eBook Edition © November 2019 ISBN: 9780008374457

Version: 2020-01-02

Contents

1 Cover

2 Title Page

3 Copyright

4 Contents

5 Introduction

6 Dear Reader

7 In the Beginning

8 LOVE

9 Earth

10 In the Climbing Hydrangea of my Neighbour’s Fence

11 Dear Mr Walnut Tree

12 Milk

13 All the Trees

14 But the Greatest of These Is Love

15 Help Me Catch Our World

16 Letter to the Worms

17 Insects

18 I Love You, Earth

19 Now It Is Our Turn

20 Stories of You and I

21 Extinction Redemption

22 A Break Up Poem

23 We Don’t Shop at Waitrose

24 Be Kind

25 I Don’t Know Where I’ve Got This Balance Wrong

26 A Love Letter

27 Oh, Arrogant and Impudent Beloved Child

28 The Act of Naming

29 Everything

30 Everything Is Connected

31 LOSS

32 False Alarm

33 What Have We Done to the Planet?

34 Finding Dory

35 Cruise control

36 We Humans

37 The Act of Incremental Vanishing

38 Dear Animals

39 Nichollsia borealis

40 A Place I Call Home

41 Small Islands Everywhere

42 Why Should We Care?

43 Letter to a Starling

44 A Frog Shrivelled in the Dust

45 A Letter to the Dying

46 I Didn’t Even Know!

47 Amnesia

48 The Night Toby Denied Climate Change

49 The First Earth Day

50 A Letter to the Earth (If It Can Read?)

51 Sorry

52 On an Ancient Carving

53 Patient E

54 Fracture

55 Womb

56 For Aoife

57 Procrastination

58 Letter to an Endling

59 anything

60 EMERGENCE

61 Emergence

62 We Are in the Underworld

63 The Hospital

64 Trusting the Spiral

65 HOPE

66 A Scientist’s Dream

67 The Hawthorn Tree

68 Corrections

69 Thirteen

70 Active Hope

71 I’m Seeing Changes

72 Sleeping in the Forest

73 Hope in the Darkness

74 A Daring Invitation

75 An Apology/A Prayer

76 I Believe in You

77 2082

78 We Already Know the Answers

79 I’m Still So in Love with You

80 A Great Non-Conformity

81 A Nightingale Sang in Berkeley Square

82 Discontinuous Change

83 An Island Travelling South

84 ACTION

85 Ancestors

86 The Future

87 YOU

88 Galvanize

89 No One Is Exempt

90 A Massive Pink Vagina in the Middle of Oxford Circus

91 Put Your Head in the Sand

92 Use Your Voice

93 Correspondence

94 Dear White Climate Activists

95 From Broken to Breaking

96 Liveable

97 A New Civilisation

98 The Sixth Mass Extinction

99 A Failure of Imagination

100 Waymarkers

101 There Is No Excuse

102 Johnny from Sainsbury’s Checkout Begs

103 Last Generation

104 Enterprise

105 After the Rebellion

106 Turning

107 The Time Is Now

108 Samaúma

109 The Age of Restoration

110 What We Do Now Matters

111 Sea Change

112 The Time for Action is Now

113 Acknowledgements

114 Credits

115 About the Author

116 About the Publisher

LandmarksCoverFrontmatterStart of ContentBackmatter

List of Pagesvvi12356713141516192122232425262728293031323334353637383940414243444546474849505152535455565758596061626364656667697172737475767778798081828384858687888990919293949596979899100101102103104105106107108109110111112113114115116117118119120123125126127128129130131132133134135136137139141142143144145146147148149150151152153154155156157158159160161162163164165166167168169170171172173174175176177178181183184185186187188189190191192193194195196197198199200201202203204205206207208209210211212213214215216217218219220221222223224225226227228229230231232233234235236237241242243245249250251

Introduction

All humans know somewhere deep – somewhere like our spinal cords, somewhere we are not used to communicating with – that our planet is suffering. We know at a cellular level and it is causing us huge distress. It’s like being in a sci-fi story where we are under attack from the Martians – except in this story we are the Martians and there is no spaceship out there poised to save us from destruction. But let’s remember that because we are the authors of the story we can also be the authors of what comes next.

So many of our inventions – miraculous at the time – gas, coal, planes, cars, smoking (I loved it) are now the agents of destruction. It’s hard to let go of our addictions, so hard. But let go we must if we, and the greater web of life of which we are, after all, only a part, are to survive.

I wonder what the best way of helping us understand that is. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) reports, the terrifying documentaries, the relentless roll-call of climate disasters spread fearfully essential knowledge and are vital, of course. It goes without saying that we must educate ourselves and see for ourselves what is taking place. But something else needs to happen if our fear and rage and frustration are to succeed in transforming our world.

These writings have pulled me back into focus.

I can remember now how many bees I used to see in parks and gardens in London and on the hills of Argyll. I can remember the variety of butterflies, their miraculous beauty, strength and fragility. I realise how little I now see them and how heartbroken it makes me. I miss them in the visceral way I miss members of my family long since dead.

We all need to plug into our love for our home, our planet, our earth. The astronauts describe it so well – those people with fiercely trained scientific minds who may not necessarily open themselves to poetic imagination (that might be too dangerous). They suddenly see the vulnerable beauty of our pale blue dot in the reaches of dark space. They feel huge love and empathy for it and, crucially, they feel deeply protective.

Art – in all its forms – can turn us all into astronauts. It can help us out of the prison of assumption and the caverns of ignorance into the atmosphere of clarity and hope. The temptation to panic is very great but panic will always prevent useful action. I panic regularly about the planet and then I will often turn to small, everyday actions. One of them is to sit and contemplate the beauty of nature – to go to a park and read and look up every so often at the sky or at a tree and remind myself that while we are here, we can care for our home.

Or I can transform my panic by joining larger actions – like the XR protest at Oxford Circus which was so memorable and full of love. Standing on the pink boat reading Jackie Morris’s exquisite, anguished lament to the swallow was an extraordinary experience. I looked out over so many faces – some people, overwhelmed with grief, wept openly. The police came and stood around us but the atmosphere was peculiarly peaceful. Public moments of sharing – particularly the sharing of art – change the spaces and alter the atmosphere. This can give us vital strength. We must engage in these acts because – make no mistake – the ruling powers will not do enough to alter the course of this terrifying history. We are on our own and together we will have to make them.

My vision is sometimes blurred by the horror of the millions of deaths our fossil fuel habits have caused and by the certain knowledge that all of this will continue to get worse until it gets better – because so much of what we have done is irreversible.

But in the end, hopelessness serves no purpose. Fighting for everything climate change reversal represents, from the essential bee to global social justice, will never offer anything but active hope.

We must combine the determined and unstoppable organisation of our best instincts with the vision of astronauts.

The wave of change is here. The generation below mine is different. I feel it and I read it in these letters. They know we have failed them and instead of wasting time blaming us or even trying to punish us they simply act. The young do not mind change as much as the old.

They are our best hope and listening to them always makes me feel powerful once again. Plugging into that energy will recharge even the most tired of batteries.

Read this book and pass it on. Hand on your passion for the planet to the next person and never, ever give in. Convert your rage to action and your grief to love. I think the planet feels us as we do this. Perhaps it will even help us.

Emma

Dear Reader

In the early spring of this year a small group of women came together around a kitchen table to talk. We had been profoundly shaken by the increasingly dire news of climate and ecological collapse, and inspired by the work of Extinction Rebellion in bringing that news to the forefront of the public conversation. In our working lives we are theatre-makers and writers and we felt strongly that we wanted to find a way to facilitate a creative response to these times of emergency. For so long – too long – our professions had been eerily silent about this greatest of subjects. Why? Was this a failure of nerve? Of imagination?

We knew Extinction Rebellion were planning a huge, disruptive action in the streets of London in April, and we began to imagine a creative campaign that might sit alongside and speak to that Rebellion. As we talked and shared ideas, we sensed that this was a chance to hear from those who sit outside the usual theatrical and publishing circles, to take the pulse of the country in these times of growing anxiety and realisation.

From that initial conversation others were born; we met people, listened, and soon the idea of a Letter to the Earth emerged, a callout to the public to write a letter in response to climate and ecological emergency. The letter could be to or from the earth, to future or past generations, those who hold positions of power and influence, to other species. We also invited venues to come on board and host a reading of the letters, on a date in April, just before the International Rebellion was due to take place.

We created an email account and in February the callout went live. We waited, a little nervously. The inbox was quiet. Then one letter arrived, and another, then our first batch of schoolchildren’s letters, twenty or more young people responding to the call. The letters were moving, disturbing, vital.

The inbox kept filling: pictures drawn by seven-year-olds, letters from teenagers, nurses, great-grandparents. Letters were coming in from all around the world, from published poets, people who had never put pen to paper before. In reading through them, there were many occasions when one or other of us was caught short, moved to tears on public transport, or by the electric rise of the hairs on your arm when you know you are in the presence of something great, a truly remarkable piece of writing. This great unsayable thing, this anxiety, this fear, this love, was finding expression in so many voices. Their cumulative power was overwhelming.

And venue after venue was signing up: a Ukrainian Club in Huddersfield, a Conservative Club in Paddington, a pub in Kent, leading theatres up and down the country: the Royal Court, the National Theatre of Wales, Shakespeare’s Globe, and venues around the world, from Alabama to South Africa to Zambia.

By the time submissions closed we had almost a thousand letters in our keeping, an astonishing gift. We believe it to be the largest creative response to these times of crisis the world has yet seen.

On 12 April the letters were read at fifty-two venues worldwide. During the International Rebellion, in which Extinction Rebellion occupied five sites in central London for two weeks, the letters were read from every stage. From the truck in the centre of Marble Arch, from a single microphone in front of seated lines of people willingly putting themselves up for arrest on Waterloo Bridge, from the grass in the middle of Parliament Square, and, perhaps most memorably, from the top of Berta Cáceres, the now iconic pink boat, when youth strikers and performers came together on the XR ‘Day of Love’.

And now this collection: it has not been easy to choose from such a rich variety of voices, and the collection could easily have been twice as long, but the following selection feels both challenging and vital.

We have gathered the letters into five headings: Love, Loss, Emergence, Hope, Action. The headings are not prescriptive, though they may serve as a prescription: if you feel despair, turn to Hope; if you feel loss, you may find comfort in voices who feel as you do; or you may need to read poems that immerse you in love for this home we all share.

We encourage you, too, to read the book from start to finish, but if you do so you will see that this is not a simple journey from Love to Action: love also contains fear and anger, hope contains despair. This is not comfortable reading. It is not comfortable to read the words of teenagers who fear they will have no future, of children begging for change. Of adults horrified by the world they are complicit in creating. Of mothers who despair for their children. Of those stricken by grief at the daily, catastrophic loss of the living world they hold so dear.

Some of the boldest voices speaking to us through this collection are those from the Global South, in countries where ecological and climate catastrophe are a lived reality. Daniela Torres Perez challenges us not to turn a blind eye to the suffering of her home country Peru: ‘a place where the people with the least money are the ones that suffer most’. While Renato Redentor Constantino, writing from the Philippines, invites us to imagine ‘an island travelling south, a landscape on the move where compassion is the currency and solidarity the only debt people owe one another’. As climate breakdown arrives on the doorstep of those living in the north, it is important to remember this wider reality, one in which people of colour and people living in poverty have long been disproportionately affected by ecological breakdown.

There are no easy answers contained within these pages, no clear paths out of the maze in which we find ourselves, but there is courage here and there is hope, hope that – in the words of Joanna Macy – is active, that calls us to action. There is love that echoes and speaks back to loss. Voices that dare to imagine a more beautiful, equitable, generous way of being with ourselves, each other and all those who share this living, interdependent, planet that we call home.

With love, and hope,

Anna Hope, Jo McInnes, Kay Michael, Grace Pengelly

August 2019

In the Beginning

Dear Author of Genesis,

I know it’s pointless to begin like this, because you lived about three thousand years ago and are no longer around to answer my questions, but I think you would appreciate what I am trying to do in this letter, so I’ll carry on. You were a creative writer, an artist, and writers play around with words in ways that non-writers don’t always understand. It is the way you have been misunderstood that bothers me. In fact, not understanding you has brought the world you wrote about so lovingly to a moment of great danger, a danger I want to tell you about.

You started with these words: ‘In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth.’ And that’s how your book got its name, Genesis, Beginning. Then you went on to craft a great poem describing how God made everything in six days and rested on the seventh. That’s where the trouble started. I wish you had added a little note inviting your readers to take you seriously but not literally. In fact, I wish you had written a prologue on the art of reading. I wish you had reminded us that you were an artist responding imaginatively to the wonder of the universe, not a reporter taking notes on something happening in real time. But that’s how some people started to read you. Not as a glorious fiction that prompted their wonder, but as an accurate news report of a tumultuous week about six thousand years ago. You won’t believe this, but there are people alive in my time who insist on reading you that way. We could dismiss them all as endearing eccentrics, if it weren’t for something else they get wrong, something they again take literally – and this time it’s had consequences, very serious consequences.

On the sixth or last ‘day’ of your narrative, God creates all the living creatures on earth, the grand climax being the emergence of humanity, God’s special favourite.

‘So God created man in his own image, in the image of God he created him; male and female he created them.’

Then come the fateful instructions to these human beings about how they are supposed to live:

‘And God blessed them, and God said to them, Be fruitful and multiply, and fill the earth, and subdue it: and have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the birds of the air, and over every living thing that moves upon the earth.’

I want to pause for a moment to reflect on what you thought you were doing when these words came to you. Great writers don’t tell us about something. Their writing becomes the thing itself. Is that what you were doing here? Were you writing with a premonitory sorrow over the meaning of these words? In a single sentence you captured humanity’s arrogance, its belief that it owned or had dominion over the earth, and could do anything it liked with it. And that’s what we have done. The planet is marked with the smudge and ugliness of our abuse of it. It is littered with the debris of our greed.

To be fair to us – or to some of us – we have begun to realise what we have done to the planet in our arrogance, and we are trying to make amends. We have started cleaning up the rivers we polluted. We are trying to purify the air over our cities we have saturated with toxic particles. We are even beginning to worry about the effect of losing the species we have rendered extinct. But now some of us are beginning to wonder if it might all be too little too late. A bit like deciding to spring-clean a house on the edge of a cliff that’s about to plunge into the sea because of coastal erosion. It’s the earth, our home, that’s now on the edge of that cliff. All because we didn’t know how to read what you had written. Because we read your words not as a warning, not as a fable that required interpretation, but as an instruction manual to be followed to the letter. Look where it’s got us.

It gets worse. There are literalists out there who believe this is what God actually wants. And because they don’t know how to read, they’ve come up with a god who hates the world so much he is coming soon to destroy it and everything in it. Except them, of course. They’ll be saved as the planet combusts. That’s why they welcome its extinction. ‘Use it before you lose it, the end is nigh,’ they yell, believing their divinely chartered spaceship is standing by to take them to safety. How could I sum up their attitude for you, dear author of Genesis? ‘Fuck the planet, we’re gonna be OK,’ is probably as close as I can get.

So I hope you understand now why I am writing to you. It’s not that I wish you’d been a bit more careful in how you wrote your parable. It’s just that I wish you’d made it clearer what you were doing when you started composing your great fiction. On the other hand, it’s hardly your fault there are so many humans who completely lack imagination. But why do so many of them claim to be religious? Don’t they understand that religion is the oldest art? And that its stories are to be read seriously, but never literally? Enough already.

The good news is that young people everywhere are rebelling against humanity’s God-given right to destroy the earth, their home. Their religion is love of the little blue planet that bore them and sustains them. And they are fighting hard to save it. You’d admire them. You’d want to write something to help them. Or maybe you would just point to something another writer from your own family of artists would say hundreds of years later. His name was Isaiah and these are his words:

‘The wolf shall dwell with the lamb, and the leopard shall lie down with the kid, and the calf and the lion and the fatling together, and a little child shall lead them.’

And you know what, old friend? I’m tempted to read that poem literally!

Richard Holloway

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.