Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

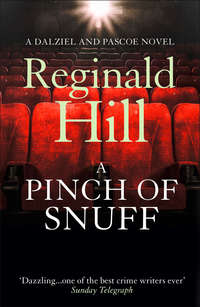

Kitabı oku: «A Pinch of Snuff»

REGINALD HILL

A PINCH OF SNUFF

A Dalziel and Pascoe novel

Copyright

Harper An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street, London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by

HarperCollinsPublishers 1978

Copyright © Reginald Hill 2003

Reginald Hill asserts the moral right to

be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks.

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

Source ISBN 9780586072509

Ebook Edition © July 2015 ISBN 9780007370269

Version: 2015-06-18

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Epigraph

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Keep Reading

About the Author

Also by the Author

About the Publisher

Epigraph

‘If you find you hate the idea of getting out of bed in the morning, think of it this way – it’s a man’s work I’m getting up to do.’

MARCUS AURELIUS: Meditations

Chapter 1

All right. All right! gasped Pascoe in his agony. It’s June the sixth and it’s Normandy. The British Second Army under Montgomery will make its beachheads between Arromanches and Ouistreham while the Yanks hit the Cotentin peninsula. Then …

‘That’ll do. Rinse. Just the filling to go in now. Thank you, Alison.’

He took the grey paste his assistant had prepared and began to fill the cavity. There wasn’t much, Pascoe observed gloomily. The drilling couldn’t have taken more than half a minute.

‘What did I get this time?’ asked Shorter, when he’d finished.

‘The lot. You could have had the key to Monty’s thunderbox if I’d got it.’

‘I obviously missed my calling,’ said Shorter. ‘Still, it’s nice to share at least one of my patients’ fantasies. I often wonder what’s going on behind the blank stares. Alison, you can push off to lunch now, love. Back sharp at two, though. It’s crazy afternoon.’

‘What’s that?’ asked Pascoe, standing up and fastening his shirt collar which he had always undone surreptitiously till he got on more familiar terms with Shorter.

‘Kids,’ said Shorter. ‘All ages. With mum and without. I don’t know which is worse. Peter, can you spare a moment?’

Pascoe glanced at his watch.

‘As long as you’re not going to tell me I’ve got pyorrhoea.’

‘It’s all those dirty words you use,’ said Shorter. ‘Come into the office and have a mouthwash.’

Pascoe followed him across the vestibule of the old terraced house which had been converted into a surgery. The spring sunshine still had to pass through a stained-glass panel on the front door and it threw warm gules like bloodstains on to the cracked tiled floor.

There were three of them in the practice: MacCrystal, the senior partner, so senior he was almost invisible; Ms Lacewing, early twenties, newly qualified, an advanced thinker; and Shorter himself. He was in his late thirties but it didn’t show except at the neck. His hair was thick and black and he was as lean and muscular as a fit twenty-year-old. Pascoe who was a handful of years younger indulged his resentment at the other man’s youthfulness by never mentioning it. Over the long period during which he had been a patient, a pleasant first name relationship had developed between the men. They had shared their fantasy fears about each other’s professions and Pascoe’s revelation of his Gestapo-torture confessions under the drill had given them a running joke, though it had not yet run them closer together than sharing a table if they met in a pub or restaurant.

Perhaps, thought Pascoe as he watched Shorter pouring a stiff gin and tonic, perhaps he’s going to invite me and Ellie to his twenty-first party. Or sell us a ticket to the dentists’ ball. Or ask me to fix a parking ticket.

And then the afterthought: what a lovely friend I make!

He took his drink and waited before sipping it, as though that would commit him to something.

‘You ever go to see blue films?’ asked Shorter.

‘Ah,’ said Pascoe, taken aback. ‘Yes. I’ve seen some. But officially.’

‘What? Oh, I get you. No, I don’t mean the real hard porn stuff that breaks the law. Above the counter porn’s what I mean. Rugby club night out stuff.’

‘The Naughty Vicar of Wakefield. That kind of thing?’

‘That’s it, sort of.’

‘No, I can’t say I’m an enthusiast. My wife’s always moaning they seem to show nothing else nowadays. Stops her going to see the good cultural stuff like Deep Throat.’

‘I know. Well, I’m not an enthusiast either, you understand, but the other night, well, I was having a drink with a couple of friends and one of them’s a member of the Calliope Club …’

‘Hang on,’ said Pascoe, frowning. ‘I know the Calli. That’s not quite the same as your local Gaumont, is it? You’ve got to be a member and they show stuff there which is a bit more controversial than your Naughty Vicars or your Danish Dentists. Sorry!’

‘Yes,’ agreed Shorter. ‘But it’s legal, isn’t it?’

‘Oh yes. As long as they don’t overstep the mark. But without knowing what you’re going to tell me, Jack, you ought to know there’s a lot of pressure to close the place. Well, you will know that anyway if you read the local rag. So have a think before you tell me anything that could involve your mates or even you.’

Which just about defines the bounds of our friendship, thought Pascoe. Someone who was closer, I might listen to and keep it to myself; someone not so close, I’d listen and act. Shorter gets the warning. So now it’s up to him.

‘No,’ said Shorter. ‘It’s nothing to do with the Club or its members, not really. Look, we went along to the show. There were two films, one a straightforward orgy job and the other, well, it was one of these sex and violence things. Droit de Seigneur they called it. Nice simple story line. Beautiful girl kidnapped on wedding night by local loony squire. Lots of nasty things done to her in a dungeon, ending with her being beaten almost to death just before hubbie arrives with rescue party. The squire then gets a taste of his own medicine. Happy ending.’

‘Nice,’ said Pascoe. ‘Then it’s off for a curry and chips?’

‘Something like that. Only, well, it’s daft, and I hardly like to bother anyone. But it’s been bothering me.’

Pascoe looked at his watch again and finished his drink.

‘You think it went too far?’ he said. ‘One for the vice squad. Well, I’ll mention it, Jack. Thanks for the drink, and the tooth.’

‘No,’ said Shorter. ‘I’ve seen worse. Only in this one, I think the girl really did get beaten up.’

‘I’m sorry?’

‘In the dungeon. The squire goes berserk. He’s got these metal gauntlets on, from a suit of armour. And a helmet too. Nothing else. It was quite funny for a bit. Then he starts beating her. I forget the exact sequence but in the end it goes into slow motion; they always do, this fist hammers into her face, her mouth’s open – she’s screaming, naturally – and you see her teeth break. One thing I know about is teeth. I could swear those teeth really did break.’

‘Good God!’ said Pascoe. ‘I’d better have another of these. You’re saying that … I mean, for God’s sake, a mailed fist! How’d she look at the end of the film? I’ve heard that the show must go on, but this is ridiculous!’

‘She looked fine,’ said Shorter. ‘But they don’t need to take the shots in the order you see them, do they?’

‘Just testing you,’ said Pascoe. ‘But you must admit it seems daft! I mean, you’ve no doubt the rest of the nastiness was all faked?’

‘Not much. Not that they don’t do sword wounds and whip lashes very well. But I’ve never seen a real sword wound or whip lash! Teeth I know. Let me explain. The usual thing in a film would be, someone flings a punch to the jaw, head jerks back, punch misses of course, on the sound track someone hammers a mallet into a cabbage, the guy on the screen spits out a mouthful of plastic teeth, shakes his head, and wades back into the fight.’

‘And that’s unrealistic?’

‘I’ll say,’ said Shorter. ‘With a bare fist it’s unrealistic, with a metal glove it’s impossible. No, what would really happen would be dislocation, probably fracture of the jaw. The lips and cheeks would splatter and the teeth be pushed through. A fine haze of blood and saliva would issue from the mouth and nose. You could mock it up, I suppose, but you’d need an actress with a double-jointed face.’

‘And this is what you say happened in this film.’

‘It was a flash,’ said Shorter. ‘Just a couple of seconds.’

‘Anybody else say anything?’

‘No,’ admitted Shorter. ‘Not that I heard.’

‘I see,’ said Pascoe, frowning. ‘Now, why are you telling me this?’

‘Why?’ Shorter sounded surprised. ‘Isn’t it obvious? Look, as far as I’m concerned they can mock up anything they like in the film studios. If they can find an audience, let them have it. I’ll watch cowboys being shot and nuns being raped, and rubber sharks biting off rubber legs, and I’ll blame only myself for paying the ticket money. No, I’ll go further though I know our Ms Lacewing would pump my balls full of novocaine if she could hear me! It doesn’t all have to be fake. If some poor scrubber finds the best way to pay the rent is to let herself be screwed in front of the cameras, then I won’t lose much sleep over that. But this was something else. This was assault. In fact the way her head jerked sideways, I wouldn’t be surprised if it ended up as murder.’

‘Well, there’s a thing,’ murmured Pascoe. ‘Would you stake your professional reputation?’

Shorter, who had been looking very serious, suddenly grinned.

‘Not me,’ he said. ‘I really was convinced that John Wayne died at the Alamo, But it’s bothered me a bit. And you’re the only detective-inspector I know, so now it can bother you while I get back to teeth.’

‘Not mine,’ said Pascoe smugly. ‘Not for six months.’

‘That’s right. But don’t forget you’re due to have the barnacles scraped off. Monday, I think. I’ve fixed you up with our Ms Lacewing. She’s a specialist in hygiene, would you believe?’

‘I also gather that she too doesn’t care what goes on at the Calliope Kinema Club,’ said Pascoe.

‘What? Oh, of course, you’d know about that. The picketing, you mean. She’s tried to get my wife interested in that lot but no joy there, I’m glad to say. No, if I were you I’d keep off the Calli while she’s got you in the chair. On the other hand I’m sure she’d be fascinated by any plans Bevin might have for harnessing female labour in the war effort.’

‘Shorter,’ said Detective-Superintendent Andrew Dalziel reflectively. ‘Does your fillings in a shabby mac and a big hat, does he?’

‘Pardon?’ said Pascoe.

‘The blue film brigade,’ said Dalziel, scratching his gut.

‘I managed to grasp the reference to the shabby mac,’ said Pascoe.

‘Clever boy. Well, they need the big hats to hold on their laps.’

‘Ah,’ said Pascoe.

‘Of course it’s a dead giveaway when they stand up. Jesus, my guts are bad!’

Scatophagous crapulence, diagnosed Pascoe, but he kept an expression of studied indifference on his face. On his bad days Dalziel was quite unpredictable and it was hard for his inferiors to steer a path between overt and silent insolence.

‘I reckon it’s an ulcer,’ said Dalziel. ‘It’s this bloody diet. I’m starving the thing and it’s fighting back.’

He thumped his paunch viciously. There was certainly less of it than there had been a couple of years earlier when the diet had first begun. But the path of righteousness is steep and there had been much backsliding and strait is the gate and it would still be a tight squeeze for Dalziel to get through.

‘Shorter,’ reminded Pascoe. ‘My dentist.’

‘Not one for us. Mention it to Sergeant Wield, though. How’s he shaping?’

‘All right, I think.’

‘Shown his face at the Calli, has he? That’s why I picked him, that face. He’ll never be a master of disguise, but, Christ, he’ll frighten the horses!’

This was a reference to (a) Sergeant Wield’s startling ugliness and (b) the Superintendent’s subtle tactic for satisfying both parties to a complaint. The Calliope Kinema Club had opened eighteen months earlier and after an uneasy period as a sort of art house it had finally settled for a level of cine-porn a couple of steps beyond what was available at Gaumonts, ABCs and on children’s television. All might have been well had the Calli known its place, wherever that was. But wherever it was, it certainly wasn’t in Wilkinson Square. Unlike most centrally situated monuments to the Regency, Wilkinson Square had not relaxed and enjoyed the rape of developers and commerce. Even the subtler advances of doctors’ surgeries, solicitors’ chambers and civil servants’ offices had been resisted. It was true that some of the larger houses had become flats and one had even been turned into a private school which for smartness of uniform and eccentricity of curriculum was not easily matched, but a large proportion of the fifteen houses which comprised the Square remained in private occupation. Even the school was forgiven as a necessary antidote to the creeping greyness of post-war education based on proletarian envy and Marxist subversion. No parent of sense with a lad aged six to eleven could be blamed for supporting this symbol of a nation’s freedoms, whatever the price. The price included learning to add in pounds, shillings and pence and being subjected to Dr Haggard’s interesting theories on corporal punishment, but it was little to pay for the social kudos of having a Wilkinson House certificate.

What inefficiency and paedophobia could not achieve, inflation and a broken economy did, and in the mid-seventies so many parents had a change of educational conscience that the school finally closed. The inhabitants of Wilkinson Square watched the house with interest and suspicion. The best they could hope for was expensive flats, the worst they feared was NALGO offices.

The Calliope Kinema Club was a shattering blow cushioned only by the initial incredulity of those receiving it. That such a coup could have taken place unnoticed was shock enough; that Dr Haggard could have been party to it defied belief. But it had and he was. His master stroke had been to change the postal address of the building. Wilkinson House occupied a corner site and one side of the house abutted on Upper Maltgate, a busy and noisy commercial thoroughfare. Here, down a steep flight of steps and across a gloomy area, was situated the old tradesman’s entrance through which postal and most other deliveries were still made. Dr Haggard requested that his house be henceforth known as 21A Upper Maltgate. There was no difficulty, and it was as 21A Upper Maltgate that the premises were licensed to be used as a cinema club while the vigilantes of the Square slept and never felt their security being undone.

But once awoken, their wrath was great. And once the nature of the entertainments being offered at the Club became clear, they launched an attack whose opening barrage in the local paper was couched in such terms that applications for membership doubled the following week.

Legally the Club was in a highly defensible position. The building satisfied all the safety regulations and the Local Authority had issued a licence permitting films to be shown on the premises. The films did not need to be certificated for public showing, though many of them were, and even those such as Droit de Seigneur which were not had so ambiguous a status under current interpretation of the obscenity laws that a successful prosecution was most unlikely.

In any case, as the Wilkinson Square vigilantes bitterly pointed out, Haggard clearly had strong support in high places and they had to content themselves with appealing against the rates and ringing the police whenever a car door slammed. Most of them hadn’t known whether to raise a radical cheer or a reactionary eyebrow when WRAG, the Women’s Rights Action Group, had joined the fray. Sergeant Wield, who had been given the job of looking into complaints from both sides, was summoned by Haggard and later three members of WRAG, including Ms Lacewing, Jack Shorter’s partner, were fined for obstructing the police in the execution, etc. This confirmed the vigilantes’ instinct that the rights of women and the rights of property owners had nothing in common and a potentially powerful alliance never materialized. But the pressures remained strong enough for Sergeant Wield to be currently engaged in preparing a full report on the Calli and all complaints against it. Pascoe felt a little piqued that his own contribution was being so slightingly dismissed.

‘So I just ignore Shorter’s information?’ he said.

‘What information? He thinks some French bird got her teeth bust in a picture? I’ll ring the Sûreté if you like. No, the only thing interests me about Mr Shorter is he likes dirty films.’

‘Oh come on!’ said Pascoe. ‘He went along with a friend. Where’s the harm? As long as it doesn’t break the law, what’s wrong with a bit of titillation?’

‘Titillation,’ repeated Dalziel, enjoying the word. ‘There’s some jobs shouldn’t need it. Doctors, dentists, scout-masters, vicars – when any of that lot start needing titillation, watch out for trouble.’

‘And policemen?’

Dalziel bellowed a laugh.

‘That’s all right. Didn’t you know we’d been made immune by Act of Parliament? They’ve got a council, these dentists? No doubt they’ll sort him out if he starts bothering his patients. I’d keep off the gas if I were you.’

‘He’s a married man,’ protested Pascoe, though he knew silence was a marginally better policy.

‘So are wife-beaters,’ said Dalziel. ‘Talking of which, how’s yours?’

‘Fine, fine,’ said Pascoe.

‘Good. Still trying to talk you out of the force?’

‘Still trying to keep me sane within it,’ said Pascoe.

‘It’s too bloody late for most of us,’ said Dalziel. ‘I get down on my knees most nights and say, “Thank you, Lord, for another terrible day, and stuff Sir Robert.”’

‘Mark?’ said Pascoe, puzzled.

‘Peel,’ said Dalziel.

Chapter 2

Pascoe was surprised at the range of feelings his visit to the Calliope Kinema Club put him through.

He felt furtive, angry, embarrassed, outraged, and, he had to confess, titillated. He was so immersed in self-analysis that he almost missed the teeth scene. It was the full frontal of a potbellied man wearing only a helmet and gauntlets that triggered his attention. There was a lot of screaming and scrabbling, all rather jolly in a ghastly kind of way, then suddenly there it was; the mailed fist slamming into the screaming mouth, the girl’s face momentarily folding like an empty paper bag, then her naked body falling away from the camera with the slackness of a heavyweight who has run into one punch too many. Cut to the villain, towering in every sense, with sword raised for the coup de grâce, then the door bursts open and enter the hero, by some strange quirk also naked and clearly a match for tin-head. The girl, very bloody but no longer bowed, rises to greet him, and the rest is retribution.

When the lights were switched on Pascoe, who had arrived in the dark, looked around and was relieved to see not a single large hat. The audience numbered about fifty, almost filling the room, and were of all ages and both sexes, though men predominated. He recognized several faces and was in turn recognized. There would be some speculation whether his visit was official or personal, he guessed, and he did not follow the others out of the viewing room but sat and waited till word should reach Dr Haggard.

It didn’t take long.

‘Inspector Pascoe! I didn’t realize you were a member.’

He was a tall, broad-shouldered man with a powerful head. His hair was touched with grey, his eyes deep set in a noble forehead, his rather overfull lips arranged in an ironic smile. Only a pugilist twist of the nose broke the fine Roman symmetry of that face. In short, it seemed to Pascoe to display those qualities of authoritarian, intellectual, sensuous brutality which were once universally acknowledged as the cardinal humours of a good headmaster.

‘Dr Haggard? I didn’t realize we were acquainted.’

‘Nor I. Did you enjoy the show?’

‘In parts.’

‘Parts are what it’s all about,’ murmured Haggard. ‘Tell me, are you here in any kind of official capacity?’

‘Why do you ask?’ said Pascoe.

‘Simply to help me decide where to offer you a drink. Our members usually foregather in what used to be the staff room to discuss the evening’s entertainment.’

‘I think I’d rather talk in private,’ said Pascoe.

‘So it is official.’

‘In part,’ said Pascoe, conscious that this was indeed only a very small part of the truth. Shorter’s story had interested him, Dalziel’s lack of interest the previous day had piqued him, Ellie was representing her union at a meeting that night, television was lousy on Thursdays, and Sergeant Wield had been very happy to supply him with a membership card.

‘Then let us drink in my quarters.’

They went out of the viewing room, which Pascoe guessed had once been two rooms joined together to make a small school assembly hall, and climbed the stairs. Sounds of conversation and glasses as from a saloon bar followed them upstairs from one of the ground-floor rooms. The Wilkinson Square vigilantes had made great play of drunkards falling noisily out of the Club late at night and then falling noisily into their cars, which were parked in a most inconsiderate manner all round the Square. Wield had found no evidence to support these assertions.

Haggard did not pause on the first-floor landing but proceeded up the now somewhat narrower staircase. Observing Pascoe hesitate, he explained, ‘Mainly classrooms here. Used for storage now. I suppose I could domesticate them again but I’ve got so comfortably settled aloft that it doesn’t seem worth it. Do come in. Have a seat while I pour you something. Scotch all right?’

‘Great,’ said Pascoe. He didn’t sit down immediately but strolled around the room, hoping he didn’t look too like a policeman but not caring all that much if he did. Haggard was right. He was very comfortable. Was the room rather too self-consciously a gentleman’s study? The rows of leather-bound volumes, the huge Victorian desk, the miniatures on the wall, the elegant chesterfield, the display cabinet full of snuff-boxes, these things must have impressed socially aspiring parents.

I wonder, mused Pascoe, pausing before the cabinet, how they impress the paying customer now.

‘Are you a collector?’ asked Haggard, handing him a glass.

‘Just an admirer of other people’s collections,’ said Pascoe.

‘An essential part of the cycle,’ said Haggard. ‘This might interest you.’

He reached in and picked up a hexagonal enamelled box with the design of a hanging man on the lid.

‘One of your illustrious predecessors. Jonathan Wild, Thief-taker, himself taken and hanged in 1725. Such commemorative design is quite commonplace on snuffboxes.’

‘Like ashtrays from Blackpool,’ said Pascoe.

‘Droll,’ said Haggard, replacing the box and taking out another, an ornate silver affair heavily embossed with a coat of arms.

‘Mid-European,’ said Haggard. ‘And beautifully airtight. This is the one I actually keep snuff in. Do you take it?’

‘Not if I can help it.’

‘Perhaps you’re wise. In the Middle Ages they thought that sneezing could put your soul within reach of the devil. I should hate you to lose your soul for a pinch of snuff, Inspector.’

‘You seem willing to take the risk.’

‘I take it to clear my head,’ smiled Haggard. ‘Perhaps I should take some now before you start asking your questions. I presume you have some query concerning the Club?’

‘In a way. It’s a bit different from teaching, isn’t it?’ said Pascoe, sitting down.

‘Is it? Oh, I don’t know. It’s all educational, don’t you think?’

‘Not a word some people would find it easy to apply to what goes on here, Dr Haggard,’ said Pascoe.

‘Not a word many people find it easy to apply to much of what goes on in schools today, Inspector.’

‘Still, for all that …’ tempted Pascoe.

Haggard regarded him very magisterially.

‘My dear fellow,’ he said. ‘When we’re much better acquainted, and you have proved to have a more than professionally sympathetic ear, and I have been mellowed by food, wine and a good cigar, then perhaps I may invite you to contemplate the strange flutterings of my psyche from one human vanity to another. Should the time arrive, I shall let you know. Meanwhile, let’s stick with your presence here tonight. Have my neighbours undergone a new bout of hysteria?’

‘Not that I know of,’ said Pascoe. ‘No, it’s about one of your films. One I saw tonight. Droit de Seigneur.’

‘Ah yes. The costume drama.’

‘Costume!’ said Pascoe.

‘Did the nudity bother you?’ said Haggard anxiously.

‘I don’t think so. Anyway it was the assault scene I wanted to talk about, where the girl gets beaten up.’

‘You found it too violent? I’m astounded.’

‘The scene was brought to my attention …’

‘By whom?’ interrupted Haggard. ‘Has he not seen A Clockwork Orange? The Exorcist? Match of the Day?’

‘I would like you to be serious, Dr Haggard,’ said Pascoe reprovingly. ‘What do you know about the making of these films?’

‘In general terms, very little. You probably know more yourself. I’m sure the diligent Sergeant Wield does. I am merely a showman.’

‘Of course. Look, Dr Haggard, I wonder if it would be possible to see part of that film again. It’ll help me explain what I’m doing here.’

Haggard finished his drink, then nodded.

‘Why not? I’m intrigued. You could always gatecrash again, of course, but I suppose that might compromise your reputation. Besides, we only have that film until the weekend, so let’s see what we can do.’

Downstairs again, Haggard left Pascoe in the viewing room and disappeared for a few moments, returning with a small triangular-faced man with large hairy-knuckled hands, one of which was wrapped round a pint tankard.

‘Maurice, this is Inspector Pascoe. Maurice Arany, my partner and also, thank God, my projectionist. I am mechanically illiterate.’

They shook hands. It would have been easy, thought Pascoe, to develop it into a test of strength, but such games were not yet necessary.

As well as he could he described the sequence he wished to see, and Arany went out. Haggard switched off the lights and they sat together in the darkness till the screen lit up. Arany hit the spot with great precision and Pascoe let it run until the entry of the vengeful husband.

‘That’s fine,’ he said and Haggard interposed his arm into the beam of light and the picture flickered and died.

‘Well, Inspector?’ said Haggard after he had switched on the lights.

‘My informant reckons that was for real,’ said Pascoe diffidently.

‘All of it?’ said Haggard.

‘The punch that knocks the girl down.’

‘How extraordinary. Shall we look again? Maurice!’

They sat through the sequence once more.

‘It’s quite effective, though I’ve seen better,’ said Haggard. ‘But on what grounds would you claim it was real, if by real you mean that some unfortunate girl really did get punched?’

‘I don’t know,’ admitted Pascoe. ‘It has a quality … I’ve seen a few fights, and that kind of …’

He tailed off, uncertain if he was speaking from even the narrowest basis of conviction. If he had seen the film without Shorter’s comments in his mind, would he have paid any special attention to the sequence? Presumably hundreds of people (thousands?) had sat through it without unsuspending their disbelief.

‘I’ve seen people burnt alive, decapitated, disembowelled and operated on for appendicitis, all I hasten to add in the commercial cinema,’ said Haggard. ‘So far as my own limited experience of such matters permitted me to judge, I was completely convinced of the verisimilitude of these scenes. I shouldn’t have thought dislodging a few teeth was going to present the modern director with many problems.’

‘No,’ said Pascoe. He was beginning to feel a little foolish, but under Dalziel’s tutelage he had come to ignore such social warning cones.

‘Can I see the titles, please?’ asked Pascoe.

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.