Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

Kitabı oku: «A Curious Boy»

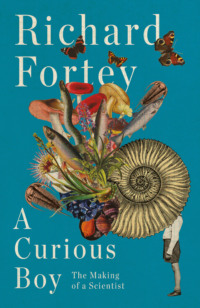

A CURIOUS BOY

The Making of a Scientist

Richard Fortey

Copyright

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

HarperCollinsPublishers

1st Floor, Watermarque Building, Ringsend Road

Dublin 4, Ireland

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2021

Copyright © Richard Fortey 2021

Richard Fortey asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

Cover design: gray318

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins

Source ISBN: 9780008323967

Ebook Edition © January 2021 ISBN: 9780008323981

Version: 2021-01-14

Dedication

To Heather and David,

with love and gratitude

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

List of Illustrations

1 The Trout

2 Eggs and After

3 The Chemi-shed

4 The Ammonite

5 Fungus

6 Entr’acte

7 Flowers

8 Three Lobes

9 Getting Serious

10 The Life Scientific

Footnotes

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Also by Richard Fortey

About the Publisher

Illustrations

| Here | The definitive brown trout curated by J. Cooper & Sons. |

| Here | A predated song thrush egg picked up from my wood. |

| Here | A funnel and a few reagent bottles – all that survives from my chemical boyhood. |

| Here | My first fossil, the Jurassic ammonite Parkinsonia. |

| Here | Fossils of sea urchins were common in the chalk at the edge of the Berkshire Downs. |

| Here | My old woven basket, used for collecting fungi. |

| Here | My basket, fully laden. |

| Here | A sketch of Forge Cottage, Ham, Wiltshire, made by a school friend in the early sixties. |

| Here | Fifty years of continuous botanical use. A page from my Collins Pocket Guide to Wild Flowers, with two sightings of grass of Parnassus duly recorded. |

| Here | The large Devonian trilobite Drotops from Morocco. |

| Here | In Spitsbergen. |

| Here | My drawings of the special graptolite from the Ordovician rocks of Spitsbergen from my first solo scientific paper. |

| Here | The Arctic privy. |

| Here | With Lehi Hintze in Nevada in 1972. |

1

The Trout

On the wall of my study a trout in a glass case is facing upstream. Its mouth is slightly agape as it gulps the clear, pure water of the chalk river in which it lived. The fish is not swimming; rather, it is perfectly maintaining its position in a busy current. In life, its fins and tail swished gently to keep it exactly where it wanted to remain, alert for the small prey that nourished it to such generous proportions. Its skin glistens, not in the blatant fashion of the crudely stuffed fishes that decorate some waterside pubs along the River Thames, but sleek and subtle, a slick and a lick of varnish, just enough to suggest the slippery sides of the living animal, but not so much as to point up its artificial afterlife. It is a brown trout, a wild fish, its upper flanks broadly dotted as if by a leisurely crayon, belly silvery white and tessellated with hundreds of fine scales. Nor does it hang all by itself. The preparator has carefully placed model riverweed beneath the fish – not just plonked down, but rather drawn out as if played like hair in a current. The direction of the weed points up the rush of the water, and reinforces the convincing response of the fish to its ambient flow. This is a carefully curated specimen. The front of the glass case is gently bowed outwards and framed by a thin line of gold leaf. At the bottom of the frame – also picked out in gold – ‘TROUT 4 lb 13 oz. Caught by F. A. Fortey 13 May 1947 River Gade.’ Not long after the Second World War, my father caught this fish from the transparent waters of a stream running through the Chiltern Hills, north-west of London. I was a one-year-old baby at the time.

The trout became an heirloom, taken for granted for half a century. It may have hung in one of my father’s two fishing-tackle shops as an encouragement – more likely a challenge – to aspiring anglers. The time came when I inherited it and it became part of the paraphernalia that moves with your family from house to house. On one of these changes of address the removal man was carrying the fish to the truck when he suddenly stopped in his tracks, gawped, and exclaimed: ‘Blimey! It’s a Cooper!’ I had no idea what a ‘Cooper’ was. ‘In your fish world,’ said the removal man, gravely, ‘a Cooper is like a Stradivarius.’ He was something of a connoisseur. Now that it had been identified I discovered a discreet little label at the back of the case: ‘Preserved by J. Cooper & Sons, 78, Bath Road, Hounslow’. No commonplace ‘stuffing’ for a Cooper & Sons fish, what you got instead was ‘preservation’. These artists preserved the consummate moments of a fisherman’s career. I noticed for the first time the subtleties of taxidermy that lifted this fish from the merely stuffed.

The definitive brown trout curated by J. Cooper & Sons.

That trout must have been an exceptional catch. There is no ‘brownie’ nearly as substantial swimming in the River Gade in the twenty-first century; water extraction for thirsty Watford and insatiable London has much reduced the flow of such spring-fed rivers originating from the chalk of the Chiltern Hills. The Watford Piscators have not been able to find the equal of my father’s fish in their records, so when he caught it I suspect it was a record-breaker. It was worth immortalising by commissioning the Coopers to work their magic, even when money must have been short. In the 1940s, after the global conflict, petrol was expensive and rationed, so a short expedition to the river in motorbike and sidecar from the flat in West London was not to be taken lightly. The Strad of the trout firmament remains a serious item, a treasure.

When I was growing up, trout were important. I spent a lot of time watching them. The River Lambourn runs south-eastwards from the famous small racing town bearing the same name, perched high on the chalk in southern England. The bare downs around the town are lined with post-and-rail fences and open rides, where fast and elegant horses are to be glimpsed from time to time. The humble houses in the town built of tough sarsen stones belie the big money that comes to the owners and trainers of a successful nag. Spring water wells up from the depths to water horse and man alike. The spring-fed River Lambourn is another of those special streams with water as cold and pure as it is pellucid, the natural home of the brown trout. This small river joins the greater River Kennet at Newbury, and a few miles north-west of that town I first remember watching fish. In the little village of Boxford I hung on tiptoe over the flint-and-brick bridge looking at the Lambourn trout below. The stream flowed fast here, and just as in the Cooper & Sons ‘preservation’ the trout often held a position facing upstream. The stream bed was verdant with water weed: crowfoot with dark, thin leaves making bunches that waved like windblown locks of hair in the current, starwort growing in cheerful green cushions on muddier patches in still water near the bank, and stiffer sedges that bent erratically under the bidding of the water’s flux. The spots on the trout disguised the fish against their weedy background. They could sometimes almost disappear, and then reveal themselves suddenly with a twitch of the tail, or by a sudden realignment in the current. If disturbed by a tossed stone they might shoot off to lurk under a bank or negotiate a deeper pool. From time to time a grayling would appear as a silvery flash, blatantly displaying its prominent dorsal fin. The river and its fishes were an endless source of variety while essentially forever remaining the same. The timeless emotion that consumed me was similar to contemplating a real fire in a real hearth: flames lick and mutate, and there’s nothing to distract you except endless distraction.

I spent quite a chunk of my childhood half wild in the countryside. Although we lived in the West London suburb of Ealing, most summer weekends the family escaped to Berkshire and to the fly fishing. Even now I wonder whether I am more urban or more rural. By the time I was eight or nine my father had joined the Piscatorial Society, which allowed him to fish several chalk streams besides the River Lambourn: a stretch of the River Kennet not far from Newbury, and a piece of the River Itchen just outside the ancient city of Winchester. I had a chance to follow the dedicated fisherman along the banks of these famous rivers, honing my skills at spotting fishes lurking under the waving fronds of weed, or observing one of them occasionally rise to sip a fly from the gliding surface of the water, as delicately as my maiden aunts tasted Sunday afternoon tea; hardly a sound, just a small suck of the lips. The skill of the dry-fly fisherman is to place the right kind of artificial fly (with its hidden hook) just where the trout will be tempted to take it. My father was consummately skilful at this. He could place a ‘fly’ on a penny. The art was to keep the ‘fly’ aloft at the tip of the thinnest part of the line, by elegant aerial swishes back and forth, until just the right length of line had been conjured from the reel to drop the ‘fly’ on to the point in the stream where it would pass over the lurking fish. If the trout were tempted to rise to the bait above it the angler must strike at precisely the right moment to snare the hook in the fish’s mouth. A moment too soon and the fish will scoot away. Larger fish had survived the attentions of many eager anglers to become more cautious – so the bigger the prize the harder the catch. Record fish have been scarred by experience. The luck of the Coopers’ 4 pound 13-ouncer from the River Gade finally ran out when my father came along.

The imitation trout flies used on chalk streams are not the gaudy lures beloved of salmon fishermen that bear little resemblance to real, living insect species. Instead, the standard ‘flies’ of the chalk-stream anglers bear modest, understated names like Pale Watery or Olive Dun. They are true approximations to real species, and they are comparatively tiny – little tan-coloured scraps of things. They are not even flies in the scientific, entomological sense – they belong to a different insect order (Ephemeroptera[1]) from houseflies and their prolific ilk (Diptera). Savvy old brown trout are not easily fooled by show alone; they need the real thing. Chalk-stream trout anglers regard their piscatorial skills as the quintessence of the art. To be a great trout fisherman on these challenging rivers is to understand the psychology of the fishes, the entomology of their favourite snacks, the physics of flow, and to match that understanding with flawless skill in casting and striking. Eventually landing the fish is the least of it, although wily and experienced fishes have been known to escape even after they have taken a hook by scuffling through the weeds. A certain snobbery on the part of skilled trout aficionados is perhaps only to be expected, and fishing rights along elite stretches of river do indeed come with a huge premium. The River Test in Hampshire lies at the apex of this hierarchy and the Houghton Club near Stockbridge lies at the apex of that apex. This is arguably the most exclusive club in the world, where a fortune alone will not buy you entry without a deft command of the subtleties of fly fishing. My father had the skill, but never had the money.

There were a few days every year when all the decorum of chalk-stream fishing went to the wall. When the mayfly hatched trout went berserk. This ‘fly’ was substantial – half a dozen Olive Duns rolled into one fat body. After a year of fattening up as larvae on the stream bed the mayfly simultaneously attained their adult form to fly and mate in the warm air of early May, an adult life of just a day. These ephemeral insects had been doing just this since the time of the dinosaurs. During a good year the air was thick with mayflies, dancing up and down. They landed on outstretched arms like transparent-winged butterflies. This small boy examined them minutely, observed how their wings folded back as they landed, noticed that there were two long whip-like hairs at the end of the body, and tossed them into the air again to see them dancing. When they landed on the water even the shyest, most reticent trout could not resist the succulent bodies of breeding mayflies. Now the gulps of the fish were readily audible, and occasionally a whole shining body churned and twisted in pursuit. Fly fishermen look forward to mayflies as small children long for Christmas.

If William Wordsworth was right that ‘the child is father of the man’ then I was first made on a riverbank. Did my early life, linked so intimately to trout, somehow dictate the person I became? That small boy in grey flannel shorts doggedly tracking a virtuoso father along a chalk stream eventually became a scientist and writer. The roots of my own life were nourished on summer days in the Berkshire countryside just pottering about and wading through marshes. My recall of that young boy is often vague. However, I do precisely recall early sensations and observations: the slightly tacky feel of the mayfly limbs stuck to my arms, the dank smell of waterweed, the frenetic scuttling of freshwater shrimps. As far as I know, no other boy from Ealing had such a curious connection to chalk streams. They didn’t have freshly fried brown trout for breakfast. This was almost the only cooking my father ever did: brown trout fried rapidly till the skin went golden, but all the luscious taste kept inside; nothing could have been more scrumptious.

I did not savour that taste again until thirty years later when I persuaded a young man to part with his catch of sea trout in western Newfoundland. Then that special deliciousness immediately caught the past with poignant accuracy. I remembered how I used to fillet the trout myself, removing head, guts and swim bladder in a single cut, and how a slippery fish once shot from my hands as if it were still alive. If I am to explore how that small boy became a scientist I have to follow prompts like taste or smell, revive half-forgotten memories, stir some murky depths. There are no diaries for me to refer to, and the exact chronology of many events has faded over time. A few important moments stand out as transformative markers, but I cannot lay claim to a sense of inevitable destiny. I did not dream of cracking the secrets of prime numbers when I was ten, nor did I anticipate the discovery of a new fundamental particle when I was thirteen. Serial enthusiasms were more the ticket, and I still believe in the inexhaustible interest of the natural world. There were times when happenstance determined my future direction, and I wonder what would have changed with a different spin of the coin. What I do have as tangible evidence is that ‘preserved’ fish from Cooper & Sons, a physical prompt to conduct me back to the past. There are other portals that open on to my younger self – a scuffed book or an ammonite – that trace how an instinctive naturalist developed into a professional palaeontologist; but that small boy wandering along the riverbank is still in there somewhere, always waiting for something new to turn up, as alert as a kingfisher with a minnow in its sights.

The temptation is to portray those riverine days as somehow bathed in sunlight and serendipitous discovery, but there were difficult moments. Fishing beats leased to the Piscatorial Society were policed by gamekeepers with relentless vigilance; they took no prisoners. By the River Kennet damp pathways led between coarse tussocks of sedge and treacherous ditches full of reeds that were far taller than the boy wandering from one distributary of the river to find another. Suddenly, a gamekeeper’s ‘larder’ loomed up without warning – a crude wooden contraption on which the guardian of the fishing had hammered the bodies of predators he deemed a menace. Weasels and stoats endured a ham-fisted crucifixion, magpies drooped like wounded umbrellas, crows hung limp, all lustre faded from their feathers. But the larder was alive: the corpses heaved with maggots, while big black beetles climbed the scaffolding of the corpses in search of some unclaimed patch of putrescence. The stench made me reel. In a horror movie the scene would have been announced by a sharp discord from full orchestra. But I was curiously transfixed by this tableau of death. I suppose the theory was that such a grisly display would deter predators. It certainly deterred one small boy. I don’t know how long I stood there, but the spell was broken when a wing of one of the birds just fell off, and several creatures scuttled on spindly legs from the fallen limb into the surrounding grass.

Kennet evenings were a different matter. Outside the mayfly orgy the favoured time for a trout fisherman was, and remains, the ‘evening rise’. It seems that trout like to taste a fly or two as the sun dips below the horizon. A strange stillness embraced the river at this time. Moths emerged from their daytime hiding places and fluttered all white and silent over the water, which assumed a profound and almost greasy blackness as the light left it alone. The swish of the rod accompanied the faintest gurglings of the restless stream. If there could be such a thing as perfect peace, then this was it. The rise was most satisfactory when the weather was clear and warm, and there were occasions when the prospect of an interesting evening would entail a hectic drive from London to catch the fading light. My father habitually drove too fast. We would, however, always have to stop the car once, and sometimes twice, to wipe dead insects from the car windscreen. This simple plate of glass was a way of randomly sampling what was flying as dusk approached – and there was a lot of it. The most conspicuous insects were obviously succulent moths, but there was also a fuzz of lesser beasts: mosquitoes or gnats, perhaps. Thousands of them.

That is what has changed. When I drove down some of the same roads recently, in the dying light, I arrived at my destination with perhaps a dozen insects on my windscreen, and only one moth. Maybe the aerodynamics of windscreens have changed during my lifetime to kill fewer insects, but I am certain that their flutterings do not catch the headlights any more, regardless of whether they finish up as dead bodies. If a symbol were needed of the decline of the country habitat since the 1950s then a clear windscreen would be hard to beat. The recent reduction in the number of insectivores of many kinds hardly comes as a surprise. Blame is easy to dish around, but the hegemony of monocultures on ranch-style farms and the liberal use of insecticides is going to be on the list of prime suspects. Sometimes, a long memory is a recipe for gloom.

What of the River Lambourn? In 2015 I went back to Boxford, a mile or two north-west of a now expanded Newbury, to revisit the chalk stream that had nourished my first awareness of the richness of life. The old bridge was still there, with the clear, rushing stream beneath it. A grey wagtail welcomed me back, bobbing and flitting like a coquette. The village had changed completely. When my parents bought a simple, thatched cottage in Boxford almost sixty years ago there was no mains drainage. Primrose Cottage was pretty enough, but we did our business in a closet, sterilised by something called Elsan, and then occasionally buried the digested produce in the vegetable garden. I recall the lush gratitude of the cabbages. Nowadays, Boxford is as smart as Chelsea. It looks positively groomed. The hedges that surround the old cottages are shaved as close as a glamour model’s armpits. Somehow, the village no longer feels like part of the countryside, more a lifestyle accessory. However, while the clean river still flows vigorously, all is not lost.

I had joined a team from the Environment Agency that has been monitoring the health of the River Lambourn. Boxford Meadows is now a Site of Special Scientific Interest. One of my early sources of biological wonder now has the imprimatur of an official classification. In wellington boots I followed the team as they counted the fish that were retrieved from a stretch of water they had selected for sampling. Crack willows still leaned precariously over the rippling stream, and the water crowfoot was sporting its white, buttercup-like flowers in profusion, each bloom held aloft from the water to be pollinated in the air just like any other flower. The good news was that there were still wild brown trout in the Lambourn. The biologists used ‘electric fishing’ to take a census of the fishy life. Place electrodes into the water from a small punt and native species cannot resist being attracted to the positive pole. The lure of electricity turns them into zombies drifting towards the electrode – where they soon become statistics, before being returned to the water unharmed. Along with the trout I saw the brook lamprey (the lampern), a fish so primitive it does not even have a proper jaw. It looked superficially like a small eel, until I noticed the strange lines of gill openings behind the head. Like the mayfly, it is a fugitive from deep time. Some species failed to turn up, like the ‘miller’s thumb’ (Cottus gobio), a small, fat-headed, spiky fish I caught long ago using a small net poked between the flint pebbles that covered the bed of the river. Then an unwelcome stranger barged into the inventory: the American signalling crayfish, Pacifastacus leniusculus, as big as the palm of my hand. When I was a child, a smaller, native, white-clawed crayfish (Austropotamobius pallipes) was there instead. I remember picking one up by the carapace just behind its claws, which opened like miniature nutcrackers when the creature left the water. Our own modest crustacean has since become virtually extinct, bullied by its distant cousin from the other side of the Atlantic Ocean. The signaller was introduced to Britain in the 1970s as a ‘cash crop’ and has since relentlessly advanced into all streams with pure running water, where it has exterminated its native ecological rival. It is voracious – even cannibalistic – and I cannot help wondering whether the absence of the ‘miller’s thumb’ might also have something to do with this interloper.

Nor was every trout a ‘brownie’. A few rainbow trout among the sporting fish identified themselves by red stripes running along their flanks and dense spots above. The rainbow is the farmed trout familiar from every supermarket. They originated from cool streams in North America that flow into the Pacific Ocean, and they, too, have become naturalised in Britain. Many trout-fishing clubs stock their rivers with rainbow trout grown in stew-ponds to give their members an easier catch: they grow faster than the native species, and raised fish are less wily. My father rather despised them. He believed only brown trout truly tested the artistry of the fly fisherman, and the wilier the better. We rarely ate rainbow trout. The soft pink flesh of the wild brown trout, nurtured on freshwater shrimp and flies and snails, was considered a far superior food. It was many years before I could bring myself to purchase a pack from a supermarket, by which time my memories of the wild fish from the chalk streams had begun to fade; but I still knew something was missing.

My day by the River Lambourn left me feeling curiously empty. I had first been encouraged by the integrity and enthusiasm of the young scientists monitoring the stream, which still retained its transparent fascination for me a lifetime later. I could hardly expect it to be unchanged, crayfish notwithstanding. Then, too, so many wild flowers had gone: my sister and I used to gather marsh orchids and ragged robin from the water meadows, when these plants were so profuse that the boggy fields were coloured red with them. I could see that the young biologists did not really believe me when I told them about it. ‘Rose-tinted memory,’ I imagine them thinking, although it was as true as my recollection of the crayfish. My sister was tiny and her bunch of flowers was enormous. Nowadays, we would be horrified by the thought of picking such recherché glories, but it was not the thoughtless picking that prevented their survival – these plants had been thriving on the water meadows for generations. Changes in drainage and the addition of artificial fertilisers to increase yields are more likely culprits. How, I wondered, can you properly convey such loss. When I see those rich leas in my mind’s eye they provide more vivid and solid memories than those of my own father.

Ambivalent feelings did not stop me from further exploration of the Lambourn Valley: I wanted to know the worst. I followed the minor road that runs alongside the stream north-westwards towards Lambourn town, through the villages of Welford and Great Shefford. Now the whole valley had been tastefully prettified. The original cottages were built of cob, or brick and flint, both humble materials that did not have to travel far. The chalk country offered no natural tiles for roofing, so thatch, much like that on our Primrose Cottage, was still a common sight. The river is dwindling. It is easy to follow its course, as lines of willows track it faithfully at the bottom of the valley, their roots nakedly plunging into pools and rills. But somewhere north-west of Great Shefford the streambed seems to have run dry. Maybe it flowed in the winter, and disappeared in the warmer months: there were still trails of flints that marked its course. In Lambourn itself I saw the channel where it was supposed to run through the town, but the stream seemed to have deserted its name-giver. The water table must have fallen to the point where the upper part of the famous chalk stream had run dry. It reappeared downstream where the water table reached the surface, and by the time it reached Boxford the Lambourn was approaching its old self. What was happening now in Berkshire had probably happened some years ago in Hertfordshire to the River Gade, from which a great trout had been snatched a few months after my first birthday. Extraction of the chalk aquifer for too many thirsty throats caused diminution of both rivers. People like to drink chalk water because it has been cleaned and purified by its passage through the white limestone rock: it tastes good. Loss of animals and plants is the cost of tap water ad libitum.

The Lambourn taught my sister and me to swim. The Piscatorial Society ‘beat’ on the river extended south of Boxford to its lower reaches at the village of Bagnor, very close to Newbury. An old mill house interrupted the smooth passage of the stream and below that disused building a mill pool was fed by a cascade that fed through a weir. The river spilled out on the other side into shallows with many a ‘miller’s thumb’. The mill race was fast, but fed into a great deep eddy, so that a floating object would be carried around it in a circle. Along one side of the pool was a submerged ledge. Spring-fed water straight from the chalk was allegedly the coldest in southern England, and every fresh immersion in it provoked a squeal. On perfect summer days it was the equally perfect place for a picnic on the bank, while my father was off with his rod. Under our mother’s eye, we children started with rubber rings around our waists, and jumped from the ledge into the mill race to be carried like flotsam around the eddy to repeat the experience all over again. At some point the rubber rings were shed – and we were swimmers. My sister Kath was two years younger than I was, but she learned to swim first; I can still feel the touch on my feet of the special moss that grew on the mill race and I can still smell the strange exhilarating odour of pure rushing water. Once, after swimming, mother and children went to a scruffy pub on the far side of Bagnor village green. My mother was extravagantly flattered there by an aged charmer, who insisted on buying her a drink – and an expensive one at that. At that time she was at the peak of her womanhood, tall, fit, and often wearing her ‘sundress’, a light flowery confection that exposed her tanned shoulders and flattered her figure. Before this, I had never realised that she was a sexual being, which is probably why this incident has lodged so obstinately amid the general fuzz of my growing up. Afterwards, she giggled and referred to her admirer as an old fool.

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.