Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

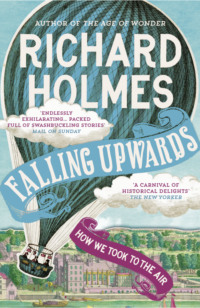

Kitabı oku: «Falling Upwards: How We Took to the Air», sayfa 3

8

In 1785 Tiberius Cavallo, a Fellow of the Royal Society, put together the first British study of ballooning. His A Treatise on the History and Practice of Aerostation studiously adopted the French scientific term for ‘lighter-than-air’ flight, but moved far beyond national rivalries. He wanted to consider the phenomenon of flight from both a scientific and a philosophical point of view. He thought that ballooning held out immense possibilities, less as a transport device than as an instrument for studying the upper air and the nature of weather. This distinction between horizontal and vertical travel would have a long subsequent history.

Cavallo was a brilliant Italian physicist who had moved to London at the age of twenty-two, and had already written extensively on magnetism and electrical phenomena. Elected to the Royal Society in 1779, he quickly turned his attention to ballooning. He had some claims to be one of the first to inflate soap bubbles with hydrogen as early as 1782. Although a handsome portrait is held by the National Portrait Gallery in London, he is now largely and unjustly forgotten. Yet his study emerges as the most authoritative early treatise on the subject of ballooning in either English or French. The copy of Cavallo’s book held by the British Library is personally inscribed ‘To Sir Joseph Banks from the Author’, in severe black ink.

Cavallo carefully adopted a considered and even sceptical tone, well calculated to appeal to Banks. Much had been made of Vincenzo Lunardi’s historic first flight in Britain, in September 1784, when he flew from London to Hertfordshire with his pet cat. The newspapers of the day all declared Lunardi a heroic pioneer, a patriot and an animal lover, although the gothic novelist Horace Walpole – author of The Castle of Otranto – roundly criticised him for risking the life of the said cat. But Cavallo noted: ‘Besides the Romantic observations which might be naturally suggested by the Prospect seen from that elevated situation, and by the agreeable calm he felt after the fatigue, the anxiety, and the accomplishment of his Experiment, Mr Lunardi seems to have made no particular philosophical observation, or such as may either tend to improve the subject of aerostation, or to throw light on any operation in Nature.’23 fn7

Cavallo analysed and dismissed most claims to navigate balloons, except by the use of different air currents at different altitudes.24 He emphasised the aeronaut’s vulnerability to unpredictable atmospheric phenomena such as down-drafts, lightning strikes and ice formation. He deliberately included the first alarming account of a French balloon caught in a thunderstorm, during an ascent from Saint-Cloud in July 1784, and dragged helplessly upwards by a thermal:

Three minutes after ascending, the balloon was lost in the clouds, and the aerial voyagers lost sight of the earth, being involved in dense vapour. Here an unusual agitation of the air, somewhat like a whirlwind, in a moment turned the machine three times from the right to the left. The violent shocks, which they suffered prevented their using any of the means proposed for the direction of the balloon, and they even tore away the silk stuff of which the helm was made. Never, said they, a more dreadful scene presented itself to any eye, than that in which they were involved. An unbounded ocean of shapeless clouds rolled one upon another beneath, and seemed to forbid their return to earth, which was still invisible. The agitation of the balloon became greater every moment … 25

Yet for all this, Cavallo was a passionate balloon enthusiast. He recorded and analysed all the significant flights, both French and English, made from Montgolfier’s first balloon at Annonay in June 1783, to Blanchard and Jeffries’s crossing of the Channel in January 1785. He distinguished carefully between hot-air and hydrogen balloons, and their quite different flight characteristics. He looked in detail at methods of preparing hydrogen gas, noting that Joseph Priestley had come up with one that used steam rather than sulphuric acid. He also examined the different ways of constructing balloon canopies from rubber (‘cauchou’), waxed silk, varnished linen and taffeta.

In a longer perspective, he stressed the astonishing speed of aerial travel over the ground – ‘often between 40 and 50 miles per hour’ – combined with its incredible ‘stillness and tranquillity’ in most normal conditions.26 This he thought must eventually revolutionise our fundamental ideas of transport and communications, even if the moment had not yet arrived. But he was less impressed by the horizontal potential of ballooning than by its vertical one. The essence of flight lay in attaining an utterly new dimension: altitude.

He pointed out that in achieving altitudes of over two miles, balloons opened a whole new perspective on mankind’s observations of the earth beneath. Man’s growing impact on the surface of the planet for the first time became visible. As did the vast tracts of the earth – mountains, forests, deserts – yet to be traversed or discovered. Above all he stressed that the full potential of flight had not yet been remotely explored. The situation has perhaps some analogies with the space exploration programme, in the years following the Apollo missions.

Cavallo considered the whole range of possible balloon applications. But he finally and presciently championed its relevance to the infant science of meteorology:

The philosophical uses to which these machines may be subservient are numerous indeed; and it may be sufficient to say, that hardly anything of what passes in the atmosphere is known with precision, and that principally for want of a method of ascending into the atmosphere. The formation of rain, of thunderstorms, of vapours, hail, snow and meteors in general, require to be attentively examined and ascertained.

The action of the barometer, the refraction and temperature of air in various regions, the descent of bodies, the propagation of sound etc are subjects which all require a long series of observations and experiments, the performance of which could never have been properly expected, before the discovery of these machines. We may therefore conclude with a wish that the learned, and the encouragers of useful knowledge, may unanimously concur in endeavouring to promote the subject of aerostation, and to render it useful as possible to mankind. 27

Cavallo’s work was both a challenge and an intellectual landmark in the early history of ballooning. He was largely responsible for the historic first article on ‘Aerostation’, which appeared in the Encyclopaedia Britannica, with notable illustrations, in 1797. This was a signal date. From then on, flight was officially established as a new branch of scientific knowledge, rather than an old backwater of mythology.

9

Yet there always remains the most enduring early dream or fantasy of flying, which is a metaphysical one. The ultimate purpose is to fly as high as possible, and then look back upon the earth and see mankind for what it really is. This idea has persisted since the beginning, and still continues, sometimes in a satirical form, and sometimes in a visionary one.

The seventeenth-century French dramatist Cyrano de Bergerac (a fearless duellist and also an intellectual provocateur) convincingly reported a secret flight to the moon, undertaken sometime before his death in 1655. It appeared in his posthumously published work Histoire comique des états et empires de la Lune (Comical History of the States and Empires of the Moon). Cyrano’s flight is powered by glass cluster balloons, filled with dew and drawn skyward as the droplets are heated by the sun and evaporate: ‘I planted myself in the middle of a great many Glasses full of Dew, tied fast about me, upon which the Sun so violently darted his Rays, that the Heat, which attracted them, as it does the thickest Clouds, carried me up so high, that at length I found myself above the middle Region of the Air. But seeing that Attraction hurried me up with so much rapidity that instead of drawing near the Moon, as I intended, she seem’d to me to be more distant than at my first setting out …’

After an initial power failure and crash-landing, the final approach, made with the additional aid of gunpowder and a lunar force-field, is memorably disorientating: ‘When according to the calculations I had made, I had travelled much more than three-quarters of the way between earth and moon, I suddenly started falling with my feet uppermost, even though I had not performed a somersault … The earth now appeared to me as nothing but a great plate of gold overhead.’

When Cyrano eventually lands, he is captured and cross-questioned by various lunar inhabitants. One, more kindly than the others, remarks: ‘Well, my son, you are finally paying the penalty for all the failings of your Earth world.’28 Presented before the Lunar Court, he narrowly escapes being condemned to death for impiety. He has maintained the ridiculous notion that ‘our earth was not merely a moon, but also an inhabited world’. He returns in sober mood, crash-landing near a volcano in Italy.29

Some three hundred years later, on 24 December 1968, the Apollo 8 spacecraft came round from the dark side of the moon. The astronaut Bill Anders later recalled: ‘When I looked up and saw the earth coming up on this very stark, beat-up lunar horizon, an earth that was the only colour that we could see, a very fragile-looking earth, a very delicate-looking earth, I was immediately almost overcome by the thought that here we came all this way to the moon, and yet the most significant thing we’re seeing is our own planet, the earth.’

The trip produced one of the most famous colour photographs ever taken. It has become universally known as ‘Earthrise’. The small, beautiful planet earth is sliding above the bleakness of the cratered moon surface, and hanging against the blackness of outer space. From this vision arose the whole modern concept of planet earth as the ‘small blue dot’ of life, amid a dark and mysterious universe.30

The dream of flight is to see the world differently.

2

Fiery Prospects

1

Just like space flight, early balloon flight offered military as well as metaphysical prospects. Cavallo’s dream of scientific ballooning was soon displaced by prospects of a more warlike kind. Benjamin Franklin had warned Sir Joseph Banks of this possibility, and such signs of the times were recognised by many contemporaries, including Banks’s clever younger sister, Sophia. She had begun to make a collection of balloon memorabilia, which she stuck into an enormous red-leather folio scrapbook especially purchased for the purpose. It would eventually run to over a hundred items.1 One of her earliest specimens was a British cartoon, dated 16 December 1784, entitled ‘The Battle of the Balloons’.

This shows four balloons, two flying the French fleur de lys and two the British Union Jack, manoeuvring for aerial combat. Their crews are armed with muskets, but also, more menacingly, with broadside cannons. Their muzzles point through portholes cut in the balloon wickerwork.2 Here the balloon is already conceived of as a weapon of war, comparable to the navy’s ships of the line.

Sophia also had an eye for many of the more eccentric examples of balloon propaganda. One set of this type was ‘Mr Ensler’s Wonderful Air Figures’, in which balloons were constructed in various animal and mythological shapes, such as the ‘Flying Horse Pegasus’. Some of these figures were intended to be provocative, like the giant ‘Nymphe coiffée en ballon et habillée à la Polonaise’. The Frenchified style of this description suggests sexual mockery. Then there was the bluffly patriotic ‘Mr Prossor’s Aerial Colossus’, showing an enormous ‘Sir John Falstaff’ floating defensively above the Dover cliffs.3 Such inventions were probably pure design fantasies, or at the most models, never actually manufactured full-size. But they suggest how balloons would become powerful forms of imaginative propaganda later, in the nineteenth century.fn8

2

The first actual military balloon regiment, as Franklin had prophesied, was indeed French. The Corps d’Aérostiers was founded at the château of Meudon outside Paris on 29 March 1794. Less than three months later, on 26 June, the French army first made use of a military observation balloon at the Battle of Fleurus, against an Austrian army, and again a few weeks later at the Battle of Liège (where it was witnessed by the galloping Major Money). The balloon, manned on both occasions by a daring young officer, Captain Charles Coutelle, provided vital information prior to successful cavalry charges, and both battles were won by the fledgling French Revolutionary army.

The balloon school at Meudon was immediately expanded, and Coutelle showered with medals and appointed its commanding officer. He rapidly drew various lessons about military aerostation. First, that it was difficult to inflate a balloon with hydrogen on the battlefield. (Lavoisier was immediately coopted to invent a simpler method of generating hydrogen.) Second, that it was extremely hazardous to launch a tethered balloon if anything more than a light breeze was blowing. Held, kite-like and unnaturally on its cable against the force of the wind (instead of moving tranquilly within it), the balloon canopy would often thrash about and sometimes tear. Moreover, instead of gaining height it would fly horizontally and low. Above all, the basket would become highly unstable as an observation platform. Coutelle also remarked that it was not always easy to transmit really accurate and continuous observations from an airborne basket to a ground controller. Signal flags, scrawled messages or maps were rarely adequate. In most cases the aeronaut had simply to be winched back down, so he could deliver his appreciation verbally to a commander, in person and on the ground. Interestingly, it proved very difficult to get any commander to go up to see for himself.

But overall Coutelle believed that balloons promised considerable military value. He argued that, under the right conditions, a balloon would give an immense intelligence advantage to an army on the move, whether defending or attacking. It provided a wholly new tactical weapon, a ‘spy in the sky’ which could supply vital warning of troop build-ups and defensive positions, as well as preparations for attack or (equally vital) for retreat. Such observations could give a commander a decisive initiative in the field.

More subtly, a balloon was also an extraordinary psychological weapon. Because of its height, every individual soldier could see an enemy balloon hovering above a battlefield. By a trick of perception, this gave the impression to every soldier that he, in turn, could always be seen by the balloon. So everything he did was being observed by the enemy. There was no hiding place, no escape. The very presence of such a balloon above a battlefield was peculiarly menacing and demoralising. The enemy might certainly read an enemy soldier’s intentions, and even seem to read his thoughts. This alone made it a powerful military instrument. An Austrian officer was reported, after his army’s defeat at Fleurus, as murmuring, ‘One would have supposed the French General’s eyes were in our camp.’ His troops complained more angrily, ‘How can we fight against these damned Republicans, who remain out of reach but see all that passes beneath.’4

There was one unforeseen consequence of this. The French balloons quickly came to be universally hated by the opposing allied armies. As a result, they immediately attracted intense and sustained enemy fire, with every weapon that could be mustered, from pistols and muskets to cannon and grapeshot, directed at the observers’ basket. This, concluded Coutelle, made the military aeronaut’s position both peculiarly perilous and peculiarly glamorous.

The Corps d’Aérostiers eventually fielded four balloons, complete with special hangar tents, winches, mobile gas-generating vessels (designed by Lavoisier) and observation equipment. Coutelle would write a racy history of the Meudon balloon school, with modest emphasis on both the tactical and the amorous successes of the French military aeronauts. Wilfrid de Fonvielle later observed: ‘The favour of the ladies followed the balloonists wherever they went, which was not an unmixed blessing, and seems in the end to have contributed to the suppression of the corps.’5

With the declaration of war against Britain in 1794, many plays, poems and cartoons imagined an airborne invasion – both French and English – across the Channel. The Anti-Jacobin published invasion-scare cartoons featuring the French guillotine set up in Mayfair, and also extracts from a play purportedly running at the Théâtre des Variétés in Paris: La Descente en Angleterre: Prophétie en deux actes.6 There were some remarkable fantasy drawings of entire French cavalry squadrons mounted on large, circular platforms sustained by enormous Montgolfiers, sailing over the white cliffs of Dover. Nevertheless, the much-feared aerial invasion of England by Napoleon’s army never quite materialised.

In 1797 Napoleon triumphantly took the Corps d’Aérostiers with him to Egypt, counting on the very sight of balloons to put terror into the heart of his Arab enemies, as Hannibal’s elephants had once done in Italy. On 1 August 1798 Coutelle was preparing to unload all his gear outside Alexandria from the French fleet’s mooring at Aboukir Bay when Nelson sailed in at dusk. At the ensuing three-day Battle of the Nile, half of Napoleon’s ships were destroyed, and with them the entire Corps d’Aérostiers. The surviving aeronauts stayed on in Alexandria as technical advisers, like melancholy cavalry officers deprived of their horses. On his return home Napoleon disbanded the corps and the school at Meudon.

Nevertheless, rumours of a French airborne army invading Britain continued to be cultivated, and remained a powerful element in both French and British propaganda long into the nineteenth century. It was the aerial dream turned nightmare.

3

Civilian balloons and a different kind of competitive showmanship reappeared in France at the time of the Peace of Amiens in 1802. They were promoted by André-Jacques Garnerin (1770–1825), who launched his career by performing a spectacularly dangerous first parachute drop from a balloon over Paris’s Parc Monceau in 1797, when he was twenty-seven. As a young man, Garnerin had fought in the French Revolutionary armies, but he had been captured and incarcerated in the Hungarian castle of Buda for three desperate years. He spent his time there designing imaginary balloons to lift him out of the prison courtyard, or parachutes with which he could leap from the castle battlements.7 Finally released and returned to Paris, he turned his ballooning escape-fantasies into a full-time profession, and became head of the first of the famous French ‘balloon families’ (a role later inherited by the Godards).

Garnerin pioneered a new kind of balloon event: not merely the conventional single ascent, but a whole series of acrobatic displays, parachute drops and night-flights with fireworks. To add to the excitement, his dashing young wife Jeanne-Geneviève made the first recorded parachute jump by a woman in 1799. These shows attracted enormous crowds, and soon the Garnerins became famous throughout European capitals. Garnerin had numerous posters made of their flights, often showing him in heroic, eagle-like profile. Napoleon himself began to see that the balloon had a potential propaganda value even greater than the military one.8

The Peace of Amiens was barely signed when Garnerin daringly took his balloon show and parachute drops to London. His reception was surprisingly friendly, perhaps because he was joined not only by Jeanne-Geneviève, but also by his pretty niece Lisa. Garnerin’s first London ascent, from Chelsea Gardens on 28 June 1802, attracted a huge audience: ‘Not only were Chelsea Gardens crowded, and the river covered with boats, but even the great road from Buckingham Gate was absolutely impassable, and the carriages formed an unbroken chain from the turnpike to Ranelagh Gate.’9

Fearlessly launching in a near-gale, Garnerin flew along the line of the Thames, from the West End to the East End, directly over the City, and then out north-eastwards over the Essex marshes. He was effectively seen by half the population of London. Forty-five minutes later he crash-landed in Colchester, but came back the same day in a coach, gallantly announcing that his balloon had been torn to pieces – ‘we ourselves are all-over bruises’ – but that he would fly again within the week. Indeed, he next ascended from the old Lord’s cricket ground (on the site of the present-day Dorset Square) on 5 July. Advertising his flights with sensational engravings, Garnerin popularised night-ballooning and parachuting in England, and also the dangerous attitude that ‘the balloon show must go on’ whatever the weather.

The following year, 1803, Garnerin published Three Aerial Voyages, describing his London flights and including an amusing account, evidently intended for English readers, supposedly written by his wife’s cat: ‘Brought up under the care of Madame Garnerin, I may be said to have been nursed in the very bosom of aerostation, and to have breathed nothing but the pure air of oxygenated gas since the first moment of my birth. Hearing of my mistress’s intended ascension, I determined to share the danger …’10

Scientific ballooning was not entirely forgotten in France. In August 1804 the mathematician Jean-Baptiste Biot and the chemist Joseph Gay-Lussac made a high-altitude scientific ascent, in the one war balloon Coutelle had succeeded in bringing back from Cairo to Paris. They tested the composition of the air in the upper atmosphere, and the strength of the magnetic field, but found no significant alteration from ground level in either. Biot passed out during the descent, so Gay-Lussac went up again alone in September, climbing to 22,912 feet, a new altitude record which would stand for over half a century. Here, in the tradition of Dr Alexander Charles, along with his instrument readings he calmly recorded his breathlessness, fast respiration and pulse, inability to swallow and other symptoms, and concluded that he was very close to the limit of the breathable atmosphere. In the historical section of his classic book Through the Air (1873), the great American aeronaut John Wise later reflected on the courage of these early scientific ascents into the absolute unknown: ‘It is impossible not to admire the intrepid coolness with which they conducted these experiments … with the same composure and precision as if they had been quietly seated in their scientific cabinet in Paris.’ Wise also raised the prophetic possibility of using such high-altitude balloons unmanned for weather observations: ‘Balloons carrying “register” thermometers and barometers might be capable of ascending alone to altitudes between eight and twelve miles.’ But such experiments would have to wait for a time of international scientific cooperation, ‘when nations shall at last become satisfied with cultivating the arts of peace, instead of sanguinary, destructive and fruitless wars’.11

Indeed, it was the celebration balloon, used for propaganda and patriotic rather than scientific purposes, that most readily held the public’s attention in France. In December 1804 Napoleon commissioned Garnerin to construct and launch a massive, decorated but unmanned balloon to celebrate his coronation as emperor in Paris. It was festooned with silk drapes, flags and banners, and carried an enormous golden imperial crown suspended from its hoop on golden chains. Having been successfully launched above Notre Dame during the coronation ceremony, this fantastic contraption flew southwards right across France, and amazingly crossed the Alps during the night. The following day it was spotted symbolically descending upon Rome, the imperial city, a triumph for Garnerin’s craftsmanship.12

The huge balloon veered towards St Peter’s and the Vatican Palace, then swooped down low across the Forum. But here the symbolic triumph was turned into a propaganda disaster. The enormous golden crown became hooked on the top of an ancient Roman tomb and broke off, leaving the balloon to disappear, with its banners flapping, over the Pontine Marshes. By unbelievable coincidence, or thoroughly appropriate bad luck (you can never tell with balloons), the tomb upon which Garnerin’s prophetic balloon had deposited Napoleon’s golden crown was that of the infamous tyrant and murderous pervert, the Emperor Nero. Napoleon’s name was hooped like a deck-quoit over Nero’s.fn9 Once this ill-starred news was efficiently relayed back to Paris by Napoleon’s diplomatic service, Garnerin and his balloons began to fall out of imperial favour.14

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.