Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

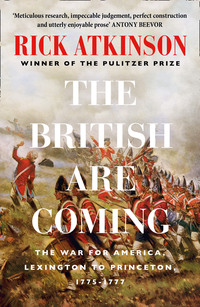

Kitabı oku: «The British Are Coming»

To Jane, for forty years

Contents

1 TITLE PAGE

2 DEDICATION

3 EPIGRAPH

4 LIST OF MAPS

5 MAP LEGEND

6 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

7 PROLOGUE, England, June 1773–March 1775

8 1. Inspecting the Fleet

9 2. Avenging the Tea

10 3. Preparing for War

11 Part One

12 1. GOD HIMSELF OUR CAPTAIN

13 Boston, March 6–April 17, 1775

14 2. MEN CAME DOWN FROM THE CLOUDS

15 Lexington and Concord, April 18–19, 1775

16 3. I WISH THIS CURSED PLACE WAS BURNED

17 Boston and Charlestown, May–June 1775

18 4. WHAT SHALL WE SAY OF HUMAN NATURE?

19 Cambridge Camp, July–October 1775

20 5. I SHALL TRY TO RETARD THE EVIL HOUR

21 Into Canada, October–November 1775

22 6. AMERICA IS AN UGLY JOB

23 London, October–November 1775

24 7. THEY FOUGHT, BLED, AND DIED LIKE ENGLISHMEN

25 Norfolk, Virginia, December 1775

26 8. THE PATHS OF GLORY

27 Quebec, December 3, 1775–January 1, 1776

28 Part Two

29 9. THE WAYS OF HEAVEN ARE DARK AND INTRICATE

30 Boston, January–February 1776

31 10. THE WHIPPING SNAKE

32 Cork, Ireland, and Moore’s Creek, North Carolina, January–March 1776

33 11. CITY OF OUR SOLEMNITIES

34 Boston, March 1776

35 12. A STRANGE REVERSE OF FORTUNE

36 Quebec, April–June 1776

37 13. SURROUNDED BY ENEMIES, OPEN AND CONCEALED

38 New York, June 1776

39 14. A DOG IN A DANCING SCHOOL

40 Charleston, South Carolina, June 1776

41 15. A FIGHT AMONG WOLVES

42 New York, July–August 1776

43 16. A SENTIMENTAL MANNER OF MAKING WAR

44 New York, September 1776

45 Part Three

46 17. MASTER OF THE LAKES

47 Lake Champlain, October 1776

48 18. THE RETROGRADE MOTION OF THINGS

49 New York, October–November 1776

50 19. A QUAKER IN PARIS

51 France, November–December 1776

52 20. FIRE-AND-SWORD MEN

53 New Jersey, December 1776

54 21. THE SMILES OF PROVIDENCE

55 Trenton, December 24–26, 1776

56 22. THE DAY IS OUR OWN

57 Trenton and Princeton, January 1777

58 EPILOGUE, England and America, 1777

59 Photographs

60 AUTHOR’S NOTE

61 NOTES

62 SOURCES

63 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

64 INDEX

65 ALSO BY RICK ATKINSON

66 ABOUT THE AUTHOR

67 COPYRIGHT

68 ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

The hour is fast approaching on which the honor and success of this army and the safety of our bleeding country depend. Remember, officers and soldiers, that you are freemen, fighting for the blessings of liberty.

—George Washington, General Orders, August 23, 1776

Maps

1. The British Empire, 1775

2. The North American Theater, April 1775–January 1777

3. Boston, Spring 1775

4. March to Concord, April 18–19, 1775

5. British Retreat from Concord, April 19, 1775

6. Bunker Hill, June 17, 1775

7. Invasion of Canada, September–November 1775

8. Great Bridge and the Burning of Norfolk, December 1775–January 1776

9. Disaster at Quebec, December 31, 1775

10. Siege of Boston, Winter 1775–1776

11. Skirmish at Moore’s Creek Bridge, February 27, 1776

12. Retreat from Canada, May–June 1776

13. Greater New York, Summer 1776

14. New York City, Summer 1776

15. Battle of Sullivan’s Island, June 28, 1776

16. Battle of Long Island, August 22–30, 1776

17. Battle of Kip’s Bay and Harlem Heights, September 15–16, 1776

18. Battle for Lake Champlain, October 1776

19. Battle for Westchester County, October 1776

20. Attacks on Fort Washington and Fort Lee, November 16–20, 1776

21. Franklin in France, December 1776

22. Retreat Across New Jersey, November–December 1776

23. First Battle of Trenton, December 25–26, 1776

24. Second Battle of Trenton and Battle of Princeton, January 2–3, 1777

Illustrations

FIRST INSERT

1. Johan Joseph Zoffany, George III, oil on canvas, 1771. (Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2018)

2. John Clevely, George III Reviewing the Fleet at Spithead, 22 June 1773, watercolor, 1773. (© National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London)

3. John Russell, Frederick North, 2nd Earl of Guilford, oil on canvas, c. 1765-68. (Private collection/Bridgeman Images)

4. Nathaniel Hone I, William Legge (1731–1801), Second Earl of Dartmouth, oil on canvas, 1777. (Courtesy of Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College. Gift of Earle W. Newton, P.960.100)

5. Jan Josef Horemans II, Tea Time, oil on canvas, second half of eighteenth century.

6. John Collet, Scene in a London Street, oil on canvas, 1770. (Courtesy Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection)

7. Christian Schussele, Franklin before the Lords’ Council, Whitehall Chapel, London, 1774, engraved by Robert Whitechurch, c. 1859. (Courtesy Library of Congress)

8. Rudolf Ackermann et al, House of Commons from Microcosm of London, 1808–10. (Courtesy British Library)

9. Johan Joseph Zoffany, George III, Queen Charlotte, and Their Six Eldest Children, oil on canvas, 1770. (Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2018)

10. Gold State Coach, gilded and painted wood, leather, 1762. (Photograph, Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2018)

11. Thomas Bowles, A View of St. James’s Palace Pall Mall, engraving, 1771. (Courtesy Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection)

12. John Singleton Copley, General Thomas Gage, oil on canvas, c. 1768. (Courtesy Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection)

13. John Singleton Copley, Mrs. Thomas Gage, oil on canvas, 1771. (Putnam Foundation, Timken Museum of Art)

14. John Trumbull, Benjamin Franklin, oil on wood, 1778. (Courtesy Yale University Art Gallery)

15. John Singleton Copley, Paul Revere, oil on canvas, 1768. (Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

16. John Singleton Copley, Joseph Warren, (unfinished), oil on canvas, c. 1772. (Courtesy National Park Service, Adams National Historical Park)

17. Thomas Sully, after Charles Willson Peale. Major General Artemas Ward, oil on canvas, c. 1830-40. (Collection of the Massachusetts Historical Society)

18. Dominique C. Fabronius, Maj. Gen. Israel Putnam. “He dared to lead where any dared to follow,” lithograph, c. 1864. (Courtesy Library of Congress)

19. John Stark, date unknown. (Courtesy Print Collection, New York Public Library)

20. Gilbert Stuart, Hugh Percy, Second Duke of Northumberland, oil on canvas, c. 1788. (Courtesy High Museum of Art, Atlanta)

21. Amos Doolittle, A View of the Town of Concord, plate II, engraving, Dec. 1775, reprint by Charles E. Goodspeed, 1903.

22. Henry A. Thomas, The Battle at Bunker’s Hill, lithograph, c. 1875. (Courtesy Library of Congress)

23. Charles Willson Peale, George Washington, oil on canvas, 1776. (Courtesy Brooklyn Museum, Dick S. Ramsay Fund)

24. Charles Peale Polk, copy after Charles Willson Peale, Henry Knox, oil on canvas, after 1783. (Courtesy National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution)

25. Washington’s Headquarters, Cambridge, date unknown. (Courtesy Print Collection, New York Public Library)

26. Nathaniel Hone, George Sackville Germain, 1st Viscount Sackville, oval portrait, 1760. (© National Portrait Gallery, London)

27. Joshua Reynolds, John Murray, 4th Earl of Dunmore, oil on canvas, 1765. (National Galleries Scotland)

28. H. B. Hall after John Trumbull, Benedict Arnold, engraving, published after 1879. (Courtesy National Archives, 532921)

29. Ph. Schuyler, date unknown. (Courtesy Print Collection, New York Public Library)

30. Alonzo Chappel, Richd. Montgomery, engraving by George R. Hall, 1881. (Courtesy Print Collection, New York Public Library)

31. Eyving H. de Dirkine Holmfield, Guy Carleton, oil on canvas, c. 1895. (© Château Ramezay, Historic Site and Museum of Montréal)

32. Quebec in 1775, date unknown. (Courtesy Print Collection, New York Public Library)

33. John Trumbull, The Death of General Montgomery in the Attack on Quebec, December 31, 1775, oil on canvas, 1786. (Courtesy Yale University Art Gallery)

34. Château Ramezay, artist and date unknown. (© Château Ramezay, Historic Site and Museum of Montréal)

35. James Peale, Horatio Gates, oil on canvas, copy after Charles Willson Peale, 1782. (Courtesy National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution)

36. Gen. Sir William Howe, date unknown. (Courtesy Print Collection, New York Public Library)

37. John Burgoyne, date unknown. (Courtesy National Archives, 532920)

38. Michael Angelo Wageman, Genl. Howe Evacuating Boston, engraving by John Godfrey, 1861. (Courtesy Anne S. K. Brown Military Collection, Brown University Library)

SECOND INSERT

39. John Singleton Copley, Admiral Richard Howe, 1st Earl Howe, oil on canvas, 1794. (© National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London, Caird Collection)

40. Archibald Robertson, View of the Narrows between Long Island & Staten Island with our fleet at anchor, etc., ink and wash on paper, 1776. (Courtesy New York Public Library, Spencer Collection)

41. Allan Ramsay, Flora Macdonald, oil on canvas, 1749. (Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archeology, University of Oxford)

42. Sir Henry Clinton, date unknown. (Courtesy Print Collection, New York Public Library)

43. Gen. Lord Cornwallis, date unknown. (Courtesy Print Collection, New York Public Library)

44. Major Gen.l Charles Lee, date unknown. (Courtesy Print Collection, New York Public Library)

45. Charles Willson Peale, William Moultrie, oil on canvas, 1782. (National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution. Transfer from the National Gallery of Art, gift of the A. W. Mellon Educational and Charitable Trust, 1942)

46. Slave auction notice, 1760. (“The Atlantic Slave Trade and Slave Life in the Americas,” website for Virginia Foundation for the Humanities. Original source: Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC-USZ62-10293)

47. Thomas Leitch, A view of Charles-Town, the capital of South Carolina, engraved by Samuel Smith, 1776. (Courtesy Library of Congress)

48. Nicholas Pocock, A View of the Attack Made by the British Fleet under the Command of Sir Peter Parker, etc., oil on canvas, 1783. (South Caroliniana Library, University of South Carolina)

49. Charles Édouard Armand-Dumaresq, The Declaration of Independence of the United States of America, July 4, 1776, oil on canvas, c. 1873.

50. Laurent Dabos, Thomas Paine, oil on canvas, c. 1792. (Courtesy National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution)

51. James Wallace and Dominic Serres, The Phoenix and the Rose engaged by the enemy’s fire ships and galleys on the 16 Augst. 1776, engraving, 1778. (Courtesy Print Collection, New York Public Library)

52. Alonzo Chappel, Battle of Long Island, oil on canvas, 1858. (Brooklyn Historical Society)

53. Bushnell’s American Turtle, engraving, 1881. (Courtesy Library of Congress)

54. Thomas Mitchell, Forcing a passage of the Hudson River, 9 October 1776, oil on canvas, date unknown, copy of original by Dominic Serres the Elder. (© National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London)

55. Robert Cleveley, The British landing at Kip’s Bay, New York Island, 15 September 1776, pen and ink, black and watercolor, 1777. (© National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London)

56. The Battle of Harlem Heights, September 16, 1776, date unknown. (Courtesy Print Collection, New York Public Library)

57. Charles Willson Peale, Nathanael Greene, watercolor on ivory, 1778. (Courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art, bequest of Charles Allen Munn, 1924)

58. Luther G. Hayward, Colonel Roger Morris’ House, 1854. (© The Morris-Jumel Mansion, gift of Lydia Malbin)

59. John Trumbull, General John Glover, graphite, 1794. (Courtesy Yale University Art Gallery)

60. William Glanville Evelyn, frontispiece portrait, artist unknown, 1775. (From G. D. Scull, ed., Memoirs and Letters of Captain W. Glanville Evelyn, 1879)

61. Thomas Davies, The landing of the British forces in the Jerseys on the 20th of November 1776, etc., watercolor, 1776. (Courtesy Print Collection, New York Public Library)

62. Jean-Marc Nattier, Portrait of Pierre-Augustin Caron de Beaumarchais, oil on canvas, 1755. (ART Collection/ Alamy Stock Photo)

63. Jean-Baptiste Raguenet, A View of Paris from the Pont Neuf, oil on canvas, 1763. (Courtesy Getty Center, Open Content Program, J. Paul Getty Museum)

64. Silas Deane, date unknown. (Courtesy Print Collection, New York Public Library)

65. Joseph Duplessis, Portrait of Louis XVI, King of France and Navarre, oil on canvas, c. 1776-78.

66. Antoine-François Callet, Charles Gravier Comte de Vergennes, engraving by Vincenzio Vangelisti, c. 1774–89. (Courtesy Library of Congress)

67. Charles Willson Peale, Dr. Benjamin Rush, oil on canvas, 1783–86. (Winterthur Museum, gift of Mrs. Julia B. Henry)

68. Thomas Sully, The Passage of the Delaware, oil on canvas, 1819. (Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; gift of the Owners of the Old Boston Museum)

69. John Sullivan, wood engraving, date unknown. (Courtesy Print Collection, New York Public Library)

70. Brig. Gen. Joseph Reed, date unknown. (Courtesy Print Collection, New York Public Library)

71. John Trumbull, The Capture of the Hessians at Trenton, December 26, 1776, oil on canvas, 1786–1828. (Courtesy Yale University Art Gallery)

72. “Plan of Princeton, Dec. 31, 1776,” manuscript map, pen and ink. (Courtesy Library of Congress)

73. Major Gen. James Grant, Colonel of the 55th Foot, date unknown. (Courtesy Print Collection, New York Public Library)

74. John Trumbull, Gen. Hugh Mercer, copy of an original pencil sketch created in 1791. (Courtesy Print Collection, New York Public Library)

75. John Trumbull, Death of General Mercer at the Battle of Princeton, sketch for The Battle of Princeton, pen and ink wash, 1786. (Courtesy Battle of Princeton Prints Collection, GC047, Graphic Arts Collection, Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, Princeton University Library)

76. James Peale, The Battle of Princeton, oil on canvas, c. 1782. (Princeton University Art Museum/Art Resource, NY)

Prologue

ENGLAND, JUNE 1773–MARCH 1775

Inspecting the Fleet

At three-thirty a.m. on June 22, 1773, fifteen minutes before sunrise, a royal chaise pulled by four matched horses burst from the gates of Kew Palace, escorted by cavalry outriders in scarlet coats. South they rode, skirting the Thames valley west of London before rattling onto the Surrey downs. Pearly light seeped into the landscape, and the brilliant green of an English summer day—the first full day following the solstice—emerged from the fens and fields. Even at this early hour the roads were crowded, for all England knew that a great review was planned at the royal dockyards in Portsmouth, a four-day celebration of the fleet that a decade before had crushed France and Spain in the Seven Years’ War to give rise to the British Empire. An exasperated message to the Admiralty headquarters in London earlier this week had warned of “it being almost impossible to get horses on the road owing to the multitude of people going to Portsmouth.” That throng, according to a newspaper account, included “admirals, captains, and honest Jack Tars in abundance … courtiers and parasites, placemen and pensioners, pimps and prostitutes, gamblers and pickpockets.” Innkeepers on the south coast were said to demand ten guineas a night for a bed.

The king himself, a demon for details, had choreographed this seven-hour journey from Kew, arranging the postilions, footmen, and grooms like chess pieces. He had calculated the distance and duration of each leg along the sixty-three-mile route, writing memoranda in his looping, legible hand, adorned only with a delicate filigree of ink that rose from each final lowercase d—as in “God”—to snake back across the paper like a fly fisherman’s line. Nine relays of horses waited along the route in places called Ripley and Godalming, but none at Lotheby Manor on the Portsmouth road, perhaps because an ancient English custom required that if a monarch visited Lotheby, the lord of the manor was “to present His Majesty with three whores.” Or so the London Chronicle claimed.

Bells pealed in welcome as the cavalcade rolled into Hampshire. Country folk stood before their rude cottages, some in farm frocks and red cloaks, some in their Sunday finery, though it was Tuesday. All strained for a glimpse of the man who sat alone with his thoughts in the chaise: George William Frederick, or, as he had been proclaimed officially upon ascending the throne in 1760, “George III, by the grace of God, king of Great Britain, France, and Ireland, defender of the faith, and so forth.” (The claim to France was a bit of nostalgia dating to the fourteenth century.) Below Petersfield, the crowds thickened, spilling along the chalky ridges above the roadbed, and when George emerged from his carriage for a five-minute pause at Portsdown Hill, five thousand people bayed their approval while he admired the vista of the harbor below and the sapphire anchorage that stretched across to the Isle of Wight.

Half an hour later, a royal salute of twenty-one guns sounded from Portsea Bridge. Just after ten a.m. the White Boys, local burghers dressed entirely in white, cleared a lane for the king’s chaise through the throng at Landport Gate. More salutes greeted him, including a triple discharge from 232 guns on Portsmouth’s ramparts in a mighty cannonade heard sixty miles away. When the jubilant crowd pressed close, soldiers from the 20th Regiment prodded them back with bayonets until George urged caution. “My people,” he said, “will not hurt me.”

Most of his cabinet ministers had traveled from London, along with Privy Council members and a royal household contingent of physicians, surgeons, and apothecaries, who had been advised to bring ample spirits of lavender to calm the jittery. Dense ranks of army and navy officers, along with Portsmouth’s better sort, jammed a public levee at the Governor’s House in hopes of kissing the king’s hand. A prayer that “the fleet may ever prove victorious” was followed by a recitation of “The Wooden Walls of England,” a new, four-stanza tribute to the navy: “Hail, happy isle!… Spread then thy sails where naval glory calls, / Britain’s best bulwarks are her wooden walls.”

Then it was off to see those wooden walls. At one-thirty p.m., draped in a crimson boat cloak adorned with an enormous star of the Order of the Garter, George stepped aboard his ten-oar barge for the three-mile trip to Spithead anchorage. A flotilla trailed in his wake, filled to the gunwales with nobility, gentry, and sea dogs in blue and braid; the procession included the venerable Fubbs—the word was slang for chubby—a yacht named for a favorite mistress of Charles II’s. A gentle June breeze riffled the sea, and in the clear sunshine five hundred vessels large and small could be seen all around: brigs, corvettes, wherries, schooners, frigates, sloops.

Most imposing were twenty ships of the line moored in two facing ranks along five miles of roadstead. Each wore new paint, their bowsprits steeved at a pugnacious tilt of thirty-six degrees above the horizon, their sterns boasting names like Royal Oak, Centaur, Terrible, and Triumph. Some six thousand crewmen crowded their decks, and as the king drew near, fourteen hundred guns opened in another thunderous salute, salvo upon salvo. At last the cannonade stopped, the great gouts of smoke drifted off, and each vessel hoisted its colors, a bright riot of pendants and banners; four hundred flags fluttered from Kent alone. Spectators lined the walls in Portsmouth and along the promenade in adjacent Gosport, where alehouse keepers had erected canvas booths to sell fried sausages and shilling lumps of veal and ham. Now the crowds pressed to the water’s edge, delirious with pride, and their roar carried to the king’s ear, still ringing from all those guns.

As he braced himself in the rocking barge, he looked the part, this king, all silk and fine brocade, “tall and full of dignity,” as one observer recorded, “his countenance florid and good-natured.” At thirty-five, George had the round chin and long nose of his German forebears, with fine white teeth and blue eyes that bulged from their orbits. He had been a sickly baby, not expected to survive infancy; now he incessantly touted “air, moderate exercise, and diet,” and he could often be found on horseback in pursuit of stag or hare. Not for another fifteen years would he be stricken with the first extended symptoms—perhaps caused by porphyria, a hereditary affliction—that included abdominal pain, neuritis, incoherence, paranoia, and delirium. More attacks followed later in his life, along with the madness that wrecked his old age.

Unkind and untrue things often were said of him, such as the claim that he could not read until age eleven; in fact, at a much younger age he could read and write in both English and German. There was no denying that he was an awkwardly shy boy, “silent, modest, and easily abashed,” as a courtier observed. In 1758 a tutor described the prince at twenty, noting traits that would bear more than a passing resemblance to the adult king: “He has rather too much attention to the sins of his neighbor.… He has great command of his passions, and will seldom do wrong except when he mistakes wrong for right.” Still, in the past decade or so he had grown into an admirable man of parts—diligent, dutiful, habitually moderate, peevish but rarely bellicose. Not easily duped, he had what one duchess called “a wonderful way of knowing what is going forward.” He was frugal in an age of excess, pious at a time of impiety. His interests ranged from physics and theology to horticulture and astronomy—he had built the Royal Observatory at Richmond to view the transit of Venus in 1769—and his tastes ran from high to low: Handel, Shakespeare, silly farces that brought his hearty guffaw ringing from the royal box. His sixty-five thousand books would stock the British national library.

Even his idiosyncrasies could be endearing. Until blindness overtook him in the early 1800s, George served as his own secretary, meticulously dating his correspondence with both the day of the month and the precise time, to the very minute. He copied out his own recipes for cough syrup (rosemary, rice, vinegar, brown sugar, all “boiled in silver”) and insecticide (wormwood, vinegar, lime, swine’s fat, quicksilver). He kept critical notes on dramatic actors—“had a formal gravity in his mien, and a piercing eye” or “more manly than elegant, of the middle stature, inclining to corpulency.” He would personally decide which English worthies should get the pairs of kangaroos brought home by an expedition to Australia. Increasingly his conversational style inclined to repetitive exclamation: “What! What! What!” or “Sad accident! Sad accident!” His compulsion for detail drew him into debates on the proper placement of straps on Foot Guards uniforms.

Unlike the two German-born Georges who preceded him—the House of Hanover had been tendered the throne at Westminster in 1714, when Britain was desperate for a Protestant monarch—this George was thoroughly English. “Born and educated in this country,” he proclaimed, “I glory in the name of Britain.” The three requirements of a British king came easily to him: to shun Roman Catholicism, to obey the law, and to acknowledge Parliament, which gave him both an annual income of £800,000 and an army. Under reforms of the last century, he could not rule by edict but, rather, needed the cooperation of his ministers and both houses of Parliament. He saw himself as John Bull, the frock-coated, commonsensical embodiment of this sceptered isle, while acknowledging that “I am apt to despise what I am not accustomed to.”

There was the rub. Unkind things were sometimes said of him, and not all were untrue. George disliked disorder, and he loathed disobedience. He had an inflexible attachment to his own prejudices, with, one biographer later wrote, “the pertinacity that marks little minds of all ranks.” His “unforgiving piety,” in the phrase of a contemporary, caused him to resist political concession and to impute moral deficiencies to his opponents. He bore grudges.

He saw himself as both a moral exemplar and the guardian of British interests—a thankless task, given his belief that he lived in “the wickedest age that ever was seen.” Royal duty required that he help the nation avoid profligacy and error. He was no autocrat, but his was the last word; absent strong, countervailing voices from his ministers, his influence would be paramount, particularly with respect to, say, colonial policy.

His obstinacy derived not only from a mulish disposition but from sincere conviction: the empire, so newly congealed, must not melt away. George had long intended to rule as well as reign, and as captain general of Britain’s armed forces, he took great pride in reciting the capital ships in his navy, in scribbling endless lists of regiments and army generals, in knowing the strong points of Europe’s fortified towns and the soundings of naval ports and how many guns the Royal Artillery deployed in America. He was, after all, defender not only of the faith but of the realm. In recent sittings for portrait painters, he had begun to wear a uniform.

And if his subjects cheered him to the echo, why should they not? Theirs was the greatest, richest empire since Rome. Britain was ascendant, with mighty revolutions—agrarian and industrial—well under way. A majority of all European urban growth in the first half of the century had occurred in England; that proportion was now expanding to nearly three-quarters, with the steam engine patented in 1769 and the spinning jenny a year later. Canals were cut, roads built, highwaymen hanged, coal mined, iron forged. Sheep would double in weight during the century; calf weights tripled. England and Wales now boasted over 140,000 retail shops. A nation of shopkeepers had been born.

War had played no small role. Since the end of the last century, Britain had fought from Flanders and Germany to Iberia and south Asia. Three dynastic, coalition wars against France and her allies, beginning in 1689, ended indecisively. A fourth—the Seven Years’ War—began so badly that the sternest measures had been taken aboard the Monarch in these very waters. Here on March 14, 1757, Admiral John Byng, convicted by court-martial of “failing to do his utmost” during a French attack on Minorca, had been escorted in a howling gale to a quarterdeck sprinkled with sawdust to absorb his blood. Sailors hoisted aboard a coffin already inscribed with his name. Dressed in a light gray coat, white breeches, and a white wig, Byng knelt on a cushion and removed his hat. After a pardonable pause, he dropped a handkerchief from his right hand to signal two ranks of marines with raised muskets. They fired. Voltaire famously observed that he died “pour encourager les autres.”

The others had indeed been encouraged. The nation’s fortunes soon reversed. Triumphant Britain massed firepower in her blue-water fleet and organized enough maritime mobility to transport assault troops vast distances, capturing strongholds from Quebec and Havana to Manila in what would also be called the Great War for the Empire. British forces routed the French in the Caribbean, Africa, India, and especially North America, with help from American colonists. “Our bells are worn threadbare with ringing for victories,” one happy Briton reported.

Spoils under the Treaty of Paris in 1763 were among the greatest ever won by force of arms. From France, Britain took Canada and half a billion fertile acres between the Appalachian Mountains and the Mississippi River, plus several rich islands in the West Indies and other prizes. Spain ceded Florida and the Gulf Coast. Britain emerged with the most powerful navy in history and the world’s largest merchant fleet, some eight thousand sail. The royal dockyards, of which Portsmouth was preeminent, had become both the nation’s largest employer and its most sophisticated industrial enterprise.