Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

Kitabı oku: «The Prow Beast»

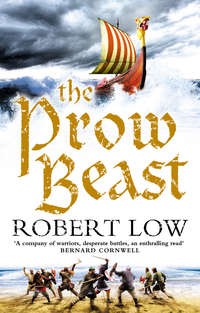

The Prow Beast

Robert Low

HarperCollinsPublishers

HarperCollinsPublishers

To my daughter Monique – all the treasure this father needs

The prow-beast, hostile monster of the mast

With his strength hews out a file

On ocean’s even path, showing no mercy

Egil Skallagrimsson

Table of Contents

Cover Page

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

Maps

AUSTRGOTALAND, 975AD

ONE

TWO

THREE

FOUR

FIVE

SIX

SEVEN

EIGHT

NINE

TEN

ELEVEN

TWELVE

THIRTEEN

FOURTEEN

FIFTEEN

SIXTEEN

SEVENTEEN

EIGHTEEN

NINETEEN

HESTRENG, high summer

HISTORICAL NOTE

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Also by Robert Low

Copyright

About the Publisher

Maps

AUSTRGOTALAND, 975AD

The sun stayed veiled behind lead clouds streaked with silver. The rain hissed and the sea heaved, black and sluggish as a walrus on a rock, while a wind dragged a fine smoke of spray into my eyes.

‘Not storm enough,’ Hauk Fast-Sailor declared and he had the right of it, for sure. There was not enough of a storm to stop our enemies from coming up the fjord with the wind in their favour and that great, green-bordered sail swelled out. On a ship with a snarling serpent prow that sail looked like dragon wings and gave the ship its name.

The oars on the Fjord Elk were dipped, but moving only to keep the prow beast snarling into the wind that drove the enemy down on us; there was no point in tiring ourselves – we were crew-light, after all – while the enemy climbed into their battle gear. When we saw their sail go down would be the time for worry, the time they were ready for war.

Instead, men kept their hands busy tightening straps and checking edges, binding back their hair as it whipped in the wind. All of Jarl Brand’s lent-men from Black Eagle were here, save six with Ref and Bjaelfi who were herding women and weans and thralls away from Hestreng hall and up to the valley, with as much food and spare sail for tentage as they could carry. Away from the wrath of Randr Sterki and the snarlers on Dragon Wings.

I hoped Randr Sterki would content himself with looting and burning Hestreng, would not head inland too far. I had left him wethers and cooped hens and pigs to steal, as well as a hall and the buildings to burn – and if it was the Oathsworn he wanted…well, here we were, waiting for him at sea.

Still, I knew what drove Randr to this attack and could not blame him for it. I had the spear in my throat and the melted bowels that always came with the prospect of facing men who wanted to cleave sharp bars of metal through me but, for once, did not wish to be elsewhere. This was where I had to be, protecting the backs of mine and all the other fledglings teetering on flight’s edge, from the revenge of raiding men.

Men like us.

Gizur, swinging down from stay to stay through the ranks of men, looked like a mad little monkey I had seen once in Serkland, his weather-lined face such a perfect replica that I smiled. He was surprised at that smile, considering what we faced, then grinned back.

‘We should ship oars, Jarl Orm, before they get splintered.’

I nodded; when the ships struck, the oars on that side would be a disaster to us if we left them out. There was a flurry and clatter as the oars came in and were stacked lengthways; men cursed as shafts dunted them and now I saw the great snarling prow of Dragon Wings clearly, heard the faint shrieks and roars, saw the weapon-waving.

I was watching them flake the sail down to the yard when two of Jarl Brand’s lent-men shoved through our throng, almost to the Fjord Elk’s prow, nocking arrows as they went, stepping over bundled oars and shoving folk aside. They shot; distant screams made our own men roar approval – then curse as an answering flight zipped and shunked into the woodwork. One of the bowmen, Kalf Sygni, spun half round and clutched his forearm where a shaft was through, side to side.

‘Missed that coming,’ bellowed Finn, hefting his shield as he moved to the prow, clashing ring-iron shoulders with Nes-Bjorn, who was headed the same way; they glared at each other.

‘I am Jarl Brand’s prow man on the Black Eagle,’ Nes-Bjorn growled.

‘You are not on the Black Eagle,’ Finn pointed out and, reluctantly, the big man gave way, letting Finn take his place. Across on Dragon Wings his counterpart, hero-warrior of his boat, stepped up, mailed, helmeted and carrying a shield, but nothing better than a ship-wood axe.

They had the sail down and the oars shipped, leaving Dragon Wings with enough momentum to crash on us, rocking the Elk sideways to the waterline, staggering men who had been unprepared for it. Randr’s crew howled and axes clattered over our side, causing men to duck and raise shields – the axe-owners hauled hard at the ropes ringed to the shafts, pulling the hooked heads tight to the inside of the Elk with their iron beards, clinching us close as lovers.

A man screamed as his leg went with such a pull, trapping him like a snared fox against the side while he beat and tugged. Holger, I remembered dully as he screamed his throat out in agony. His name was Holger.

An arrow skittered off the mast and whipped past my head; I wore no ring-coat, for I was not so sure I could wriggle out of it in time if I fell overboard. Botolf, who stood on my right, heard me curse and grinned.

‘Now you know what it feels like,’ he yelled and I laughed into his mad delight, for it was a long-standing joke that Botolf had never found a ring-coat big enough to fit him. Then he threw back his head and roared out his name; Randr Sterki’s men shrieked and howled; the sides of the boats clashed and men flung themselves forward while the locked ships groaned and rocked.

The worst thing about battle, after a few bloodings drive away the first fears of it, is that it is work. The stink and the horror, the belly-wrenching terror and savage hatred of it were all things I had grown used to – but the backbreaking labour of it was what always made me blench. It was like ploughing stony ground, where the stones rise up and try to hit you and the whole affair leaves you sick and tremble-legged with exhaustion. The one good part about being jarl was that you did not sink into the grind of it, at least not all at once – but you had to stand like a tree in a boiling flood and seem unconcerned.

I stood rock-still and guarded by Botolf’s shield, watching the Dragon Wings crew pile forward in a rush, dipping both ships almost into the water with their weight. They struggled and hacked and died on the thwart-edges, my picked men darting in to cut the ropes that bound us together, or shoot out the men on Dragon Wings whose task it was to haul us tight.

They were red-mouthed screamers, Randr Sterki’s crew, waving spears and axes, garbed in leather and some in no more than makeshift breastplates of knotted rope. They had helms of all kinds, none of them fine craftings, and waved blades as notched as a dog’s jaw – even Randr Sterki’s ring-mailed prow man wielded no better than an adze-axe. Yet they had the savagery of revenge in them and that made the arm strong and the edge sharp.

Randr stood and roared out unheard curses in the middle of his ship, in the middle of a group as unlike the men round them as sheep-droppings in snow. They made my knees turn to water, those men whose eyes stared and saw nothing, who wore only thick, hairy hides over their breeks, who champed flecks of foam onto the thicket of their beards and hefted weapons with an easy skill and arms blood-marked with strength runes. Some of them, I noted, had swords, well-worn and well-earned.

‘Bearcoats!’ yelled Botolf in my ear. ‘He has bearcoats, Orm…’

Even as he spoke I saw them, all twelve of them, stir like a wolf pack scenting a kill. Bearcoats – berserker – had been no part of Randr Sterki’s crew before. Where had he got them from? My mouth went dry; I saw them snarling and howling, slamming into those of their own side who did not see them in time to get out of the way.

The first of them, tow-haired, tangle-bearded, reached the side and howled out to the sky, then hurled himself over on my men before the cords of his neck had slackened; they hacked at him with the desperate fury of those too trapped to run. The rest of the pack began to follow and Randr Sterki urged them on with bellows from the middle of his ship, his face red and ugly with rage and battle.

‘We shall have to kill Pig-Face,’ panted Nes-Bjorn, suddenly on my other side, pointing to Randr. If he was cursing at having been left behind by Jarl Brand to serve with us on this seemingly bad-wyrded day, his cliff of a face did not show it.

‘First stop the bearcoats,’ I pointed out, as calmly as I could while watching Tow-Hair carve his way towards me, trailing blood and screams; Botolf hefted his shield and byrnie-biter spear and braced himself on his one good leg. I raised my own sword a little, as if only resting it lightly on one shoulder, while my throat was full of my heart at the sight of a berserker slashing a path straight to me.

‘Ach,’ said Nes-Bjorn with a dismissive wave of his bearded axe. ‘We have our own man for that.’

At which point came a growling grunt from behind me, so like the coughing charge-roar of a boar that I half-spun in alarm. Then a half-naked figure with skin-marks of power and an axe in either hand launched straight over the heads of my own men, scattering them as he clattered into the howling bearcoat. Tow-Hair went down in a bloody eyeblink and the axes flailed on in Stygg Dusi’s fists, his carefully applied skin-marks streaked with blood, as he hurled himself in a bellowing whirl of arms and legs and axes over the side and into the crowded Dragon Wings. Men scattered before him.

‘Stygg Dusi,’ Nes-Bjorn pointed out and split a feral grin as the man by-named Shy Calm howled and chopped and died hard in the middle of the enemy ship.

‘There are twelve of them,’ I offered and Nes-Bjorn scowled.

‘Eleven now – no, ten, for Stygg has done well. Have you a point to make, Jarl Orm of the Oathsworn, or are you just after showing your skill at tallying?’

Then he elbowed men aside to reach the prow, where Finn, gasping and exhausted, had been forced to step back, ropey strings drooling from his mouth. The Dragon Wings prow man was nowhere to be seen.

I listened and watched as Stygg Dusi served out the last seconds of what the Norns had woven for him from the moment he slithered wetly into the world. Everything he had done had led to this place, this moment, and I raised my sword to the life he honoured us with, almost envied him in the certainty of his place in Valholl. Not yet, but soon, I was thinking, the old message we gave to all the dying to take with them to those gone before. Very soon now, it seemed.

The last rope was cut; Kalf Sygni, with the arrow still through his forearm, managed to shoot the last rope-hauler and the ships drifted apart from the stern, so that the prow beasts bobbed and snarled, almost seeming to strike out at each other. Men from both crews, trapped on the wrong boat, tried to fight their way to a thwart edge and leap for it.

Everything after that became a blur to me. I remember shoulder-charging a man, sending him flying into the water and it was only when he floundered there that I saw he wore a bearcoat. Finn loomed up, shook slaver and blood from his face, then launched back into the mad struggle, roaring curses and insults.

Hauk Fast-Sailor went down under the frenzied, raving chops of a wet-mouthed trio of bearcoats; Onund Hnufa went over the side, blood streaming from a cut on his head, and a man bound in knotted rope came at me, so that I had to kill him. By the time I looked, Onund had gone and I did not know if he had surfaced or not.

Something small and dark flew at the prow and Nes-Bjorn batted it contemptuously to one side. Flame engulfed him. Just like that. One minute he was roaring invites for someone to face him, the next minute he was enveloped in flame, a pillar of fire staggering about the prow. He fell back and men shrieked; one scrambled away screaming and batting at the flames on his leg, but that only caused his hands to flare. Another flung away a flaming shield, which hit the water and sank – but the water continued to burn in a circle.

‘Magic!’ yelled a voice, but it was no rune-curse, this. I had seen it before and the second little pot smacked into the Elk’s prow and burst into flames exactly as Roman Fire was supposed to. I watched the flames leap up the proud horns of Botolf’s carving, saw ruin in them even as the frantic crew of Dragon Wings saw those same flames leap to their own ship. Then Botolf yelled out that there was a second ship.

A second ship. Roman Fire. Bearcoats. These had been no part of Randr Sterki before now. I blinked and stared, my thoughts wheeling like the embers of my burning ship while men struggled and slipped and died, raving curses.

‘Orm – on your steerboard…’

I half-turned into a wet-red maw, where spittle skeined like spume off a wave. He had a greasy tangle of wild hair and eyes as mad as a kennel of frothing dogs, while the axe in his hand seemed as big as a wagon tree. I swung and missed, felt my sword bite into the wood of the mast, where it stuck.

I got my shield in the way a little, so that his axe splintered it and tore it sideways, out of my finger-short grasp. His whole body hit me then and there was a moment when I smelled the woodsmoke and grease stink of his pelt, the rankness of his sweat. My hand was wrenched from the hilt of my trapped sword.

Then there was only the whirl of silver sky and dark water and the great, cold plunge, like a hot nail in the quench.

ONE

Six weeks before…

The year cracked like a bad cauldron, just as winter unfastened its jaws a little and the cold ebbed to drip and yellow grass. Those from further south would say it was March and spring, but what did they know? It was still winter to us, who counted the seasons sensibly.

In the northlands we also know what causes the ground to move: it is the pain-writhing of Loki, when Loki’s wife has to empty her bowl, leaving her bound husband in agony, his face ravaged by the dripping poison of the serpent for the time it takes her to return and catch the venom again. The gods of Asgard gave dark Loki a hard punishment for his meddlings.

His writhings that year folded the cloak of the earth to new shapes with a grinding of stones, and great scarred openings, one of which swallowed an entire field close to us, kine and all.

A sign from the Aesir, Finn said moodily, echoing what others thought – that we should be back on the whale road and not huddled on land trying to be farmers. It was hard to ignore his constant low rumbling on the matter, harder still to put my head down and shoulder into the loud unspoken stares of the rest of them, day after day.

Odin had promised us fame and fortune and, of course, it was cursed, for he had not warned us to beware of what we sought so fiercely. Now that we had it, there was no joy in it for raiding men – what point raiding, as Red Njal grumbled, if you have silver and women enough? Nor was there any joy in trying to forsake the prow beast and cleave to the land, digging it up like worms, as Hlenni pointed out.

I heard them and their talk of the crushing wyrd of Odin. Others, still claiming to be Oathsworn, had wandered off into the world, with promises to be back at my side if the need arose, the old Oath binding them – We swear to be brothers to each other, bone, blood and steel, on Gungnir, Odin’s spear, we swear, may he curse us to the Nine Realms and beyond if we break this faith, one to another.

I accepted their promises with a nod and a clasping of hands, to keep the Oath alive and them from harm, though I did not expect to see any of them again. Those who remained struggled with the shackles that kept them from following the prow beast. They plodded grimly through winters in the hope that better weather might bring a new spark to send them coldwards and stormwards. It never seemed to flare into a fire of any fierceness, all the same.

The only ones who no longer moaned and grumbled were Botolf and Short Eldgrim, the first because he was no good on a raiding ship with one timber leg and, besides, had Ingrid and a daughter he cared more about; the second had no clear idea half the time of where he was, the inside of his head knocked out of him in a fight years before.

Finn had bairned Thordis in the fever that followed our return, silver-rich and fame-rich, and now she cradled their son, Hroald, in a sling of her looped apron. Finn looked at the boy every day with a mix of pride and misery, the one for what every father felt, the other for the forging of another link in a chain that chafed, for Thordis hourly expected a marriage offer.

On the other hand, when I looked across at Thorgunna and she let me know with her eyes that her own carrying was fine, there were no words, no mead of poetry that described how I felt at the news. It was a joy doubled, for she had lost a bairn before this and to find that it had not broken Thorgunna as a mother was worth all the silver Odin had handed us.

Yet the dull haar of disappointed men hung over Hestreng, so that the arrival of young Crowbone in a fine ship brought heads up, sniffing eagerly at his fire and arrogance like panting dogs on a bitch’s arse.

Crowbone. Olaf Tryggvasson, true Prince of Norway and a boy of twelve whose fair fame went before him like a torch and was so tied in with my own that swords and axes were lowered, since no-one could believe Crowbone had come to raid and pillage his friend, Orm of Hestreng.

He sat in my hall rubbing sheep fat into his boots, the price you pay for being splendidly careless and leaping off the prow of a fine ship into the salt-rotting shallows.

I had not seen him in three years and was astounded. I had left a nine-year-old boy and now found a twelve-year-old man. He was sharp-chinned and yellow-haired, his odd-coloured eyes – one brown as a nut, the other blue-green as sea ice – were bland as always and his hair was long enough to whip in the wind, though two brow braids swung, weighted with fat silver rings woven into the ends. I was betting sure that the one thing he wanted, above all else, was to grow hair on his chin.

He wore red and blue, with a heavy silver band on each arm and another, the dragon-ended jarl torc of a chief, at his neck. He had a sword, cunningly made for his size, snugged up in a sheath worked with snake patterns and topped and tailed with bronze. He had come a long way in the three years since I had freed him from where he had been chained by the neck to the privy of a raider called Klerkon.

I said that to him, too, and he smiled a quiet smile, then answered that he had not come as far as me, since he had started as a prince and I had come to being jarl of the legendary Oathsworn from being a gawk-eyed stripling of no account. Which showed what he had learned in oiled manners and gold-browed words at the court of Vladmir.

‘A fine ship,’ I added as his growlers, all ringmail and swagger, filed in to argue places by the hearthfire. He swelled with pride.

‘Short Serpent is the name,’ he declared. ‘Thirty oars a side and room for many more men besides.’

‘Short Serpent?’ I asked and he looked at me, serious as a wrecking.

‘One day I will have one bigger than this,’ he replied. ‘That one I will call Long Serpent and it will be the finest raiding ship afloat.’

‘Is Hestreng ripe for a strandhogg, then?’ I asked dryly, for already the fame of this boy was known in halls the length of the Baltic, where he had been hit-and-run raiding – the strandhogg – all year.

Crowbone only grinned and shook his head so that the rings tinkled. Then I saw they were not rings at all, but coins with holes punched through them and Crowbone’s grin grew wider when he saw I had spotted that. He fished in his pouch and brought out another, a whole one, which he spun at me until I made it vanish in my fist.

‘I took it and its brothers and cousins from traders bound for Kiev,’ Crowbone said, still grinning. ‘We will choke the life from Jaropolk before we are done.’

I looked at it – a glance was all it took, for minted silver was rare enough for me to know all the coins that whirled like bright foam along the Baltic shores. It was Roman, a new-minted one they call miliaresion and silver-light compared with other, older cousins that spilled out of Constantinople, which we called Miklagard, the Great City. The ones Crowbone had braided into the ends of his hair were gold nomisma, seventy-two to a Roman pound and, I saw, with the head of Nicepheros on them, which made them recent – and one-quarter light.

I said this as I spun it back to him and he grinned, suitably admiring my skill. He had skills of his own when it came to coinage, all the same – backed by the ships and men of Vladimir, Prince of the Rus in Novgorod, he had ravaged up and down the Baltic to further the cause of his friend against Vladimir’s brothers, Jaropolk and Oleg. They were not quite at open war, those three Kievan brothers, but it was a matter of time only and the trade routes in their lands were ravaged and broken as a result.

That and the lack of silver from the east that made Crowbone’s coin rare – and light – also made any trade trip there worthless unless you went all the way down the rivers and cataracts to the Great City. I said as much while Thorgunna and the thrall women served platters and ale and Crowbone grinned cheerfully, uncaring little wolf cub that he was.

A shadow appeared at his elbow and I turned to the mailed and helmeted figure who owned it; he stared back at me from under his Rus horse-plume and face-mail, iron-grim and stiff as old rock.

‘Alyosha Buslaev,’ declared little Crowbone with a grin. ‘My prow man.’

Vladimir’s man more like, I was thinking, as this Alyosha closed in on Crowbone like a protecting hound, sent by the fifteen-year-old Prince of Novgorod to both guard and watch his little brother-in-arms. They were snarling little cubs, the Princes Vladimir and Olaf Crowbone, and thinking on them only made me feel old.

The hall was crowded that night as we feasted young Crowbone and his crew with roast horse, pork, ale and calls to the Aesir, for Hestreng was still free of the Christ and mine was still the un-partitioned hall of a raiding jarl – despite my best efforts to change that. Still, as I told Crowbone, the White Christ was everywhere, so that the horse trade was dying – those made Christian did not fight horses in the old way, nor eat the meat.

‘Go raiding,’ he replied, with the air of someone who thought I was daft for not having considered it. Then he grinned. ‘I forgot – you do not need to follow the prow beast, with all the silver you have buried away under moonlight.’

I did not answer that; young Crowbone had developed a hunger for silver, ever since he had worked out that that was where ships and men came from. He needed ships and men to make himself king in Norway and I did not want him snuffling after any moonlit burials of mine – he had had his share of Atil’s silver. That hoard had been hard come by and I was still not sure that it was not cursed.

I offered horn-toasts to the memory of dead Sigurd, Crowbone’s silver-nosed uncle, who had been the nearest to a father the boy had had and who had been Vladimir’s druzhina commander. Crowbone joined in, perched on the high-backed guest bench beside me, his legs too short to rest his feet like a grown man on the tall hearthstones that kept drunk and child from tumbling in the pitfire.

His men, too, appreciated the Sigurd toasts and roared it out. They were horse-eating men of Thor and Frey, big men, calloused and muscled like bull walruses from sword work and rowing, with big beards and loud voices, spilling ale down their chests and boasting. I saw Finn’s nostrils flare, drinking in the salt-sea reek of them, the taste of war and wave that flowed from them like heat.

Some of them wore silk tunics and baggier breeks than others, carried curved swords rather than straight, but that was just Gardariki fashion and, apart from Alyosha, they were not the half-breed Slavs who call themselves Rus – rowers. These were all true Swedes, young oar-wolves who had crewed with Crowbone up and down the Baltic and would follow the boy into Hel’s hall itself if he went – and Alyosha was at his side to make the sensible decisions.

Crowbone saw me look them over and was pleased at what he saw in my face.

‘Aye, they are hard men, right enough,’ he chuckled and I shrugged as diffidently as I could, waiting for him to tell me why he and his hard men were here. All that had gone before – politeness and feasting and smiles – had been leading to this place.

‘It is good of you to remember my uncle,’ he said after a time of working at his boots. The hall rang with noise and the smoke-sweat fug was thicker than the bench planks. Small bones flew; roars and laughter went up when one hit a target.

He paused for effect and stroked his ringed braids, wanting moustaches so badly I almost laughed.

‘He is the reason I am here,’ he said, raising his voice to be heard. It piped, still, like a boy’s, but I did not smile; I had long since learned that Crowbone was not the boy he seemed.

When I said nothing, he waved an impatient little hand.

‘Randr Sterki sailed this way.’

I sat back at that news and the memories came welling up like reek in a blocked privy. Randr the Strong had been the right-hand of Klerkon and had taken over most of that one’s crew after Klerkon died; he had sailed their ship, Dragon Wings, to an island off Aldeijuborg.

Klerkon. There was a harsh memory right enough. He had raided us and lived only long enough to be sorry for it, for we had wolfed down on his winter-camp on Svartey, the Black Island, finding only his thralls and the wives and weans of his crew – and Crowbone, chained to the privy.

Well, things were done on Svartey that were usual enough for red-war raids, but men too long leashed and then let loose, goaded on by a vengeful Crowbone, had guddled in blood and thrown bairns at walls. Later, Crowbone found and killed Klerkon – but that is another tale, for nights with a good fire against the saga chill of it.

Randr Sterki had a free raiding hand while matters were resolved with Prince Vladimir over the Klerkon killing, but when all that was done, Vladimir sent Sigurd Axebitten, Crowbone’s no-nose uncle and commander of his druzhina, to give Randr a hard dunt for his pains.

Except Sigurd had made a mess of it, or so I heard, and Crowbone had grimly followed after to find Randr Sterki and his men gone and his uncle nailed to an oak tree as a sacrifice to Perun. His famous silver nose was missing; folk said Randr wore it on a leather thong round his neck. Crowbone had been wolf-sniffing after his uncle’s killer since, with no success.

‘What trail did he leave, that brings you this way?’ I asked, for I knew the burn for revenge was fierce in him. I knew that fire well, for the same one scorched Randr Sterki for what we had done to his kin in Klerkon’s hall at Svartey; even for a time of red war, what we had done there made me uneasy.

Crowbone finished with his boots and put them on.

‘Birds told me,’ he answered finally and I did not doubt it; little Olaf Tryggvasson was known as Crowbone because he read the Norns’ weave through the actions of birds.

‘He will come here for three reasons,’ he went on, growing more shrill as he raised his voice over the noise in the hall. ‘You are known for your wealth and you are known for your fame.’

‘And the third?’

He merely looked at me and it was enough; the memory of Klerkon’s steading on Svartey, of fire and blood and madness, floated up in me like sick in a bucket.

There it was, the cursed memory, hung out like a flayed skin. Fame will always come back and hag-ride you to the grave; my own by-name, Bear Slayer, was proof of that, since I had not slain the white bear myself, though no-one alive knew that but me. Still, the saga of it – and all the others that boasted of what the Oathsworn were supposed to have done – constantly brought men looking to join us or challenge us.

Now came Randr Sterki, for his own special reasons. The Oathsworn’s fame made me easy to find and, with only a few fighting men, I was a better mark to take on than a boatload of hard Rus under the protection of the Prince of Novgorod.

‘Randr Sterki is not a name that brings warriors,’ Crowbone went on. ‘But yours is and any man who deals you a death blow steals your wealth, your women and your fame in that stroke.’

It was said in his loud and shrill boy’s voice – almost a shriek – and it was strange, looking back on it, that the hall noise should have ebbed away just then. Heads turned; silence fell like a cloak of ash.

‘I am not easily felled,’ I pointed out and did not have to raise my voice to be heard. Some chuckled; one drunk cheered. Red Njal added: ‘Even by bears,’ and got laughter for it.