Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

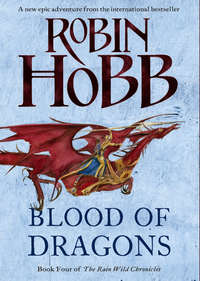

Kitabı oku: «Blood of Dragons», sayfa 3

That night, standing before them and recounting all she knew about the legendary pards from the Elderling manuscripts of old, and then revealing how she had pretended to be a much larger creature to panic the animal, had been rewarding. Their laughter at her tale had not been mocking but admiring of her courage.

She had a place now and a life, and it was one of her own making.

Day the 22nd of the Fish Moon

Year the 7th of the Independent Alliance of Traders

From Kim, Keeper of the Birds, Cassarick

To Winshaw, General Registrar of Birds, Bingtown

I think it is ridiculous that a simple accounting error is leading to suspicions and accusations against me. I have told the Council numerous times that I am the victim of prejudice simply because I came to this post as a Tattooed rather than as one Rain Wilds born. The current journeymen feel a loyalty to their own kind that leads to this sort of suspicion and tattling. As they seem to have nothing better to do than spread evil rumours, I have doubled their duty hours.

Yes, there is a discrepancy between the number of birds in our cotes now and the number that existed before the red lice plague completely subsided. It is for a simple reason: Birds died.

In the crisis of the moment, I did not pay as much attention to paperwork as I did to attempting to keep birds alive. For this reason, yes, I burned dead birds before other bird keepers had witnessed that they were, indeed, dead. It was to stop the spread of contagion. And that is all it was.

I cannot give you evidence of their deaths, unless you wish me to ship a package of ashes from the incineration site. I do not think that is a task worthy of my time.

Do you?

Kim, Keeper of the Birds, Cassarick

Postscript: If any keeper sites are in need of journeymen, I have a surplus, and will gladly release any of them for service. The sooner my own apprentices can replace those disloyal to me, the sooner the operation of the Cassarick station will become more efficient and professional.

CHAPTER THREE

Hunters and Prey

Sintara waded out of the river, cold water sheeting from her gleaming blue scales. When she reached the shore, she opened her wings, rocked back on her hind legs, and shook them, showering the sandy bank with droplets. As she folded them sleekly back to her sides, she feigned oblivion to how every dragon eye was fixed on her. She let her gaze rove over all of them, staring dragons and frozen keepers.

Mercor broke the silence. ‘You look well, Sintara.’

She knew it. It had not taken long. The long baths in simmering water, flights to muscle her and plenty of meat to put flesh on her bones. She finally felt like a dragon. She stood a moment longer to allow them all to notice how she had grown before dropping to all fours again. She regarded Mercor in silence for a few long moments before observing, ‘And you do not. Still not flying, Mercor?’

He did not look aside from her disdain. ‘Not yet. But soon, I hope.’

Sintara had spoken true. The golden drake had outgrown his flesh, as if the meat of his body were stretched too thinly over his bones. He was clean, meticulously groomed as ever, but he did not gleam as he once had.

‘He will fly.’

The words were confident. Sintara turned her head. Her focus on Mercor had been such that she had forgotten there were other dragons present, let alone a mere human. Several of the Elderling youths had paused at their tasks to watch their encounter, but not Alise. She was working on Baliper, and as her hands moved over a long gash on his face, she kept her eyes on her task. The gash was fresh; she was blotting blood and dirt from it, rinsing the rag in a bucket at her feet. Baliper’s eyes were closed.

Sintara did not reply to Alise’s assertion. Instead, she said, ‘So you are Baliper’s keeper now. Do you hope he will make you an Elderling? To give you a better life?’

The woman’s eyes flickered to Sintara and then back to her work. ‘No,’ she replied shortly.

‘My keeper is dead. I do not desire another one.’ Baliper spoke in a profoundly emotionless voice.

Alise stilled. She set one hand on the scarlet dragon’s muscular neck. Then she stooped, rinsed her rag, and went on cleaning the gash.

‘I understand that,’ she said quietly. When she spoke to Sintara, her voice echoed Mercor’s exactly. ‘Why did you come here?’

It was an irritating question, not just because they both dared to ask her but because she was not, herself, certain of the answer. Why had she come? It was undragonlike to seek companionship with either other dragons or humans. She looked for a moment at Kelsingra, recalling why the Elderlings had created it: to lure dragons. To offer them the indulgences that only a city built by humans could provide.

Something that Mercor had said long ago pushed into her thoughts. They had been discussing Elderlings and how dragons changed humans. She tried to recall his exact words and could not. Only that he had claimed humans changed dragons just as much as dragons changed humans.

The thought was humiliating. Almost infuriating. Had her long exposure to humans changed her, given her a need for their company? Her blood coursed more strongly through her veins and her body answered her question. Not just company. She felt the wash of colour go through her scales, betraying her.

‘Sintara. Was there a reason for this visit?’

Mercor had moved closer still. His voice was almost amused. ‘I go where I please. Today, it pleased me to come here. Today it pleased me to look on what might have been drakes.’

He opened his wings, stretched them wide. They were larger than she recalled. He flexed them, testing them, and the breeze of them, heavy with his male scent, washed over her. ‘It pleases me that you have come here, as well,’ he observed.

A sound. Had Alise laughed? Sintara snapped her gaze back to the woman, but her head was bent over her bucket as she wrung out her rag. She looked back at Mercor. He was folding his wings carefully. Kalo was watching both of them with interest. As was Spit. As she looked at him, the silver male reared back onto his hind legs and spread his wings as wide as they would go. Carson stood between them, looking very apprehensive. ‘It needn’t be Mercor!’ the nasty little silver trumpeted suddenly. ‘It could be me.’

She stared at him and felt her poison sacs swelling in her throat. He flapped his wings at her, releasing musk in a rank wind. She shook her head and bent her neck, snorting out the stench. ‘It will never be you,’ she spat at him.

‘It might,’ he countered and danced a step toward her. Kalo’s eyes suddenly spun with anger.

‘Spit!’ Carson warned him but the silver pranced another step closer.

Kalo lifted a clawed foot, set it deliberately on his tail. Spit squalled angrily and turned on the much larger dragon, opening his mouth wide to show his poison glands, scarlet and distended. Kalo trumpeted his challenge as he snapped his wing open, bowling the smaller dragon to one side as Carson leapt back with a roar of dismay to avoid being crushed.

Kalo ignored the chaos behind him.

‘I will fly the challenge!’ the cobalt drake announced. He lifted his gaze to Sintara. She heard a distant cry and became aware that far overhead, Fente was circling. The small green queen watched it all with interest. The heat of Kalo’s stare swept through her, and suddenly all she felt was anger, anger for all of them, all the stupid, flightless, useless males. A rippling of colour washed through her skin and echoed in her scales.

‘Fly the challenge?’ she roared back at all of the staring drakes. ‘You fly nothing; none of you fly! I came to see it again, for myself. A field of drakes, as earthbound as cows. As useless to a queen as the old bones of a kill.’

‘Ranculos flies. Sestican flies,’ Alise pointed out relentlessly. ‘Two drakes at least have achieved flight. If they were the drakes you wanted …’

The insult was too great. This time, Sintara spat acid. A controlled ball of it hit the earth a body’s length from Alise. Baliper surged to his feet, eyes spinning sparks of rage. As he charged, Alise shrieked and ran. A spike on one knob of his outflung wings narrowly missed her. Sintara braced herself, flinging her own wings wide, but cobalt Kalo intercepted Baliper. As the two males slammed into one another, feinting with open mouths and slashing with clawed wings, the air was filled with the shouts and screams of Elderlings. Some fled, others raced toward the combatants.

Sintara had only a moment to take in the spectacle before Mercor knocked her down. Gaunt as he was, he was still larger than she was. As she sprawled on the turf, he reared up over her and she expected him to spray her with venom. Instead he came down almost gently, his heavy forefeet pinning her wings to the earth and pressing painfully on the flexible bones.

She opened her jaws to spew acid at him. He darted his head down, his mouth open wide to show her his swollen acid glands. ‘Don’t,’ he hissed at her, and the finest mist of golden acid rode his word. The stinging kiss of it enveloped her head and she flung her face aside from it.

He rumbled out his words, so that the others heard, but he pressed them strongly into her mind at the same time. ‘You are impatient, queen. Understandably so. A little time more, and I will fly. And I will mate you.’ He reared onto his hind legs again, lifting his forefeet off her wings as he did so. She stood up awkwardly, muddied, her wings bruised and aching as she folded them back to her body and scrabbled away.

The battle between Baliper and Kalo had been brief; they stood at a distance from each other, snorting and posturing. Spit cavorted mockingly, a safe distance from the much larger drakes, randomly spitting acid as scampering keepers cried out warnings to one another. Sintara saw Alise watching her; the woman’s eyes were large and anxious. When she stared at the woman, she backed up, lifting her hands to shield her face. It only made Sintara angrier. She fixed her fury on Mercor.

‘Don’t threaten me, drake.’

He turned his head slightly sideways. His wings were still half-open, ready to deal a stunning slap if she sprang at him. He spoke quietly, only into her mind. Not a threat, Sintara. A promise.

As he closed his wings, his musk wafted toward her again. She knew her scales flushed with colours in response, the reflexive biological response of a queen in oestrus. His black eyes whirled with interest.

She lifted onto her hind legs and turned away from him. As she sprang into the sky, she trumpeted, ‘I hunt where I will, drake. I owe you nothing.’ She beat her wings in hard, measured strokes, rising above them all.

In the distance, green Fente trumpeted, shrill and mocking.

‘Thymara!’

She turned slowly at the sound of Tats’s greeting. Tension knotted in her belly. She had been avoiding this conversation. She’d seen in Tats’s eyes when she first returned from Kelsingra that he knew what had happened between her and Rapskal. She hadn’t needed or wanted to discuss it with him. On the days since then, she had not avoided him completely, but she had thwarted his efforts to find her alone. She had found it almost as difficult as avoiding being alone with Rapskal. Tats had been subtle about trying to corner her. Rapskal had shown up on her doorstep the evening they had returned from Kelsingra, smiling far too knowingly when he asked her if she’d care to go for an evening walk.

He had come to the door of the small cottage she shared with Sylve and ostensibly with Jerd as well. The three had moved in together almost as soon as the keepers had settled in the village. Thymara could not recall that it had been a much-discussed decision; it had just seemed logical that the only three female keepers would share lodgings.

Harrikin had helped them select which of the dilapidated structures they would claim as their own, and he had spent more than a few afternoons helping them make it habitable. Thanks to Harrikin, the chimney now drew the smoke out of the house, the roof leaked only when the wind was extremely strong, and there were shutters for the window openings. Furnishings were sparse and rough, but that was true of all the keepers’ homes. From Carson, they had crudely tanned deer hides stretched over pole frames as a basis for their beds, and carved wooden utensils for eating with. Thymara was one of the best hunters, so they always had meat, both to eat and to trade to other keepers. Thymara had enjoyed her evenings with Sylve, and enjoyed them even more when some of the other keepers came by to share the fireside and talk. At first, Tats had been a frequent guest there, as had Rapskal.

Jerd spent few nights there, returning sporadically to shuffle through her possessions for some particular item, or to share a meal with them while she complained about whichever of the males she was currently keeping company with. Despite her dislike for Jerd, Thymara could not deny a perverse fascination with her diatribes against her lovers. She was appalled at Jerd’s casual sexuality and her tempers, her spewing of intimate details and how frequently she discarded one male keeper to take up with another. She had cycled through several of the keepers more than once. It was no secret in their small group that Boxter was hopelessly infatuated with her. He alone she seemed to spurn. Nortel had been her lover for at least three turns of her heart, and copper-eyed Kase had the distinction of having literally put her out of his cottage as well as his bed. She had seemed as astonished as angered that he had been the one to put an end to their liaisons. Thymara suspected that Kase was loyal to his cousin Boxter and wanted no part of breaking his heart.

But that first evening after her time with Rapskal in Kelsingra, of course, Jerd had been home, and full of small and cutting comments. She took care to remind Thymara that Rapskal had once been her lover, however briefly, and that Tats, too, had shared her bed. Her presence had not made it any easier to tell Rapskal gently that she did not want to walk out with him that evening. It had been no easier to refuse him the next day, nor to put him off on the next. When finally she had told him that she doubted the wisdom of what she had done, and that her fear of conceiving a child was greater than her lust for him, Rapskal had surprised her by nodding gravely.

‘It is a concern. I will take it on myself to find out how Elderlings once prevented conception, and when I know it, I will tell you. After that we can enjoy ourselves without fear.’ He had said these words as they walked hand in hand along the riverbank, only a few evenings ago. She had laughed aloud, both charmed and alarmed, as she always was, by his childlike directness about things that were definitely not childish.

‘So easily you set aside all the rules we grew up with?’ she asked him.

‘Those rules don’t apply to us any more. If you’d come back to Kelsingra with me and spend a bit more time with the stones, you’d know that.’

‘Be careful of the memory-stone,’ she had warned him.

It was another rule they had grown up with. All Rain Wild children knew the danger of dallying in the stored memories in the stones. More than one youngster had been lost to them, drowned in memories of other times. Rapskal had shrugged her concerns aside.

‘I’ve told you. I use the stones and the memories they hold as they were intended. Some of it, I now understand, was street art. Some of them, especially the ones in the walls of homes, were personal memories, like a diary. Some are poetry, especially in the statues, or histories. But there will be a place where the Elderlings stored their magic and their medicines, and when I discover it, there I think I will find what we need. Does that comfort you?’

‘Somewhat.’ She decided that she did not have to tell him right then that she was not sure if she would take him into her bed even if she knew it was safe to do so. She was not sure she could explain her reluctance. How could she explain to him what she did not understand herself? Easier not to talk about it.

Easier not to discuss Rapskal with Tats as well. So she turned to him now with a half-smile and an apologetic, ‘I was just about to go hunting. Carson has given me the Willow Ridge today.’

‘And me, also,’ Tats answered easily. ‘Carson wants us to hunt in pairs for safety. It’s not just Alise’s pards. Less chance that we’ll be spooking each other’s game away, too.’

She nodded dumbly. It had been bound to happen sooner or later. Since the keepers had gathered to discuss how best to encourage the dragons to fly, Carson had come up with a number of new ideas. Dividing the hunting territory to prevent conflicts and hunting with a partner for added safety had been one of them. Today, some keepers would be hunting the Long Valley, others the High Shore, and some would be fishing. The Willow Ridge paralleled the river and was, as they had named it, forested mostly with willow. It was prime range for deer to browse, and Carson had reserved it for his best bow-hunters.

She had her gear and Tats had his. There was no excuse not to set out immediately. After the morning’s conflict, Thymara had wanted to flee. Even though Sintara had taken no notice of her, had possibly not even seen her watching from the riverside, Thymara felt shamed by her dragon. She had not wanted to be around the other keepers; she didn’t want to hear what they would be saying about her spoiled queen. Worse was that she kept trying to find a way to justify Sintara’s arrogance and spite. She wanted to be able to defend her dragon. Sintara cared little or nothing for her. She knew that. Yet every time she thought she had divorced her feelings from the blue queen, every time she was sure she had made herself stop caring about her dragon, Sintara seemed to find a new way to wring emotions from her. Today it was shame.

She tried to shake herself free of it as Tats fell into step beside her. It wasn’t her fault. She had done nothing, but it did not help to know that. As they crossed the face of the meadow and passed the other keepers and the dragons, she told herself she was imagining that they were staring after her.

Kase, Boxter, Nortel and Jerd had drawn grooming duty for the day. They were going over the earthbound dragons, checking for sucking parasites near their eyes and ear-holes while encouraging them to stretch out their wings. Arbuc was cooperating in his sweet but rather dim way while Tinder paced impatiently while awaiting attention. Ever since the lavender dragon’s colours had started to develop, he had shown a dandyish side that had several of the keepers chuckling about his vanity. Alise was smoothing deer tallow into the new scratches that Kalo had given Baliper.

Once the dragons had been groomed, the keepers would encourage each of the remaining dragons to make an effort at flight. Only after they had complied, at least nominally, would they be fed. Carson insisted.

Thymara did not envy them their tasks. Of the dragons, only Mercor was patient when hungry. Spit was as foul-tempered, obnoxious and rude a creature as she’d ever met. Even Carson could barely manage him. Nasty little Fente had been able to take flight, thank Sa, but gloriously green-and-gold Veras remained earthbound, and she was as vindictive as her keeper, Jerd. Kalo, the largest of the dragons, was almost suicidally determined to fly. Davvie was his keeper but today it was Boxter tending the dragon’s numerous cuts and scratches he had acquired in his spat with Baliper. The spat that Sintara had provoked. Thymara walked faster. A day spent hunting and killing a deer and dragging it back to camp was definitely preferable to a day spent dealing with the other keepers and their dragons.

At least she no longer had to deal with her own dragon. She cast her eyes skyward as she thought of Sintara and tried to deny the pang of abandonment she felt.

‘Do you miss her?’ Tats asked quietly.

She almost resented that he could read her so clearly. ‘I do. She doesn’t make it easy. She touches my thoughts sometimes, for no reason that makes sense to me. She will suddenly be in my mind, bragging about the size of the bear she has killed, and how he fought but could not lay a claw on her. That was just a couple of days ago. Or she will suddenly show me something that she sees, a mountain capped with snow, or the reflection of the city in that deep river inlet. Something so beautiful that it leaves me gasping. And then, just like that, she’s gone. And I can’t even feel that she’s there at all.’

She hadn’t meant to tell him so much. He nodded sympathetically and then admitted, ‘I feel Fente all the time. Like a thread that tugs at my mind. I know when she’s hunting, when she’s feeding … that’s what she’s doing now. Some sort of mountain goat; she doesn’t like how his wool tastes.’ He smiled fondly at his dragon’s quirkiness, and then, as he glanced back at Thymara, his smiled faded. ‘Sorry. I didn’t mean to rub salt in the wound. I don’t know why Sintara treats you so badly. She’s just so arrogant. So cruel. You’re a good keeper, Thymara. You always kept her well groomed and well fed. You did better than most keepers. I don’t know why she didn’t love you.’

Her feelings must have shown on her face for he abruptly said, ‘Sorry. I always say the wrong thing to you, even when I think I’m stating the obvious. I guess I didn’t need to say that. Sorry.’

‘I think she does love me,’ Thymara said stiffly. ‘As much as dragons can love their keepers. Well, perhaps “values” is a better word. I know she doesn’t like it when I groom one of the other dragons.’

‘That’s jealousy. Not love,’ Tats said.

Thymara said nothing. It was getting dangerously close to a prickly topic. Instead, she walked a bit faster, and chose the steepest trail up the ridge. ‘This is the shortest path,’ she said, although he hadn’t voiced an objection. ‘I like to get as high as I can, and then hunt looking down on the deer. They don’t seem as aware of me when I’m above them.’

‘It’s a plan,’ Tats agreed, and for a time the climb took all their breath.

She was glad not to talk. The morning air was fresh, and the day would have been cold if she had not been putting so much effort into the climb. The rain remained light, and the budding branches of the willows caught some of it before it touched them. They reached the crest of the ridge, and she led them upriver. When she struck a game trail she had not followed before, she took it. She had decided, without consulting Tats, that they needed to range farther than usual if they were to find any sizeable game. She intended to follow the ridge line, scouting new hunting territory as well as, she hoped, bringing home a large kill today.

Silence had enveloped them since the climb. Part of it was the quiet of the hunter, part of it was that she didn’t wish to talk about difficult things. Once, she recalled, her silences with Tats had been comfortable, the shared silences of friends who did not always need words to communicate. She missed that. Without thinking, she spoke aloud. ‘Sometimes I wish we could go back to how things were between us before.’

‘Before what?’ he asked her quietly.

She shrugged one shoulder and glanced back at him as they walked in single file along the game trail. ‘Before we left Trehaug. Before we became dragon keepers.’ Before he had mated with Jerd. Back when romance and sexuality had been forbidden to her by the customs of the Rain Wilds. Before Tats had made it clear that he wanted her and stirred her feelings for him. Before life had become so stupidly complicated.

Tats made no response and for a short time she lost herself in the beauty of the day. Light streamed down through breaks in the overcast. The wet black branches of the willows formed a net against the grey sky. Here and there, isolated yellow leaves clung to the branches. Under their feet, the fallen leaves were a deep sodden carpet, muffling their footfalls. The wind had quieted; it would not carry their scent. It was a hunter’s perfect day.

‘I wanted you even then. Back in Trehaug. I was just, well, scared of your father. Terrified of your mother. And I didn’t know how to talk to you about it. It was all forbidden then.’

She cleared her throat. ‘See how the trail forks there, and the big tree above it? If we climb it, we can have a clear view in all directions, and a good shot at anything that comes that way. Plenty of room for both of us to have a clear shot if we get one.’

‘I see it. Good plan,’ he said shortly.

Her claws helped her to make the ascent easily. The trees of this area were so small compared to those of her youth that she’d had to learn a whole new set of climbing skills. She had one knee locked around a branch and was leaning down to offer Tats a hand when he asked, ‘Are you ever going to talk to me about it?’

He had hold of her hand and his face was inches from hers, looking up at her. She was mostly upside down, and could not avoid his gaze. ‘Do we have to?’ she asked plaintively.

He gave her some of his weight and then came up the tree so easily that she suspected he could have done it by himself all along. He settled himself on a branch slightly higher than hers, his back to the trunk, facing in the opposite direction so he could watch a different section of trail. For a short space of time, both of them were quiet as they arranged arrows to be handy and readied their bows. They settled. The day was quiet, the river’s roar a distant murmur. She listened to bird calls. ‘I want to,’ Tats said as if no time had passed at all. ‘I need to,’ he added a moment later.

‘Why?’ she asked, but she knew.

‘Because it makes me crazy to wonder about it. So I just want you to tell me, just so I know, even if you think it will hurt me. I won’t be angry … well, I’ll try not to be angry and I’ll try not to show I’m angry if I am … but I have to know, Thymara. Why did you choose Rapskal and not me?’

‘I didn’t,’ she said, and then spoke quickly before he could ask anything. ‘This probably won’t make sense to you. It doesn’t make sense to me, and so I can’t explain it to you. I like Rapskal. Well, I love Rapskal, just as I love you. How could we have been through all we’ve been through together and not love one another? But it wasn’t about what I felt for Rapskal that night. I didn’t stop and think, “Would I rather be doing this with Tats?” It was all about how I felt about me. About being me, and that suddenly it was something I could do if I wanted to. And I did want to.’

He was quiet for a time and then said gruffly, ‘You’re right. That makes no sense to me at all.’

She hoped he was going to leave it at that, but then he asked, ‘So. Does that mean that when you were with me, you didn’t want to do it with me?’

‘You know I’ve wanted you,’ she said in a low voice. ‘You should know how hard it’s been to say no to you, and no to myself.’

‘But then you decided to say yes to Rapskal.’ He was relentless.

She tried to think of an answer that would make him understand. There wasn’t one.

‘I think I said yes to myself, and Rapskal happened to be the person who was there when I said it. That doesn’t sound very nice, does it? But there it is and it’s the truth.’

‘I just wish …’ His voice tapered off. Then he cleared his throat and made himself go on, ‘I just wish it could have been me. That you’d waited for me, that I’d been your first.’

She didn’t want to know why yet she had to ask. ‘Why?’

‘Because it would have been something special, something we could have remembered together for the rest of our lives.’

His voice had gone husky and sentimental but instead of moving her, it made her angry. Her voice went low and bitter as venom. ‘Like you waited for your first time to be with me?’

He leaned forward and turned his head to look at her. She felt him move, but would not turn her head to meet his gaze. ‘I can’t believe that still bothers you, Thymara. After all the time we’ve known each other, you should know that you’ve always meant more to me than Jerd ever could. Yes, that happened between us, and I’m not proud of it. It was a mistake. There. I admit it, it was a huge mistake, but I was stupid and, well, she was right there, offering it to me, and you know, I just think that it’s different for a man. Is that why you went to Rapskal? Because you were jealous? That makes no sense at all, you know. Because he was with Jerd, too.’

‘I’m not jealous,’ she said. And it was true. The jealousy had burned away, but she had to acknowledge the hurt that remained. ‘I’ll admit that there was a time when it really bothered me. Because I had thought there was something special between us. And because, in all honesty, Jerd rubbed my face in it. She made it seem like if I had you, then I was picking up her leavings.’

‘Her leavings.’ His voice went very flat. ‘That’s how you think of me? Something she discarded, so I can’t be good enough for you.’

Anger was building in his voice. Well, she was getting angry, too. He’d wanted her to tell him the truth, promised he wouldn’t get angry, but obviously he was now looking for any excuse to show her the anger he’d felt all along. Making it impossible to admit that, yes, she had since then rather wished it had been him rather than Rapskal. Tats was solid and real in her life, someone she had always felt she could count on as a partner. Rapskal was flighty and weird, exotic and compelling and sometimes dangerously strange. ‘Like the difference between bread and mushrooms,’ she said.

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.