Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

Kitabı oku: «The Raven’s Knot»

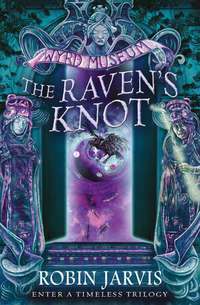

THE RAVEN’S KNOT

Robin Jarvis

Dedication

Tales from the Wyrd Museum Trilogy

The Woven Path The Raven’s Knot The Fatal Strand

For Young Adult readers:

Dancing Jax

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Prologue

Chapter 1 - Out of the Blackout

Chapter 2 - The Chamber of Nirinel

Chapter 3 - Thought and Memory

Chapter 4 - The Lord of the Dance

Chapter 5 - Jam and Pancakes

Chapter 6 - The Crow Doll

Chapter 7 - In the Shadow of the Enemy

Chapter 8 - Aidan

Chapter 9 - Spectres and Aliens

Chapter 10 - Valediction

Chapter 11 - Deceit and Larceny

Chapter 12 - Riding the Night

Chapter 13 - Memory Forgotten

Chapter 14 - Missing the Dawn

Chapter 15 - Drowning in Legends

Chapter 16 - Two Lost Souls

Chapter 17 - Skögul

Chapter 18 - Charred Embers

Chapter 19 - Verdandi

Chapter 20 - The Crimson Weft

Chapter 21 - Hlökk

Chapter 22 - The Tomb of the Hermit

Chapter 23 - The Gathering

Chapter 24 - Within the Frozen Pool

Chapter 25 - Battle of the Thorn

Chapter 26 - Dejected and Downcast

Chapter 27 - The Property of Longinus

Chapter 28 - Blood on the Tor

Epilogue

Copyright

About the Publisher

Prologue

Five miles outside Glastonbury

2.58 am

Brindled with bitter, biting frost, the plough-churned soil of the Somerset levels was bare and black. Hammered upon winter’s icy forge, the earthen furrows were iron hard – unyielding as the great cold which flooded the moonless dark.

Deep and chill were the silent shadows that filled those expansive fields. As sombre lakes of brooding gloom they appeared, pressing and pushing against the bordering hedgerows. Through those twisted, naked branches the unrelenting hoary darkness spilled and the night was drowned in a black, freezing murk that no glimmer of star could penetrate.

Behind the invisible distant hills, shimmering bleakly upon the rim of the choking night, the pale glare of mankind was weak and dim – the countless faint, orange lights trembling in the frozen air.

In that lonely hour, in the remote realm of the wild empty country, safely concealed by the untame dark, a sound – long banished from the world – disturbed the jet-vaulted heavens. Over unlit fields and solitary farm buildings, the noise of great wings travelled across the sky – free at last of the tethers that had kept them bound for so many ages.

All creatures felt the presence of that awful force which coursed through the knifing cold. Upon the shadow-smothered ground, farm animals grew silent and afraid as the terror passed high above.

Horror and dread spread across the dim landscape which separated Wells and Glastonbury. Owls refused to leave their barns and a fox, cantering leisurely homeward, suddenly flattened itself against the freezing ground when rumour of the unseen nightmare reached its sharp ears.

Dragging its stomach over frost-covered furrows, its brush quivering in fright, the fox darted for cover – tearing in blind panic towards a thicket of hawthorn. It lay there panting feverishly – straining to catch the slightest sound upon the winter airs.

But the unnatural clamour that had so alarmed the fox had already faded and a new, yet more familiar, noise was growing.

Through the night a vehicle came, the faint rumble of its engine a welcome distraction from the fear that had so gripped the fox’s heart and yet it remained crouching beneath the hawthorn until daybreak.

Over the icy road the car swept, the broad beams of its headlights scything through the dark veils in front – snatching brief, stark visions of hedge and ditch as they flashed by.

Inside the vehicle the heater was finally blowing hot air through the vents and the toes of the driver and his passenger were thawing at last. Mellow music issued from the radio, colouring the dark journey home with a languid harmony, reflecting the relaxed and sleepy mood of the car’s occupants.

Resting her head upon her husband’s shoulder, a pretty young woman murmured the few lyrics she remembered of the romantic song and sank a little lower in her seat.

Her voice stopped as she felt him tense and she lifted her head in surprise.

‘Tom,’ she began. ‘What is it?’

A frown had creased the man’s forehead and he hastily switched off the radio.

‘Ssshh!’ he said. ‘Hazel, did you hear that?’

Disconcerted, the woman listened for a moment.

‘Sounds all right to me,’ she answered. ‘Probably something rattling around in the boot.’

‘I’m not talking about the car,’ he said sharply.

‘What then?’

‘Outside.’

Hazel brushed the hair from her eyes and stared at him in astonishment. Her husband was doubled over the steering-wheel, gazing up through the windscreen at the pitch black sky, scanning it fearfully.

‘Tom,’ she ventured.

‘There isn’t anything.’

‘There is!’ he said emphatically. ‘Hazel, it was weird – sort of screaming.’

She shifted on the seat and folded her arms as she began to look out of her window at the dark countryside passing by.

‘What...?’ she began nervously. ‘Like a person? That kind of screaming?’

‘There was more than one,’ came his muddling answer. ‘But it wasn’t quite human – it… it was weird.’

‘Oh, well,’ she breathed with relief, ‘if it wasn’t human...’

The golden glow of Glastonbury’s street-lamps was now clear in the distance, with the majestic outline of the Tor rearing behind them – another ten minutes and she could be in bed.

The car had been steadily picking up speed and now the woman noticed for the first time the beads of perspiration glistening upon her partner’s face.

‘Tom,’ she said. ‘Slow down. There’s black ice all over these roads.’

‘We’ve got to get home, Hazel!’ he told her and the urgency in his voice was startling. ‘We’ve got to get home, and fast! It’s too open here. I don’t like it.’

Before she could respond, something tapped lightly upon the windscreen. It was only a twig but Tom’s reaction to it was surprising.

‘Where’d that come from?’ he demanded, his voice rising with mounting panic.

The woman gaped at him in disbelief. ‘Where d’you think it came from?’ she laughed. ‘It’s a twig! Please, Tom, slow down.’

‘There are no trees on this stretch of road,’ he replied gravely.

Bewildered, Hazel threw her head back. ‘The wind blew it, a bird dropped it – I don’t know! I don’t care – but you’re driving too fast. Listen to me!’

But Tom hardly heard her. All his senses were focused upon the road ahead, yet not one of them prepared him for what happened next.

From the night it tumbled, out of the blind heavens it dropped – hurtling down with ferocious force and by the time he saw it, it was too late.

Into the bright light of the headlamps it fell – a monstrous, massive bough. Raining insanely out of the sky, the mighty limb of ancient oak came plummeting towards them.

With a tremendous, violent crunch of metal, the huge branch slammed into the bonnet of the car and the windscreen shattered into a million tiny cubes.

Screaming, Hazel threw her arms before her face as the vehicle bucked and shuddered beneath the vicious impact, and she braced herself as the tyres skidded upon the icy road.

His face scored by the twigs which had come whipping and flailing in through the splintered window, Tom gripped the wheel tightly and struggled for control as the vehicle shot into a wild, careering spin. But the windscreen was utterly blocked and all he could do was shout to Hazel to hold on.

‘NO!’ the woman yelled, clinging to him frantically as the car flew across the road and burst through the hedgerow. Into a field it thundered, with the branch still wedged upon the bonnet, and over the frozen furrows it charged.

Then, with a lurch, the spin ended and after one final jolt, the terrifying madness was over.

Gingerly, Hazel unfastened her seat belt and reached across to Tom. His hands were still clenched about the wheel and, when she held him, she discovered that he was shaking as much as herself.

Neither one of them spoke, both pairs of eyes were fixed upon the enormous branch that had dropped so unexpectedly and so illogically from above.

‘It might have killed us,’ she whispered, apprehensively reaching out to touch the rough, glassstrewn wood. ‘But where...? Where did it come from?’

Tom made no reply, his heart was pounding in his chest and his eyes widened as he stared upwards.

‘My God...’ he whimpered.

This time Hazel heard it too and her hands clasped tightly about his.

High above them the sky was filled with a terrible yammering, a foul screeching cacophony that grew louder with every awful instant.

‘The engine!’ Hazel cried. ‘Tom, start the engine – quickly!’

Her partner fumbled with the ignition but the car merely coughed pathetically whilst, overhead, the dreadful shrieks mounted steadily.

Down the nightmares swooped, bawling and squawking at the top of their voices – down to where the puny chariot struggled in the frozen mire. They crowed their hideous delight at the prospect which awaited them.

‘Lock the doors!’ Tom cried. ‘Don’t let it inside.’

‘But what is it?’

‘I don’t know!’

Screwing up his face, he tried the key again and the engine turned over.

But it was too late. With a great down-draught and a clamour of high screeching voices, they were caught. There came the beating of gigantic wings and the roof buckled as large dents were punched in the metal beneath the weight of many descending objects.

Then the enormous branch was flicked from the bonnet as easily as if it were a piece of straw. The yammering was deafening now and Hazel’s own voice joined it as she let loose a desperate scream.

Into the car, curving under the roof, there came a great and savage claw which gripped the contorted metal and the vehicle was shaken violently.

A piercing clamour ensued as the vehicle was punctured and talons stronger than steel began to rend and rip. Like a tin of peaches the car was opened, until the two stricken occupants were staring straight up through the torn, jagged rents and knew that their deaths had come.

For a moment, as they were seized and dragged into the upper airs, Tom’s and Hazel’s scream’s equalled the vile, raucous laughter of the foulness which had captured them.

Then the two human voices were silenced and, once the feast was over, the night was disturbed only by a slow, contented flapping as dark, sinister shapes took to the air.

Across the Somerset levels all was peaceful again, except for one remote field just outside Glastonbury, where the engine of an empty, wrecked car chugged erratically and the radio played soft, romantic melodies.

A force dormant for centuries was loose once more – the first of the Twelve were abroad and in the days that were to follow their numbers would increase.

Over the East End of London a bright moon gleamed down upon the many spires of the strange, ugly building known as The Wyrd Museum. But below the sombre structure’s many roofs, its cramped concrete-covered yard was illuminated by a harsher, more livid light.

Bathed in glorious bursts of intense purple flame, the enclosed area flared and flickered. With every spark and pulse, the high brick walls leapt in and out of the shadows and everything within danced with vibrant colour.

Lovingly arranged around a broken drinking-fountain, a new tribute of withered flowers appeared to take on new life once more as the unnatural, shimmering barrage painted them with vivid hues of violet and amethyst.

Yet behind the first floor windows, the source of the lustrous display was already waning as the last traces of a fiery portal guttered and crackled until, finally, the room beyond was left in darkness. Then a child’s voice began to wail and a light was snapped on.

The Separate Collection and everything it had housed were almost completely destroyed. Vicious smouldering scars scored the oak panelling of the walls, blasted and ripped by blistering bolts of energy that had shot from the centre of the whirling gateway.

Yet, from those sizzling wounds, living branches had sprouted and now the room resembled a clearing in a forest, for a canopy of new green leaves sheltered those below from the harsh electric glare of the lights and dappled them in a pleasant verdant shade.

Neil Chapman was drained and weary. His mind was still crowded with images of the past and the frightening events he had witnessed there.

Together with a teddy bear in whose furry form resided the soul of an American airman, he had been sent back to the time of the Second World War to recapture Belial – a demon that had escaped from the museum. This harrowing task they had eventually achieved, but Ted had not returned to the present and the boy didn’t know what had happened to him.

Now, all he wanted to do was leave this peculiar, forbidding room and surround himself with ordinary and familiar objects. To be back in his small bedroom that was covered in football posters and sleep in a comfortable bed was what he craved above anything, and to forget forever the drone of enemy aircraft and the boom of exploding bombs.

His thoughts stirred briefly from the dark time of the Second World War to the present again, as his young brother’s cries pushed out all other considerations and both he and Brian Chapman tried to comfort him.

‘Blood and sand!’ Neil’s father spluttered, unable to wrench his eyes from the bizarre scene around him. ‘What’s been going on? Blood and sand... blood and sand.’

Standing apart from the Chapman family, Miss Ursula Webster, eldest of the three sisters who owned The Wyrd Museum, eyed the destruction with her glittering eyes, the nostrils of her long thin nose twitching as she contained her anger.

Arching her elegant eyebrows, the woman examined the wreckage that surrounded her. All the precious exhibits were strewn over the floor, jettisoned from their splintered display cabinets, and she sucked the air in sharply between her mottled teeth.

‘So many valuable artefacts,’ her clipped, crisp voice declared. ‘It is an outrage to see them unhoused and vandalised in such a fashion.’

Turning, with glass crunching beneath her slippered heel, she clapped her hands for attention and pointed an imperious finger at Neil’s father.

‘Mr Chapman,’ she began. ‘You must begin the restoration of this collection as soon as possible. Such treasures as these must not be left lying around in this disgraceful manner. I charge you to save all you can of them, for you cannot guess their worth. My sisters and I are their custodians for a limited period only, they enjoy such shelter and guardianship as this building can offer and what slight protection our wisdom can afford.’

With a quick, bird-like movement, she turned her head to observe her two wizened sisters who were stooping and fussing over a young girl, then returned her glance to Neil’s father.

‘Mine is a grave responsibility,’ she informed him. ‘See to it that you obey me in this. When you have cleared away the rubble and removed this ridiculous foliage from the walls, throw nothing away. I must inspect everything prior to that, do you understand? We cannot afford to make another mistake.’

Brian Chapman nodded and the elderly woman gave him a curt, dismissive nod before returning to her sisters.

Miss Celandine Webster, with her straw-coloured hair hanging in two great plaits on either side of her over-ripe apple face, was grinning her toothiest smile. At her side Miss Veronica was trilling happily, her normally white-powdered countenance a startling waxy sight, covered as it was by a thick layer of beauty cream.

Edie Dorkins, the small girl brought from the time of the Blitz to the present by the power of the Websters, took little notice of them or the Chapmans. She was staring at a large piece of broken glass propped against the wall and gazing at her reflection. Upon her head the green woollen pixie-hood, a gift from the sisters, sparkled as the light caught the strands of silver tinsel woven into the stitches and she preened herself with haughty vanity.

‘Doesn’t she look heavenly?’ Miss Celandine cooed in delight. ‘And there was I worrying about the size – why it’s perfect! It is, it is!’

Leaning upon her walking cane, Miss Veronica bent forward to touch the woollen hood and sighed dreamily. ‘Now there are four of us. It’s been so long, so very, very long.’

‘Edith!’

Miss Ursula’s commanding voice rapped so sharply that the girl stopped admiring herself and fixed her almond-shaped eyes upon the eldest of the Websters.

Picking her way through the debris, Miss Ursula took the youngster’s grubby hand in her own.

‘I have said that you are to be our daughter, Edith, dear, the offspring which was denied to us and you have accepted. But do you comprehend the nature of the burden you have yoked upon your shoulders?’

An impudent grin curved over the child’s face as she stared up at Miss Ursula. ‘Reckon I do,’ she stated flatly.

The fragment of a smile flitted across the woman’s pinched features but her bony fingers gripped Edie’s hand a little tighter and when she next spoke her voice was edged with scorn.

‘Wild infant of the rambling wastes!’ she cried. ‘Akin to us you may be and many draughts of the sacred water have you drunk, but do not think you know us yet, nor the tale of all our histories.’

But Edie was not cowed by the vehemence of the old woman’s words and, baring her teeth, snapped back. ‘So teach me ’em! Tell me about the sun, the moon an’ the name of everything what grows. What has been – an’ all of whatever will be.’

Miss Ursula loosened her grip and her eyelids fluttered closed as she breathed deeply. ‘Well answered Edith, my dear – tomorrow we shall begin your instruction.’

‘No,’ the girl insisted. ‘Start now!’

Miss Ursula studied her, then gave a grim laugh. ‘Come with me!’ she cried. ‘As this is the hour of your joining with us, it is only fitting that you are shown our greatest treasure at once.’

With her gown billowing around her, Miss Ursula strode swiftly from The Separate Collection and Edie Dorkins, her eyes dancing with an excited light, ran after her.

‘Where is Ursula taking our new sister?’ Miss Veronica asked in bewilderment. ‘There’s jam and pancakes upstairs, I prepared them myself. You don’t think they’ll eat them all do you, Celandine? Do you suppose they’ll leave some for me? I love them so dearly.’

Miss Celandine’s nut-brown face crinkled with impatience as she stared after the figures of Miss Ursula and the girl as they disappeared into the darkness of the rooms beyond.

‘You and your pancakes!’ she snorted petulantly. ‘I’m certain little Edith can eat as many as she likes of them – and most welcome she is too...’ Her chirruping voice faded as her rambling mind suddenly realised where the others were going and she threw her hands in the air in an exclamation of joy and wonder.

‘Of course!’ she sang, hopping up and down, her plaits swinging wildly about her head. ‘Ursula will take her there! She will! She will – I know it – I do, I do! Oh, you must hurry, Veronica, or we may be too late.’

And so, bouncing in front of her infirm sister like an absurd rabbit, Miss Celandine scampered from the room and Miss Veronica hobbled after.

Alone with his sons, the dumbfounded Mr Chapman pinched the bridge of his nose and gazed around forlornly.

‘I... I don’t understand,’ he murmured, staring up at the spreading branches overhead. ‘I want to, but I don’t. Neil – what happened here?’

The boy pulled away from him, but he was too exhausted to explain. ‘It’s over now, Dad,’ he mumbled wearily. ‘That’s all that matters. Josh and me are safe. We’re back.’

‘Back from where? Who was that scruffy kid? She looked like some kind of refugee.’

But if Brian Chapman was expecting any answers to his questions he quickly saw that none were forthcoming. Neil’s face was haggard and his eyelids were drooping. Remembering that it was past three in the morning, the caretaker of The Wyrd Museum grunted in resignation and lifted Josh into his arms.

‘I’d best get the pair of you to bed,’ he said. ‘You can tell me in the morning.’

Neil shambled to the doorway but paused before leaving. Casting his drowse-filled eyes over the scattered debris of The Separate Collection, he whispered faintly ‘Goodbye Ted, I’ll miss you.’

Down the stairs Miss Ursula led Edie, down past a great square window through which a shaft of silver moonlight came slanting into the building, illuminating the two rushing figures.

‘Are you ready Edith, my dear?’ the elderly woman asked, her voice trembling with anticipation when they reached the claustrophobic hallway at the foot of the staircase. ‘Are you prepared for what you are about to see?’

The girl nodded briskly and whisked her head from left to right as she looked about her in the dim gloom.

The panelling of the hall was crowded with dingy watercolours. A spindly weeping fig dominated one corner, whilst in another an incomplete suit of armour leaned precariously upon a rusted spear.

‘Here... here we are,’ Miss Ursula murmured, a little out of breath. ‘At the beginning of your new life. The way lies before you, let us unlock the barrier and step down into the distant ages – to a time beyond memory or record.’

Solemnly, she stepped over to one of the panels and rapped her knuckles upon it three times.

‘I used to have to recite a string of ludicrous words in the old days,’ she explained. ‘But eventually a trio of knocks seemed to suffice. This place and I know one another too well to tolerate that variety of nursery rhyme nonsense.’

Striding back to Edie, she turned her to face the far wall then placed her hands upon the young girl’s shoulders and whispered sombrely in her ear. ‘Watch.’

Edie stared at the moonlit panels and waited expectantly as, gradually, she became aware of a faint clicking noise which steadily grew louder behind the wainscoting. Out into the hallway the staccato sound reverberated until it abruptly changed into a grinding whirr and, with an awkward juddering motion, a section of the wall began to shift and slide into a hidden recess.

‘The mechanism is worn and ancient,’ Miss Ursula confessed, eyeing the painfully slow, jarring movements. ‘In the last hundred years I have used it only seldom. Come, you must see what it has revealed.’

Edie darted forward and gazed into the shadowy space that had been concealed behind the panel.

The dusty tatters of old, abandoned cobwebs were strung across it but in a moment she had cleared them away and, with filaments of grimy gossamer still clinging to her fingers, she found herself looking at a low archway set into an ancient wall.

Tilting her head to one side and half closing her eyes, Edie thought it resembled the entrance to an enchanted castle and tenderly ran her hands over the surface of the roughly hewn stone.

‘Here is the oldest part of the museum,’ Miss Ursula’s hushed voice informed her. ‘About this doorway, whilst my sisters and I withered with age – enduring the creeping passage of time, the rest of the building burgeoned and grew. This was the earliest shrine to house the wondrous treasure of the three Fates. We are very near now, very near indeed. What can you sense, Edith? Tell me, does it call to you?’

The girl stood back and studied the wooden door that was framed by the arch. Its stout timbers were black with age and although they were pitted and scarred by generations of long dead woodworm, they were as solid as the stone which surrounded them. Into the now steel-hard grain, iron studs had once been embedded, but most of them had flaked away with the centuries, leaving only sunken craters behind. The hinges, however, were still in place and Edie’s exploring fingertips began to trace the curling fronds of their intricate design, until her hands finally came to rest upon a large, round bronze handle.

At the bottom of the door there was a wide crack where the timbers had shrunk away from the floor and a draught of cold, musty air blew about the child’s stockinged legs – stirring the shreds of web that were still attached to her.

Edie wrinkled her nose when the stale air wafted up to her nostrils, but the sour expression gradually faded from her puckish face and she took a step backwards as the faint, mouldering scent entwined around her.

The smell was not entirely unpleasant, there was a compelling sweetness and poignancy to it, and she was reminded of the roses that had been left to grow tall and wild in the gardens of bombed-out houses – their blooms rotting on the stem.

She had adored the wilderness of the bombsites. In the time of the Blitz, the shattered wasteland had been her realm and of all the fragrances which threaded their way over the rubble, the spectral perfume of spoiling roses had been her favourite.

The tinsel threads woven into her pixie-hood glittered for a moment as the haunting odour captivated her and, watching her reactions, Miss Ursula smiled with approval.

‘Yes,’ she murmured. ‘I see that you do sense it. Nirinel is aware of you, Edith, and is calling. If I needed any further proof that you were indeed one of us, then it has been provided.’

Crossing to the corner where the armour leaned against the panels, she lit an oil lamp which stood upon a small table and returned with it to Edie. Within the fluted glass of the lamp’s shade, the wick burned merrily and its soft radiance shone out over the elderly woman’s gaunt features, divulging the fact that she was just as excited as the child.

Then, with her free hand, Miss Ursula took from a fine chain about her neck a delicate silver key but, before turning it in the lock, she hesitated.

‘Now,’ she uttered gravely, ‘you will learn the secret which my sisters and I have kept and guarded these countless years, the same burdensome years that robbed us of our youth and which harvested their wits.

‘No one except we three have ever set foot beyond this entrance. Prepare yourself, Edith, once you have beheld this wonder there can be no returning. No mortal may gaze upon the secret of the Fates. Your destiny will be bound unto it forever.’

Without taking her silvery blue eyes from the doorway, the girl said simply, ‘Open it.’ Then she held her breath as Miss Ursula grasped the handle and pushed.

There came a rasping crunch of rusted iron as slowly, inch by inch, the ancient door swung inwards.

At once the stale air grew more pungent, yet Edie revelled in it. Holding the lamp aloft, Miss Ursula ducked beneath the low archway.

The darkness beyond dispersed before the gentle flame, revealing a narrow stone passageway which was just tall enough to allow the elderly woman to stand.

‘Have a care, Edith,’ Miss Ursula warned. She lowered her hand so that the light illuminated the ground and showed it to be the topmost step of a steep flight which plunged down into a consumate blackness.

‘This stair is treacherous,’ she continued, her voice echoing faintly as she began to descend. ‘The unnumbered footfalls of my sisters and I have rendered each step murderously smooth. In places they are worn completely and have become a slippery, polished slope.’

Down the plummeting tunnel Miss Ursula went, the cheering flame of the lamp bobbing before her and, keeping her cautious eyes trained upon the floor, Edie Dorkins followed closely behind.

Deep into the earth the stairway delved, twisting a spiralling path beneath the foundations of The Wyrd Museum. Occasionally, the stonework was punctuated by large slabs of granite.

At one point a length of copper pipe, encrusted with verdigris, projected across the tunnel and Miss Ursula was compelled to stoop beneath it.

‘So do the roots of the modern world reach down to the past,’ she remarked. ‘Yet, since the well was drained, no water flows from the drinking-fountain above.’

Pressing ever downwards, she did not utter another sound until she paused unexpectedly – causing Edie to bump into her.

‘At this place the outside presses its very closest to that which we keep hidden,’ she said, bringing the lamp close to the wall until the young girl could see that large cracks had appeared in the stones.

‘A few feet beyond this spot lies one of their tunnels. A brash and noisome worm-boring, a filthy conduit to ferry people from one place to another like so many cattle. Perilously near did their excavations come to finding us. Now, when the carriages hurtle through that blind, squalid hole, this stairway shakes as though Woden himself had returned with his armies to do battle one last time.’

Miss Ursula’s voice choked a little when she said this. Edie looked up at her in surprise but the elderly woman recovered quickly.

‘It is most inconvenient,’ her normal clipped tones added. ‘Thus far they have not discovered us, yet a day may come perhaps when these steps are finally unearthed by their over-zealous probing. What hope then for the unhappy world? If man were to know of the terrors which wait to seize control of his domain he would undoubtedly destroy it himself in his madness. That is what we must save them from, Edith. They must never know of us and our guardianship.’

Her doom-laden words hung on the cold air as she turned to proceed.

‘Still,’ she commented dryly, ‘at least at this hour of the night there are no engines to rumble by and impede our progress.’