Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

Kitabı oku: «All My Sins Remembered», sayfa 3

Two

‘My mother was a Holborough, you know,’ Clio said.

Elizabeth did know. She also knew that Clio’s grandmother had been Miss Constance Earley, who had married Sir Hubert Holborough, Bt, of Holborough Hall, Leicestershire, in 1875. Her daughters had been born in April 1877.

Lady Holborough never fully recovered from the stress of the twin pregnancy and birth, and she lived the rest of her life as a semi-invalid. There were no more children. Blanche and Eleanor Holborough spent their childhood in rural isolation in Leicestershire, best friends as well as sisters.

Elizabeth knew all this, and more. She had the family diaries, letters, Bibles, copies of birth and death certificates, the biographer’s weight of bare facts and forgotten feelings from which to flesh out her people. She thought she knew more about the history of their antecedents than Clio had ever done, and Clio had forgotten so much. Clio could not even remember what they had talked about last time they met.

And yet Clio possessed rare pools of memory in which the water was so clear that she could stare down and see every detail of a single day, a day that had been submerged long ago by the flood of successive days pouring down upon it. Elizabeth wanted to lean over her shoulder and look into those pools too. That was why she came to sit in this room, with her miniature tape-recorder and her notebook, to look at reflections in still water.

‘A Holborough. Yes,’ Elizabeth said.

‘Mother used to tell me stories about when she was a little girl.’

When Blanche and Eleanor were girls, a hundred years ago.

‘What sort of stories?’

Clio gave her cunning look, to show that she was aware of the eagerness behind the question. ‘Stories …’ she said softly, on an expiring breath.

There was a silence, and then she began.

‘Holborough was a fine house. Not on the scale of Stretton, of course, but it was the first house in the neighbourhood. There was a maze in the gardens. Mother and Aunt Blanche used to lead new governesses into it and lose them. They knew every leaf and twig themselves. They would slip away and leave the poor creatures to wander all the afternoon. Then the gardeners would hear the pitiful cries, and come to the rescue.’

Elizabeth had visited Holborough Hall. After it had been sold in the Twenties it had been a preparatory school and then in wartime a training camp for Army Intelligence officers. After the war it had stood empty, and then seen service as a school again. Lately it had become a conference centre. The famous maze had survived, just. It looked very small and dusty, marooned in a wide sea of tarmac on which delegates parked their cars.

‘Can’t you imagine them?’ Clio was saying. ‘Identical little girls in pinafores, whisking gleefully and silently down the green alleys?’

Elizabeth smiled. ‘Yes, I can imagine.’

‘They had to make their own amusements. There were no other children. It wasn’t like it was for me, living in the middle of Oxford, with brothers and cousins always there.’

But it had been a happy childhood, Clio knew that, because Eleanor and Blanche often spoke of it. There had been carriage drives and calls with their mother, when she was well enough. There had been outings in winter to follow the hunt, with their father’s groom. Sir Hubert was an expert horseman. There had even been visits to London, to shop and to visit Earley relatives. There had been nannies and governesses and the affairs of the estate and the village. But most importantly of all, there had been the private world that they had created between them.

It was a world governed only by their imaginations, a mutual creation that released them from the carpet-bedded gardens and the crowded mid-Victorian interiors of Holborough, and set them free. They made their own voyages, their own discoveries, even spoke their own language. The intimacy of it lasted them all their lives, even when the intricate games were long forgotten.

Their imaginary world of play was put aside, reluctantly, when the real world judged that it was time for them to be grown up. Blanche and Eleanor accepted the judgement obediently, because they had been brought up to do as they were told, but they kept within themselves a component that remained childlike, together.

Eleanor’s husband Nathaniel thought it was this buried streak of childishness that gave them their air of unconventionality buttoned within perfect propriety. He found it very alluring.

When the twins reached the age of seventeen, Sir Hubert and Lady Holborough decided that their daughters must do the Season. Constance had been presented at Court as a débutante, and in the same year she had been introduced to and then become engaged to Hubert. There had been little Society or London life for her in the years afterwards, because of her own ill-health and her husband’s addiction to field sports, but they were both agreed that there was no reason to deny their daughters their chances of a good marriage.

Constance was apprehensive, and her nervousness took the form of vague illness. But still, a house was taken in Town, and more robust and cosmopolitan Earley aunts were enlisted to launch their nieces into Society.

The twins brought few material or social advantages with them to London in 1895. Their father was a baronet of no particular distinction, except on the hunting field. Their mother came from an old family and had been a beauty in her day, but she had not been much seen for more than fifteen years. There was no great fortune on either side.

But still, against the odds, perhaps because they didn’t care whether they were or not, the Misses Holborough were a success.

They were not beautiful. They had tall foreheads and narrow, too-long noses, but they had handsome figures and large dark eyes and expressive mouths that often seemed to register private amusement. Nathaniel Hirsh was not the first man to be attracted by their obviously enjoyable unity in an exclusive company of two. They began to be invited, and then to be courted. Young men joked about declaring their love to a Miss Holborough on one evening, and then discovering on the next that they had fervently reiterated it to the wrong one.

The joke was more often Blanche and Eleanor’s own. It amused them to tease. From infancy they had used their likeness to play tricks on nannies and governesses, and it seemed natural to extend the game to their dancing partners. They wore one another’s gowns and exchanged their feathered headdresses, became the other for a night and then switched back again. They acquired a reputation for liveliness that added to their appeal.

One evening towards the end of the Season there was a ball at Norfolk House. Blanche and Eleanor had received their cards, and because Lady Holborough was unwell they were chaperoned by Aunt Frederica Earley. Sir Hubert escorted them, although he had no patience with either dancing or polite conversation. He was anxious for the tedium of parading his daughters through the marriage market to be over and done with, so he could return home to Leicestershire and his horses. He had already announced to his wife that he considered the whole affair to be a waste of his time and his money, since neither girl showed any inclination to choose a husband, or to do anything except whisper and giggle with her sister.

The Duchess’s ballroom was crowded, and the twins were soon swept into the dancing. Their aunt, having married her own daughters, was free to watch them with proprietary approval. Blanche was in rose pink and Eleanor in silver. They looked elegant and they moved gracefully. They had no particular advantages, the poor lambs, but they would do. Mrs Earley was not worried about them.

She was not the only onlooker who followed the swirls of rose pink and silver through the dance.

There was an urbane-looking gentleman at the end of the room who watched the mirror faces as they swung, and smiled, and swung again. The room was full of reflections but these were brighter; their images doubled each other until the ballroom seemed full of dark hair and assertive noses and cool, interrogative glances.

The gentleman inclined his head to one of the ladies who sat beside him. ‘Who are they?’ he asked.

The woman fastened a button at the wrist of her long white glove.

‘They are the Misses Holborough,’ she answered. ‘Twins,’ she added unnecessarily, and with a touch of disapproval in her voice that made it sound as if it was careless of them.

‘They are interesting,’ the man said. ‘Do you know their family?’

‘The lady in blue, over there, is their aunt. Mrs Earley. I am acquainted with her. Their mother is an invalid, I believe, and their father is a bore. I would be happy to give you any more information, if I possessed it.’

The man laughed. His companion had daughters in the room who were not yet married and who were much less intriguing than the Misses Holborough. He asked, ‘And may I be presented to Mrs Earley?’

A moment later, he was bowing over another gloved hand.

‘Mr John Singer Sargent,’ Mrs Earley’s acquaintance announced.

‘I should very much like to paint your nieces, Mrs Earley,’ the artist said.

Mrs Earley was flattered, and agreed that it was a charming idea, but regretted that the suggestion would have to be put to Sir Hubert, her brother-in-law. When Sir Hubert re-appeared in the ballroom he was still smarting from the loss of fifty-six guineas at a friendly game of cards, and he was not in a good humour. Fortunately Mr Sargent had moved away, and was not in the vicinity to hear the response to his proposal.

Sir Hubert said that he couldn’t imagine what the fellow was thinking of, wanting him to pay some no doubt colossal sum for a pretty portrait of two silly girls who had never had a sensible thought in their lives. The answer was certainly not. It was a piece of vanity, and he wanted to hear no more about it.

‘You make yourself quite clear, Hubert,’ Mrs Earley said, pressing her lips together. No wonder Constance was always indisposed, she thought.

The ball was over. Blanche and Eleanor presented themselves with flushed cheeks and bright eyes and the pleasure of the latest tease reverberating between them. The Holboroughs’ carriage was called and the party made its way home, to Sir Hubert’s obvious satisfaction.

The end of the Season came. The lease on the town house ran out and the family went back to Holborough Hall. Blanche and Eleanor were the only ones who were not disappointed by the fact that there was no news of an engagement for either of them. They had had a wonderful time, and they were ready to repeat the experience next year. They had no doubt that they could choose a husband apiece when they were quite ready.

The autumn brought the start of the hunting season. For Sir Hubert it was the moment when the year was reborn. From the end of October to the beginning of March, from his estate outside the hunting town of Melton Mowbray, Sir Hubert could ride to hounds if he wished on six days of every week. There were five days with the Melton packs, the Quorn, the Cottesmore and the Belvoir, and a sixth to be had with the Fernie in South Leicestershire. There were ten hunters in the boxes in the yard at Holborough for Sir Hubert and his friends, and a bevy of grooms to tend them and to ride the second horses out to meet the hunt at the beginning of the afternoon’s sport.

The hall filled up with red-faced gentlemen whose conversation did not extend beyond horses and hunting. They rode out during the day, and in the evenings they ate and drank, played billiards, and gambled heavily.

Now that they were out, Blanche and Eleanor were expected to join the parties for dinner. They listened dutifully to the hunting talk, and kept their mother company after dinner in the drawing room, while the men sat over their port or adjourned to the card tables in the smoking room.

‘Is this what it will be like when we are married?’ Blanche whispered, trying to press a yawn back between her lips.

‘It depends upon whom we marry, doesn’t it?’ Eleanor said, with a touch of grimness that was new to her.

Then one night there was a new guest at dinner, a little younger and less red-faced than Sir Hubert’s usual companions. He was introduced to the Holborough ladies as the Earl of Leominster.

They learnt that Lord Leominster lived at Stretton, in Shropshire, and that he also owned a small hunting box near Melton. The house was usually let for the season, but this year the owner was occupying it himself with a small party of friends. Sir Hubert and his lordship had met when they enjoyed a particularly good day out with the Quorn and, both of them having failed to meet their grooms at dusk, they had hacked part of the way home together.

Lord Leominster had accepted his new friend’s invitation to dine.

On the first evening, Eleanor and Blanche regarded him without much favour. John Leominster was a thin, fair-skinned man in his early thirties. He had a dry, careful manner that made an odd contrast with the rest of Sir Hubert’s vociferous friends.

‘Quiet sort of fellow,’ Sir Hubert judged. ‘Can’t tell what he’s thinking. But he goes well. Keen as mustard over the fences, you should see him.’

Lady Holborough quickly established that his lordship was unmarried.

‘Just think, girls,’ she whispered. ‘What a chance for one of you. Stop smirking, Eleanor, do. It isn’t funny at all.’

The girls rolled their eyes at each other. Lord Leominster seemed very old and hopelessly shrivelled from their eighteen-year-old standpoint. They were much more interested in the cavalry officers from the army remount depot in Melton.

But it soon became clear that the twins had attracted his attention, as they drew everyone else’s that winter. Against the brown setting of Holborough they were as exotic and surprising as a pair of pink camellias on a February morning. After the first dinner he called again, and then became a regular visitor.

It was also evident, from the very beginning, that he could tell the two of them apart as easily as their mother could. There were no mischievous games of substitution. Eleanor was Eleanor, and Blanche was the favoured one.

John Leominster became the first event in their lives that they did not share, did not dissect between them.

Eleanor was startled and hurt, and she took refuge in mockery. She called him Sticks for his thin legs, and before she spoke she cleared her throat affectedly in the way that Leominster did before making one of his considered pronouncements. She made sure that Blanche saw his finicky ways with gloves and handkerchiefs, and waited for her sister to join her in the mild ridicule. But Blanche did not, and they became aware that a tiny distance was opening between them.

Blanche was torn. After the first evening she felt guilty in not responding to Eleanor’s overtures, but she began to feel flattered by the Earl of Leominster’s attention. She was also surprised to discover how pleasant it was to be singled out for herself alone, instead of always as one half of another whole. As the days and then the weeks passed, she was aware of everyone in the household watching and waiting to see what would happen, and of Constance almost holding her breath. She saw her suitor’s thin legs and fussy manners as clearly as her sister did, but then she thought, The Countess of Leominster …

One night Eleanor asked impulsively, ‘What are you going to do, Blanche? About Sticks, I mean?’

‘Don’t call him that. I can’t do anything. I have to wait for him to offer, don’t I?’

Eleanor stared at her. Until that moment she had not fully understood that her sister meant to accept him if he did propose marriage.

‘Oh, Blanchie. You can’t marry him. You don’t love him, do you?’

Blanche pulled out a long ringlet of hair and wound it round her forefinger. It was a characteristic mannerism, familiar to Eleanor from their earliest years. ‘I love you,’ Eleanor shouted. ‘I won’t let him take you away.’

‘Shh, Ellie.’ Blanche was deeply troubled. ‘We both have to marry somebody, someday, don’t we? If I don’t love him now, I can learn to. He’s a kind man. And there’s the title, and Stretton, and everything else. I can’t turn him down, can I?’

Eleanor shouted again. ‘Yes, you can. Neither of us will marry anyone. We’ll live together. Who needs a husband?’

Slowly, Blanche shook her head. ‘We do. Women do,’ she whispered.

Eleanor saw that her sister was crying. There were tears in her own eyes, and she stood up and put her arms round Blanche. ‘Go on, go on then. Make yourself a Countess. Just have me to stay in your house. Let me be aunt to all the little Strettons. Just try to stop me being there.’

Blanche answered, ‘I won’t. I never would.’

They cried a little, shedding tears for the end of their childhood. And then, with a not completely disagreeable sense of melancholy, they agreed that they had better sleep or else look like witches in the morning.

There came the evening of an informal dance held in the wooden hall of the village next to Holborough. The twins dressed in their rose pink and silver, and sighed that Beecham village hall was a long way from Norfolk House. But there was a large contingent of whooping army officers at Beecham, and there was also John Leominster. While Eleanor was passed from arm to arm in the energetic dancing, Blanche agreed that she would take a respite from the heat and noise, and stroll outside the hall with her partner.

Lady Holborough inclined her head to give permission as they passed the row of chaperones, and Blanche knew that all their eyes were on them as they passed out into the night. It was a mild evening, but she drew her fur wrap tightly around her shoulders like a protective skin. She was ready, but she was also afraid. They walked, treading carefully over the rough ground.

‘Blanche, you know that I would very much like you to see Stretton, and to introduce you to my mother.’

Blanche inclined her head, but she said nothing.

John cleared his throat. She was irresistibly reminded of Eleanor’s mimicry, but she made herself put Eleanor out of her mind, and concentrate on what was coming. It was, she knew, the most important moment of her life. If it seemed disappointing that it should have come now, outside the barn-like hall at the end of a rutted country lane, then she put her disappointment aside and waited.

‘I think you know what I want to say to you. Blanche, my dear, will you marry me?’

There was nothing more to wait for. There it was, spoken.

‘Yes, John. I will,’ Blanche said. Her voice sounded very small.

He stopped walking and took her in his arms. His lips, when they touched hers, were soft and dry and they did not move. That seemed to be all there was.

‘I shall speak to your father in the morning,’ John said. He took her hand and they turned to walk back towards the hall. ‘You make me very happy,’ he said.

‘I’m glad,’ Blanche answered.

After the engagement was announced, his lordship seemed to become aware of the bond between his fiancée and her twin sister. It was as if he could safely acknowledge its existence, now that he had made sure of Blanche for himself. He reminisced about how he had first seen them, coming arm in arm into the drawing room at Holborough.

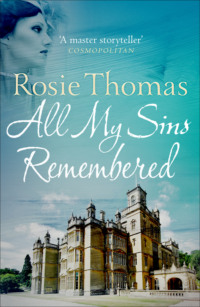

‘As lovely as a pair of swans on a lake,’ he said, surprising them with a rare verbal flourish. Blanche smiled at him, and he put his hand on her arm. He took the opportunity to tell the sisters he wished to have their portrait painted. The double portrait would mark his engagement to Blanche, but it would also celebrate the Misses Holborough. He had already chosen the artist. It was to be Sargent.

When the spring came, Lady Holborough and her daughters removed to London. Blanche’s wedding clothes and trousseau needed to be bought, and there were preparations to be made for Eleanor’s second Season. They settled at Aunt Frederica Earley’s house, and in the intervals between shopping and dressmakers’ appointments the twins presented themselves for sittings at Mr Sargent’s studio.

They enjoyed their afternoons with the painter. He had droll American manners, he made them laugh, and he listened with amusement to their talk.

The portrait, as it emerged, reflected their rapport.

The girls were posed on a green velvet-padded love seat. Blanche faced forwards, dressed in creamy silk with ruffles of lace at her throat and elbows. Her head was tilted to one side, as if she was listening to her sister’s talk, although her dark eyes looked straight out of the canvas. Her forefinger marked her place in the book on her lap. Eleanor faced in the opposite direction, but the painter had turned her so that she looked back over her own shoulder, her eyes following the same direction as her sister’s. Their mouths were painted as if they were on the point of curving into smiles, the eyes were bright with laughter and the dark eyebrows arched questioningly over them. Eleanor wore sky-blue satin, with a navy-blue velvet ribbon around her throat.

Their white, rounded forearms rested side by side on the serpentine back of the love seat. It was a pretty pose.

The girls looked what they were, identically young and innocent and good-humoured. There was no need for Mr Sargent to soften any of the sharpness of his vision with superficial flattery. He painted what had first attracted him in the ballroom at Norfolk House, twin images of lively inexperience.

‘You have made us look too pretty,’ Eleanor told him.

‘I have painted you as I see you,’ he answered. ‘I can do no more, and I would not wish to do less.’

‘We look happy,’ Blanche observed.

‘And so you should,’ John Sargent told her, with the advantage of more than twenty years’ longer experience of the world. ‘You should be happy.’

Even then, the girls understood that he had captured their girlhood for them on canvas, just at the point when it was ending.

The Misses Holborough was judged a success. John Leominster paid for the double portrait, and after the wedding it was transported to Stretton where it was hung in the saloon. Blanche sometimes hesitated in front of it, sighing as she passed by.

Eleanor was often at Stretton with her, but she could not always be there. Blanche missed her, but she was also occupied with trying to please her husband, and with the peculiar responsibilities of taking over from her mother-in-law as the mistress of the old house. The separation was much harder for Eleanor.

The dances and dinners of the second Season were no longer a novelty. They were also much less amusing without Blanche, who was away in Italy on her wedding journey all through the height of it. A small compensation for Eleanor was a new friendship with her cousin Mary, the younger daughter of Aunt Frederica Earley. Mary had married a languid and very handsome man called Norton Ferrier, and the Ferriers were part of a group of smart, young, well-connected couples who prided themselves on their powers of intellectual and aesthetic discrimination. They called their circle the Souls, and they spent weekends in one another’s comfortable houses in the country, reading modern poetry and writing letters and diaries and discussing art.

Mary was kind-hearted and generous, and she began to invite her young cousin to accompany Norton and herself on their weekend visits. Constance was glad to let her go, and there could be no objection to Eleanor making excursions in the company of her older married cousin.

The Souls were sophisticated and under-occupied. Once their conventional marriages had set them free, they were at liberty to wander within the limits of their miniature world and amuse themselves by falling in and out of love with one another. Most of them had one or two young children. They had done their family duty, and they left their heirs at home in their nurseries while they travelled to one another’s houses to play, and to talk, and to pursue their romantic interests. At night the corridors of the old houses whispered with footsteps. The mute family portraits looked down on the secret transpositions.

There was one house in a village near Oxford that Eleanor liked particularly. It was an ancient grey stone house, set in a beautiful walled garden. Eleanor liked to wander on her own along the stone paths, breathing in the scents and bending down to examine a leaf or a tiny flower beside her shoe. At Fernhaugh she was perfectly happy to leave the Souls to their books and their mysterious murmurings, and to enjoy herself amongst the plants.

She was, she told herself with a touch of mournful pride, learning to be by herself. And at the same time she wondered if she could persuade Blanche to begin the creation of a garden like this somewhere in the Capability Brown park at Stretton.

One Sunday morning at Fernhaugh Eleanor was walking in the garden. There had been rain overnight and the perfume was intensified by the damp air. She knew that some of the house party had dutifully gone to church to hear their host reading the lesson, but that most of the Souls were not yet downstairs. There were guests expected for luncheon, but the drawing room with the French windows looking out on the terrace was still empty. Even the gardeners would not appear today. The green enclosure in all its glory was hers alone.

Eleanor wandered, breathing in the richness, letting her fingers trail over dewy leaves and fat, fleshy petals. She felt for a moment as if she might at last aspire to the sensuous abandon of the real Souls. She let her eyes close, feeling the garden absorb her into its green heart.

From close at hand, too close, an unfamiliar voice asked, ‘Are you all right?’

Eleanor’s eyes snapped open.

She saw a man she had never met, a big man in odd black clothes made even odder-looking by his big, thick black beard. He must have come silently over the grass, although his feet looked big enough to make a clatter on any surface.

‘I am perfectly all right. Why should you think I am not?’

‘I wondered if you were going to faint. Or worse, perhaps.’

It came to her how she must have looked, drooping with closed eyes between the soaking leaves, and her face turned red.

‘Thank you, but there’s no danger of anything like that. Unless as the result of shock. From being pounced on in an unguarded moment by a perfect stranger.’

‘By a peculiar-looking person far from perfect, don’t you mean?’

The man was smiling. His beard seemed to spread around his jawline. The smile revealed his shiny mouth and healthy white teeth.

‘I don’t mean anything,’ Eleanor said, retreating from this newcomer. ‘Will you excuse me? I should go and make myself ready for luncheon.’

To her surprise, the man turned and began to walk with her across the grass towards the house. He strolled companionably with his hands behind his back, looking from side to side.

‘This garden is very beautiful,’ he said. And then, peering sideways at Eleanor with unmistakable mischief, he recited, “Sed vos hortorum per opaca silentia longe Celerant plantae virides, et concolor umbra.” Do you know the lines?’

Blanche and Eleanor’s governesses had had to negotiate too many other obstacles at Holborough. There had been little time to spare for Latin verse.

‘No,’ Eleanor said. She was thinking that the man was not such a misfit at Fernhaugh as his appearance suggested. No doubt the Souls would all be familiar with the verse, whatever it was. Or would at least claim to be.

‘No? It’s Marvell, of course. He is addressing Innocence. He finds her in the shaded silences of gardens, far off, hiding among the green plants and like-coloured shadow.’

‘Thank you so much for the translation.’ Eleanor took refuge in briskness. They had reached the terrace and the open doors of the drawing room were only a few steps away. ‘Don’t let me detain you any further in your search for Innocence amongst the rose-bushes.’

The man was smiling again, looking full into her face. He seemed very large and dark and exotic in the English summer garden. He wouldn’t let her go so easily. ‘In the absence of our hostess, may I introduce myself? I am Nathaniel Hirsh.’

‘Eleanor Holborough.’

The man’s hand enveloped hers. The grip was like a bear’s.

‘And now you must excuse me.’

Eleanor mounted the two steps to the terrace level and passed out of the sunshine into the dimness of the drawing room. Nathaniel watched her go. He was thinking with irritation that although he had been born in England, and had lived in England for most of his twenty-six years, he would never make an Englishman. He could never get the subtle nuances of behaviour quite right. He could never even get the broad principles. Today he had arrived for luncheon at least an hour too early. Then he had seen a striking girl daydreaming in the wonderful garden. An Englishman would have approached her with some stiff-necked platitude and she would have known exactly how to respond. But instead he had pounced on her with some clumsy joke. And then he had begun declaiming in Latin. Innocence amongst the green plants and like-coloured shadow, indeed.

Yet, that was how she had looked.

‘You will never learn, Nathaniel,’ he said aloud. But he was humming as he leant over and picked a yellow rose from the branch trailing over the terrace wall. He slid the stem into his buttonhole. He had liked the look of Eleanor Holborough. He had liked even better her cool admission of ignorance of Marvell’s Hortus. Nathaniel did not think many of the other guests at Fernhaugh would have acknowledged as much. He liked Philip Haugh well enough, but he did not have much patience with the rest of the crew.