Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

Kitabı oku: «The Greatest Benefit to Mankind», sayfa 18

ANATOMY

The theory and practice of Galenic medicine were under debate, but in essentials Galenism remained intact, queried by some, defied by quacks and mavericks, but challenged head-on only occasionally, notably by the Swiss iconoclast, Paracelsus (see Chapter 9). Substantial change did, however, occur in anatomy. For long but an antechamber in the palace of medicine, anatomy’s rise owed much to Renaissance artists who grew fascinated with body form and developed the representational, naturalistic techniques so conspicuous in the magnificent illustrations of sixteenth-century anatomy texts.

In his De statua (c. 1435) [On the Statue], the humanist Leon Battista Alberti (1404–1472) argued that knowledge of the bodily parts was vital for the artist, providing him with insight into human proportion which echoed the harmonies of nature and art. Lorenzo Ghiberti (d. 1455) claimed that the artist had to be proficient in the ‘liberal arts’, including perspective, drawing-theory and anatomy. Knowledge of the skeleton conferred insight into proportion in both microcosm and macrocosm. Art theory and practice emphasized the value of anatomical knowledge and hence of dissecting experience. Underlying this was a naturalistic impulse, though one with its eye on the ideal beauty glimpsed in Graeco-Roman statues. Like the literary humanists, Renaissance artists believed the ancients had observed nature best.

Painters were soon pursuing anatomy as a matter of course. Leonardo da Vinci’s teacher Andrea Verrocchio (1435—88), Andrea Mantegna (d. 1506) and Luca Signorelli (c. 1444–1524) all showed some knowledge of muscular and perhaps of deeper anatomy: Verrocchio had his pupils study flayed bodies. It was, however, da Vinci (1452–1519), Albrecht Durer (1471–1528) and Michelangelo (1475–1564) who most clearly applied the knowledge gained from anatomy.

A brilliant anatomical illustrator, Leonardo was also a perceptive investigator of the mechanics of the human body. Ironically, given the humanist creed, he had no medical education, stumbled over Latin and knew no Greek. His anatomical notebooks show him comparing anatomy with architecture, and using it to probe the mysteries of the microcosm. Although it was never fully realized, from 1489 he planned an anatomical atlas of the stages of man from womb to tomb. His earliest investigations in the late 1480s centred upon a series of skull drawings, which outclassed all previous descriptions. He prized ‘experience’, but retained a traditional view of brain functions, attributing mental activity to three ventricles governing respectively sensation, intellect, and memory. The nervous system was rendered as a series of passages through which sensations and signals ebbed and flowed.

‘Passing the night hours in the company of these corpses, quartered and flayed and horrible to behold’, it was after 1506 that Leonardo made his main anatomical contributions, devoting his attention to embryonic development, the muscles, and the nervous, vascular, respiratory and urino-genital systems. The vessels and respiratory passages were compared to the branching of trees and river valleys, and the workings of the heart explained in terms of hydrodynamics and mechanics. Leonardo executed about 750 anatomical drawings, which in some respects are superior to those in Vesalius’s Fabrica (1543), yet his thinking remained traditional. He continued to accept the Galenic doctrine that blood passed between the ventricles through invisible pores in the septum; and his drawings of the embryo were set within a ‘traditional’ womb. His career reflects the new involvement of artists with anatomy, though his work had no influence on contemporary medicine, since none of his anatomical manuscripts was published until the late eighteenth century.

As well as artists, medical men also anatomized. Among Renaissance anatomists the desire to see for oneself (the literal meaning of ‘autopsy’) arose from a variety of traditions. Berengario da Carpi (c. 1460–1530) studied at Bologna, the cradle of dissection, and in 1502 became lecturer in surgery there. He made the basis for his lectures the Anatomy of his Bolognese predecessor, Mondino, and his Introduction follows earlier procedures for public dissection. Berengario was no slavish imitator. While often using Galen to disprove Mondino, he was prepared to criticize him on the basis of personal observations, denying the existence in humans of Galen’s rete mirabile, that ‘marvellous network’ of blood vessels supposedly lying at the base of the brain (it is found in some animals but not in humans). Insisting on the need for frequent dissections, including humans, he gained a knowledge of female internal anatomy on the basis of postmortem examinations, including one of an executed pregnant woman.

The earliest truly Greek anatomical text was that of Alessandro Benedetti (d. 1512), who lived for sixteen years in Greece and Crete before returning to Padua in 1490 as professor of practical anatomy. In his Historia corporis humani; sive anatomice (1502) [The Account of the Human Body: Or Anatomy], the Greek anatomice in the title highlighted his hellenism. As a good humanist, Benedetti, like Leoniceno, weeded out Arabic terminology and self-consciously used Greek anatomical terms. Though his book was philological rather than substantive, it did provide an account of a well-ordered anatomy theatre.

Humanist anatomy was given a boost by the discovery of the first part of Galen’s On Anatomical Procedures (his treatise on how to carry out a dissection) translated into Latin by Guinther von Andernach in 1531. Mondino had started with the internal organs, since these putrefied first. His procedures were rejected by humanists in favour of Galen, who had begun in a more logical fashion with the bones – they were like the walls of houses, he wrote, everything else took shape from the skeleton – next proceeding to the muscles, nerves, veins and arteries, before reaching the cavities of the belly, the chest and the brain, and the internal organs.

But if Galen’s dissection strategy was more rational and the quality of his descriptions superior, its flaw was that it was animal not human. A challenge was thus thrown down to anatomists to outdo the master through hands-on investigation of the human corpse. The Liber introductorius anatomiae (1536) [Introductory Book of Anatomy] of the Venetian physician Niccolò Massa (c. 1485–1569) scolded those who pronounced on anatomy without having applied the knife to the things they wrote about.

By the 1520s increasing numbers of anatomical texts were being published, and Johannes Dryander (1500–60), professor of medicine at Marburg, carried out some of the first public dissections in Germany, writing these up in a treatise on the anatomy of the head. Andreas Vesalius (1514–64), however, restored Galenic anatomy in such a way as to transcend it. A true Galenic anatomist, in the sense of following the master’s advice to see for oneself, Vesalius also presented himself in his De humani corporis fabrica (1543) [On the Fabric of the Human Body] as a critic who had no compunction about exposing Galen’s errors: ‘How much has been attributed to Galen, easily leader of the professors of dissection, by those physicians and anatomists who have followed him, and often against reason!’

Born Andreas van Wesele in Brussels, where his father was pharmacist to Emperor Charles V, Vesalius learned Latin and Greek and enrolled in the Paris Faculty of Medicine, studying under the conservative humanist Sylvius, then Galen’s great champion. (In later years Sylvius became a scourge of Vesalius, wittily calling him vesanus: madman.) Vesalius learnt his dissecting skills from Guinther von Andernach, and when in 1536 war forced him to flee Paris, he returned to Louvain where he introduced dissection. He showed his anatomical zeal by robbing a wayside gibbet, smuggling the bones back home and reconstructing the skeleton.

In 1537 he moved to Padua, where he made his anatomical name. Dissection had previously been demonstrated there by surgeons, and had never been mandatory for physicians. The rediscovery of Galen’s On Anatomical Procedures and the wider dissemination of his On the Use of Parts meant that humanists were beating the drum for the subject, and the appointment of the young physician was one consequence. Vesalius’s Tabulae anatomicae sex (1538) [Six Anatomical Pictures] were among the first anatomical illustrations specifically designed for students. The first three sheets were drawn by Vesalius himself and represented the liver and its blood vessels, together with the male and female reproductive organs, the venous and the arterial system. He was still viewing the body through Galenic eyes: despite Berengario, he drew the rete mirabile; the liver was still five-lobed, and the heart an ape’s.

Thereafter Vesalius grew more critical. Familiarity with human anatomy drove him to the unsettling conclusion that Galen had dissected only animals, and forced him to see that animal anatomy was no substitute for human. He now began to challenge the master on points of detail: for instance, the lower jaw comprised a single bone not two, as Galen, relying on animals, had stated. Evidently, human anatomy had to be learned from dead bodies not dead languages.

In 1539 he acquired a larger supply of cadavers of executed criminals and worked on his great masterpiece, the De humani corporis fabrica. Finishing it in 1542, he took it to Basel where the press of Joannes Oporinus published it in 1543 as one of the pearls of Renaissance printing. It presents exact descriptions of the skeleton and muscles, the nervous system, blood vessels and viscera. Though it contains no shattering discoveries, it marks a watershed in the medical understanding of bodily structures, for Vesalius interrogated Galen by reference to the human corpse. Others had criticized odds and ends of Galenic anatomy, but Vesalius was the first to do this systematically. The Fabrica gained immensely from the contribution of the artist, Jan Stephan van Calcar (1499–c. 1546), also from the Netherlands, who provided the text with technically accurate drawings displaying the dissected body in graceful lifelike poses. The work also enunciated clear methodological principles: the anatomist-lecturer must perform the dissection himself, the eye was preferable to authority, and anatomy was the skeleton key to medicine.

Book I of the Fabrica began in Galenic fashion with the bones rather than the internal organs. Various Galenic lapses were corrected: for example, the human sternum has three, not seven, segments. Book II dealt with the muscles and included the famous suite of illustrations showing ‘muscle-men’ at different stages of corporeal ‘undress’. Book III, on the vascular system, was less accurate because Vesalius still based his descriptions partly on animal material. Book IV described the nervous system, following the Galenic classification of the cranial nerves into seven pairs.

Book V dealt with the abdominal and reproductive organs, where he corrected Galen’s belief in the five-lobed human liver. He nevertheless still accepted the Galenic physiological tenet that the liver produced blood from chyle, while denying that the vena cava originated in the liver – an observation which, had Vesalius been more physiologically-minded, might have begun the erosion of the Galenic belief in two distinct vascular systems, the venous originating in the liver and the arterial stemming from the heart.

Book VI was devoted to the thorax. Examining the heart, Vesalius cast doubt on the permeability of the interventricular septum: ‘We are driven to wonder at the handiwork of the Almighty by means of which the blood sweats from the right into the left ventricle through passages which escape the human vision.’ In the second edition (1555), this implicit denial of the septum’s permeability was made direct. Here lay a milestone of Renaissance anatomy, for it encouraged anatomists like Realdo Colombo (c. 1515–59) to conceive of the pulmonary transit, later used by William Harvey as evidence of the circulation of the blood. Another crucial correction of Galen came in Book VII, on the brain, where Vesalius denied the existence of the rete mirabile in humans.

In the end, Vesalius’s importance lay in daring to think the unthinkable: that Galen might actually be wrong, and Galen worship with it:

How much has been attributed to Galen, easily leader of the professors of dissection, by those physicians and anatomists who have followed him, and often against reason! … Indeed, I myself cannot wonder enough at my own stupidity and too great trust in the writings of Galen and other anatomists.

The Fabrica thus laid the groundwork for observation-based anatomy, announcing a new principle of fact-finding and truth-testing: all anatomical statements were to be subjected to the test of human cadavers.

Later anatomists corrected Vesalius as he had corrected Galen, and independent observation thus became sovereign. Anatomists also grew impatient to establish personal priority in discovering new structures. Amerigo Vespucci had his name immortalized in a continent; for an anatomist, naming a bodily part could be crucial for making his name.*

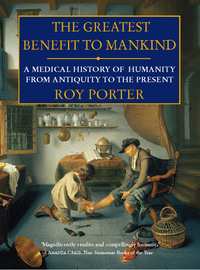

The frontispiece of the Fabrica presents the dreams, the programme, the agenda, of the new medicine. The cadaver is the central figure. Its abdomen has been opened so that everyone can peer in; it is as if death itself had been put on display. A faceless skeleton points towards the open abdomen. Then there is Vesalius, who looks out as if extending an invitation to anatomy. Medicine would thenceforth be about looking inside bodies for the truth of disease. The violation of the body would be the revelation of its truth.

By transference, the idea of anatomizing became a potent medical metaphor during the next couple of centuries, as in Robert Burton’s Anatomy of Melancholy (1621) or John Donne’s poem ‘An Anatomy of the World’ (1611), and modern medicine adopted the anatomy lesson as its signature: medicine was represented as a probe into nature’s secrets, peeling away layer upon layer in the hunt for truth; nothing would resist its gaze. The knife also suggested other modes of mastery, not least sexual conquest, as when Donne likens the lover’s caress to a surgeon’s knife:

And such in searching wounds the surgeon is

As wee, when wee embrace, or touch, or kiss.

A new genre came into fashion: self-anatomy, introspection into one’s own soul, a kind of spiritual or psychological dissection. ‘I have cut up mine owne Anatomy,’ declared Donne, ‘dissected myselfe, and they are got to read upon me.’

Practical anatomy advanced on a broad front after the Fabrica. Accounts of the whole body continued to be published, for instance Charles Estienne’s (1504–64) De dissectione partium corporis humani (1545) [On the Dissection of the Human Body]. Realdo Colombo, an apothecary’s son who studied surgery at Padua, succeeding Vesalius there in 1544, corrected some of his errors in his De re anatomica [On Anatomy], published posthumously in 1559. He accused Vesalius of passing off descriptions of animal anatomy as human – precisely Vesalius’s charge against Galen. Colombo’s discovery of the pulmonary transit and elucidation of the heartbeat were momentous. Vivisection experiments showed that blood went from the right side of the heart through the lungs to the left side; that the pulmonary vein did not, as Galen had thought, contain air but blood; and that blood was mixed with air not in the left ventricle of the heart but in the lungs, where it took on the bright red hue of arterial blood. Describing the heartbeat, Colombo held, opposing former views, that the heart acted with greater force in systole (contraction) than in diastole (dilation); this too was crucial for Harvey.

Gabriele Falloppia (1523–63) was appointed in 1551 to perform the annual anatomies at Padua, and he produced more criticism of the Fabrica in his Observationes anatomicae (1561) [Anatomical Observations]. The tremendous kudos of the new anatomical teaching is illustrated by an incident in 1555, when the university authorities sought to revive the old style of anatomizing as ordained by the statutes. A junior lecturer was to read out Mondino’s Anatomia, and the senior professor, Vettor Trincavella (1490–1563), was to deliver theoretical lectures. Falloppia’s role as anatomist would thereby have been demeaned. In the event, Trincavella’s orations were broken up by rowdy students chanting vogliamo il Falloppio (‘we want Falloppia’), after which anatomy was entirely in his hands.

Falloppia’s Observationes may be regarded as a coda to the Fabrica, adding new observations and correcting errors in both Galenic and Visalia anatomy. Though not a systematic textbook, it covered a wide range of subjects, with emphasis on the skeleton, especially the skull, and the muscles. Particularly important were his descriptions of the structure of the inner ear, the carotid arteries, the head and neck muscles, and the orbital muscles of the eye. It also contains the famous description of the uterine tubes bearing his name. Falloppia meanwhile kept up a huge practice, claiming to have examined the genitals of 10,000 syphilitics.

Unlike Vesalius, later anatomists produced specialized studies of body parts, such as the treatises on the kidney, the ear and the venous system published by Bartolomeo Eustachio (c. 1500–74) in his Opusula anatomica (1564) [Anatomical Studies]. He scolded Vesalius for depicting a dog’s kidney instead of a human one, and produced figures of the ear ossicles and the tensor tympani in man and in dogs. The Eustachian tube from the throat to the middle ear was described, though priority really belonged to Giovanni Ingrassia (1510–80), who had discovered it in 1546.

Study of specific structures encouraged comparative anatomy, in which different animals were correlated in a self-consciously Aristotelian manner; Aristotle had been keen to compare animal anatomy for classification purposes and to discover essential structural/functional correlations. The greatest comparative anatomist was one of Falloppia’s pupils, Hieronymus Fabricius ab Aquapendente (Fabrizio or Fabrici: c. 1533–1619), who succeeded to his Padua chair in 1565. Fabricius’s aim was to produce a work to be called Totius animalis fabricae theatrum [The Theatre of the Entire Animal Structure], but only small sections emerged. As an anatomist he was less interested in Visalia structural architecture than a comparative approach which stressed three aspects of anatomy: the description, action, and use of body parts. Although Vesalius had surpassed the ancients in descriptive accuracy, he had written little on the action and use of the parts; this was what Fabricius aimed to remedy.

Fabricius’s most significant work was De venarum ostiolis (1603) [On the Valves of the Veins], for the venous valves were to be crucial for William Harvey’s demonstration of the blood circulation. It was not Fabricius who discovered them, but he was the first to discuss them at any length. The valves, he maintained, were designed to prevent the extremities from being flooded with blood and to ensure that the other body parts would get their fair share. This theory tallied with the Galenic view that blood was attracted from the liver, the blood-making organ, by each part of the body when it needed nourishment. The valves thus helped the central and upper parts to get blood by preventing its tendency to gather at the extremities.

Fabricius’s embryological treatises also influenced Harvey. De formatione ovi et pulli (1621) deals with the development of the egg and the generation of the chick, while De formatu foetu (1604) [On the Formation of the Foetus] describes how nature provides the means for foetal growth, nourishment and birth. His descriptions of foetal development lay within the Aristotelian theoretical framework of the female contributing the matter and the male the form.

A more idiosyncratic challenge to Galenic physiology had meanwhile come from the polymath Michael Servetus (1511–53). Sickened by the corruption of the Roman Church, Servetus went further than Luther along the road of heresy and developed anti-Trinitarian views, leading to condemnation by Catholics and Protestants alike. In Lyons he had met the medical humanist Symphorien Champier (c. 1471–1539), who advised him to study in Paris, where he worked with the cream of the faculty: Sylvius, Fernel and Guinther von Andernacht. But he soon fell under suspicion, and was condemned in 1538 by the Parlement of Paris for lecturing on astrology. In 1553 he anonymously published his major work, the 700-page Christianismi restitutio [The Restoration of Christianity], which was denounced by Calvin as heretical. Escaping the Inquisition, Servetus was nevertheless condemned for heresy on entering Calvin’s Geneva, and burnt at the stake.

It was in The Restoration of Christianity that Servetus announced the pulmonary transit of the blood, within the framework of an heretical account of how the Holy Spirit entered man. The Bible taught that the blood was the seat of the soul and that the soul was breathed into man by God: there had therefore to be a contact point between air and blood. This led Servetus to denounce Galen’s whole scheme. Blood did not go through the septum; he proposed instead a path from the right to the left heart through the lungs. Blood was mixed with air (that is, spirit) in the lungs, rather than in the left ventricle. Confirmation lay in the size of the pulmonary artery – its design was too large to transmit blood for the lungs alone. Servetus’s views had no influence on the development of anatomy, not least because almost all copies of his book were burnt with their author.

Renaissance dissections increased knowledge of the structure of man and other animals. But while precipitating an anti-Galen reaction, Vesalian anatomy followed his precepts: without Galen no Fabrica. Humanist anatomy was conservative in theory. No anatomist opposed the traditional Galenic tripartite division of physiologic function (venous, centered on the liver; arterial, centered on the heart; and sensory/motor, centered on the brain), even when anatomical structures and vascular connections crucial to the scheme were being discredited (for instance, the rete mirabile). For all their radical rhetoric, Vesalius’s generation shored up ancient medicine and philosophy even as they exposed its factual errors. All the same, Renaissance anatomists enormously elevated the standing of their subject. Its status had been low; it was not listed among the ancient major divisions of medicine, and was stigmatized by its surgical connexions; but the appointment of the physician Vesalius at Padua served notice that anatomy and surgery were to be incorporated into the wider humanist medical movement. The Fabrica’s preface argued for the unity of the different medical arts; physicians should not disdain to use their hands, an adage equally dear to contemporary experimental natural philosophers.

Anatomy became integrated into learned medicine – even in backward England, thanks to John Caius (1510–73). Caius was a Galenist physician and protégé of Thomas Linacre, who had been largely responsible for the founding of the College of Physicians in 1518, and for the medical lectureships at Oxford and Cambridge.

Educated at Gonville Hall in Cambridge, from 1539 Caius studied at Padua, teaching Greek and collecting manuscripts, particularly those of Galen, whom he idolized. On his return, he settled in the capital, being admitted Fellow of the College of Physicians in 1547. In his nine terms as president, Caius attempted to mould the college along continental lines, regulating medicine according to the best Galenic standards. He reorganized its statutes, and introduced formal anatomies into its lectures, also demonstrating anatomy before the Barber-Surgeons Company. In Cambridge he refounded his old hall in 1557 as Gonville and Caius College, serving as its master from 1559 and fostering a strong medical tradition, from which William Harvey (1578–1657) was to benefit. Through enthusiasts like Caius and his equivalent in Leiden, Pieter Pauw (1564–1617), anatomy became incorporated throughout Europe into the humanist revival.

Anatomists presented their subject as the cutting edge; the way to certain knowledge was through the senses, especially by ‘autopsia’, seeing for oneself. Though the Paduan Aristotelian philosopher Cesare Cremonini (1552–1631) was still insisting in 1627 that anatomy could never be the foundation of medicine (only causes, the domain of philosophy, and not observation could lead to certainty), the sheer success of anatomy swept this dogma aside. Dissections became public events: at Bologna they were staged during the annual carnival, the macabre fascination of the memento mori, juxtaposing life and death, contributing to the appeal. Rembrandt’s ‘The Anatomy Lesson of Dr Nicolaes Tulp’ (1632), shows that anatomy had become one of the spectacles and symbols of the age. Not only the method of medicine, anatomy became accepted as a window onto the human condition.