Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

Kitabı oku: «The Assistant»

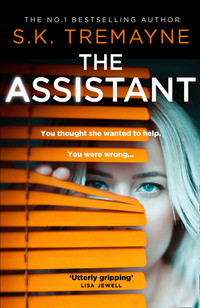

THE ASSISTANT

S. K. Tremayne

Copyright

HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2019

Copyright © S. K. Tremayne 2019

Cover design by Claire Ward © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2010

Cover photographs © plainpicture/Philippe Lesprit (front cover); David Paire/Arcangel Images (back cover).

S. K. Tremayne asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books

Source ISBN: 9780008309510

Ebook Edition © December 2019 ISBN: 9780008309534

Version: 2020-09-10

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Author’s Note

Chapter 1. Jo

Chapter 2. Jo

Chapter 3. Jo

Chapter 4. Jo

Chapter 5. Janet

Chapter 6. Jo

Chapter 7. Jo

Chapter 8. Jo

Chapter 9. Jo

Chapter 10. Jo

Chapter 11. Jo

Chapter 12. Jo

Chapter 13. Jo

Chapter 14. Jo

Chapter 15. Jo

Chapter 16. Polly

Chapter 17. Jo

Chapter 18. Jo

Chapter 19. Jo

Chapter 20. Jo

Chapter 21. Dr Hussain

Chapter 22. Jo

Chapter 23. Jo

Chapter 24. Jo

Chapter 25. Jo

Chapter 26. Jo

Chapter 27. Jo

Chapter 28. Simon

Chapter 29. Simon

Chapter 30. Jo

Chapter 31. Jo

Chapter 32. Jo

Chapter 33. Jo

Chapter 34. Jo

Chapter 35. Jo

Chapter 36. Jo

Chapter 37. Jo

Chapter 38. Tabitha

Chapter 39. Jo

Chapter 40. Jo

Chapter 41. Jo

Chapter 42. Jo

Chapter 43. Jo

Chapter 44. Jo

Chapter 45. Jo

Chapter 46. Tabitha

Chapter 47. Jo

Chapter 48. Jo

Chapter 49. Jo

Chapter 50. Jo

Chapter 51. Jo

Chapter 52. Jo

Chapter 53. Jo

Chapter 54. Simon

Chapter 55. Jo

Chapter 56. Jo

Keep Reading …

About the Author

Also by S. K. Tremayne

About the Publisher

Author’s Note

There are numerous quotations from the works of Sylvia Plath throughout the book. These lines are taken from her poems ‘Death & Co’, ‘The Bee Meeting’, ‘Disquieting Muses’, ‘Electra on Azalea Plath’, ‘Facelift’, ‘Mirror’, ‘Elm’ and ‘Childless Women’.

I must thank Faber & Faber for permission to quote, more widely, from two poems in particular: ‘Munich Mannequins’, and ‘Daddy’, both in the Collected Poems of Sylvia Plath.

As usual I owe a huge debt of gratitude to my agent Eugenie Furniss, and editors, Jane Johnson and Sarah Hodgson, for their characteristic wisdom, and insight.

Finally, I would like to thank my beloved wife, Star, for the many times she unknotted problems, and offered ideas, along the way.

1

Jo

Are you a woman, man, other?

Well, that’s easy enough. Despite that curious wish for a twirly moustache, age ten, and a twelve-year-old’s desire to be an astronaut, which came with the vague yet outraged sense that only boys could be proper astronauts, I am quite sure on this one.

As the daylight in the room shades to grey, I lean towards my shining laptop screen and click,

woman

Are you straight, gay, bisexual, other?

A pause. A long pause. I’ve no doubts about my sexuality, I’m just bemused by what other might mean in this context. What is that fourth possibility of sexuality? A desire for ghosts? Ponies? Furniture? My dear beloved mum can get oddly excited when reading magazines about interior decoration. But I somehow don’t think her demographic is the target of this website.

On the other hand, sitting here at my laptop in the fading winter light, I’d quite like a fourth choice, or a fifth choice, or, dammit, seventy-eight choices. Because if you were in a critical mood you could say my choices so far in life have not turned out entirely optimal: divorced, childless, and nearly homeless at thirty-three. OK, yes, I might be living in a sleek flat in the nicer end of Camden, North London – where it merges into the real, five-storey Georgian opulence of Primrose Hill – however, I know I’m only here because my richer friend, Tabitha, took pity on her newly divorced and virtually bankrupt old university mate. Hey, why don’t you have the spare room, I really don’t use it much …

I think it was the casually generous way she made this offer, the blasé effortlessness of it all, which confounded me. At once it made me feel impossibly grateful, and even more fond of Tabitha – funny, kind, generous, and the best of best friends – yet it also made me feel guilty and a tiny tiny tiny bit jealous.

Turning from the laptop, I look out of the darkening window. And see my own face reflected.

OK, I was properly jealous, if only for a minute or two. What barely mattered to Tabs – Here, have a spare room, somewhere really nice to live – was so crucial and difficult for me, and she was barely aware of the emotional difference.

This is because Tabitha Ashbury already owns, Tabitha Ashbury will also inherit. I love her but she’s never understood what it’s like not to have all that: in London.

By contrast with Tabitha, I’m not just Generation Rent, I am Generation Can’t Afford to Rent Anywhere Without a Major Knife Crime Epidemic. And it doesn’t look like this is going to change any time soon, because I’m a freelance journalist. I have become a freelance journalist when the phrase freelance has become a kind of fantastical joke in itself: hey, look, I know that these days you basically have to write for free, but where’s my lance? Don’t we go jousting as well?

This career, however, was – for all its challenges – definitely one of my smarter choices. I love my job. The work is varied and compelling, and every so often I get to think I have changed the world slightly for the better, revealing some scandal, telling a decent story, making someone I’ll never know chuckle for two seconds, over a sentence that may have taken me six hours to get right. But that scintilla of human gladness wouldn’t have existed if I hadn’t made the effort. Or so I hope.

Reverting to my computer I refocus on OKCupid. I may have a home (however fortunate), I might have a job (however sketchy the salary), I have, however, no other half. And I am beginning to feel the absence. And perhaps the magic of internet dating will guide me, like a digital fairy godmother, with a wand of sparkling algorithms, to a new man.

I answer the question:

straight

With this, my laptop screen instantly flashes, and grows even more vivid: whisking me into a world of warm, cascading images of What Could Be: luridly happy pictures of emotional and erotic contentment, where beautiful couples sit laughing, very close together.

Here’s a smiley young Chinese woman sipping red wine and draping a slender arm over a handsome Caucasian man with enough stubble to be masculine without being prison-y; here are the white and black gay boys holding hands as they put red paint on each other’s faces in a carnival mood; here is the exceptionally well-preserved older couple who found love despite it all – and now seem to inexplicably spend all their time grinning on rollercoasters. And all these happy ThankyouCupid! people are promising me something so much better than the view through the big high black sash windows of this million-quid flat: looking out onto the chilly, frigid, 3 p.m. twilight of wintry London. A world where it is getting so cold and dark the angry red brake lights of the cars, jammed, stalled, impatient, fuming, on busy Delancey Street, glow like red devil eyes in Victorian smoke.

I turn to one of Tabitha’s Home Assistants, perched on the bespoke oak shelving at the side of the elegant living room, with its elegantly lofty ceilings. Everything in Tabitha’s flat is so elegant and tasteful I sometimes tell her I am going to buy, say, a plastic gnome-themed clock from the discount supermarket on Parkway to ‘brighten things up’, then I wait, straight-faced, for her to get the joke, and then we both laugh. I love living with Tabitha. That deeply shared sense of humour: possibly you only get that with a certain kind of old friend?

Or an ideal kind of lover.

‘Electra, what will the weather be in London this evening?’

The top of the black Home Assistant glows in response, an electric green-to-sapphire diadem, and in that faintly pompous, hint-of-older-sister voice, the voice of a sibling who went to a rather superior school, she answers:

‘Tonight’s forecast in Camden Town has a low of one degree Celsius. There’s a sixty per cent chance of rain after midnight.’

‘Electra, thank you.’

‘That’s what I’m here for!’

Simon and I had an earlier, cheaper version of these smart-heating, smart-lighting Home Assistants, but Tabitha has the full and latest range: Electra X, HomeHelp, Minerva Plus – everything. They’re scattered throughout the flat – six or seven of them – answering questions, telling contrived bad jokes, advising on the rate of the pound against the dollar, reciting news of earthquakes in Chile. They also precisely calibrate the temperature in each room, the ambient lighting in the bedrooms, and quite probably the amount of champagne (lots of it vintage; none of it mine) in the stern and steely magnificence of the eight-foot-high fridge, where you could store a couple of corpses standing upright and still have room for your cartons of organic hazelnut milk.

The irony is that Tabitha barely uses the marvellous tech of her smart-home, or drinks her spirulina smoothies and hazelnut milk, because she is barely here. She is either abroad, in her job as a producer for a nature TV channel, or she’s at her fiancé Arlo’s delicious period house in Highgate, which is even plusher than here. He probably has machines so advanced they can invite precisely the right friends over for spontaneously successful threesomes.

I miss sex. I also miss Tabitha’s company; when I moved in, I hoped I’d see more of her. I believe, sometimes, I simply miss company. Which is perhaps one reason why I like, to my surprise, the Digital Butlers. The Assistants. Sometimes I josh and banter with the machines purely for the sake of hearing a voice other than my own: Tell me the weather in Ecuador, Why are we here, Is it OK to watch soft porn while eating Waitrose dips?

I think, in a way, these gadgets are like less annoying and demanding pets that do charming and useful things, dogs that don’t need walking yet still fetch tennis balls, or slippers – or ‘the papers’, as my mother still, charmingly, refers to her precious daily delivery of printed news. I sometimes fear that she is possibly one of the last people on earth to say, ‘Have you read the papers?’ and when her generation goes my career will finally fall off that cliff.

Anyway.

‘Electra, shall I get the fuck on with writing this profile?’

‘I’d rather not answer that.’

Hah. There she goes again, using the voice of the prim, sensible, better-educated older sister that I never had – who disapproves of swearing. My only real sibling is older, and a brother. He lives in LA, works in the movie industry, and he’s married to a chatty lawyer and has a lovely little son, Caleb, whom I adore. And, as far as I can tell, he spends his time going to meetings and pool-parties where they talk about movies being ‘greenlit’, or suffering in ‘development hell’ – rather than actually making movies.

I’d quite like him to actually make movies, because I’d quite like him to make a movie or TV series written by me. One day. Oh, one day. I see it as my only way out of my cul-de-sac career, however enjoyable. These days, the money is in movies and TV; it’s certainly not in journalism. I recently estimated I have about £600 in savings; literally £600, max, stored in some precious ISA. They say you are only two months’ missed wages from living on the street; that means I could be out there, in the cold, in about ten days, if the bank ever got tired of my overdraft.

As a result I am busily reading every how-to guide on scriptwriting that I can, learning about beats, hooks, cliffhangers, and three-act structures, and reading experts like Syd Field and Robert McKee and so far every script I’ve written has turned out rubbish, every mystery and drama lacks drama and mystery, but I will keep trying. What choice do I have?

I turn, in a playful mood, to the oak shelving.

‘Electra, give me an idea for a brilliant movie.’

‘Sorry, I’m not sure.’

‘Electra, you’re totally bloody useless.’

Silence.

‘Electra, I’m sorry I swore. It was only a joke.’

She does not respond. She doesn’t even show that braceleting glow of greeny-blue. That’s odd. Is she malfunctioning? Or have I truly offended her this time?

I don’t think so. It’s quite hard to emotionally offend a cylinder of plastic and silicon chips. In which case I should stop faffing, and get on with this online dating profile.

Back to the drawing board: the drawing of myself. Online.

First name?

Jo

It’s actually Josephine, but I shortened it to Jo when I was a teen because that seemed cooler. And I stand by my teen decision. But will it make men think I am masculine? If they do they are idiots, and not the men I want.

Jo

Jo Ferguson

Age?

Well? Shall I? Nope.

I know some women of my age – and men – who have begun to knock off a couple of years, on Tinder and Grindr and PantsonFire, but I feel no need. I am thirty-three, nearly thirty-four. And happy with it. Sure, I am beyond the first rose-flush of youth, but hardly ready for composting. I can still catch the sense of a man turning to glance as I disappear the other way.

33

Location?

London

Postcode?

This is tricky. To anyone that knows the intricate class signals, the invisible social pheromones subtly emitted by London postcodes, my present postcode NW1, can make me sound, at my age, like someone rich, or rich and bohemian. Someone who hangs out at the Engineer pub with actors and ad moguls. Either that or a single mum turned drug dealer.

Yet I’m not NW1: I’m neither druggie nor bohemian; I’m still much more N12, North Finchley, where until recently I lived with my ex-husband Simon in a mediocre, damp, and definitely rented two-bed flat with OK bus connections to nice Muswell Hill. And even deeper inside me is the real me, the girl who grew up way way down in SE25, Thornton Heath, a slice of forsaken, tatty, you’re-never-more-than-two-minutes-from-a-kebab-shop outer London, a burb so obscure it is unknown even to other outer Londoners, who make wearily predictable jokes like Do I need a visa to get there. So yes, I am intrinsically either a 25 or a 12 – but at this moment, by sheer dumb luck, I am a 1.

Why I am worrying?

NW1

‘Electra, what’s the time?’

‘The time is five thirty p.m.’

Five thirty?

I have spent an hour, or two – and so far I’ve given my name, gender, age, and address. Sighing at myself, and clicking through, the OKCupid screen changes to a sensitive aquamarine, perhaps because the questions are growing increasingly piquant.

Are you looking for:

1 Hook-up?

2 New friends?

3 Short-term dating?

4 Long-term dating?

At the bottom there’s an option for Are you open to non-monogamy?

Ouch. Part of me would like to answer the last question: I certainly was, as that is the truth. But it is surely too truthful: it was me that started it, it was me that lit the long sad fuse that led to our divorce. I started it with funny sexy Liam, the barman and would-be actor. Liam’s initial approach was entirely innocent, a throw-away compliment about my journalism, on Twitter, from a guy I’d never met. Then we became Facebook friends, and Instagram pals, and WhatsAppers, and within a few days of online chat I was sending this smart, witty, diverting guy endless sexts and nude selfies, because I was bored, because my marriage was stale, because I was foolish, because it was fun even as I knew it was wrong – so I can hardly blame Simon, my husband, for having an affair with Polly the pleasant nurse after he discovered my three months of virtual infidelity.

I’ve heard since that Polly doesn’t like me so much; I am the ex that looms a little too large in Simon’s life. But what can I do? She’s right to dislike me. Or it is, at least, totally understandable.

Sadness descends. Alongside memory, and guilt. Staring at the OKCupid site, I feel, quite suddenly, as if it is asking me too many questions. What’s it going to ask next? How do you feel about your father?

Leaning forward, I put the laptop to sleep. Like stroking a cat that instantly snoozes. I’ll finish this profile later. I need air, darkness, freedom.

‘Electra, I’m going for a walk up Primrose Hill.’

The blue ring dances in response. It whirls around fast, then even faster, as if something is inside it. Something maddened, and angry. Definitely alive. Is it meant to do this? The sensation is unnerving – but I’m not quite used to the tech yet. I need to read the online instructions. It is probably designed to react this way.

The blue light spins to a stop. And blinks out to black.

Picking up my coat, I go into the kitchen and make a mug of hot coffee, then, carrying this, I head for the door. I need the anonymity of the endless streets. The great and indifferent city.

I love the size of London for this reason: its vastness. No one cares who you are. No one knows your secrets.

2

Jo

The wind is satisfyingly bitter in its cold; carrying a vivid rumour of snow. Wrapping my multicoloured don’t-run-me-over scarf around my face, I cross the junction of Parkway, the social divide that separates the posher end of Camden from the ultra-poshness of Primrose Hill, which hides like a snooty and castellated village behind its canals and railways and the expanse of Regent’s Park.

I am still clutching that mug of hot coffee. It’s for our local homeless guy, who usually sits on a wall on the other side of Delancey Street, between the pub and the railway cuttings. He’s a tall black guy in his fifties with a sad, kind face, and wild hair. When I first moved in, Tabitha told me he’s from the homeless shelter on Arlington Road, and that he likes to shout about cars. I like cars. Do you like cars? Mercedes, that’s a car. Cars!

For that reason, she calls him Cars, he’s the Cars guy. Apart from that, she simply ignores him. In the last few weeks, however, I’ve got to know him. His real name is Paul, though in my head I can’t help calling him Cars, like Tabitha. Sometimes, on cold nights like tonight, I go outside with a mug of hot tea or soup to keep him warm, and then he says I am pretty and should have a husband, and then he turns and starts shouting CARS CARS CARS! and I smile at him, and I say, See you tomorrow, and I walk back inside.

This evening, however, is too cold even for Paul: he has stopped yelling Bentleys! and he is huddled in a corner of the railway wall, barely speaking. But when he sees me, he emerges, smiling his blank sad smile.

‘Hey! Jo! Did you guess I was cold how did you do that?’

‘Coz it’s totally bloody freezing. Shouldn’t you go back to the hostel? You could die out here, Paul.’

‘I’m used to it.’ He shrugs, eagerly taking the coffee. ‘And I like watching the cars!’

I shake my head and we smile at each other and he tells me he will give me back the coffee mug tomorrow. As ever. He often forgets, so I have to buy new ones. I don’t mind.

Waving him goodbye, I walk on.

A taxi shoots past, orange light bright, glowing, desperate for business. I wonder if Uber will kill off London cabs before the internet kills off paid journalism. We’re both on our last legs: positively racing towards annihilation, hurtling into the dark London drizzle. But I don’t want to die yet. Not when I’m about to write that killer script. Probably.

Waiting for the traffic lights to change, I jog, impatiently, to keep warm. I know where I’m going: my exact route. I walk it almost every evening. Regent’s Park Road, then up the hill, then the main street of Primrose Hill village, then curving round Gloucester Avenue and home. It takes me roughly forty-five minutes. I wonder if people have learned to recognize me by the sheer regularity of my patrol: Oh, here comes that woman who always walks this way. What is she looking for?

As I cross the road, I have an idea: I’m going to ring Fitz. Who I met through Tabitha, years ago. Yes. Slender, darkly greying, smartly charming, cynical-yet-theatrical Fitz. We could go for a drink somewhere. Get an Uber to Soho gay bars, where he is usually found; I like the way everyone in these bars will abruptly stop drinking and sing lustily to the chorus of Andy Williams’ ‘Can’t Take My Eyes Off You’.

I Love You Baaaaby …

Passing the grand pastel houses by St Mark’s church, I pluck my phone from a warm pocket and dial with cold fingers.

Voicemail.

‘Hi, this is Fitz, you’re out of luck, darling. I’ll tell you everything tomorrow.’

That’s his usual voicemail message. Deliberately camp. I laugh, quietly, into the dewy cold wool of my scarf, then scroll further down my contacts. Who else can I call? Who could I drink with? Tabitha is in Brazil. Carl is out of town working. Everyone else … Where is everyone else?

They’ve gone elsewhere, that’s where everyone else is. The truth of this bites deeper every time I open my phone contacts. My drinking pals, my peer group, my beer buddies, the sisterhood, the tribe of uni friends: they’ve dispersed. But it’s only since I divorced Simon that I’ve realized just how many of my friends have dispersed: that is to say: got married, stayed married, had kids, and moved out of London to places with gardens. It is, of course, what you do in your thirties, unless you’re rich and propertied like Tabitha. Living in London in your twenties is hard enough – exacting but exciting, like glacier skiing – having a married life with kids in London in your thirties is essentially impossible, like ascending a Himalaya without oxygen.

I am one of the last left. The last soldier on the field.

Crossing Albert Terrace, I start the walk up Primrose Hill as my fingers pause on J for Jenny. She’s probably about my only childhood friend left, Simon apart. Jenny used to be around my house all the time, for playdates and sleepovers, then her parents divorced and she moved away, and I pretty much lost touch, though Simon kept a connection with her because they ended up working in the same industry.

Jenny is employed, in King’s Cross, by one of the biggest tech companies. That’s how Jenny and I reconnected: when I was writing my big breakthrough article, three or four years ago, on the impact of Silicon Valley on our lives.

I knew this story could make my name, impress my editors, drag me up the ladder a few rungs, so I shamelessly exploited my contacts (my husband), I seriously pissed off some particular sources by naming them (sorry, Arlo), but I met some fascinating people, a couple of whom became friends. And I rediscovered an old friend.

She picks up immediately. I love you, Jenny. That precious link to the past, to the time before everything went wrong. The times when Daddy would chase us in the house, in Thornton Heath, playing Hide and Seek, making us giddy with happy terror: shouting out, I can HEAAARRR you. And Jenny and I would huddle together, giggling, under the bed or in the dark of the wardrobe.

Ah, my lost childhood.

‘Hey, Jo. What’s up?’

‘I’m bored.’ I say, with some vehemence, ‘Horribly bloody booorrrrreeeeed. I’m trying to build a profile on OKCupid but it’s depressing and tragic, and I thought you might like to share a barrel of prosecco. Two barrels. A yardarm. What is a yardarm, anyway?’

She chuckles.

‘Ah, love to, but sorry.’

I can hear the characteristic chank of her Zippo lighter, then inhalation. Traffic murmurs in the background. Is she outside?

‘Where are you?’

‘King’s Cross, having a ciggie break. But I better go back in – I’m at the Death Star.’

‘Oh?’

‘Yep,’ she says, exhaling smoke. ‘Working till, like, midnight or something.’ She draws on her cigarette, goes on, ‘Jesus, it’s cold out here.’

Jenny works absurd hours at HQ. She probably makes a lot of money coding or whatever, but doesn’t talk about it. She mostly talks about sex. Jenny, apparently, is my Official Slut Friend. The insult is not mine, I would never have said it. But she said it herself when we renewed our friendship over mussels and chips in some bar near her work. Everyone has to have a slutty friend, she said, to make them feel better; have you got a slut friend, someone even more promiscuous than you? She made me laugh, at that table, she makes me laugh now, she always gives good gossip, and there’s a sadness in her hedonism which makes her funnier, and warmer.

I press the phone closer to my freezing ear, as Jenny asks:

‘How’s the profile-building going?’

‘Ah. Not great …’

I pause, to take a breath. I’m nearly at the top of Primrose Hill: the last, steep incline which always makes me gasp cold air. I should definitely start going to the gym. Jenny tries again,

‘Not great? What does that mean?’

‘It means, I’ve been at it several hours, and I’ve established that I’m straight, thirty-three, a woman, and I’m looking for long-term, short-term, casual hook-ups, or maybe a snog in a pub toilet. Do you think I might be coming across as desperate?’

‘Hah. No. Stay strong! There has to be a good man out there? I’ve seen them!’

‘No chance of a drink, then?’

‘Not tonight, Josephine. Call me tomorrow, mabes. OK, I’ve gotta get this TEDIOUS code written before I turn into a bat. Good luck!’

The phone clicks. I am at the top of the Hill. I don’t know whether it is the jewelled skyline of icy London – always impressive from this vantage point, stretching from the silvery towers of Canary Wharf to the holy scarlet arc of the London Eye – it could be the mere fact of hearing Jenny’s friendly voice – but I feel distinctly cheered. Invigorated. The sadness is dispelled.

Jenny is right. I must woman up. I can do this. It’s only a bloody dating profile. And I need a bloody date.

It’s all downhill from here, I can’t be bothered to do the full circuit, so I’m simply going to retrace my steps, back down Regent’s Park Road, as the snow begins to fall, heavier by the second. My pace quickens as I hurry past the big, white, thoroughly empty mansions.

Sometimes it feels like a ghost town, this rich little corner of London. Streetlamps shine on cold pastel walls, leafless trees grasp at the frigid orange sky. Glossy new apartment blocks sit empty: from one month to the next. Windows forever black and cold like Aztec mirrors, obsidian squares reflecting nothing. Where is everyone?

Nowhere. There is no one here. It’s only me. And the snow.

Ten minutes later I am sat at the laptop, gazing at OKCupid again, trying to make my personality sound simultaneously attractive, different, sexy, not too sexy, witty, not self-consciously witty, diverse, truthful, self-confident, but not brash. I mustn’t give up, but the questions? There are so many.

OK, I reckon I need a gin and tonic. Indeed, I need two punchy G&Ts: that should be about right, make me brave and honest and a little bit funny, without being idiotic. I was once told by an expert (someone who went on live TV daily) that the perfect amount of alcohol you need to cope (with daily live TV) is half a bottle of champagne. Similarly, I reckon two G&Ts is the perfect amount of alcohol to cope with any difficulty in life.

Returned from the kitchen, second G&T in hand, I command myself, and type.

Ethnicity?

English

Height?

Five foot two

Education level?

Useless degree