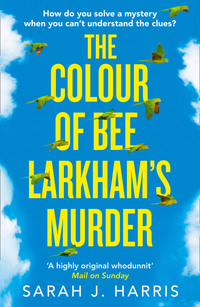

Kitabı oku: «The Colour of Bee Larkham’s Murder», sayfa 2

‘Jasper—’ Dad starts.

‘That’s OK.’ Rusty Chrome Orange holds up his hand like he’s directing traffic.

I hope he’s better at that than interviewing me about serious crimes.

‘Your dad’s already explained you suspect someone on your street has killed a few parakeets that nest in Miss Larkham’s front garden.’

‘I know twelve parakeets are dead. Thirteen, if you count the baby parakeet, which died on 24 March, but that was an accident. The other deaths were definitely deliberate.’

Rusty Chrome Orange’s head bounces up and down. ‘I understand you’ve found recent events hard to come to terms with.’

‘Yes,’ I confirm. ‘Murder upsets me.’

‘Stop it, Jasper!’ Dad warns.

Rusty Chrome Orange stops cars again with his hand. ‘It’s OK, Mr Wishart. I can handle this.’

He leans towards me and I almost fall off the cushions to escape from him.

‘Don’t worry, Jasper. We can certainly discuss your concerns about the death of the parakeets. But first, I’d like to talk about your friends: Bee Larkham and Lucas Drury.’

Where did the Metropolitan Police find this man? Is he the last human survivor of a zombie apocalypse? Honestly, I thought this was what we were talking about before he changed the subject abruptly and brought up the massacre of my parakeets.

I should give him another chance, I suppose, even though he’s stupid enough to think Lucas and me are friends. We’ve never been friends. We were Bee Larkham’s friends. Her willing accomplices.

I try again to make him understand. ‘Ice blue crystals with glittery edges and jagged, silver icicles.’ I emphasize the icicles because that’s important. It’s the one thing about Friday night that sticks in my mind. The rest is too blurry; too many blanks and curly question marks, but the icicles’ jagged points remind me of the knife.

‘You’ve told me that twice already, but I’m afraid artists’ colours don’t mean a lot to me,’ Rusty Chrome Orange says. ‘Look, I’m sorry if I’ve confused you. Let’s be clear, none of the boys we’re speaking to are in any trouble or danger. We’re trying to establish a few background facts before we track down Miss Larkham and speak to her ourselves.’

I’m attempting to tell him he’ll never be able to speak to Bee Larkham, but he’s not interested. His voice grates like nails down a blackboard.

‘I want to go home.’

‘Please, Jasper. Concentrate. It’s not for much longer.’ Dad’s muddy ochre has a yellowish pleading tone.

‘I can’t do this. I’m too young. I can’t do this. I’m too young.’

I speak loudly, but Dad doesn’t hear.

‘Jasper’s hardly an ideal witness in your investigation,’ he says. ‘There must be other boys at his school who can assist you? Boys who don’t have as many special needs?’

I need to go home. That’s my special need. My tummy’s hurting. No one’s listening. They never do. It’s like I don’t exist. Maybe I’ve melted away beneath my fingertips into nothing.

‘I understand your concerns, Mr Wishart. I’ll raise them at our case meeting this week, but we need to look closer at Jasper’s relationship with Miss Larkham and Lucas Drury. We believe he may have information that could assist our inquiries. He may have made notes of important times and dates in their alleged relationship.’

‘I doubt it.’

A fluttering of pale lemon.

One of my notebooks protests against Dad’s probing fingers.

‘Look at this entry. The people going in and out of Bee’s house have only basic details: Black Blazer enters, Pale Blue Coat leaves, etc. Jasper has no sense of what they look like, even if they’re teenagers or adults. I doubt he’d be able to identify Lucas or any other boy.’

Dad flicks through my notepad.

‘Most of Jasper’s entries don’t even record people. They’re his sightings of the parakeets nesting in Bee’s tree and other birds. He’s a keen ornithologist.’

Rusty Chrome Orange’s hand dips into a box and pulls out a steel blue notebook with a white rabbit on the front.

‘That’s not right,’ I say, surprised. ‘The rabbit doesn’t belong there.’

‘OK, sorry,’ Rusty Chrome Orange says.

The white rabbit notebook returns to its hiding place in the box.

‘Look at this notebook,’ Dad says, holding up another. ‘It’s all about his colours. How’s that interesting to you? To anyone?’

I want to scream and kick and flap.

Dad doesn’t see my difference in a good, winning-the-X- Factor-kind-of-way. He doesn’t look for the colours we might have in common, only those that set us apart.

I need to hold on. I have to focus on the colour I love most in the world: cobalt blue.

That’s all I’ve got left of Mum – the colour of her voice – but after Bee Larkham moved into our street the shade became diluted. It happened gradually and I never noticed until it was too late.

‘Take me home!’ I say. ‘Now! Now! Now!’

The colour and ragged shape of my voice shocks me. It’s usually cool blue, a lighter shade than Mum’s cobalt blue. Today it looks strange. Is it actually a darker shade than Mum’s? More greyish? I can’t remember. I need to remember her. I want to paint her voice.

‘I have to leave!’

It’s too late. Her colour’s slipping from my grasp, sand through my fingertips. I plaster my hands to my eyes. I want to keep the cobalt blue, vivid, reassuring, behind my eyelids.

Rub, rub, rub.

I want her cardigan. I forgot to bring one of the buttons to rub because I was concentrating on making sure my boxes were correctly ordered.

I glance across the room and the back of my neck prickles. Rusty Chrome Orange told me the mirror was ornamental, like the ship picture on the far wall. He insisted there’s no one behind it, but I can’t trust his colour.

Someone is standing behind the mirror, scrutinizing my face, my mannerisms and laughing at my mix-ups. There are three strangers sitting on crimson sofas on this side of the mirror.

I don’t recognize any of them.

The smallest, the one with dark blond hair who is rocking backwards and forwards, opens his mouth and screams.

Pale blue with violet-tinged vertical lines.

He vomits on the sofa.

Dad’s silent. He doesn’t flick on Radio 2 or tap his fingers on the steering wheel. I guess it’s not surprising, considering the whole embarrassing vomit thing. He’s still angry with me even though Rusty Chrome Orange said not to worry. Lots of kids throw up in that room; the police service employs someone to scrape up their sick. Dad says that’s the deadbeat career I’ll end up with if I don’t work harder to control myself.

The sofa had definitely seen a lot of sick action. What does Rusty Chrome Orange expect when he hangs a trippy mirror on the wall? One minute you think you’re alone and the next you’re surrounded by strangers.

He showed me behind the mirror after I’d calmed down; it was a normal wall.

No hidden window into another room.

No hidden recording devices.

I attempt to block out the dark colours and harsh shapes of the lorries and cars rumbling past. Dad hasn’t said a word since he turned on the engine, marmalade orange with pithy yellow spikes. Maybe he’s not angry with me. Maybe he’s thinking about Bee Larkham.

He knows we both need time to think about what’s happened – me without distractions of unnecessary colours and shapes, him without me banging on about my colours and shapes.

I should try to make him feel better, considering everything he’s done for me. He hasn’t forced me to come out of my den over the last three days except to visit the police station. He rang my school yesterday and said I had a bad tummy ache. At least that wasn’t a lie.

‘Don’t worry, Dad,’ I say finally. ‘I think we did it.’

‘We did what?’ he asks, without glancing back.

‘We got away with murder. Richard Chamberlain – like the actor – knows nothing.’

Dad spits out a yellowish cat-puke word.

I hate swearing. He knows I hate swearing.

He’s getting back at me for throwing up over Rusty Chrome Orange’s sofa.

‘I’m sorry, Jasper. I shouldn’t have used that word. Have you understood anything I’ve told you? Is that what you think’s happened?’

I screw my eyes tightly shut and curl into a ball beneath the seat belt.

Yes, I do. Think. That’s What Happened Back There.

Despite his repeated warnings to keep quiet, I tried to confess. Honestly I did, because I’m very, very sorry about what happened in the kitchen at 20 Vincent Gardens. I deserve to be punished.

Rusty Chrome Orange wouldn’t listen. I doubt he’s going to start looking for Bee Larkham’s body.

Which gives me time.

Time to protect the surviving parakeets. I need longer, around four days until the young begin to abandon the nests in Bee Larkham’s oak tree and eaves and fly far, far away from the dangers lurking on our street.

But I can’t leave.

I can’t ignore the colours any more.

I have to face the truth. I have to remember what happened the night I murdered Bee Larkham.

TUESDAY (BOTTLE GREEN)

Evening

LYING IN BED THAT night, I trace my index finger over the ring-necked parakeet photographs in my Encyclopaedia of Birds. The adult male parakeet is easily identifiable because of the pink-and-black ring around its neck. Females also have these rings, but they’re similar shades of green to their bodies and harder to pick out.

Twelve deaths in total.

Bee Larkham didn’t tell me how many males versus females were slaughtered before she died. I must start a new census before it’s too late. Before the nests are abandoned.

After we got home from the police station, Dad didn’t ask if I felt up to afternoon lessons. While he made cheese toasties and looked for painkillers for my tummy, I grabbed my half-empty bag of seed. I managed to get to the hallway before he stopped me.

Don’t go over to Bee Larkham’s house to feed the parakeets.

Promise?

Don’t put pieces of apple on the ground in our front garden for the birds. It’ll attract rats.

Promise?

No more 999 calls.

Promise?

It’s a pinkish grey word with curly edges, which always gives me a strange, achy feeling inside my tummy – not on the outside where it currently burns like dry ice and looks like a half-open mouth.

I agreed, but had my fingers crossed behind my back, which means it didn’t count. Someone has to feed the parakeets because Bee Larkham can’t do it any more.

Dad doesn’t realize it yet, but Bee Larkham’s house is already attempting to grab attention. The six bird feeders in her front garden have been empty since Friday night. She hasn’t strung up any monkey nuts or put out plates of sliced apple and suet. Bee Larkham didn’t turn on her music to full blast as usual. The parakeets weren’t serenaded and the neighbours didn’t complain about the noise. Earlier today, she didn’t open her front door to the piano and guitar pupils who are allocated forty-five-minute slots after school from 4 p.m. onwards. The house has remained dark and silent since Friday – the Indigo Blue day Bee Larkham died.

I know these Important Facts because I barricaded myself in my bedroom after Dad stopped me leaving the house to feed the parakeets. At first, I concentrated on painting Mum’s voice, but the shades were off. The colours were uncooperative and churlish. That’s the way Dad describes me.

Difficult.

He said he was working from home for the rest of the day, but I could see the colour of the television downstairs while I painted. Half an hour later, when Mum’s true cobalt blue refused to reveal itself and the black-and-silver stripes of the TV became too distracting, I had abandoned my tubes of blue paints and stood at the window with my binoculars.

As usual, I had kept a record of all the relevant activity and used a fresh cornflower blue notebook. I started it especially because it seemed like the right thing to do – to keep my ‘after’ notes separate and uncontaminated from the ‘before’ notes.

3.35 p.m. – Male parakeet flies into branches, berries in beak.

4.02 p.m. – Bee’s piano lesson. Kingfisher Blue Coat Boy two minutes late. Runs up path. Looks at empty bird feeders. Bangs cardboard box colour on door. Door doesn’t open. Kingfisher Blue Coat Boy walks down street.

4.11 p.m. – Five young parakeets together on branch.

4.45 p.m. – Bee’s guitar lesson. Sea Green Coat Boy taps lighter, dusty brown. Door doesn’t open. Sea Green Coat Boy gets back into black car.

Bee Larkham also had an unexpected appointment that wasn’t on her usual teaching schedule.

5.41 p.m. – Dark Blue Baseball Cap Man.

Bang, bang, bang.

‘Open the door, Bee! We need to talk!’ Clouds of dirty brown with charcoal edges.

I was tempted to lean out of my window and shout: Go away and take your clouds with you!

Of course, I couldn’t. I was too afraid of the Dark Blue Baseball Cap Man. I wasn’t sure if I’d seen him before, but knew I didn’t like his colours. Or his baseball cap.

I had scanned the tree with my binoculars. The parakeets remained hidden in the highest branches; even the youngest didn’t draw attention by squawking noisily. Clever birds.

5.43 p.m. – Dark Blue Baseball Cap Man walks backwards down path, staring up at Bee’s bedroom window. Turns around—

The pen had fallen from my hand, making droplets of light, flinty brown on the green carpet. I dived into my den and buried myself beneath the blankets. I stayed in the dark, warm cocoon, running my fingers around the buttons on Mum’s cardigan and smelling the rose scent.

Finally, I crawled out and peeped outside my window. The Dark Blue Baseball Cap Man had gone. 6.14 p.m. I know, because I had double-checked on both my watch and the bedside clock. It’s important to be precise about the details.

I have to record the rest now, one hour and forty-two minutes later at 7.56 p.m., otherwise I’ll never be able to sleep, knowing my records are incomplete. I pick up the blue fountain pen I keep at the side of my bed and start the sentence again. It looks better that way, when my handwriting isn’t panicking and attempting to run off the page. I write:

5.43 p.m. – Dark Blue Baseball Cap Man walks backwards down path, staring up at Bee’s bedroom window. Turns around and sees me watching him with binoculars. He strides towards our house.

?????????????????????????????????

6.14 p.m. – Dark Blue Baseball Cap Man gone.

What happened while I hid for thirty-one minutes in my den? I can’t answer the thirty-three question marks I’ve jotted down.

Did the Dark Blue Baseball Cap Man plan to confront me about my snooping then change his mind? I didn’t hear Dad open the front door. I’d stuck my hands over my ears and sung Taylor Swift’s ‘Bad Blood’ loudly. Still, I’d have heard, wouldn’t I? I’d have seen dark brown shapes, the rapping on our front door.

I’d have heard the colour of voices.

I update my notes:

Who was Dark Blue Baseball Cap Man and what did he want with Bee Larkham?

TUESDAY (BOTTLE GREEN)

Still That Evening

AFTER UPDATING MY RECORDS, I push the notebook beneath my pillow and return to tracing my finger over the male parakeet photo. I don’t want to think about the Dark Blue Baseball Cap Man. I may get nightmares again and they hurt my tummy even when I’ve taken Dad’s painkillers.

I don’t want to think about the blood either, but I can’t help worrying. It hasn’t gone away. Dad’s probably stuffed the knife and my clothes from Friday night behind the lawnmower in the shed at the bottom of our garden. That’s where he hides the sneaky contraband he thinks I don’t know about – emergency packets of cigarettes even though he’s supposed to have given up smoking.

‘Everything OK in here?’ Muddy ochre.

The encyclopaedia tries to escape off my duvet. I manage to catch it in time, ramming my elbow on the pillow to protect my notes. Dad mustn’t find out I’m continuing to make records; I’m keeping secrets. He won’t like to hear about the things I’m remembering.

It’s 7.59 p.m. Dad’s come to say goodnight earlier than usual. A new episode of Criminal Minds must be about to begin on TV.

‘It’s been a tough day, but it’s over now,’ he says. ‘I don’t want you to get worked up about the police. I’ve spoken to DC Chamberlain this evening and taken care of everything. Bee’s someone else’s problem now, not ours.’

I concentrate on the parakeet photos.

‘What about her body?’

Dad sucks in his breath with smoky ochre wisps. ‘We’ve been through this a million times. I sorted everything with Bee. You can stop worrying about her.’

‘But—’

‘Look, I’m telling you she’s not going to bother either of us again. I promise you.’

Silence. No colour.

‘Jasper? Are you still with me?’

‘Yeah. Still here.’ Unfortunately. I wish I wasn’t. I wish I could be a parakeet snuggled deep in the nest in the oak tree over the road. I bet it’s cosy. It used to be a woodpeckers’ nest after the squirrels left, but the parakeets took over the old drey. They always force out other nesting birds like nuthatches, David Gilbert said.

‘Jasper. Look at me and focus on my face. Concentrate on what I’m about to say.’

Don’t want to.

I drag my gaze away from the book in case Dad tries to take that away as well as the bag of seed. I pull his features into a concise picture inside my head – the blue-grey eyes, largish nose and thin lips. I close my eyes and the image vanishes again like I’d never drawn it.

‘Open your eyes, Jasper.’

I do as I’m told and Dad reappears as if by magic. His voice helps. Muddy ochre.

‘I’ve told you already, the police aren’t going to find Bee’s body because there’s no body to find.’

Now it’s my turn to make a funny sucking in colour with my breath. It’s a darker, steelier blue than before.

He’s trying to distance us both from what happened in Bee Larkham’s kitchen on Friday night. Maybe he thinks Rusty Chrome Orange has bugged my bedroom. He could have planted listening devices throughout the whole house. The police do that all the time on Law & Order.

I picture a dark van parked outside our house – two men inside, headphones clamped to their ears, listening to Dad and me talking, hoping we’ll let slip something incriminating about Bee Larkham.

I have to stick to our story.

There is no body.

I repeat the words under my breath.

The police can’t find Bee Larkham’s body if they don’t look for the body and the police aren’t looking for the body, dense Rusty Chrome Orange has proven that. He’s trampled over the Hansel-and-Gretel-style trail of crumbs I left for him, never noticing they lead to the back door of Bee Larkham’s house. They continue into her kitchen and stop abruptly.

I don’t know where the crumbs reappear. Dad hasn’t told me what happened after I fled the scene. Her body could rot for months before it’s found.

If it’s ever found.

There’s no body to find.

‘OK, Dad. If you’re sure about this?’

‘I am. Stay away from Bee’s house and stop talking about her. I don’t want to hear you mention her name again. I want you to forget about her and forget what happened between the two of you on Friday night. No good can come from talking about it.’

I move my head up and down.

Dad’s supposed to know best because he says he’s older and wiser than me. The problem is, whatever Dad claims, it still feels wrong.

I pull out a photo from beneath the book on my bedside table. It’s a new one. Not new, as in someone just took a picture of Mum, which would be impossible. She died when I was nine. I wasn’t allowed to go to the funeral because Dad said I’d find it too upsetting. I haven’t seen this photo before – not in the albums or in his bedside drawer. I found it at the back of the filing cabinet in his study.

I stare at the six people standing in a line. ‘Which one’s Mum?’

‘What?’ Dad’s checking his watch. I’m keeping him from important FBI business. The plots are complicated. He’ll never catch up.

‘Which one’s my mum?’ I repeat. ‘In this photo?’

‘Let me see that.’

I hold the picture up but don’t let him take it off me. He might leave a smudgy fingerprint, which would ruin it.

‘God, I haven’t seen that photo in years. Where did you find it?’

‘Er, um.’ I don’t want to admit I’ve been rummaging in his filing cabinet again and the drawers in his study.

After the parakeets and painting, my next favourite hobby is rooting through all Dad’s stuff when he’s not around.

‘It was stuck behind another photo in the album.’ It’s only a small lie in the grand scheme of things.

Dad’s eyebrows join together at the centre. ‘Wow. This brings back memories. It’s Nan’s seventy-fifth birthday party.’

Interesting, but he hasn’t answered my question.

‘Which woman is Mum?’

He sighs, smooth light ochre button shapes. ‘You honestly don’t know?’

‘I’m tired. I can’t concentrate properly.’ It’s that useful lie again, a trusty friend, like dusky pink number six.

‘She’s that one,’ he says, pointing. ‘At the far right of the photograph.’

‘She’s the woman in the blue blouse with her arms around that boy’s shoulders.’ I repeat it to myself to help memorize her position in the photo.

‘Your shoulders. She’s hugging you. You’re both smiling at the camera.’

I stare at the strangers’ faces.

‘Who’s that?’ I point at another woman, further along. She’s also wearing a blue top, which is confusing.

‘That was your nan. She passed away a month …’ His muddy ochre voice trails away.

I finish the sentence for him. ‘A month after Mum died. Her heart stopped beating from the grief and shock of losing her only daughter.’

Dad inhales sharply. ‘Yes.’ His word’s a jagged arrow, whistling through the air.

I bat away his unprovoked attack. ‘She knew she couldn’t replace Mum. That would have been impossible.’

‘Of course she couldn’t replace Mum. You can’t replace people, like possessions. Life doesn’t work like that, Jasper. You understand that, right?’

Deep down, he must know he’s a liar, but I don’t want to think about that now.

‘What colour was Mum’s voice?’ I say, changing the subject.

Dad checks his watch again. He should have pressed ‘pause’ on the remote before he came up to say goodnight. He’s missed six minutes and twenty-nine seconds of Criminal Minds. A serial killer has probably struck already.

‘You know what colour she was. It’s the colour you always say she was.’

‘Cobalt blue.’ I pinch my eyes shut, the way I did in the police station. It doesn’t work. I open my eyes and stare at my paintings. I’ve lined them up under the windowsill, below my binoculars. They stare back accusingly.

‘Mum’s cobalt blue. That’s what I want to remember about her. Shimmering ribbons of cobalt blue.’

‘That’s her colour,’ Dad says. ‘Blue.’

‘Was she? Was she definitely cobalt blue?’

His shoulders rise and fall. ‘I have no idea. When Mum spoke, I saw …’

‘What?’ I bite my lip, waiting. ‘What did you see?’

‘Just Mum. No colour. She looked normal to me. The way she looked normal to everyone else. Everyone apart from you, Jasper.’

He turns away, but I can’t let Mum’s colour go.

‘I used to talk about Mum being cobalt blue when I was little?’ I press. ‘I never mentioned another shade of blue? Like cerulean?’

‘Let’s not do this now. It’s late. You’re tired. I’m beat too.’

He means he doesn’t want to talk about my colours again. He wants me to pretend I see the world like he does, monochrome and muted. Normal.

‘This is important. I have to know I’m right.’ I kick off the duvet, which is strangling my feet.

‘What am I thinking? Of course she was cobalt blue.’ Dad’s voice is light enough to be swept away by a gentle summer breeze. ‘Don’t get het up about this before bedtime. You need to go to sleep. It’s school tomorrow and I’ve got work. I can’t take another day off. You have to stop thinking about Bee and start concentrating on school. Your stomach looks a lot better, but you need to get your head straight. OK?’

He comes back, leans down and kisses my forehead. ‘Good night, Jasper.’

Four large strides and Dad’s at the door. He closes it to the usual gap of exactly three inches.

He’s told yet another lie.

This isn’t a good night. Far from it.

I wait until I hear the dark maroon creak of the leather armchair in the sitting room before I leap out of bed and snatch up the paintings of Mum’s voice again.

Her exact shade of cobalt blue doesn’t come ready-mixed in a tube. It has to be created. I’ve tried to change the tint by adding white and mixed in black to alter the shade, but everything I attempt is wrong.

If these pieces of art are misleading me, are my other paintings a series of lies too? I sift through the boxes in my wardrobe and retrieve all the paintings from the day Bee Larkham first arrived and onwards. There are seventy-seven in total, which I sort into categories: the parakeets; other bird songs; Bee’s music lessons; everyday sounds.

I’m not worried about these pictures. Their colours can’t harm me.

Not like the voices, which I arrange into separate piles to study their colours in more detail: Bee Larkham. Dad. Lucas Drury. The neighbours.

All the main players.

I painted them to help remember their faces.

Some paintings refuse to get into order. The colours of conversations bleed into each other and transform into completely different hues.

That’s when I finally see what was never clear before. It’s where my problems began and it’s why I can’t get Mum’s voice 100 per cent right: I no longer know which voice colours are right and true, which are tricking me and which are downright liars.

I need to start again. I’ll never know what happened unless I get them right. Until I sort the good colours from the bad.

I wet a large brush and mix cadmium yellow with alizarin crimson paint on my palette.

I feel calmer and stronger. I’m in control. I’m going to paint this story from the beginning – from 17 January – the day it began. My first painting is called: Blood Orange Attacks Brilliant Blue and Violet Circles on canvas.

I will force the colours to tell the truth.

One brushstroke at a time.

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.