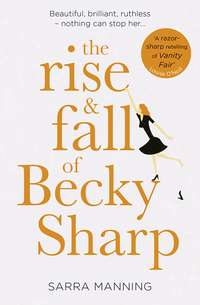

Kitabı oku: «The Rise and Fall of Becky Sharp: ‘A razor-sharp retelling of Vanity Fair’ Louise O’Neill», sayfa 2

While Babs was gasping like a landlocked fish at that sheer audacity, Becky happened to mention that the press might be quite interested to know that a large standing order on Jemima’s account was paid to Babs every month. ‘Though it’s not like you’ve been busy finding her work. And Jemima was beloved of so many that I think people might get quite cross if they thought that she was being taken advantage of by her niece, who also happened to be her agent.’

‘Or by the common little tart that’s been living off Jemima for the last four years,’ Babs countered, and Becky was old enough and big enough now that when Babs’ hand crept up to take hold of her cheek in a bruising grip, she knocked her hand away.

‘I’m not a common little tart,’ she corrected. ‘I’m a poor little orphan devoted to Jemima. The granddaughter she never had, that’s what Reverend Squills used to say when he invited us over for Sunday lunch. Towards the end, you see, Jemima found God …’

Babs Pinkerton snorted in derision at such a notion.

‘… Anyway, we were quite regular churchgoers so I’m sure the Reverend would be happy to defend me. He’s got quite a taste for publicity. It’s hard to keep him out of the local paper banging on about the gangs of feckless youths hanging about on the seafront. I can’t even imagine his reaction if the nationals started sniffing about …’

‘What do you want?’ Babs had asked thinly.

A modest sum from the eventual sale of the bungalow, the right to keep any mementos – for instance, any jewellery that Becky might just happen to find when she was clearing out the bungalow – and some insurance against the future.

‘I’ve been stagnating in Southbourne for the last four years, so what now?’ she demanded of Babs who’d taken command of Jemima’s favourite easy chair and a very large gin, easy on the tonic. ‘I don’t have a qualification to my name and I can’t really see the point of toiling away at evening classes just so I can end up working in a call centre.’

Barbara had raised one over-plucked eyebrow. ‘The world needs people to work in call centres. Natural selection and all that.’

‘We can do better than a call centre. These …’ Becky gestured at her breasts, ‘her famous frontal development’, as they were described by the good Reverend, who wasn’t as godly as his venerated status suggested. Not when he was chasing Becky around the vestry with an avaricious gleam in his eyes. ‘And this …’ she pointed at her pretty face, her slanting green eyes and defined cheekbones giving her an almost feline, feral look, ‘and this …’ she tapped her head, ‘would be wasted on people wanting to change their internet service provider. You have contacts and connections. You can make me famous!’

Although Becky couldn’t sing or dance, her dramatic talents clearly weren’t in any doubt. If Babs could turn the girl into a meal ticket rather than a thorn in her side and collect her 20 per cent commission, then it would be win/win. Babs knew a producer at a production company who owed her a rather large favour and so eight weeks ago, Becky had entered the Big Brother house.

‘The rest is up to you,’ Babs had said.

Now, Babs placed a consoling, pink-taloned hand on Becky’s arm. ‘Even though technically you’re a loser, there’s still some serious money to be made before your meter runs out,’ she said. ‘We have a golden window right now. I’d make the most of all those personal-appearance fees to press the flesh at suburban nightclubs. Then we can get you at least ten thousand to appear in one of the Sunday tabs in your undies to spin some sob story about your dear departed ma and pa. We might even be able to bag you a footballer. Not Premier League but definitely First Division.’

What was that unpleasant sound in Becky’s ear? Ah yes, the bottom of the barrel being scraped.

‘I didn’t spend eight weeks locked in a house with a bunch of vacuous morons to get my tits out for the Sunday People and then disappear. Have you any idea what I’ve been through, Babs? There were times when I had to lock myself in the toilet and bite my hand towel to stop myself from screaming.’

‘They were a particularly sorry bunch this year.’ Babs’ eyes narrowed. ‘But if you were to get your knockers out, I could probably get you a few more thousand.’

There was a commotion at the other end of the bar as the more worthy, though far less deserving winner, entered the room. Amelia was with her mother and father, both of them tall and rangy, fair of hair and face. Amelia had told Becky that her father managed a hedge fund, and that her mother was the daughter of a man who’d made his fortune in plumbing supplies. Rich enough that home was a six-bedroom townhouse in Kensington and a pretty, ivy-strewn manor house in Oxfordshire. Rich enough that Mr and Mrs Sedley both had a set expression as if they were clenching their jaws and trying not to breathe in the smell of fried food, air freshener and cheap white wine that permeated the bar of the Elstree hotel.

There was no sign of Amelia’s Eton-educated brother who did something lucrative with energy drinks but there were a man and woman bringing up the rear, the man clamped to his mobile phone, the woman clamped to two mobile phones. It was clear that Amelia’s agent and publicist were cut from a very different cloth to Babs Pinkerton.

‘I don’t just want “a few more thousand”. I want more,’ Becky said to Babs Pinkerton, as she caught Amelia’s eye. The other girl smiled, waved enthusiastically and beckoned Becky over: but she wasn’t going to hurry to Amelia, like an obedient little pet dog.

‘More what? More money? Your boobs aren’t that great, Becky,’ Babs said witheringly. ‘And don’t start thinking that another agent will get you more cash – they won’t. They’d tell you the exact same thing and anyway, you signed an exclusive contract with me.’

That was a lesson learned the hard way: never sign anything. And no, it wasn’t just more money. Or more time in the spotlight.

It was more everything.

Amelia detached herself from the adoring throng that had congregated around her and hurried over to the corner where Becky and Babs were still in their unhappy huddle, followed by her anxious-looking Mama and publicist.

‘Becky!’ Amelia seized her hands and hauled her up. ‘I can’t wait for you to meet Mummy! I know you two are going to be best friends.’

From the pained and furrowed brow of Mrs Sedley, Becky very much doubted it. ‘It’s so lovely to meet you, Mrs Sedley,’ she said politely and as Mrs Sedley unwillingly leaned forward a scant five degrees for an air kiss, Becky held out her hand instead, to the other woman’s evident surprise and gratitude.

Then Becky made sure the handshake was brisk, firm but not too firm.

‘Rebecca, congratulations on doing so well in the house,’ Mrs Sedley said tightly.

‘I wouldn’t have lasted five minutes in there without Emmy,’ Becky said, resting her head on Amelia’s shoulder. ‘She was an absolute lifesaver.’

‘I think you have that the wrong way round,’ Amelia said, putting her arm round Becky’s waist. ‘Come and sit with us.’

‘No, you must have so many people wanting to talk to you, I don’t want to intrude,’ Becky said, as she heard another one of Barbara Pinkerton’s snorts from behind her as her erstwhile mentor levered herself off the banquette.

‘When you’ve stopped having notions, you know where to find me,’ Babs muttered as she pushed past Becky who was giving her full attention to Amelia and Mrs Sedley, so that even in the muted lighting of the bar, they’d be able to see the slightly forlorn expression on her face before she gave them a brilliant smile that drooped ever so slightly at the edges.

‘Honestly, Emmy, after eight weeks you must be sick to death of me,’ Becky said with a self-deprecating little laugh. ‘I know how close you are to your mother, how much you must have to catch up on.’ She ended on a wistful little sigh.

‘Oh, Becky! And you don’t have anybody,’ Amelia exclaimed, the arm round Becky’s waist tightening. ‘You don’t even have anywhere to call home now we’re out of the house.’

‘Is that true?’ Mrs Sedley asked. ‘Are you homeless?’

‘Homeless’ had all sorts of unpleasant connotations even if technically it was true. ‘I was a live-in care assistant before Big Brother but the lovely lady I was looking after – she was like a grandmother to me – well, she died.’

Becky had mentioned this on the show. Just the once. To Carlo and Amelia (and three million viewers) but Amelia’s eyes filled with tears. ‘Oh, Becky …’

‘I’ll be all right,’ Becky insisted, squaring her shoulders and raising her chin but it was just a momentary act of bravado and then she drooped again. ‘Babs, my agent, says I can make some money if I agree to pose topless but I don’t think that I want to do that. I’m sure something else will turn up and in the meantime, I just have to look on the bright side. Like, I can’t be homeless because I’m booked in here for the night.’ Becky caught her bottom lip between her teeth and looked off to the side. ‘I’m sure I could extend my stay. It can’t be that expensive. It’s not a particularly grand hotel, is it?’

‘It’s an awful hotel. They have pot-pourri in the ladies’ bathrooms,’ Mrs Sedley said from between gritted teeth, as if, of all the indignities heaped on her by her daughter appearing on a reality TV show, pot pourri in the ladies’ loos was the very final straw. ‘I’m sure Emmy would never forgive me if I didn’t insist that you come and stay with us, for a week or so, until you’ve made other arrangements.’

‘I really wouldn’t want to impose.’ Becky lifted her chin again, even as her bottom lip trembled. ‘I can look after myself.’

‘Only because you’ve never had any other option,’ Amelia said, tucking her arm through Becky’s. ‘You haven’t even met Rhoda, my publicist, yet,’ she added, gesturing at the woman hovering next to them, who was in a sleek black suit with a sleek black bob to match and looked as if she had all sorts of useful contacts and strategies to ensure that her clients (and potential clients) could forge long, successful careers without having to flash their breasts to the readers of a downmarket Sunday tabloid. ‘She wants me to do all sorts of things. TV and radio interviews. Photo shoots. It all sounds terrifying but it wouldn’t be so terrifying if we did them together.’

‘Well, I suppose … If I could help out … then I wouldn’t feel quite so bad about imposing,’ Becky decided. ‘And as soon as I’ve outstayed my welcome, you’re to let me know and I’ll pack my bags. I mean, I hardly have anything in the way of bags, but you know what I mean.’

‘You can stay as long as you want,’ Amelia promised rashly. ‘Now, let’s get out of here. The smell of fried food is making me feel nauseous.’

Chapter 4

Emmy Sedley @Amelia_SedleyBB

Becky and I are on our way to This Morning to chat to Phillip Schofield and Holly Willoughby! #BFF #bliss #humble #teamworkmakesthedreamwork

The Sedleys’ London residence (because any house with a staff annexe and its own sauna and steam room counted as a residence) was in Kensington. On the wrong side of the park, because no matter how many millions Mr Sedley had made from hedging funds and gilt-edging futures, the family weren’t old money. Only old money and the very newest money could afford the right side of the park.

But as Becky was shown into a pretty guestroom, decorated in white and a delicate pale green, with its own en suite bathroom, she decided that it would do very nicely indeed.

She hadn’t been exaggerating for dramatic effect when she’d told Amelia that she didn’t have much in the way of bags. Baggage, perhaps, but that was another matter. All her worldly possessions fitted into her Big Brother suitcase, a shabby black holdall and a checked laundry bag.

Amelia swept into the guest room the next day to be confronted by the sorry state of Becky’s goods and chattels and the even sorrier state of Becky’s wardrobe. There hadn’t been much call for anything other than jeans and a jumper when she was tending to Jemima Pinkerton and the only man she regularly came into contact with was Reverend Squills. No wonder Amelia’s mouth and china-blue eyes had become three perfect circles of horror.

‘Oh dear,’ she said. ‘Oh, Becky. Oh no.’ Then she swept out again.

She was back not even ten minutes later, her arms full of clothes. ‘No, Emmy, absolutely not!’ Becky said, from the doorway of the en suite. She was swathed in a fluffy white towelling robe, her hair hidden by another towel so that she looked all eyes and cheekbones. ‘I have my own clothes. They’re not as nice as yours, but they’ll do.’

‘These are all too small for me,’ Amelia insisted, having spent a lot of time in the Big Brother house comfort eating. Mrs Sedley had remarked on the way home last night that Amelia would have to go on a juice fast immediately.

‘It goes straight to your face, Emmy,’ she’d said with some concern. ‘We were quite shocked at how puffy you looked in the last week on that show.’

Now Amelia held up a floral dress. ‘I bought this after I came back from Niger. It fitted me for two weeks and now it’s just taking up wardrobe space.’ Then a pair of designer jeans. ‘I’ve never been able to get into these. Bought them online from Net-a-Porter and never got round to returning them.’ Next a grey cashmere jumper was lifted up for Becky’s inspection. ‘Grey completely washes me out but you can wear pretty much anything.’

‘Not anything,’ Becky disagreed, creeping forward to touch the luxurious soft pile of the grey cashmere as if she couldn’t help herself. ‘Oh, I’ve never felt anything so soft.’

‘And Jos – my brother, Jos, you’ll meet him soon – sent over some workout gear. He’s booked me a personal trainer too. Said he can’t have a lardy sister …’

‘It must be delightful to have a brother like that,’ Becky murmured as she held up a navy-blue designer dress which would be perfect for her TV appearance that morning.

‘He is delightful,’ Amelia agreed, because she never had a bad word to say about anyone. It grew quite tiresome after a while. ‘Except, I feel as if I hardly know him. He’s ten years older than I am so he was at school when I was growing up and then he went to LA after university … LA is so far away and he has rather taken to the lifestyle.’

‘Oh? Is his wife from LA too?’ Becky asked as she wriggled into the navy-blue dress.

‘No, Jos isn’t married,’ Amelia assured her. ‘He says that there’s no way he could have built up the second-largest protein-ball business on the West Coast if he’d prioritised relationships. He also said that he wasn’t going to get married until he was thirty-five so we tease him that he’s only got three years left to find a wife. Oh, Becky! That dress looks so much better on you than it ever did on me.’

‘I’m sure it doesn’t,’ Becky said automatically but later on, in front of the TV cameras, Becky’s navy-blue hand-me-down really made her skin and hair pop whereas the cream blouse Amelia wore put at least ten pounds on her and, despite the best efforts of the make-up department, seemed to blend into her skin tone in the most unflattering way.

The day passed in a blur of TV-studio and radio-station green rooms. Nobody was pleased that Becky was there too, like a free gift with the booking of the latest Big Brother winner. Amelia’s publicist, Rhoda, even suggested that Becky wait in the car and Becky really didn’t want to get in anyone’s way (‘honestly I don’t, but Emmy, you’re shaking. Shall I come and sit with you while you wait to go on?’).

When it quickly became clear that Amelia only made good TV when she was crying, Becky was no longer the spectre at the feast. On the contrary, she soon had joint billing and it turned out she was a natural for live TV and radio, with an endless supply of amusing anecdotes about life in the house, all good to go. ‘No one could get to sleep for the smell, could we, Emmy?’ she recalled as she sat side by side with Amelia on the This Morning sofa.

‘No. It was a very bad smell.’

‘Finally we tracked it down to a rancid mug of soup that Johnny had left under his bed that had attracted maggots, and they made us stay in the garden while the fumigators dealt with it.’

‘And it was raining,’ Amelia added timidly.

‘Pouring with rain,’ Becky elaborated. ‘And that’s why I’m never going to eat mushroom soup for as long as I live.’ She paused. ‘At least Johnny swore it was mushroom soup but we all had our suspicions, didn’t we?’

‘Did we? But what else could it have been?’ Amelia’s face was absolutely without guile as Phil and Holly hooted with laughter.

They ended the day at a shoot and interview for Hello magazine shot in a location house in Clapham, because Mrs Sedley absolutely wasn’t going to have people tramping in and out of her house with equipment when she’d just had the parquet flooring redone. (She was also quite terrified that her choice of soft furnishings wouldn’t pass muster because she’d insisted on doing the decorating herself even though Mr Sedley had begged her to hire an interior designer.)

The journalist was blonde and perky and cut from the same cloth as Amelia who happily reeled off her list of achievements to date. The Chelsea prep school where she graduated, being able to speak German and Mandarin (though neither of them had stuck). She’d then attended the same boarding school as the Duchess of Cambridge where she failed to excel academically but had won a trophy for tennis. Only two hardships had blighted Amelia’s life to date: her sluggish metabolism which meant that the only way she could maintain a size-ten figure was by eating twelve hundred calories a day and working out for an hour, and the three years she’d spent sleeping in a back brace to improve her posture.

‘Daddy and Jos always used to joke that it was because I had no backbone,’ she admitted with a nervous giggle. And of course there was the measly two weeks that Amelia had spent doing volunteer work in Niger.

‘Like Princess Diana,’ the journalist, Emily, noted dryly. ‘Were you worried about catching something awful like yellow fever or malaria?’

‘Not quite like Princess Diana. I mean, there were no landmines and we had WiFi,’ Amelia said. ‘But I did have to have a lot of jabs before I went. My arm was sore for days afterwards.’

On the other hand, Becky’s biography was quite sparse. It was also quite hard to remember what she’d told people in the Big Brother house. Another lesson learnt: come up with a story then stick to it as if your life depended on it.

‘My father was an artist,’ she recalled with a misty look to her eye, because to be fair, some of his scams really had possessed quite a lot of artistry. The judge who’d sent him down had described him as ‘a curious mixture of criminal genius and petty thief with poor impulse control.’ ‘Everyone said that he was destined for greatness but he died before greatness came.’

‘And, I understand how hard this must be for you, but how did he die?’

Becky cast her eyes down. ‘He had a brief but brave fight against a cruel disease.’ When she said that people always assumed that it was cancer and that she’d been at her father’s side as he was carried away by the angels. The ugly truth of the matter was that it had been cirrhosis of the liver and the only person at his side had been a prison chaplain, as Francis Henry Sharp had been serving seven years at Her Majesty’s Pleasure for five counts of fraud and one count of ABH for breaking the nose of the arresting officer.

Next to her, Amelia snivelled a little and the journalist leaned closer. ‘And your mother died when you were still quite young?’

Becky did her best brave face. Downcast eyes, a little half-smile, a sudden intake of breath as if she was fighting to control herself. ‘Yes, by the time I was eight, it was just Daddy and me. I’m sorry, can I have a moment?’

‘It’s very painful for Becky to talk about,’ Amelia whispered, taking hold of Becky’s hand as if she could loan her friend some of her own meagre courage. ‘Are you OK to carry on? Do you want some water?’

An intern was despatched to bring Becky water. Sparkling water in a cut-glass tumbler with crushed ice and a big chunk of lime.

Who could blame a girl for not wanting to go back to a life where there was only tap water in any receptacle that was vaguely clean?

‘Your mother?’ Emily prompted. ‘You said in the house that she was French.’

‘Mais oui, maman etait francaise. She came from a very old family, the Mortmerencys, and she was a model. No! You wouldn’t have heard of her. She did a little catwalk, but mostly fit work,’ Becky explained, though the closest her mother had come to the catwalk was draping herself over the bonnet of a Ford Fiesta at a motoring exhibition at Olympia. She had been quite pretty before the booze and the pills and the putting up with Frank Sharp had taken their toll on her. ‘Her passing was very sudden.’

Hurling yourself in front of the 7.08 District Line train pulling into Fulham Broadway station didn’t lend itself to a long, lingering death.

‘Oh, Becky,’ both Amelia and Emily exclaimed.

‘Sorry, it’s just that it’s painful to talk about.’

Had it been painful at the time? Becky could hardly remember. Sidonie had barely fulfilled her job description. She swung from high to low, as Mr Sharp had vacillated from sweet to mean, so from a very young age, Becky had learned to keep her head down, stay out of the line of fire, especially when her parents had fought, which they did with intense ferocity. If that was love, then you could shove it.

‘So, Becky, let’s switch it up, shall we?’ Emily asked.

Becky clapped her hands together. ‘God, yes, please, let’s!’

Where had she gone to school?

School of hard knocks.

Had she had many boyfriends?

Only if you count a Bournemouth vicar who used to try to put his hand up my skirt when I was helping with the church jumble sale.

Who were her celebrity crushes?

What would be the point of having a crush on some distant celebrity who would be of absolutely no use to me?

Dear, sweet Emily and her voice recorder would probably both short circuit if Becky told them a few home truths, so she settled for the current truth and put her arm around Amelia.

‘I’m just here for moral support. Emmy’s the star and so she’s the one you should be asking about boyfriends and crushes.’ Becky nudged Amelia who giggled obligingly.

‘There is someone,’ Emmy confided, because it never occurred to her that she could fudge the details, hint, or stretch, bend and pull the truth this way and that, so it hardly even resembled the truth any more. ‘I’ve known him all my life, he was at school with my brother Jos, so I’m sure he thinks I’m still the silly little girl that he always teased.’

Such a cliché. The haughty older boy who …

‘… used to pull my pigtails.’

Even Emily was starting to look as if her back teeth were aching from Amelia’s brand of simpering, saccharine sweetness.

‘And does this someone have a name?’ Emily asked with the weary air of a woman who had an Oxbridge degree and a childhood ambition to be a lady war correspondent, but was currently interviewing the winner (and runner-up!) of a reality TV show.

Amelia ducked her hair. ‘George,’ she said on a gasp, as if even saying his name out loud was tempting fate. ‘His name is George.’