Kitap dosya olarak indirilemez ancak uygulamamız üzerinden veya online olarak web sitemizden okunabilir.

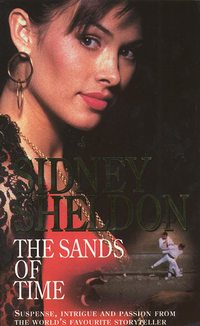

Kitabı oku: «The Sands of Time», sayfa 2

Chapter Three

Ávila

The silence was like a gentle snowfall, soft and hushed, as soothing as the whisper of a summer wind, as quiet as the passage of stars. The Cistercian Convent of the Strict Observance lay outside the walled town of Ávila, the highest city in Spain, 112 kilometres north-west of Madrid. The convent had been built for silence. The rules had been adopted in 1601 and remained unchanged through the centuries: liturgy, spiritual exercise, strict enclosure, penance and silence. Always the silence.

The convent was a simple, four-sided group of rough stone buildings around a cloister dominated by the church. Around the central court the open arches allowed the light to pour in on the broad flagstones of the floor where the nuns glided noiselessly by. There were forty nuns at the convent, praying in the church and living in the cloister. The convent at Ávila was one of seven left in Spain, a survivor out of hundreds that had been destroyed by the Civil War in one of the periodic anti-Church movements that took place in Spain over the centuries.

The Cistercian Convent of the Strict Observance was devoted solely to a life of prayer. It was a place without seasons or time and those who entered were forever removed from the outside world. The Cistercian life was contemplative and penitential; the divine office was recited daily and enclosure was complete and permanent.

All the sisters dressed identically, and their clothing, like everything else in the convent, was touched by the symbolism of centuries. The capucha, the cloak and hood, symbolized innocence and simplicity, the linen tunic the renouncement of the works of the world, and mortification, the scapular, the small squares of woollen cloth worn over the shoulders, the willingness to labour. A wimple, a covering of linen laid in plaits over the head and around the chin, sides of the face and neck, completed the habit.

Inside the walls of the convent was a system of internal passageways and staircases linking the dining room, community room, the cells and the chapel, and everywhere there was an atmosphere of cold, clean spaciousness. Thick-paned latticed windows overlooked a high-walled garden. Every window was covered with iron bars and was above the line of vision, so that there would be no outside distractions. The refectory, the dining hall, was long and austere, its windows shuttered and curtained. The candles in the ancient candlesticks cast evocative shadows on the ceilings and walls.

In four hundred years nothing inside the walls of the convent had changed, except the faces. The sisters had no personal possessions, for they desired to be poor, emulating the poverty of Christ. The church itself was bare of ornaments, save for a priceless solid gold cross that had been a long-ago gift from a wealthy postulant. Because it was so out of keeping with the austerity of the order, it was kept hidden away in a cabinet in the refectory. A plain, wooden cross hung at the altar of the church.

The women who shared their lives with the Lord lived together, worked together, ate together and prayed together, yet they never touched and never spoke. The only exception permitted was when they heard mass or when the Reverend Mother Prioress Betina addressed them in the privacy of her office. Even then, an ancient sign language was used as much as possible.

The Reverend Mother was a religieuse in her seventies, a bright-faced robin of a woman, cheerful and energetic, who gloried in the peace and joy of convent life, and of a life devoted to God. Fiercely protective of her nuns, she felt more pain when it was necessary to enforce discipline, than did the one being punished.

The nuns walked through the cloisters and corridors with downcast eyes, hands folded in their sleeves at breast level, passing and re-passing their sisters without a word or sign of recognition. The only voice of the convent was its bells – the bells that Victor Hugo called ‘the Opera of the Steeples’.

The sisters came from disparate backgrounds and from many different countries. Their families were aristocrats, farmers, soldiers … They had come to the convent as rich and poor, educated and ignorant, miserable and exalted, but now they were one in the eyes of God, united in their desire for eternal marriage to Jesus.

The living conditions in the convent were spartan. In winter the cold was knifing, and a chill, pale light filtered in through leaded windows. The nuns slept fully dressed on pallets of straw, covered with rough woollen sheets, each in her tiny cell, furnished only with a straight-backed wooden chair. There was no washstand. A small earthenware jug and basin stood in a corner on the floor. No nun was ever permitted to enter the cell of another, except for the Reverend Mother Betina. There was no recreation of any kind, only work and prayers. There were work areas for knitting, book binding, weaving and making bread. There were eight hours of prayer each day: Matins, Lauds, Prime, Terce, Sext, None, Vespers and Compline. Besides these there were other devotions: benedictions, hymns and litanies.

Matins were said when half the world was asleep and the other half was absorbed in sin.

Lauds, the office of daybreak, followed Matins, and the rising sun was hailed as the figure of Christ triumphant and glorified.

Prime was the church’s morning prayer, asking for the blessings on the work of the day.

Terce was at nine o’clock in the morning, consecrated by St Augustine to the Holy Spirit.

Sext was at 11.30 a.m., evoked to quench the heat of human passions.

None was silently recited at three in the afternoon, the hour of Christ’s death.

Vespers was the evening service of the church, as Lauds was her daybreak prayer.

Compline was the completion of the Little Hours of the day. A form of night prayers, a preparation for death as well as sleep, ending the day on a note of loving submission: Manus tuas, domine, commendo spiritum meum. Redemisti nos, domine, deus, veritatis.

In some of the other orders, flagellation had been stopped, but in the cloistered Cistercian convents and monasteries it survived. At least once a week, and sometimes every day, the nuns punished their bodies with the Discipline, a twelve-inch long whip of thin waxed cord with six knotted tails that brought agonizing pain, and was used to lash the back, legs and buttocks. Bernard of Clairvaux, the ascetic abbot of the Cistercians, had admonished: ‘The body of Christ is crushed … our bodies must be conformed to the likeness of our Lord’s wounded body.’

It was a life more austere than in any prison, yet the inmates lived in an ecstasy such as they had never known in the outside world. They had renounced physical love, possessions and freedom of choice, but in giving up those things they had also renounced greed and competition, hatred and envy, and all the pressures and temptations that the outside world imposed. Inside the convent reigned an all-pervading peace and the ineffable sense of joy at being one with God. There was an indescribable serenity within the walls of the convent and in the hearts of those who lived there. If the convent was a prison, it was a prison in God’s Eden, with the knowledge of a happy eternity for those who had freely chosen to be there and to remain there.

Sister Lucia was awakened by the tolling of the convent bell. She opened her eyes, startled and disoriented for an instant. The little cell she slept in was dismally black. The sound of the bell told her that it was 3.00 a.m., when the office of vigils began, while the world was still in darkness.

Shit! This routine is going to kill me, Sister Lucia thought.

She lay back on her tiny, uncomfortable cot, desperate for a cigarette. Reluctantly, she dragged herself out of bed. The heavy habit she wore and slept in rubbed against her sensitive skin like sandpaper. She thought of all the beautiful designer gowns hanging in her apartment in Rome and at her chalet in Gstaad. The Valentinos and Armanis and Giannis.

From outside her cell Sister Lucia could hear the soft, swishing movement of the nuns as they gathered in the passage. Carelessly, she made up her bed and stepped out into the long corridor, where the nuns were lining up, eyes downcast. Slowly, they all began to move towards the chapel.

They look like a bunch of penguins, Sister Lucia thought. It was beyond her comprehension why these women had deliberately thrown away their lives, giving up sex, pretty clothes and gourmet food. Without those things, what reason is there to go on living? And the goddamned rules!

When Sister Lucia had first entered the convent, the Reverend Mother had said to her, ‘You must walk with your head bowed. Keep your hands folded under your habit. Take short steps. Walk slowly. You must never make eye contact with any of the other sisters, or even glance at them. You may not speak. Your ears are to hear only God’s words.’

‘Yes, Reverend Mother.’

For the next month Lucia took instruction.

‘Those who come here come not to join others, but to dwell alone with God, solitariamente. Solitude of spirit is essential to a union with God. It is safeguarded by the rules of silence.’

‘Yes, Reverend Mother.’

‘You must always obey the silence of the eyes. Looking into the eyes of others would distract you with useless images.’

‘Yes, Reverend Mother.’

‘The first lesson you will learn here will be to rectify the past, to purge out old habits and worldly inclinations, to blot out every image of the past. You will do purifying penance and mortification to strip yourself of self-will and self-love. It is not enough for us to be sorry for our past offences. Once we discover the infinite beauty and holiness of God, we want to make up not only for our own sins, but for every sin that has ever been committed.

‘Yes, Reverend Mother.’

‘You must struggle with sensuality, what John of the Cross called, “the night of the senses”.’

‘Yes, Reverend Mother.’

‘Each nun lives in silence and in solitude, as though she were already in heaven. In this pure, precious silence for which she hungers, she is able to listen to the infinite silence and possess God.’

At the end of the first month, Lucia took her initial vows. On the day of the ceremony she had her hair shorn. It was a traumatic experience. The Reverend Mother Prioress performed the act herself. She summoned Lucia into her office and motioned for her to sit down. She stepped behind her, and before Lucia knew what was happening, she heard the snip of scissors and felt something tugging at her hair. She started to protest, but she suddenly realized that what was happening could only improve her disguise. I can always let it grow back later, Lucia thought. Meanwhile, I’m going to look like a plucked chicken.

When Lucia returned to the grim cubicle she had been assigned, she thought: This place is a snake pit. The floor consisted of bare boards. The pallet and the hard-backed chair took up most of the room. She was desperate to get hold of a newspaper. Fat chance, she thought. In this place they had never heard of newspapers, let alone radio or television. There were no links to the outside world at all.

But what got on Lucia’s nerves most of all was the unnatural silence. The only communication was through hand signals, and learning those drove her crazy. When she needed a broom, she was taught to move her outstretched right hand from right to left, as though sweeping. When the Reverend Mother was displeased, she brought together the tips of her little fingers three times in front of her body, the other fingers pressing into her palm. When Lucia was slow in doing her work, the Reverend Mother pressed the palm of her right hand against her left shoulder. To reprimand Lucia, she scratched her own cheek near her right ear with all the fingers of her right hand in a downward motion.

For Christ’s sake, Lucia thought, it looks like she’s scratching a flea bite.

They had reached the chapel. The nuns said a silent mass, the sequence from the age-old Sanctus to the Pater Noster, but Sister Lucia’s thoughts were on more important things than God.

In another month or two, when the police stop looking for me, I’ll be out of this madhouse.

After morning prayers, Sister Lucia marched with the others to the dining room, surreptitiously breaking the rule, as she did every day, by studying their faces. It was her only entertainment. It was incredible to think that none of them knew what the other sisters looked like.

She was fascinated by the faces of the nuns. Some were old, some were young, some pretty, some ugly. She could not understand why they all seemed so happy. There were three faces that Lucia found particularly interesting. One was Sister Teresa, a woman who appeared to be in her sixties. She was far from beautiful, and yet there was a spirituality about her that gave her an almost unearthly loveliness. She seemed always to be smiling inwardly, as though she carried some wonderful secret within herself.

Another nun that Lucia found fascinating was Sister Graciela. She was a stunningly beautiful woman in her early thirties. She had olive skin, exquisite features, and eyes that were luminous black pools.

She could have been a film star, Lucia thought. What’s her story? Why would she bury herself in a place like this?

The third nun who captured Lucia’s interest was Sister Megan. Blue-eyed, blonde eyebrows and lashes. She was in her late twenties and had a fresh, open faced look.

What is she doing here? What are any of these women doing here? They’re locked up behind these walls, given a tiny cell to sleep in, rotten food, eight hours of prayers, hard work and too little sleep. They must be pazzo – all of them.

She was better off than they were, because they were stuck here for the rest of their lives, while she would be out of here in a month or two. Maybe three, Lucia thought. This is a perfect hiding place. I’d be a fool to rush away. In a few months, the police will decide that I’m dead. When I leave here and get my money out of Switzerland, maybe I’ll write a book about this crazy place.

A few days earlier Sister Lucia had been sent by the Reverend Mother to the office to retrieve a paper and while there she had taken the opportunity to start looking through the files. Unfortunately she had been caught in the act of snooping.

‘You will do penance by using the Discipline,’ the Mother Prioress Betina signalled her.

Sister Lucia bowed her head meekly and signalled, ‘Yes, Reverend Mother.’

Lucia returned to her cell, and minutes later the nuns walking through the corridor heard the awful sound of the whip as it whistled through the air and fell again and again. What they could not know was that Sister Lucia was whipping the bed.

These freaks may be into S & M, but not yours truly.

Now they were seated in the refectory, forty nuns at two long tables. The Cistercian diet was strictly vegetarian. Because the body craved meat, it was forbidden. Long before dawn, a cup of tea or coffee and a few ounces of dry bread were served. The principal meal was taken at 11.00 a.m., and consisted of a thin soup, a few vegetables and occasionally a piece of fruit.

We are not here to please our bodies, but to please God.

I wouldn’t feed this breakfast to my cat, Sister Lucia thought. I’ve been here two months, and I’ll bet I’ve lost ten pounds. It’s God’s version of a health farm.

When breakfast was ended, two nuns brought washing-up bowls to each end of the table and set them down. The sisters seated about the table sent their plates to the sister who had the bowl. She washed each plate, dried it on a towel and returned it to its owner. The water got darker and greasier.

And they’re going to live like this for the rest of their lives, Sister Lucia thought disgustedly. Oh, well. I can’t complain. At least it’s better than a life sentence in prison …

She would have given her immortal soul for a cigarette.

Five hundred yards down the road, Colonel Ramon Acoca and two dozen carefully selected men from the GOE, the Grupo de Operaciones Especiales, were preparing to attack the convent.

Chapter Four

Colonel Ramón Acoca had the instincts of a hunter. He loved the chase, but it was the kill that gave him a deep visceral satisfaction. He had once confided to a friend, ‘I have an orgasm when I kill. It doesn’t matter whether it’s a deer or a rabbit or a man – there’s something about taking a life that makes you feel like God.’

Acoca had been in military intelligence, and he had quickly achieved a reputation for being brilliant. He was fearless, ruthless and intelligent, and the combination brought him to the attention of one of General Franco’s aides.

Acoca had joined Franco’s staff as a lieutenant, and in less than three years he had risen to the rank of colonel, an almost unheard-of feat. He was put in charge of the Falangists, the special group used to terrorize those who opposed Franco.

It was during the war that Acoca had been sent for by a member of the OPUS MUNDO.

‘I want you to understand that we’re speaking to you with the permission of General Franco.’

‘Yes, sir.’

‘We’ve been watching you, Colonel. We are pleased with what we see.’

‘Thank you, sir.’

‘From time to time we have certain assignments that are – shall we say – very confidential. And very dangerous.’

‘I understand, sir.’

‘We have many enemies. People who don’t understand the importance of the work we’re doing.’

‘Yes, sir.’

‘Sometimes they interfere with us. We can’t permit that to happen.’

‘No, sir.’

‘I believe we could use a man like you, Colonel. I think we understand each other.’

‘Yes, sir. I’d be honoured to be of service.’

‘We would like you to remain in the army. That will be valuable to us. But from time to time, we will have you assigned to these special projects.’

‘Thank you, sir.’

‘You are never to speak of this.’

‘No, sir.’

The man behind the desk had made Acoca nervous. There was something overpoweringly frightening about him.

In time, Colonel Acoca was called upon to handle half a dozen assignments for the OPUS MUNDO. As he had been told, they were all dangerous. And very confidential.

On one of the missions Acoca had met a lovely young girl from a fine family. Up to then, all of his women had been whores or camp followers, and Acoca had treated them with savage contempt. Some of the women had genuinely fallen in love with him, attracted by his strength. He reserved the worst treatment for them.

But Susana Cerredilla belonged to a different world. Her father was a professor at Madrid University, and Susana’s mother was a lawyer. Susana was seventeen years old, and she had the body of a woman and the angelic face of a Madonna. Ramón Acoca had never met anyone like this woman-child. Her gentle vulnerability brought out in him a tenderness he had not known he was capable of. He fell madly in love with her, and for reasons which neither her parents nor Acoca understood, she fell in love with him.

On their honeymoon, it was as though Acoca had never known another woman. He had known lust, but the combination of love and passion was something he had never previously experienced.

Three months after they were married, Susana informed him that she was pregnant. Acoca was wildly excited. To add to their joy, he was assigned to the beautiful little village of Castilbanca, in the Basque country. It was in the autumn of 1936 when the fighting between the Republicans and Nationalists was at its fiercest.

On a peaceful Sunday morning, Ramón Acoca and his bride were having coffee in the village plaza when the square suddenly filled with Basque demonstrators.

‘I want you to go home,’ Acoca said. ‘There’s going to be trouble.’

‘But you –?’

‘Please. I’ll be all right.’

The demonstrators were beginning to get out of hand.

With relief, Ramón Acoca watched his bride walk away from the crowd towards a convent at the far end of the square. And as she reached it, the door to the convent suddenly swung open and armed Basques who had been hiding inside, swarmed out with blazing guns. Acoca had watched helplessly as his wife went down in a hail of bullets, and it was on that day that he had sworn vengeance on the Basques. The Church had also been responsible.

And now he was in Ávila, outside another convent. This time they’ll die.

Inside the convent, in the dark before dawn, Sister Teresa held the Discipline tightly in her right hand and whipped it hard across her body, feeling the knotted tails slashing into her as she silently recited the Miserere. She almost screamed aloud, but noise was not permitted, and she kept the screams inside her. Forgive me, Jesus, for my sins. Bear witness that I punish myself, as you were punished, and I inflict wounds upon myself, as wounds were inflicted upon you. Let me suffer, as you suffered.

She was near fainting from the pain. Three more times she flagellated herself and then sank, agonized, upon her cot. She had not drawn blood. That was forbidden. Wincing against the agony that each movement brought, Sister Teresa returned the whip to its black case and rested it in a corner. It was always there, a constant reminder that the slightest sin had to be paid for with pain.

Sister Teresa’s transgression had happened that morning as she was rounding the corner of a corridor, eyes down, and bumped into Sister Graciela. Startled, Sister Teresa had looked into Sister Graciela’s face. Sister Teresa had immediately reported her infraction and the Reverend Mother Betina had frowned disapprovingly and made the sign of discipline, moving her right hand three times from shoulder to shoulder, her hand closed as though holding a whip, the tip of her thumb held against the inside of her forefinger.

Lying on her cot that night, Sister Teresa had been unable to get out of her mind the extraordinarily beautiful face of the young girl she had gazed at. Sister Teresa knew that as long as she lived she would never speak to her and would never even look at her again, for the slightest sign of intimacy between nuns was severely punished. In an atmosphere of rigid moral and physical austerity, no relationships of any kind were allowed to develop. If two sisters worked side by side and seemed to enjoy each other’s silent company, the Reverend Mother would immediately have them separated. Nor were the sisters permitted to sit next to the same person at table twice in a row. The church delicately called the attraction of one nun to another ‘a particular friendship’, and the penalty was swift and severe. Sister Teresa had served her punishment for breaking the rule.

Now the tolling bell came to Sister Teresa as though from a great distance. It was the voice of God, reproving her.

In the next cell, the sound of the bell rang through the corridors of Sister Graciela’s dreams, and the pealing of the bell was mingled with the lubricious creak of bedsprings. The Moor was moving towards her, naked, his manhood tumescent, his hands reaching out to grab her. Sister Graciela opened her eyes, instantly awake, her heart pounding frantically. She looked around, terrified, but she was alone in her tiny cell and the only sound was the reassuring tolling of the bell.

Sister Graciela knelt at the side of her cot. Jesus, thank You for delivering me from the past. Thank You for the joy I have in being here in Your light. Let me glory only in the happiness of Your being. Help me, my Beloved, to be true to the call You have given me. Help me to ease the sorrow of Your sacred heart.

Sister Graciela rose and carefully made her bed, then joined the procession of her sisters as they moved silently towards the chapel for Matins. She could smell the familiar scent of burning candles and feel the worn stones beneath her sandalled feet.

In the beginning when Sister Graciela had first entered the convent, she had not understood it when the Mother Prioress had told her that a nun was a woman who gave up everything in order to possess everything. Sister Graciela had been fourteen years old then. Now, seventeen years later, it was clear to her. In contemplation she possessed everything, for contemplation was the mind replying to the soul, the waters of Siloh that flowed in silence. Her days were filled with a wonderful peace.

Thank You for letting me forget the terrible past, Father. Thank You for standing beside me. I couldn’t face my terrible past without you … Thank You … Thank You …

When Matins were over, the nuns returned to their cells to sleep until Lauds, the rising of the sun.

Outside, Colonel Ramón Acoca and his men moved swiftly in the darkness. When they reached the convent, Colonel Acoca said, ‘Jaime Miró and his men will be armed. Take no chances. He looked at the front of the convent, and for an instant, he saw that other convent with Basque partisans rushing out of it, and Susana going down in a hail of bullets.

‘Don’t bother taking Jaime Miró alive,’ he said.

Sister Megan was awakened by the silence. It was a different silence, a moving silence, a hurried rush of air, a whisper of bodies. There were sounds she had never heard in her fifteen years in the convent. She was suddenly filled with a premonition that something was terribly wrong.

She rose quietly in the darkness and opened the door to her cell. Unbelievably, the long stone corridor was filled with men. A giant with a scarred face was coming out of the Reverend Mother’s cell, pulling her by the arm. Megan stared in shock. I’m having a nightmare, Megan thought. These men can’t be here.

‘Where are you hiding him?’ Colonel Acoca demanded.

The Reverend Mother Betina had a look of stunned horror on her face. ‘Ssh! This is God’s temple. You are desecrating it.’ Her voice was trembling. ‘You must leave at once.’

The Colonel’s grip tightened on her arm and he shook her. ‘I want Miró, Sister.’

The nightmare was real.

Other cell doors were beginning to open, and nuns were appearing, looks of total confusion on their faces. There had never been anything in their experience to prepare them for this extraordinary happening.

Colonel Acoca pushed Sister Betina away and turned to Patricio Arrieta, one of his lieutenants. ‘Search the place. Top to bottom.’

Acoca’s men began to spread out, invading the chapel, the refectory and the cells, waking those nuns who were still asleep, and forcing them roughly to their feet through the corridors and into the chapel. The nuns obeyed wordlessly, keeping even now their vows of silence. To Megan the scene was like a film with the sound turned off.

Acoca’s men were filled with a sense of vengeance. They were all Falangists, and they remembered only too well how the Church had turned against them during the Civil War and supported the Loyalists against their beloved leader, Generalissimo Franco. This was their chance to get their own back. The nuns’ strength and silence made the men more furious than ever.

As Acoca passed one of the cells, a scream echoed from it. Acoca looked in and saw one of his men ripping the habit from a nun. Acoca moved on.

Sister Lucia was awakened by the sounds of men’s voices yelling. She sat up in a panic. The police have found me, was her first thought. I’ve got to get out of here. There was no way out of the convent except through the front door.

She hurriedly rose and peered out into the corridor. The sight that met her eyes was astonishing. The corridor was filled not with policemen, but with men in civilian clothes, carrying weapons, smashing lamps and tables. There was confusion everywhere as they raced around.

The Reverend Mother Betina was standing in the centre of the chaos, praying silently, watching them desecrate her beloved convent. Sister Megan moved to her side, and Lucia joined them.

‘What the h – what’s happening? Who are they?’ Lucia asked. They were the first words she had spoken aloud since entering the convent.

The Reverend Mother put her right hand under her left armpit three times, the sign for hide.

Lucia stared at her unbelievingly. ‘You can talk now. Let’s get out of here, for Christ’s sake. And I mean for Christ’s sake.’

Patricio Arrieta, the Colonel’s key aide, hurried up to Acoca. ‘We’ve searched everywhere, Colonel. There’s no sign of Jaime Miró or his men.’

‘Search again,’ Acoca said stubbornly.

It was then that the Reverend Mother remembered the one treasure that the convent had. She hurried over to Sister Teresa and whispered, ‘I have a task for you. Remove the gold cross from the chapel and take it to the convent at Mendavia. You must get it away from here. Hurry!’

Sister Teresa was shaking so hard that her wimple fluttered in waves. She stared at the Reverend Mother, paralyzed. Sister Teresa had spent the last thirty years of her life in the convent. The thought of leaving it was beyond imagining. She raised her hand and signed, I can’t.

The Reverend Mother was frantic. ‘The cross must not fall into the hands of these men of Satan. Now do this for Jesus.’

A light came into Sister Teresa’s eyes. She stood very tall. She signed, for Jesus. She turned and hurried towards the chapel.

Sister Graciela approached the group, staring in wonder at the wild confusion around her.

The men were getting more and more violent, smashing everything in sight. Colonal Acoca watched them, approvingly.

Lucia turned to Megan and Graciela. ‘I don’t know about you two, but I’m getting out of here. Are you coming?’

Ücretsiz ön izlemeyi tamamladınız.